Полная версия

Hollow Places

The way of life for those in the English countryside was changing more rapidly than at any time since the end of the Middle Ages; old beliefs and stories were disappearing as people turned their backs on the fields. The populations of cities like Manchester and Liverpool doubled in the first thirty years of the nineteenth century as labourers left the countryside in search of work. London saw its population increase by over 50 per cent to 1.6 million. This in a country of just fifteen million people. The first railway opened in September 1830 and was the prelude to the laying of 1,000 miles of iron and the synchronisation of clocks to the railway timetables before mid-century. Time itself was changing. The world was changing. Agricultural labourers were living in a countryside that had been pulled out from under their feet.

The agricultural revolution had changed everything. Customary rights of ordinary people were forgotten, enclosure meant they had nowhere to pasture their livestock, nowhere to collect wood or furze. The woods had been fenced for game by the new landlords from London, who were heedless of those customs that had been honoured time out of mind. Customs were replaced by laws.

It is for these new game laws that the social historians John and Barbara Hammond reserve their greatest ire in their classic The Village Labourer. The Laws of England that had shorn people of their rights and replaced their wages with charity, now threatened them with the gallows if they failed to resist the urge to vary their diet of roots by bagging a pheasant for the table. It is undeniable that, like William Cobbett, the Hammonds were purveyors of that particular style of the picturesque we might call the you-don’t-know-you’re-born school of history. Many historians would argue that things weren’t as bad as they claimed, and that enclosure was an essential component of the agricultural revolution that ultimately brought better standards of living to all. Yet it is telling that the man who was the high priest of agricultural progress, the great champion of enclosure, Arthur Young, had second thoughts in later life: he thought the human cost had been too high.

The Swing Riots that began in Kent in the summer of 1830 were as much about resisting change to a way of life as about money. Captain Swing was the name signed to letters sent to farmers and landowners across southern England, threatening arson, machine breaking and murder. They went hand-in-hand with a series of uprisings starting in Kent in the autumn of 1830. Barns and hayricks were burned, the new threshing machines – which ‘stole’ winter work from labourers – were smashed, and unpopular overseers and parsons hauled from parishes in dung carts. The agricultural labourers were demanding higher wages, reduced rents and lower tithes (so the farmers could afford to pay the wages). But it was not just about poverty. One of the complaints of a mob at Walden in Buckinghamshire during the Swing Riots was that buns used to be thrown from the church steeple and beer given away in the churchyard on Bun Day. They wanted the customs continued, but the parson refused. Traditions and customs and rights were ignored. The Furneux Pelham overseers accounts once contained the item ‘paid for ringing church bell for gleaners’. But gleaning – the right to pick up dropped corn during harvest – was being curtailed.

In 1834 there was a total overhaul of the Poor Laws, which would now be administered by Boards of Guardians in the big towns. Change was needed, but at the time it must have seemed like another of the links between a person, the place he lived, and the rights he had in that place, were being destroyed.

Belonging had mattered. Keith Snell looked at inscriptions on 16,000 gravestones in eighty-seven burial grounds to chart the use of the phrase ‘of this parish’ as in ‘To the memory of Mr James Smith late of this parish who departed this life 5th March 1830 aged 63’ and ‘Ellen, beloved wife of Thomas Tinworth of this parish died June 2nd 1888 aged 64 yrs’ – both in Brent Pelham churchyard. People had been proud of belonging, but by the 1870s examples became ever rarer.

Jacqueline Simpson has written that dragon legends ‘foster the community’s awareness of and pride in its own identity, its conviction that it is in some respect unusual, or even unique. That the lord of the manor should be descended from a dragon-slayer, that a dragon should once have roamed these very fields, or, best of all, that an ordinary lad from this very village should have outwitted and killed such a monster – these are claims to fame which any neighbouring community would be bound to envy.’

Those men did not only have a dragon legend to be proud of, they had a dragon-slayer in their village church and an ancient coffin lid to mark his resting place. Little wonder they thought first of dragons when they stared down into that great hollow in the earth.

11

Somewhere, perhaps, in the spaces between the pictures and the objects … lies a monument true to both us and the past.

