Полная версия

Hollow Places

‘If stories remain undisturbed they die of neglect,’ writes Philip Pullman, and Italo Calvino said something similar when he justified his own tampering with Italian folk tales with a Tuscan proverb: ‘The tale is not beautiful if nothing is added to it.’ That is not to say anything goes. The wrong kind of change destroys more than it creates: you have to be true to the fact that people used to believe folk legends were true.

It was a clever bit of storytelling by the vicar, but we would not be happy if he had just made up the yew tree, the fields and the felling. We would feel cheated. As the folklorist Jacqueline Simpson has pointed out, we want a reason to say of our dragons and their slayings, ‘there was something in it after all’.

The realisation of Wigram’s conceit not only provided an unusually detailed instance of a folk legend metamorphosing – and perhaps a model for how other parts of the legend had been seeded or transformed – it completely changed the nature of my curiosity. I no longer had to wrestle with what it meant to find a cave under a tree that according to tradition grew over a dragon’s lair, because that was back to front: the tradition did not begin until the day the tree was felled. But the question remaining is even more curious: why on finding a cavity under a tree in a field with no previous connection to the legend did those nineteenth-century labourers think of the dragon that Shonks slew?

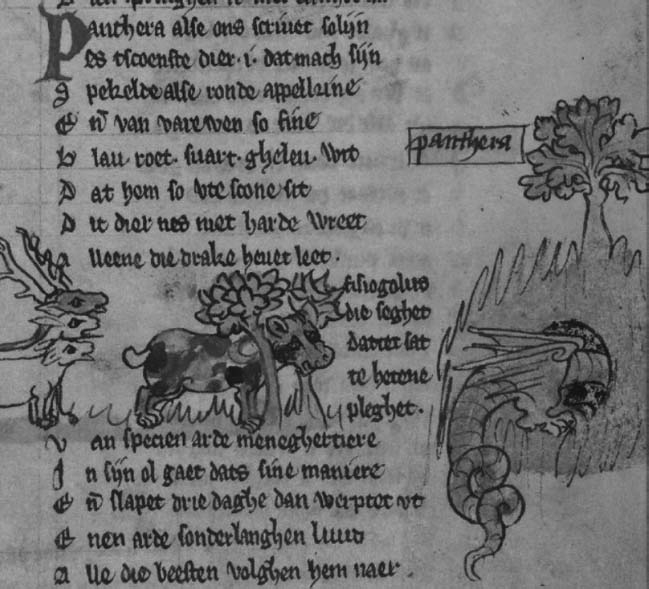

This hints at much about folk legends and their status within communities as recently as the 1830s. Stories about dragons and their holes are assumed to have medieval origins, conjured by medieval minds as they conjured up other strange creatures to populate bestiaries, adorn the edges of manuscripts and support the corbel tables of churches, but nineteenth-century agricultural labourers? Was the legend so powerful and so ubiquitous in the Pelhams that when uneducated farm workers found an unexpected cavity under a yew tree they immediately turned to the legend of a dragon-slayer for an explanation?

That such wonders hid in the fields and spinneys of the English countryside so recently is a delight, as well as a reminder that folk legends differed from folk tales – that were never believed and told only for entertainment – by the evidence in the real world as well as in the story: the hilltop, the gravestone, the tree that sages can point at and say: ‘You can still see it today’. It proves the legend.

I was first attracted to Shonks’ story by the yew tree in a named field. Finding such survivals, tangible evidence for stories and folk legends, is psychologically very appealing. At the beginning of Albion, her compendium of English folk legends, the folklorist Jennifer Westwood quotes Walter de la Mare: ‘Who would not treasure a fragment of Noah’s Ark, a lock of Absalom’s hair, Prester John’s thumb-ring, Scheherazade’s night lamp, a glove of Caesar’s or one of King Alfred’s burnt cakes?’

Such wonders have been called mnemonic bridges that help us connect with the past. It is the reason people have venerated fragments of the cross, or followed in the footsteps of Caesar and Alexander. It is the attraction of the perennial plot device in children’s stories where the young hero or heroine awakes in bed thinking they dreamed it all, only to find the golden coin in their dressing-gown pocket, proving they had really been there. Coleridge once imagined a dream about Paradise where he was given flowers and awoke to find them beside him, and Hans Christian Andersen knew the power of objects that crossed the boundary between fantasy and reality when at the end of his little story ‘The Princess and the Pea’ he wrote: ‘The pea was exhibited in the royal museum; and you can go there and see it, if it hasn’t been stolen. Now that was a real story!’

