Полная версия

Hollow Places

There were not hundreds of soldiers, gentry and nobility, but over ten thousand. Their clothes were so fine that one French eyewitness said noblemen were walking around with their estates on their back because they had mortgaged their lands to finance the cloth. The temporary palace contained five thousand square feet of the finest glass ever made. A fountain ran with claret, but if you preferred beer, the English had brought 14,000 gallons with them – presumably to wash down their other rations: 9,000 plaice, 8,000 whiting, 4,000 sole, 3,000 crayfish, 700 conger eels, 300 oxen, 2,000 chickens, 1,200 capons, 2,000 sheep and over 300 heron. As Melvyn Bragg said when his BBC Radio 4 programme In Our Time tackled the occasion, ‘The fun is in the detail.’ And that great dragon in the sky stands for the detail that the picture, for all its intricacy, can only hint at.

Encountering that print during my quest for Great Pepsells was serendipitous: with its associations, its mysteries, its vivid historical detail, its poetic licence, its riddles, its unwitting challenge to find out just how much history it contained, and, of course, its dragons.

7

It is not down in any map; true places never are.

—Herman Melville, Moby Dick, 1851

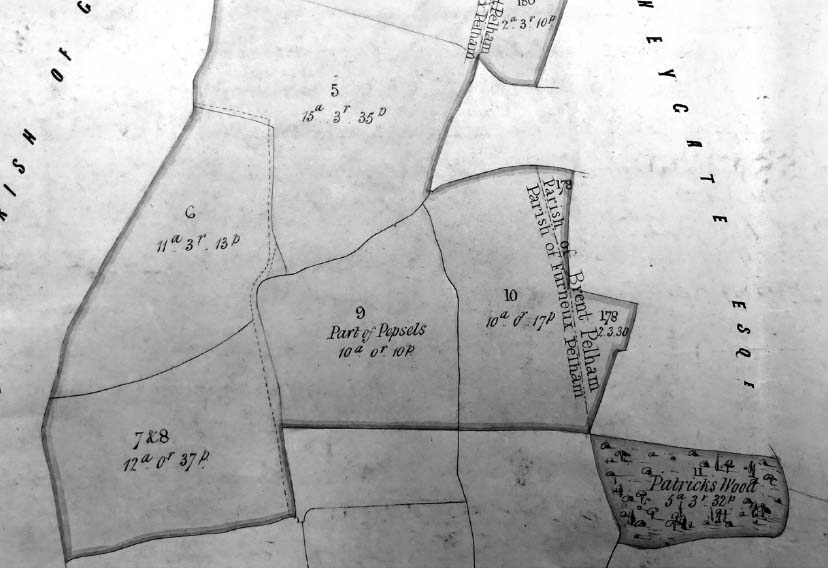

Ancient yews stand few and far between. Did one really straddle the boundary of Great and Little Pepsells until the early nineteenth century? A four-foot by three-foot oblong of greying parchment lies unfolded on the chart table at the Hertfordshire Archives, held flat by weighted leather snakes to reveal a jigsaw puzzle of Furneux Pelham’s fields. The 1836 Act of Parliament that did away with tithes had the wonderful side effect of creating remarkable encyclopedic maps and surveys, covering some 80 per cent of English parishes. Every field within the parish bounds is there, numbered and surveyed at six chains, or 132 yards, to every inch, some enclosed shortly before the map was made, neat and geometrical, others with edges softened by time and use, squashed polygons, their boundaries meandering and dog-legged to attest to their antiquity. The odd large field bears a dotted line intersected by S-marks to tie fields together that were not then enclosed, but considered separate. Thin yellow roads run east to west and north to south partitioning the village. Along them, in two or three places, buildings cluster in plan: red for homes and grey for all the others, the church indicated by a cross, the windmill a small crude X on a stick. There are avenues of trees, blocks of woodland, ponds and the River Ash roughly bisecting the map.

It was surveyed a hundred years before Miss Prior’s school map, and whereas her students had found some 300 field names, the tithe maps for Brent and Furneux Pelham list over 400. Some names had swapped fields over time: Handpost Field is on the other side of the road – perhaps the handpost moved, or more likely the children or the surveyors made a mistake. Many changed their names, becoming more poetic, like Moat Duffers, which was originally Dove House Field, or less so, like Violets Meadow, which was once the much lovelier Fylets. The field identified as Great Pepsells by Ted Barclay, but St Patricks Hill by the school map, is five separate fields on the tithe: ancient enclosures amalgamated by Victorian landowners. On the western boundary, no. 7 is simply Spring, and no. 8 the self-explanatory eleven-acre field called Ten Acres. On the eastern edge is no. 10 Wood Field, and part of no. 12, the delightful Lady Pightle. There, in the middle, is no. 9, Pepsels and directly to the north is field no. 5, known then as Pipsels Mead.