—Mike Pitts in Making History: Antiquaries in Britain 1707–2007

Little is known of Mr John Morice of Upper Gower Street, London, other than the fact that in the 1830s he contracted a severe case of grangeritis: a condition coined by Holbrook Jackson in his Anatomy of Bibliomania to describe a ‘contagious and delirious mania endangering many books’.

Jackson was poking fun at the practice of grangerising or extra-illustrating books by re-binding them with pictures, often ruthlessly chopped out of other books. It was popularised by the followers of James Granger, a late eighteenth-century print collector and author. Although Granger did not paste his own vast collection of prints into published books, countless grangerites had theirs bound into his three-volume Biographical History (a catalogue of historical portraits from the reign of Egbert the Great to the Glorious Revolution). Granger’s surname became a verb: the first edition of the OED defined grangerise as ‘To illustrate (a book) by the addition of prints, engravings, etc., especially such as have been cut out of other books.’ And some of the most notorious cases of grangeritis involved grangerised ‘Grangers’, including one that expanded the original three volumes into a shelf-full of thirty-six, each as fat as the binding would allow.

Other popular titles to inflate were county histories, and it is one of these that was the cause of Mr John Morice’s affliction: Robert Clutterbuck’s recently published History and Antiquities of the County of Hertford. In the 1830s, Morice developed such an affinity for the History that he expanded its three volumes to ten, adding over 2,500 illustrations. The result would become known as the Knowsley Clutterbuck (after Knowsley Hall, seat of the Stanleys, earls of Derby who owned it for many years) and has been called the most sumptuous extra-illustrated county history ever conceived.

The chances that anonymous Mr Morice had played a bit part in the long history of Piers Shonks’ tomb were good because many of the illustrations were said to be original. When the Earl of Derby bought the volumes for 800 guineas in the late nineteenth century, the sales catalogue boasted of over 1,000 original landscapes, architectural views and portraits in neutral tints and watercolours, and 1,400 beautifully emblazoned coats of arms. A mere 550 additional engravings were acquired from other books. And this in a book that originally had only fifty-four pictures.

Among the best additions were those made in the 1830s by John Buckler and two of his sons, who appear to have landed their dream commission. The Bucklers were successful architects, but painting antiquities was their true vocation. Why draw new buildings when there were so many fine churches and manor houses to visit and preserve in ink? Reflecting on his career in 1849, John Buckler Snr wrote: ‘To build, repair, or survey warehouses and sash-windowed dwellings, however profitable, was so much less to my taste than perspective drawing with such subjects before me as cathedrals, abbeys and ancient parish churches, that I never made any effort to increase the number of my employments as an architect.’

Following page 450 of volume ten are six extra folio leaves. Pasted neatly in is an engraving of Shonks’ tomb, appropriated from some poor adulterated copy of the 1816 Antiquarian Itinerary. The picture is the Itinerary’s most important contribution to the history of the legend since the text was unoriginal. Drawn by the thirty-year-old Frederick Stockdale, an antiquary more often associated with the West Country, it is captioned ‘Remains of the Tomb of O Piers Shonks, Brent Pelham Church, Herts’. The composition is a little cramped, but mostly accurate, and captures the relief of the carvings although Stockdale chose to frame them in a rectangle, ignoring the shape of the coffin lid, and so the essential tombness is lost.