Objects that locate legends in a real landscape possess some archetypal magic. Some place the story in a distant, fantastical past, while others root it in the everyday. Some tales explain oddly shaped hills and standing stones by the antics of immense dragons, giants or the devil, but a yew tree in a field has the commonplace about it, the evidence is on a more human scale. There was a real tree, chopped down by real people, in a field with a name. It was important for the legend. Such things can be the reason stories prevail. Yet here was a strange instance of that rule because the yew did not ensure the survival of the legend by providing a regular, visible reminder of that story, since on the very day it became part of that story someone removed it from the landscape. It was an artefact, both in the sense that its significance lay in the workmanship of the woodcutters and in the sense that its place in the story was a remnant of the storytelling process. In spite of this, it undoubtedly helped to perpetuate the tale and did so largely thanks to Wigram’s rhetorical device.

The Shonks legend had the moat named for him and a mysterious tomb, and now it had a magical tree on the edge of Great Pepsells field as well.

5

Field names and Folk-lore are naturally classed together; both alike speak to us of the lives and customs of our forefathers; of creeds and cults, long since abandoned, but still surviving, though unrecognised, to these modern days.

—U. B. Chisenhale-Marsh, 1906

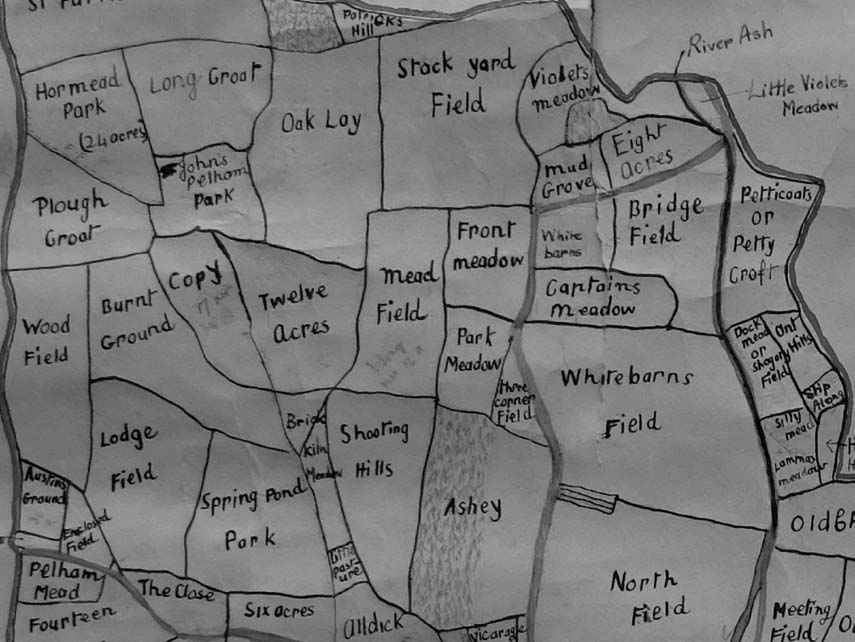

In the late 1930s, the English Place-Name Society asked schoolchildren to save the names of England’s fields before they were lost and forgotten for ever. In the fourteenth year of her forty-four-year reign as headmistress of Furneux Pelham School, Miss Evelyn Prior heard the call to arms and sent her pupils out to interview the farmers and field hands. The parish magazine for March 1937 records that: ‘With the aid of the school children and an Ordnance map and a few other helpers, and at the request of the County Council, Miss Prior, the headmistress of our school has drawn up a list of the names of all the fields of the parish.’

Did they find Great and Little Pepsells?

These names situate the yew in the real world, and evoke a bygone landscape. As with tithe customs, field names once again bring us into the territory of collective memories and tradition. The folklore collector Charlotte Burne said that all such ‘trifling relics’ were important for the study of social history: local sayings, rhymes, even the bell-jingles (the words that the different peals of church bells are supposed to ‘say’). ‘They reflect the rural life of past generations, with its anxieties, its trivialities, its intimate familiarity with Nature, and its strong local preoccupations.’ They helped make us what we are.

In Reverend Wigram’s day, the countryside was not numbered by bureaucrats but named by, and for, the people who worked it. Our landscapes and sense of the spaces around us were richer and more highly developed than today, or at least that is what the names would suggest. Today field names can help us recover that landscape from the blandscapes of modernity and to see our world with fresh eyes. Every parcel of cultivated land in the country had a name – more often than not one that can tell us something interesting about the land and put us in touch with the past.

It has been said that place names are linguistic fossils containing within them extinct words; they are often dense with information. They carry echoes of the dead, how they worked the land, their hopes and struggles, and the stories they told each other.

In many places, the fields themselves have disappeared. The London Borough of Ealing is not somewhere you naturally associate with the countryside, but it is the subject of the first of the English Place-Name Society’s series of Field-Name Studies written in 1976. Here beneath the pavements and Victorian villas are forgotten pastures that remember the names of local men known to have been on an early fourteenth-century list of the local militia. Other names will tell you where those men and their descendants built a dovecote, a menagerie, or ice house, where they quarried clay, farmed rabbits, or struggled to make crops grow in a stony field.