Strikingly, a track is marked on the tithe map crossing the intersection of Pepsels, Nether Rackets, Pipsels Mead and Ten Acres fields. This track might have passed straight through the stile in the yew tree. The track – a tunnel of dashed lines on the map – goes no further, as if it led to something no longer there. The countryside is marked with these strange paths to nowhere, or rather paths to the past.

The good Reverend Wigram had not made up the names of Great and Little Pepsells after all, so perhaps no one had invented the tree either. The boundary between them was a real place and you could visit it still. There may even be something in the rest of the tale, if once again we allow the logic of that rustic who would not have believed a word of Shonks’ tale if he hadn’t seen the place in the wall with his own eyes. There was certainly a field, so we might as well believe that there was a tree, but what was an ancient yew of all trees doing growing there astride a track in the middle of nowhere?

A single yew alone outside a churchyard is a great rarity – with or without a dragon’s lair. Of the 311 ancient yews known in Britain, very few are not – and have never been – associated with a known church or religious site, and an ancient yew growing anywhere at all is an unfamiliar sight in the countryside around the Pelhams: there are none in Cambridgeshire, Essex or Bedfordshire, and just two surviving ancient yews known in Hertfordshire – both in churchyards. There are a further seven veteran yews in the county – that is trees between 500 and 1,200 years old according to the latest classification by the Ancient Yew Group – but they are all linked to a church.

The nearest non-churchyard yew is a lone veteran growing in Hatfield Forest some sixteen miles away. Although Oliver Rackham insisted that it was only 230 years old, ‘and should be remembered by anyone who supposes that big yews must always be of fabulous age’. Recent analysis by an arborist suggests that the tree is much older and has a smaller circumference than you’d expect because it has spent much of its life in the shade. Perched on the edge of the decoy lake, sloughing off the bark of its many-corded bole, it conceals the mysterious cavities of ancient yew. Its existence gives us some confidence that our yew is within the geographical distribution of these curious trees.

Nearer to the Pelhams, a remarkable specimen lingers in the churchyard of St James the Great, in Thorley, near Bishop’s Stortford. Ringed by precarious gravestones, the main trunk appears to be made from many closely packed smaller trunks, like the product of black fairy magic, an impenetrable palisade of thick stakes imprisoning some secret. A terrible secret: the tree has been hollowed out by arson, its innards gone, and what remains is dreadfully tormented and charcoaled. Yet still it lives and grows and puts out new leaves. Yews are extraordinary trees. In the church is a certificate, from when the Conservation Foundation ran its Yew Tree Campaign in the 1980s, attesting that the tree is 1,000 years old. Ancient yews are now defined as those over 800 years old, with no upper age limit, but determining the age of yews is about as controversial as botany gets. Tim Hills of the Ancient Yew Group writes that the science has moved on a lot since those certificates were awarded based on the ideas of Allen Meredith in his influential The Sacred Yew. Regardless of its age, the yew at Thorley is rightly something to be revered.

Robert Blair in his eighteenth-century poem ‘The Grave’ calls the yew a cheerless, unsocial plant that loves to spend its time in the midst of skulls and coffins. Illustrating the poem, William Blake depicted the tree’s only merriment as ghosts and shades performing their mystic dance around the trunk under a wan moon, but in his watercolour the tree is at the centre, it is evergreen and blue, not dull, but bright in contrast to the pale spectres encircling it; a tree, like the burned-out Thorley yew, that defies death.

There are many theories as to why yews are found in churchyards, ranging from the prosaic (useful shelter from the storm) to the poetic (yews were symbolic of the journey to the underworld). The church guidebook to St James the Great lists other reasons: as a symbol of immortality, to stop villagers allowing their cattle to stray into the graveyard (its leaves are poisonous), or because Edward I decreed that yews be planted to protect churches from storms. Wherever they grow, it is generally assumed that their siting has some significance, if only because they must have been preserved from the needs of longbow production for some special reason (by the late sixteenth century, Europe had been almost completely denuded of yew wood). Although others have argued that they were planted in churchyards precisely because they were needed for longbow production and they would be protected from livestock. John Brand, the eighteenth-century compiler of superstitions thought this was nonsense, approving instead of Sir Thomas Browne’s conjecture ‘that the planting of yew trees, in Churchyards, seems to derive its origin from the ancient funeral rites, in which, from its perpetual verdure, it was used as an emblem of the resurrection’. Yews are not accidental trees, they mark things, they remember things: wells or springs, boundaries, lost settlements, meeting places, pagan religious sites or perhaps even the burial places of people who dropped dead along a pilgrimage route. What did the Pelham tree mark on its lonely boundary between two fields?