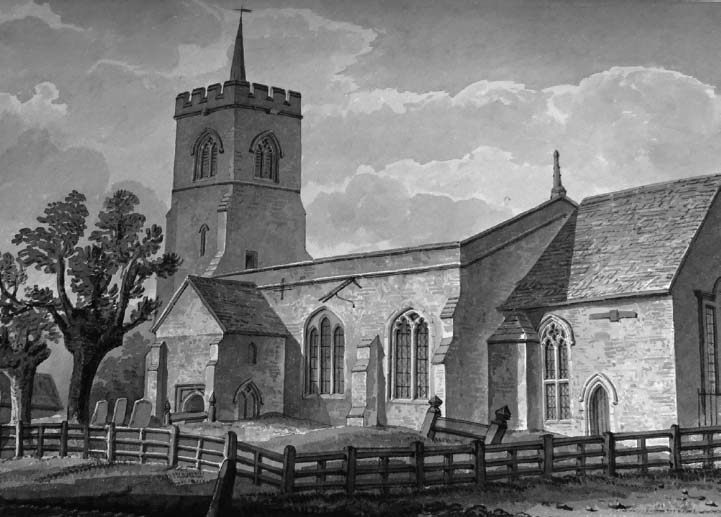

On the page facing Stockdale’s cannibalised drawing is something much more pleasing, real treasure: a unique sepia ink painting of Shonks’ tomb slab seen from directly overhead. Unusually for the prints in the Knowsley Clutterbuck, the signature and date have not been trimmed off. In the bottom left-hand corner it reads J. C. Buckler 1833. This was John Chessell Buckler, the eldest son, notable for coming second to Charles Barry in the 1836 competition to design the new Houses of Parliament. He first came to Brent Pelham in 1831 and produced three sepia watercolours: one each of Brent Pelham Hall, Beeches and St Mary’s Church – seen from the west or tower end. His father John Buckler visited the village in 1841 and painted a more complete view of the churchyard from the south-east, revealing that the nave was without a roof. John brought with him his youngest son George, who also painted three pictures in sepia: a view of the nave and font, another picture of Brent Pelham Hall seen from the churchyard, and lastly an interior view of the chancel screen with the two-faced royal arms mounted on them. The Bucklers liked to be thorough. The art historian Robert Wark has written that they were ‘fond of documenting a building from several points of view and over a period of time, especially if new construction or changes of some kind were taking place’.

The date on the picture of the tomb, 1833, is different to the other pictures. J. C. must have returned to Brent Pelham that year expressly to document the tomb. Perhaps he feared the weather pouring into the roofless nave was taking its toll on the interior, or perhaps the light had simply not been good enough during his first visit.

Buckler’s sketch picks out the four figures around a floriated cross, the large angel above it, and the dragon below. Of the eight known illustrations of the tomb, which predate the first known photograph in 1901, J. C. Buckler’s best captures the work of the mason. He is prepared to sacrifice detail to impression. He is trying to show that this is stone, and stone of great antiquity: the smudged blank face of the angel, the wear on the other figures slowly and inexorably being smoothed back into the block of marble by the passing of time and its blows and caresses. For an architect, he is surprisingly undraughtsman-like here. It is a work of art and not just a record of the tomb at a moment in time. The art and craftsmanship of the mason inspired Buckler to create something much more than just a topographical record.

When Holbrook Jackson called grangeritis ‘a contagious and delirious mania endangering many books’, he was concerned for the hundreds of books cut up and ruined to create one vast work, such as James Gibb’s grangerised Bible, which ran to sixty vast folio volumes, ‘each so thick that he could hardly lift it from the counter’. Jackson disapproved less, if at all, when books were not destroyed but instead collectors saved pictures from ephemeral publications such as newspapers and magazines or, better still, had new pictures specially made as John Morice did.

And yet Jackson, still tongue in cheek, called it a derangement for reasons other than the desecration of books for their prints. ‘Those afflicted by the derangement,’ Jackson writes, ‘are the most flagrant of all book-defectives.’ Why? Not just because they were handy with a pair of scissors, but also because they hunted for pictures ‘of every person place and thing in any way mentioned in the text or vaguely connected with its subject matter’. The grangeriser Richard Bull epitomised this habit of wild deviation or going off at tangents: a footnote referring to Audley End in the Reverend Granger’s Biographical History of England was an excuse to add fourteen large engravings of the palace to the volume. Although Alexander Sutherland was arguably the worst afflicted grangerite of them all, transforming the six volumes of Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion into no less than sixty-one volumes in elephant folio – each nearly two feet high – with over 19,000 extra illustrations (including 743 portraits of Charles I alone).

