Полная версия

Hollow Places

Across the country, and especially in the south, large numbers of agricultural labourers had been turned into paupers by a system that saw the rate-payers, who were also their employers, agree to pay or subsidise their wages through the poor rate. The money they took home each week was linked to the size of their family and the price of a loaf of bread. There were many variations to this system. In some villages, labourers were auctioned weekly to the highest bidders. One Nathan Driver explained to the Select Committee on the Poor Laws how things worked in Furneux Pelham. There were some ninety agricultural labourers in a parish of 2,500 acres, which according to Mr Driver meant there were eighteen labourers too many. The solution was to put the names of all ninety labourers in a hat and share them out between the farms in Furneux Pelham – according to their size – on a daily basis. The farmers would then have to find something for them to do – chopping down a tree, for example.

Twenty-five children were born in the Pelhams in 1834, to a thatcher, a shoemaker, two yeoman farmers and twenty-one agricultural labourers. At the beginning of the 1830s, 62 per cent of men over twenty in the three Pelhams were agricultural labourers, a little higher than the Hertfordshire average and nearly three times the national one. By then considerably more families earned their living in England from trade, manufacturing or handicrafts, than worked on the land, but still agricultural labourers made up the single largest occupation group – some 745,000 of them. Most of us have more agricultural labourers in our family tree than any other ancestors. ‘Agricultural labourer’ does not necessarily tell the whole story. In the column marked ‘Occupation’ on the 1841 Census, the enumerators would have written the diminutive ‘Ag Lab’ ad nauseam, so it is disappointing that they didn’t relieve the boredom by being more precise. Where were the ploughmen, the carters, the hedgers, the headmen, the woodcutters and the common taskers? It has been said that there were hierarchies among farm workers as intricate as that among the gentility.

It is impossible to consider this period without turning to the campaigning journalist and chronicler of the pains and pleasures of rural life William Cobbett. On one of his ‘rural rides’ around England in the 1820s he encountered a group of women labourers in ‘such an assemblage of rags as I never before saw’. And of labourers near Cricklade: ‘Their dwellings are little better than pig-beds and their looks indicate that their food is not nearly equal to that of a pig. Their wretched hovels are stuck upon little bits of ground on the road side … It seems as if they had been swept off the fields by a hurricane, and had dropped and found shelter under the banks on the road side! Yesterday morning was a sharp frost; and this had set the poor creatures to digging up their little plats of potatoes. In my whole life I never saw human wretchedness equal to this; no, not even amongst the free negroes in America.’

Accommodation for these people was notoriously bad: ‘The majority of the cottages that exist in rural parishes,’ wrote the Reverend James Fraser in the late 1860s, ‘are deficient in almost every requisite that should constitute a home for a Christian family in a civilized community.’

Labourers in the Pelhams were probably not living on roots and sorrel, nor had they – in the words of Lord Carnarvon – been reduced to a plight more abject than that of any race in Europe. Housing may also have been better than mud and straw hovels found elsewhere. Over forty new houses were built in the first thirty years of the nineteenth century, which might suggest a benevolent land-owning class, but the population of the villages increased as well, so the ratio of families to houses barely changed. In the early 1830s, some 228 families shared 177 homes.

The Reverend Fraser disapproved of such cramped conditions, adding that, ‘it is impossible to exaggerate the ill effects of such a state of things in every aspect – physical, social, economical, moral, intellectual’. What did such an existence do to their minds? Did it make them more or less likely to see holes and think of dragons?

Reading contemporary accounts of agricultural labourers, we are told that they are not just ill-paid and ill-fed and ill-clothed but also unimaginative, ill-educated, ignorant, illogical and brutish. ‘They seem scarcely to know any other enjoyments than such as is common to them, and to the brute beasts which have no understanding … So very far are they below their fellow men in mental culture,’ wrote John Eddowes in his 1854 The Agricultural Labourer as He Really Is. This is the cruel stereotype that christened every Ag Lab ‘Hodge’ and gave him an awkward gait, ungainly manners, a slow wit and an indecipherable patois. Another observer described the limited horizons of such a labourer: ‘Like so many of his friends, he had never been out of a ten-mile radius; he had never even climbed to the top of yonder great round hill.’ And there were said to be rustics who lived within ten miles of the sea but had never seen it. They were ‘intellectual cataleptics’, interested only in food and shelter, according to one mid-century journalist.