Was it originally planted to mark the site of an early Christian saint’s cells? In about 940 the Welsh King Hywel Dda threatened a fine of sixty sheep for felling yews associated with saints. Or did people gather around the yew long ago? Surviving lone trees may have been moot trees – meeting trees – like the Ankerwycke Yew at Runnymede where King John might have signed Magna Carta, and Henry VIII was said to have met Anne Boleyn for the first time. From Anglo-Saxon times until the modern period many southern and Midlands counties were divided into Hundreds, which took their names from the original moots or meeting places of the Hundred Court. Such places were often marked by a significant tree or stone. The Pelhams were in the Edwinstree Hundred – literally Edwin’s Tree – and early records indicate that the meeting place was somewhere in the Pelhams. Place-name historians have guessed that Meeting Field housed the tree, although that name appears for the first time in the late nineteenth century. Great Pepsells was much closer to the centre of the Hundred, bounded by three parishes and fed by ancient paths and trackways. Was Edwin’s Tree a venerable old yew? One early medieval source links Edwin’s Tree to woodland, and woodland may hide the reason for a lone Hertfordshire yew and that track to nowhere.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, villagers across Essex and Hertfordshire were warned not to be startled by strange lights on the horizon. The engineers of the Ordnance Survey were at large, hauling Ramsden’s immense horse-drawn theodolite from village to village, along with their 100-foot steel chains, twenty-foot high white flags, and their brand-new draught-proof white lights. This was the earliest of the surveys made some eighty years before the large-scale 25-inch with its individual trees. The maps would be plotted at just 1 inch to the mile, but it was a revolution in cartography.

There are remarkable preliminary pencil drawings, made at a larger scale than the published sheets. The fields seem to stand out from the paper in relief, like anatomical specimens in cross section, finely hachured to look more like a coral reef than rural Hertfordshire. Zoom in and the map covering Great Pepsells is heavily shadowed as if seen through storm clouds, the gathering clouds of the Peninsular War perhaps, which hurried the surveyor’s hand. The field boundaries, which would disappear from the published version, are clearly drawn in, and the house and settlements picked out brightly in red ink. Right in the centre of the drawing between the little red dots labelled Johns Pelham and Lily End is Hormead Park Wood, the woodland that adjoins the south-west corner of Great Pepsells. But it is much larger on the 1 inch than it is today. Instead of the tidy rectangle of later maps, the wood meanders across the fields of Furneux Pelham drawing a shape far more typical of an original ancient woodland boundary.

But were these early small-scale maps accurate? They were surveyed in two parts. First the large-scale trigonometry was completed, and then a second survey filled in the resulting triangles with fields and roads, rivers and hills: this was the interior or topographical survey. Map historians write that the very first OS sheets of Kent had been plotted at the end of the eighteenth century to the exacting standards of the pioneering military map-maker William Roy, who insisted that ‘The boundaries of forests, woods, heaths, commons or morasses, are to be distinctly surveyed, and in the enclosed part of the country at the hedge, and other boundaries of fields are to be carefully laid down.’ It was a slow and expensive process, so when they came to do Essex, the chief surveyors were told to make it faster and cheaper, but in the end they only sacrificed the exact shape of fields. So while the 1804 sheets might not be as detailed as the later large-scale maps, it was a proper military survey, and the towns, villages, rivers and hills were plotted accurately. As were the woods, because they could provide cover for ambushes – a French invasion was still feared when the surveyors were at work.

Assured of the map’s accuracy, I laid a copy over later maps, and found that where a finger of the wood points to its northernmost edge, it precisely matches the shape of the boundary between Great and Little Pepsells. (I use italics in an effort to convey the excitement I felt at this discovery. It was as if I had unearthed a fragment of an ancient cuneiform clay tablet and found it joined up perfectly with another found years before to reveal the location of Noah’s ark.) Was it an echo of the northernmost tree-line of Great Hormead Park Wood? Did an ancient yew tree once mark this boundary? Yews, as well as other trees, had been used as meres or boundary markers since Anglo-Saxon times. And there was that telltale path that the yew had straddled, hence the stile in its split trunk, a path terminating at a tree that is no longer there.