Behind the hyperbole of Jackson’s derision I sense a secret admiration for the grangeriser. Is their crime so very bad? After all, they give us unique pictures, and in some cases the only surviving record of buildings and views and monuments. On those days when I am overwhelmed by books, by my bookshelves, and the towers of books on the kitchen table and beside my bed demanding to be read, it has occurred to me that not just readers but writers ought to grangerise existing texts rather than fuel the anxiety of book lovers by making new ones. Paste in pictures, tip in reviews, scribble in the margins, insert maps and postcards, photos and poems and train tickets, draw pictures and diagrams, and eventually unpick the book and have it rebound. What else am I doing other than unpicking the story of Piers Shonks, collating what others have thought and said, chronicling my own journey, and inserting lots of new leaves? What better way to possess a much-loved text, to make it one’s own, than to grangerise it? What did Jackson say? They hunted for pictures ‘of every person place and thing in anyway mentioned in the text or vaguely connected with its subject matter’. Guilty as charged, and not just pictures. This book stands as testament to the technique; one that at times may be clumsy, but one by which hidden truths may be revealed. Something unique, and occasionally worth keeping, emerges simply from the juxtaposition of material. Putting all those Charles I portraits together in a particular order creates something that did not exist before; the deliberate or accidental meeting of one with another may reveal something or suggest something wonderful and previously unthought-of. Like my encounter with the Field of Cloth of Gold, here was a fingerpost pointing off the main highway to the trackways and holloways. Some would lead back to the main road, others would head across country to encounter – a pleasant surprise – other byways. Some would turn out to be dead ends, but they might be where the treasure is buried. All this hints at the process by which the legend itself came together and spread; a means to understanding how the folk legend grew by steady accumulation and accretion around the tomb – both deliberate and accidental – of images and rumours, half-remembered beliefs, the common store of folklore and tale, the theories of antiquaries and, only rarely, smatterings of historical truth.

The vogue for grangerising in the late eighteenth century was partly about the reinterpretation of the written word with the pictorial. The practice came into fashion just as the relationship between visual and verbal means of communication was changing. William Blake was mixing words and pictures to create something sublime, and the first illustrated Shakespeare appeared. This points us to the importance of the tomb as both image and text: its art to captivate and inspire us; its rich imagery, in which we can read its meaning, creatively and historically. It is likely that in the same way that a picture pasted into a book altered how the book was read, so with the passing of years the imagery of the tomb altered an oral tradition about somebody called Shonks. Perhaps. But only when I had exhausted that imagery – its original meaning and what it came to represent – would I have any idea of what that oral tradition might have been. It will be what is left.

The Knowsley Clutterbuck and the Buckler painting also pointed me to all those who had communed with the tomb to create images. Their drawings and paintings, with all their flaws – and the flaws contain their own important insights – helped explain the allure of the tomb and its capacity to conjure stories. The Bucklers and their fellow travellers (the prolific Mr Cole, the tragic Mr Oldfield, the meticulous Mr Anderson) are one of the organising principles of the second part of this book – the part that belongs to the tomb. They have wrestled with it in the shadows, tried to capture it, tried to decipher it. In many ways, the Shonks I tangle with here, is made of hatchings and brushstrokes on parchment: scribbles and shadows and smudges as much as percussions and chisel marks on stone.

12

… speaks to us from a forgotten world, drowned, mysterious, irrecoverable.

—May McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 1959

At Barley in Hertfordshire, between the 13th and the 14th milestones, the Cambridge to London road forked south-east towards the small village of Burnt Pelham. The man enduring the sloughs and mires of these notoriously bad roads one morning in 1743 was the twenty-nine-year-old William Cole. He was destined to be one of the great antiquaries of his age, gouty and ink-stained and only comfortable among old stones or old parchment. A Hogarth painting from around the time of his pilgrimage to Shonks’ tomb shows him standing in the background of a family portait examining old papers, perhaps less at home in the salon than in the muniment room. Would his scant worldliness stand the test of the man he was about to meet? Captain William Wright, the Lord of the Manor of Beeches, was known far and wide as ‘a man of great parts and wickedness’.

‘Great parts and wickedness.’ The phrase is somehow picturesquely archaic without losing any of its force. Wickedness as a noun is stronger than the adjective and especially if applied to a grown man and one in a position of power. ‘Great parts’ is the quiddity of the characterisation. I understand it as great means, but also talents and roles in life. Returning to Cole’s notes I find he considered the captain ‘a man of great natural and acquired understanding [who] knows much more than he cares to put into practise’. I Google ‘Great parts and wickedness’ to see if it is a literary allusion, something Richardson or Fielding wrote of a lecherous squire, but draw a blank. It gave me a type and I hope that it is a fair reckoning, but it is a harsh epitaph for anyone.