In one of his characteristically oblique and brilliant studies, the historian Keith Snell set out to uncover whether this really was all that the labourer wanted by scouring letters home from emigrants. Several themes stood out. They valued their families, wanted to be free from the overseer of the poor, craved secure work and better treatment by those offering it, and they demonstrated a marked interest in their environment – in the land and the livestock.

This only tells us about those who could write, but it gets around the famous reticence of the labourer, the mysterious barrier of ‘Ay, ay’, ‘may be’, ‘likely enough’ that greeted any enquiry, and contemporary observers attributed to stupidity.

Labourers were not alone, their employers were not celebrated for their conversational skills: In his Professional Excursions around Hertfordshire published in 1843, the auctioneer Wolley Simpson gives a wonderful description of a farmer which reads like the children’s game where you have to avoid saying ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Q. The Land you hold of the Marquis, is very good is it not Mr. Thornton?

A. It ai’nt bad Sir.

Q. The Timber I understand in this neigh-bourhood is very thriving.

A. Why I’ve seen worse Sir.

Q. You have an abundance of chalk too which is an advantage?

A. We don’t object to it Sir.

Q. You are likewise conveniently situated for markets?

A. Why we don’t complain Sir.

Q. You are plentifully supplied with fruit if I may judge from your Orchards?

A. Pretty middling for that Sir.

Q. Corn is at a fair price now for you?

A. It be’nt a bit too high Sir.

Q. The Canals must facilitate the convey-ance of produce considerably?

A. They are better than bad roads to be sure Sir.

And so on in the same vein. Simpson concludes that ‘evasion had become habitual, and I believe it to be a principle in rural education’.

Did village schools teach anything else besides?

The traditional way to measure literacy is to count the number of people who could sign their name on marriage licences and other documents. Although the method has its detractors, it is still a useful ready reckoner. In 1834, two marriages in the Pelhams involved agricultural labourers. All made their mark, with the exception of one witness, sixty-five-year-old Mary Bayford. This is not surprising as not all their employers could write: in the previous year the farmer and Vestry (local council) member John Hardy made his mark in the Overseers accounts.

There had been a charity school in Furneux Pelham since 1756 thanks to a bequest by the widow of the Reverend Charles Wheatly to provide a proper master to teach eight poor boys and girls to read and write. In an 1816 report to the parliamentary Select Committee somebody observed of the Pelhams: ‘The poor have not sufficient means of education; but the minister concludes they must be desirous of possessing them.’ By 1833, there was a schoolmaster and mistress looking after twenty-one boys and girls, but even with the existence of a school and the growing attendance figures, there were no guarantees that children would turn up regularly. In January 1854, the Hertfordshire school inspector wrote: ‘In country parishes boys are employed from three to five months in the year after the age of seven, and they are withdrawn from school altogether between ten and eleven. I believe that at present there are scarcely any children of agricultural labourers above that age in regular attendance at schools in my district.’

While the gentry endowed and managed the schools, their tenant farmers were less than enthusiastic, insisting that workers brought their children to the fields with them. Many, if not most, parents could not afford to forfeit the extra pennies the children would bring home. A survey of over 500 labouring families in East Anglia in the 1830s found that only about half the income of an average family came from the husband’s day-work. Nearly 80,000 children were permanently employed as agricultural labourers in the middle of the century. At least 5,500 of these were between the ages of five and nine. At harvest time classrooms would be empty.

They could be kept off at short notice for reasons that would baffle us, writes Pamela Horn: ‘Sometimes a strong wind would loose branches and twigs, and children would be kept from school to collect this additional winter firing.’ In the winter months, hard-pressed parents needed their children to earn extra money picking stones, rat-catching or beating for the squire’s shooting parties. These jobs not only kept them from the classroom, they provided them with little alternative stimulation. Common occupations such as bird scaring were an isolating and literally mind-numbing activity. Children would be on their own from dawn to dusk, because it was thought they wouldn’t work as hard if they had someone to talk to; as one chronicler of rural life in Norfolk observed, farmers thought that ‘One boy is a boy, two boys is half a boy, and three boys is no boys at all.’