There is a later map, one of the last private county maps made before the OS swept all before it: Mr Bryant’s 1822 map reveals that sometime between then and the start of the century, the section of Hormead Park projecting into Furneux Pelham was grubbed up, or, in the terms of the Lord of the Manor’s tenancy agreement for the land, the timber was felled, cut down, stocked up, peeled, hewn, sawn, worked out, made up and carried away. Why was the Yew left untouched?

The same military zeal that saw the birth of the Ordnance Survey saw the felling of thousands of trees not for timber for ships or for the war effort as is sometimes said, but simply because corn prices went through the roof. The militaristic language used to describe the campaigns against Napoleon were used to describe the agricultural revolution against the inefficient use of land. ‘Let us not be satisfied with the liberation of Egypt or the subjugation of Malta,’ wrote the first President of the Board of Agriculture, in 1803. ‘Let us subdue Finchley Common; let us conquer Hounslow Heath, let us compel Epping Forest to submit to the yoke of improvement.’

The transformation of the ancient clay or heavy-lands of Eastern England from medieval bullock fattening into intensive arable is now recognised as one of the key stages of the agricultural revolution. Arable land in the Pelhams increased by 130 acres in the half-century after 1784, but pasture fell by only three. It was woodland and hedgerow that gave way to the plough. Hertfordshire was one of the counties with the least waste – or uncultivated land – as so much of it had already been enclosed and cultivated in the Middle Ages; little wonder then that farmers were grubbing up trees and not just scrub when corn prices were so high. ‘What immense quantities of timber have fallen before the axe and mattock to make way for corn,’ wrote one observer in 1801.

If you are felling and grubbing up fifteen acres of trees, felling them by hand and digging up the roots, when you get to an ancient yew, perhaps some thirty foot or more in circumference, magnificent and stately and – more importantly – notoriously hard to chop down, you might well leave it standing, along with its stile that allowed people on the track from the north to clamber into the woodland.

It was not only a mere but also a shelter. The presence of these evergreens in churchyards and elsewhere is often said to be because of the shelter they offer. Deer have been spotted sheltering under a yew at Ashridge Park, in Hertfordshire, and there are yews on the banks of John of Gaunt’s deer park at King’s Somborne, probably dating from when the deer park was set out in the thirteenth century. Of course, they can shelter more than game. An ancient yew at Leeds Castle in Kent was lived in by gypsies in 1833, and the hollow Boarhunt yew in Hampshire reputedly housed a family for a whole winter.

‘I know of no part of England more beautiful in its stile than Hertfordshire,’ wrote Sir John Parnell in 1769. Here the ancient fields were bordered by ancient hedgerows that were practically small strips of woodland. In an 1837 article lamenting the fall of an ancient yew in a hurricane, one eulogist wrote: ‘There are few objects of nature presenting more real interest to the mind, or richer points of beauty to the eye, than a noble aged tree; and at times these glories of the forest become associated, either from intrinsic character or local situation, with our best and purest feelings.’ We know that folk, and not just poets, loved trees. In Matilda Betham-Edwards’ novel about rural Suffolk in the 1840s, The Lord of the Harvest, Kara Sage the wife of the farm headman finds companionship in a magnificent elm. She ‘never tired of gazing at that ancient tree’. But we are told that in her love of nature she was ‘unlike her neighbours’. Still, she was not alone in literature: Thomas Hardy’s eponymous Woodlanders Marty South and Giles Winterborne were also said to be rare in their ‘level of intelligent intercourse with Nature’, when they knew by a glance at a trunk if a tree’s ‘heart were sound, or tainted with incipient decay; and by the state of its upper twigs the stratum that had been reached by its roots’.

Even if we doubt that in such a practical age someone left the tree standing simply for its grandeur, we cannot doubt the effect such a tree might have had on the superstitious – that fear may have stopped their axes. At Old Oswestry Hillfort in Shropshire, the countryside has been stripped of trees except for a single old yew. ‘It was probably spared because of a superstition about felling yews or because yews are very hard and so difficult to fell,’ suggests one Shropshire natural historian. In his 1896 article ‘Folk-Lore in Essex and Herts’, U. B. Chisenhale-Marsh wrote that ‘All about our own neighbourhood it is very customary, in clipping hedges, to leave small bushes or twigs standing at intervals, originally, no doubt, to keep away the evil spirits, or as propitiation to those that were cut away.’ What better way to appease the spirits of the vanished woodland than to leave them the sanctuary of an ancient yew, to watch, and wait, and guard the secret at its roots for a few years more?