I imagine Cole entering the village on a dun-coloured horse that morning (comfortable carriage rides and the eighteenth-century Enlightenment were a long time coming to the Pelhams). Only thirty miles from London now, and yet according to one observer, it was a place both isolated and secluded and thus prone to superstitious fancies. Later, another would write uncharitably that, ‘The three Pelhams are in a dark state. The people very ignorant.’

1743 was notable as the year that George II became the last English monarch to lead an army into battle, but it would not be surprising if some in Brent Pelham had not heard that George I had died sixteen years earlier, or that his son was now king and embroiled in the quarrel over who should rule Austria.

Captain Wright was infamously slothful. He drove the Reverend Charles Wheatly to devote the page in his ledger facing the captain’s tithe payments to passages from scripture. He scribbled a proverb: ‘I went by the field of the slothful and by the vineyard of the man devoid of understanding. And, lo, it was all grown over with thorns, and nettles had covered the face thereof, and the stone wall thereof was broken down.’ (Proverbs 24:30–1). And ends with a psalm: ‘A fruitful land maketh he barren: for the wickedness of them that dwell therein.’ (Psalm 107:34). They are there as judgements and amulets against the captain’s laziness and supposed malignity.

Wright was a notorious miser. When Cole arrived, he was horrified that he had to stable his horse in the dairy and to find only two rooms with glass in the windows. The captain was holed up in one of them with hogs and dogs and litter and lice and ‘four strapping wenches who had nothing to do but obey their master and play at cards with him’. But Cole was willing to stomach the disreputable captain to satisfy his curiosity (and his taste for scandal). Wright was not only the current Lord of the Manor of Beeches, but also of the manors of Greys and Shonks, and, ‘the famous old monument of Piers Shonks … was the only reason which drew me out of my own province of Cambridgeshire into a church of this county,’ wrote Cole in a manuscript now in the British Library.

For all his bad parts, Captain Wright may have helped Cole. Perhaps one of his wenches accompanied him westward along the bridleway to the church and dangled a light while he pored over Shonks’ tomb. It is a Hogarthian composition, the single-minded scholar peering earnestly into the niche of the ancient tomb, the buxom (is that what Cole meant by ‘strapping’?) servant getting in his way, a suspicious sexton lurking in the background, and other stock village characters all arranged to lampoon Cole’s curiosity and the decrepit parish church.

In his prime, Cole would have made a great study for Thomas Rowlandson, who liked to caricature antiquaries. One of his contemporaries wrote of him, ‘With all his oddities he was a worthy and valuable man.’ It is the oddities we are interested in, and Rowlandson would have captured them as he hunkered over a tomb, measuring the exact length of the nose on the effigy, as Virginia Woolf imagined Cole doing in a letter she wrote to him post mortem, after reading his diaries. He became wedded to historical research while at Clare College Cambridge in the 1730s and later at King’s College, and, after being ordained the year after his visit to Burnt Pelham, he continued to put his research first. Woolf in her letter chastises Cole for not enjoying the eighteenth century. It was said he wanted to escape to the Middle Ages. She speculates that he was disappointed in love, which is why in later life he only loved his dun-coloured horse. He variously referred to his volumes as his wife, his children and his closest friends. By his death in 1789, he had compiled nearly a hundred large volumes of notes, transcripts and sketches, mainly on Cambridgeshire, and with remarkable industry; he told his friend Horace Walpole that ‘You will be astonished at the rapidity of my pen when you observe that this folio of four hundred pages with above a hundred coats of arms and other silly ornaments, was completed in six weeks.’

He rarely showed his papers to anyone. They were bequeathed to the British Museum on the proviso that they would not be opened until twenty years after his death, but even this term of grace was said to have caused some alarm for fear of what he had written about those he disagreed with – particularly anyone who had dared to remove his beloved stained glass from windows. He had no time for modernisers. Cole predicted that posterity might not appreciate the work he had done for it and admitted that he had committed his most private thoughts and much ‘scandalous rubbish’ to his papers. They were indeed deplored, when they were finally opened, as licentious and even morally reprehensible for mixing gossip, scandal and his personal prejudices with his antiquarian observations. If the nineteenth century was prurient and unkind to Cole, the early twentieth century found his historical notes, his journals and vast collection of correspondence invaluable and fascinating (especially the tittle-tattle), all written in his beautiful, easily legible hand.