Полная версия

Hollow Places

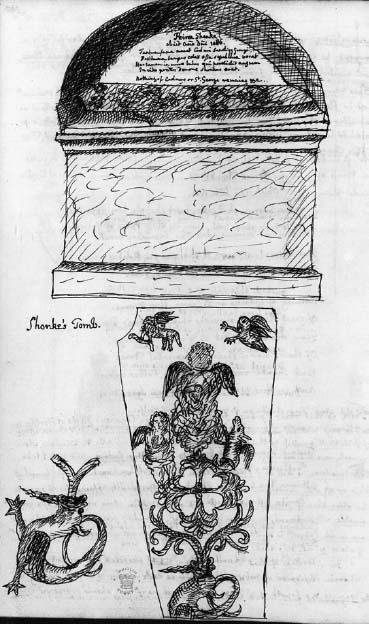

Cole took out his pen and ink that day in 1743 and made the earliest known sketch of the tomb. Like Buckler’s painting, Cole’s sketch was hidden away and forgotten; unlike Buckler’s painting, it is not art. It is a scratching, an aide-memoire, and in both its virtues and flaws reminds me that it is no easy matter to identify the detailed carvings on the tomb, let alone their meaning. He did capture those features that make it such an intriguing and mysterious object: its position in the wall of the nave, the strange inscription above it, and the grey-black marble slab with its extraordinary medieval carvings around which stories had gathered for centuries.

In drawing it, Cole seems to be the first writer to have examined the carvings in detail, and he tells us that the middle figure holds a smaller figure in its lap. Earlier writers had called the former a man, but as Cole’s sketch shows, it is an angel, a demi-angel, without legs, flying heavenwards, although the stumpy wings on Cole’s angel look hardly capable of flight. He gives it a scallop-edged costume reminiscent of something you would dress a baby in for its christening. The face has the features of a stick man: a long stick for the nose, a small one for the mouth. Oddly, these give it a patrician feel, he is curly haired with sideburns on his chubby face, shaded to a flush, and more eighteenth century than thirteenth.

In his Sepulchral Monuments of 1786, Richard Gough would explain that the angel is ‘conveying up a soul in a shroud, or sheet in the usual attitude’ – the ‘usual attitude’ being hands together in prayer. The image of a small naked figure – in this case probably male – standing in a napkin held by one or two angels has since been called a ‘stock symbol on monuments for the salvation of the soul’. The earliest known example can be seen on a beautiful slab in Ely Cathedral thought to commemorate Bishop Nigel who died in 1169.

Cole’s drawing is a scratching, but it is lovely: it reveals more than it obscures, while being far from precise. We can see the coffin shape of the slab. At its head end, he has drawn the four animals that represent the Evangelists: an angel for St Matthew, a winged lion for St Mark, an eagle for St John and a winged bull for St Luke. Cole has drawn a lion because he already knew he would find a lion representing St Mark, but it bears only a faint resemblance to what the mason put there. Cole’s lion faces us with the beard of an old sea captain, its forequarters raised semi-rampant upon a bow shape, its wings teardrops. Cole’s lion is too naturalistic, but his eagle seems to have rigor mortis, its legs grasping for something in the moment of death when it should be clutching a scroll. It is lumpy, with a parrot’s head, and looks incapable of flight. The bull or ox is dog-like, and St Matthew’s angel is awkward and timorous, hugging himself against the draughty nave.

The cross below the angel and soul is more feather dusters than the foliaged arms of a cross fleury, and its central boss has four petals and not five – such details are important when they come from an age when everything could carry a meaning. None of Cole’s sketches do justice to the hand of the mason, but he is not alone, the artists of Shonks’ tomb have often led commentators astray because the tomb has eluded capture on paper. Looking at his renderings, it is easy to understand how later, less educated observers than him mistook the lion, ox and eagle for three dogs, which quickly became part of the story.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.