8

Many writers at different times have engaged passionately by proxy in the fairy world. Most of the accounts of encounters in fairyland report incidents and adventures that occurred to someone else. This is the terrain of anecdote, ghost sightings, and old wives’ tales, of oral tradition, hearsay, superstition, and shaggy dog stories: once upon a time and far away among another people …

—Marina Warner, Once Upon a Time, 2014

‘Except for their gravestones and their children, they left nothing identifiable behind them,’ wrote historians George Rudé and Eric Hobsbawm of the nineteenth-century agricultural labourer, ‘for the marvellous surface of the British landscape, the work of their ploughs, spades and shears and the beasts they looked after bears no signature or mark such as the masons left on cathedrals.’ They are right that the traces are few, but the fields themselves carried names and sometimes they were the names of men who had worked them and, if the land bore names, so I expect did the men’s tools, their initials cut plainly into hafts alongside the initials of their fathers who swung them at other trees on other mornings. Did the yew tree itself also bear their names? One historian has noted that boundary trees ‘were deeply scored with carved and ever enlarging parish initials, from which the ivy was regularly stripped’. Did local men carve their names into the trunk of the yew as plainly as they did into the stone window jambs and leadwork of the Pelham churches? Even if they did, the tree is long gone, the tools are lost, and the field names are slipping from memory. Where now can we find Master Lawrence the carpenter and the labourers who believed in dragons?

In October 1904 the Hertfordshire historian Robert Andrews went to Anstey, a village next to Brent Pelham, chasing the legend of a secret tunnel, a blind fiddler and the devil. ‘The tenant of the little house at Cave Gate near Anstey was digging upon the premises held by him and found that the tool he was using suddenly sunk into the ground almost throwing him down,’ wrote Andrews. This tenant was old Thomas Skinner and he had found the entrance to a tunnel in the chalk. Skinner was a carpenter who had ‘passed his early years in the near neighbourhood’ and had recently retired to Cave Gate, ‘where he can, if he chooses, smoke his pipe under one of the most magnificent trees in Hertfordshire’. Perhaps it was while sitting under this tree talking to his guest about local folklore that he mentioned that in his boyhood his family had taken loppings from an ancient yew tree felled on the boundary of Great Pepsells field.

This was a tantalising reference. Not only did it place the felling of the tree in Thomas Skinner’s boyhood in the 1830s – tallying with the map and other evidence – but the Skinner family were agricultural labourers who just happened to share a house in Brent Pelham with another labourer, Thomas Lawrence, the cousin of the carpenter William Lawrence whose sons would one day become Wigram’s parish clerks. I would never know for sure, and it did not really matter, but I was unlikely to do better than to send these men to fell the tree one winter’s day in 1834.

Like many agricultural labourers in the early nineteenth century, the Skinners awoke in a single room in a house shared with another family. There was scant light on a winter’s morning and a ceiling open to the rough rafters did little to keep the place warm. If a labourer’s wife were house-proud, he would take his breakfast sitting on a chair varnished with homemade beer, and there might be bread with dripping washed down with ‘tea’ (made from burned toast), or perhaps ‘coffee’ (made from burned toast). Many labourers spent half their week’s wages on bread, but could not settle the baker’s bill until they had killed their pig at the end of the year. These are the generalisations of the historian, but the 1830s were not a happy time for agricultural labourers, especially in the winter months when trees were traditionally felled. Winter was also the time for job creation schemes (or as the historians of the rural poor, the Hammonds, put it in their inimical and depressing way, ‘Degrading and repulsive work was invented for those whom the farmer would not or could not employ’). One economic historian has estimated that 17 per cent of agricultural labourers were out of work in winter in the early 1830s. They would get poor relief, but it also meant that labourers could find themselves shared out between farmers who would find them things to do. The winter of 1834 was particularly bad, because the harvest had failed. ‘I am fearful we shall experience much difficulty this Winter in finding employment for the Poor,’ wrote a prominent Essex land agent, in a letter to his client, insisting they must reduce the burden of tithe payments that year.