If children did get past the classroom door, what did the schools teach them? The gentry might have been eager to do their duty and help provide an education to the agricultural workers, but their idea of what constituted that education was not ours. Needlework, cleaning and the catechism were often the extent of it. In the 1840s, girls were taught such rigorous academic subjects as the ‘art of getting up linen’ – but only as a reward if they showed good conduct and industry.

At the first school inspection of Furneux Pelham, in February 1845, seventy-one children turned up for the examination. There were nearly three times as many girls as boys, and just over half were older than ten. Twenty-four were, ‘Able to read a Verse in the Gospels without blundering’, twenty-six girls were ‘Working sums in the Simple Rules’, but only two boys; not one child had advanced to ‘Sums in the Compound Rules’ or the even loftier ‘Working Sums in Proportion and the Higher Rules’.

One school inspector a few years later lamented that children’s copy books rendered a dull study duller: ‘For of what use can it be to copy ten and twelve times over such crackjaw words as these: “Zumiologist”, “Xenodochium” …? Or such pompous moral phrases as “Study universal rectitude”?’

Pamela Horn gives examples of long-winded sums from the period designed perhaps to keep children occupied: ‘What will the thatching of the following stacks cost at 10 d. per square foot, the first was 36 feet by 27, the second 42 by 34, the third 38 by 24, and the fourth 47 by 39?’ The Hertfordshire diarist John Carrington set his son similar problems that might have proved useful to old Master Lawrence: ‘I desire to know how much timber there is in 24-foot long and 24-inches girt.’ Beneath the sum Carrington observed that a six-hundred-year-old oak fell down in Oxford in June 1789, ‘the girt of the oak was 21 feet 9 inches, height 71 feet 8 inches. Cubic contents 754 feet … luckily did no damage.’ Perhaps a functional education at least.

This is a picture of sorts, of the men who went to fell that tree, of their education – or lack of – their cares and their material circumstances. It does not get us very much closer to understanding why they thought they had found a dragon’s lair. Perhaps I am going about this back to front because the best way to get at the mental life of a nineteenth-century rural labourer is to take at face value the stories they told. The cultural historian Robert Darnton writes in his essay ‘Peasants Tell Tales’, that folk tales are one of the few points of entry into the mental world of peasants in the past, and the recurring motifs in early tales can shed light on the preoccupations of the people who told them – such as the tensions caused by the lack of food for all the family members and the preponderance of step-mothers with children of their own, in a world where it was fairly commonplace to lose a partner to illness or childbirth. While I have been asking what the life and education of an Ag Lab can tell us about the story, I might better have asked what the story can tell us about the life of an Ag Lab. They believed that dragons once lived in holes beneath yew trees. That may well be the most interesting thing we will ever know about them.

A postscript: I like to think that whatever happened that morning coloured the life of Thomas Skinner, that his encounter as a child with Piers Shonks and dragon’s holes gifted him a curious mind and a life in search of other hollow places. Writing in 1926, a local historian in Anstey recalled in passing an old Gentleman Skinner who had found the entrance to the Blind Fiddler’s tunnel and who ‘took the greatest interest in antiquarian researches’.

9

To break a branch was deemed a sin,

A bad-luck job for neighbours,

For fire, sickness, or the like

Would mar their honest labours.

—from a ballad written after the illicit felling of a tree in 1824

Master Lawrence and the others were walking into a story when they stepped out of their doors that still winter morning. Imagine the carpenter’s yard as a tree’s graveyard, boards and off-cuts and shavings of timber memorialising particular oaks or elms taken from woodland and hedgerows. Imagine gates and window frames that Lawrence remembered as branches, and entire cruck-frames that had once grown in Hormead Park Wood. ‘The quality of a tree was remembered to the last fragment after the bulk of the log had been used,’ wrote Walter Rose in The Village Carpenter. ‘In any carpenter’s yard there are piles of oddments – small pieces left over from many trees – but though they are all mixed up, it is usually remembered from which tree each piece was cut.’

Soon there would be loppings of a yew in Lawrence’s yard.

At that hour, women would be fetching water in buckets hanging from yokes, carters were securing the traces to horses while young boys baited them. Old timers might already be warming themselves at the furnace in James Funston’s Smithy. A man could speak freely there without being held to his word.

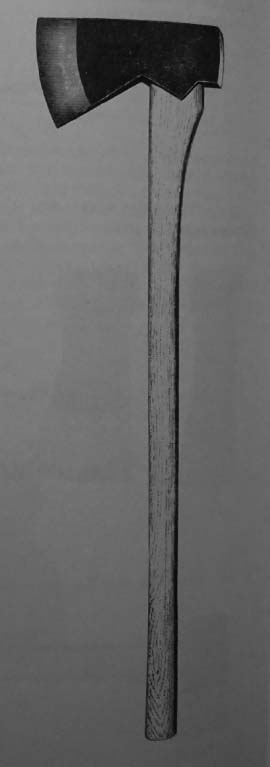

The track to the tree led south, following the boundary between Church Hill Field and Broadley Shot. Small children with chilblains hobble along in hard boots – off to pick flints or clean turnips. From the northern edge of Chalky Field it was little more than half a mile south and then west to Patricks Wood, and beyond the hornbeams lay Great and Little Pepsells where the labourers could set down their stoneware jars and their shovels and axes.

The spot was oddly remote. It is the landscape of M. R. James’s ghost story ‘A Neighbour’s Landmark’ that is one minute picturesque, the next, with the changing of the light, bleak, frightening and vulnerable to supernature. Imagine this spot on a grey winter’s morning setting your axe to a village landmark and the only building in view is the tower of the church within whose walls an ancient legend sleeps. Marked by a small triangle where three fields meet, hemmed by three parish boundaries and two dark blocks of woodland, it was the kind of place where gallows once stood, or gibbets swung – places where suicides and strangers were buried. Yews are known to have been used as hanging trees. Such knowledge might well have worked upon the minds of those men that morning. W. B. Gerish is good on this, writing of an older time, of the medieval winter when ‘The spirit world was abroad, riding in every gale, hiding in the early and late darkness of evening among the shadows of the farmhouse, of the rickyard, of the misty meadows, of the dark-some wood. Ghosts – we talk about ghosts, but our ancestors lived with them from All Hallows to Candlemas.’

R. M. Healey in his Shell Guide to Hertfordshire is generous about the countryside thereabouts, finding in it Samuel Palmer’s elegiac landscape paintings, better Palmer’s dark etchings from his final years after he had grown angry at the plight of the agricultural labourer.

In the right weather, the wrong weather, the view belongs in the old nurse’s tale that troubled Jane Eyre’s imagination, making her think of Thomas Bewick’s engraving of a ‘black horned thing seated aloof on a rock, surveying a distant crowd surrounding a gallows’. But so would many such views in England: the historian John Lowerson has written about the ‘popular sense of an eternal cosmic battle between good and evil that is being fought out in an essentially rural English context’. Our yew site is a place as good as any for such battles, for stories, for putting ideas in men’s heads about dragons and their slayers. Was it the place as much as the belief that a dragon once stalked those parts that would soon make them think they’d found a dragon’s lair?

Farm labourers worked from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the winter. Six shillings a week was a usual wage, but felling timber was paid by the load: one shilling for fifty cubic feet. You can do the working out. John Carrington’s oak we met in the last chapter would have earned them fifteen shillings. Was it blood money enough? Were they superstitious about their task that day? No doubt there were those who thought that chopping down a yew brought bad luck. Plant lore is thick with injunctions against bringing down trees. The folklorist Jeremy Harte, writing about the Isle of Man, tells of the seemingly lonely places where ‘locals know about the elder trees that should never be touched, not since the farmer hacked them back, and hanged himself in the barn that night’. But Harte is writing about fairies, and it is thorn trees and elders, not yews, that must be left alone. But a yew was also a sacred tree to many: ‘A bed in hell is prepared for him / Who cut the tree about thine ears.’ Did the men have sentiments similar to this final couplet from an old rhyme about the Yew Tree Well in Easter Ross, Scotland? A chill warning to those wielding an axe. The Yew of Ross in Ireland had to be prayed down by St Laserian because its wood was wanted, but no one dared fell it. Recall King Hywel Dda’s tenth-century prohibition on felling yews associated with saints. Do similar injunctions survive far and wide in the collective memory? When the Victorian archaeologist Augustus Pitt-Rivers removed an old yew from a prehistoric burial mound in Dorset, the locals were not happy, even though Pitt-Rivers said the tree was dead: ‘I afterwards learned that the people of the neighbourhood attached some interest to it, and it has since been replaced.’

John Aubrey relates the fate of the men who felled an oak in 1657 and in passing recalls the wife and son of an earl who died after he had an oak grove removed. These tales linger and still give pause for thought today to the sensitive and cautious: Harte writes, ‘When we find that the N18 from Limerick to Ennis curves to go around a fairy thorn, we admire the knowledge of Eddie Lenihan, who campaigned to save the tree, as well as the prudence of the County Surveyor who knew of the risk involved in damaging it.’

Still, the Lawrences and the Skinners had their work to do, and so they savaged the roots of the great tree. Specifically the roots, I think. There is an engraving by Turner in his Liber Studiorum called ‘Hedging and Ditching’. Two men are in a ditch in the ground fetching down a tree, not neatly chopping it down, but seeming to lever it out of the ground with pickaxes. A woman in a bonnet with a shawl over her shoulder walks by looking on. This is no rural idyll. The drawing has something in common with First World War art, with the pencil lines that suggest mud and stones, the thin leafless trees in the hedge, shredded of the fullness of trees. Grubbing up is an evocative expression. It is an unpleasant image, total and annihilating: trees torn violently from the soil. I think of Ted Hughes’ Whale-Wort torn out by the roots and flung into the sea when he just wanted to sleep. It is the slow deliberate painstaking act of men with hand tools. Those in Turner’s sketch might be doing hard labour; they look a bad lot, like pirates or smugglers – Turner was on the coast at East Sussex, so maybe they were.

Forget a neat V-shaped wedge incised with an axe prior to sawing. Dynamite and perhaps club hammers would make more sense than a copybook felling. An ancient yew with its hollows and split trunks and the irregular sprawl of its weary branches mocks the surgical approach. H. Rider Haggard, the author of the adventure stories She and King Solomon’s Mines, gives the best and most plausible description of how the tree was felled in his A Farmer’s Year: Being His Commonplace Book for 1898. He writes that there are two ways of felling a tree:

one the careless and slovenly chopping off of the tree above the level of the ground, the other its scientific ‘rooting’. In rooting at timber, the soil is first removed from about the foot of the bole with any suitable instrument till the great roots are discovered branching this way and that. Then the woodsmen begin upon these with their mattocks, which sink with a dull thud into the soft and sappy fibre.

This was known as grub-felling in East Anglia and was the common method for bringing down timber trees in that part of the country.

By Wigram’s account, Lawrence and the other men had an uncommon amount of trouble with those roots. Perhaps their hearts were not in it, or something held back the full strength of their axe strokes. Did one of them stroke the scaly bark that yews can slough off to get rid of infections? Did it rattle under their fingers and the sap begin to run blood red? Fred Hageneder in his Yew: A History tells us that the yew is the only European tree that can bleed red sap. A feat that is scientifically unexplained, he says. The yew at Nevern in Wales is notorious for bleeding the blood of those buried in its churchyard. A bleeding tree might have given those men – any men – second thoughts. Or did the texture of its bark look like scales from a picture book dragon? In Ulverton, his extraordinary record of a fictional village across time, Adam Thorpe channels an old carpenter in an inn in 1803 regaling a visitor with his memories. He recalls the time the master carpenter chose an oak by smell, seasoned it for two years, then made a lid for the church font. ‘Atween you an’ I, though, I can spot a dragon in them patterns. I reckons as how there were a dragon in that tree. He’ll avenge hisself one day.’ Is this a brilliant bit of invention or does Thorpe know of a folk tradition among carpenters about dragons in trees?