John Field, the aptly named historian and taxonomist of English field names, arranged them into useful categories. There are names that describe the shape of a field (Harps), its wild plants (Cockerels), the productivity of the land (Smallops), or long-lost buildings (Duffers). Its size (Pightle or Thousand Acres), how it was farmed (Lammas Meadow), and industrial uses (Brick Kiln Meadow). He came up with twenty-six types in all.

The meanings, as you have probably noticed, are not always self-explanatory, although Harps is easy: it should be a triangular-shaped field. Cockerels on the other hand is a false friend. Field names can morph in a process that gradually transforms a strange-sounding word into something familiar that seems to fit – philologists call this ‘popular etymology’. So Cockerels was originally Cocklers – from the weed corn cockle – and nothing to do with male chickens. Similar forces tinker with our folk tales and our urban myths, and in such ways dragons are sometimes born and giants set free to stalk the land. A well-known instance of popular etymology is Gravesend; there is one in Kent and another on the border of the Pelhams, and no doubt elsewhere. A friend told me recently that the local Gravesend was named for the plague victims who were buried there in the seventeenth century; she suspected this because Gravesend in Kent was apparently so-called because the London dead were washed down the Thames and ended up there, where they were buried. It is a good story, but a quick check of the place-name dictionaries tells us that both places were so-called centuries before the plague, before the Black Death even, and probably owed their monikers to local landowners called Graves.

Some field names have simply become mumbles of the original: how does Smallops tell us about the productivity of the land? For Smallops read Small Hopes. The meaning of Duffers has also been submerged in the argot of the agricultural labourer. For Duffers read Dovecote. Other names are made from obsolete words: a pightle is a small field, while a croat or croft is a small piece of land often attached to a house and usually enclosed. Thousand Acres is, of course, usually a very small field. If we ask why Lammas Meadow tells us something about how a field was farmed we can find an answer rich with history between Lamb Pits and Lamp Acre: ‘“Meadow lands used for grazing after 1 August”. The hay harvest occupied the time between 24 June and Lammas, when the fences were removed and the reapers turned their attention to the corn. The cattle were meanwhile allowed to graze on the aftermath. Loaves made from the new wheat were taken to the church at this time for a blessing and a thanksgiving – hence the name hlāfmæsse, “loaf festival”.’

Sometimes the name is the only surface remnant of a field’s claim to fame. There is no brick kiln to be seen in Brick Kiln Mead. Names can also help identify mysterious features still visible in the landscape. Aerial photographs reveal two circular mounds in a large field – ancient burial mounds perhaps? It is more likely they are remnants of a medieval coney, or rabbit, farm because it is remembered as The Warren. Other commonplaces of the medieval past live on only in the name: in the south-east corner of Furneux Pelham is Woolpits, which perhaps means ‘land near a wolf pit’. Although others have argued that rumours of wolves, like those of dragons, might just as easily refer to metaphorical beasts.

Field names remind me of Entish, the language of Tolkien’s giant tree shepherds, in which ‘real names tell you the story of the things they belong to’, but words in Entish were impossibly long agglomerations of meaning, so I suppose field names are in some ways the opposite: they contain much in a very small space, like poetry. Treebeard, the leader of the Ents declares that hill is ‘a hasty word for a thing that has stood here ever since this part of the world was shaped’, but Margaret Gelling counted some forty different words for a hill in Old English; after all, the Saxons needed to know one type of hill from the other when giving directions. The word hill may be lost somewhere in the name of the fields we are hunting for: Pepsells. The name is not in the field-name dictionaries, but some forty miles away, on the Bedfordshire border, there is a Pepsal End Farm with various spellings recorded, including in 1564 ‘Pepsel’. The meaning is ‘Pyppe’s Hill’ from the Anglo-Saxon personal name Pyppa, suggesting a very venerable field name indeed. Did Pyppa till the earth with Payn of Paynards – perhaps the oldest surviving field name in those parts – and with Peola, who gave his name to Pelham in the early days of the Anglo-Saxon migration? It is fun to think so, but it does not help us find the field we are looking for, a field where some once thought a dragon took up residence.

The schoolchildren did a wonderful job of collecting the names for Miss Prior and posterity. Across Hertfordshire as a whole, the operation was a great success. Two luminaries of the English Place-Name Society, Allen Mawer and Sir Frank Stenton, wrote: ‘We have been able in this county, possibly with more success than in any other that we have hitherto attempted, to get a lively picture of the field-names as they still survive and through the help of the schoolmasters and mistresses and their scholars we have again and again been able to obtain information which has been invaluable in throwing light upon the history of these names.’

The procedure was copied all over England and some of the information was used in lists in the early county volumes. The complete lists and maps were safely stored at University College London; safe until disaster struck in September 1940 when bombs fell from the sky. All the records were destroyed and the small number of names not already in print were lost along with their locations.

Fortunately, there are maps of Brent and Furneux Pelham rolled up in the Furneux church chest that are almost certainly the result of Miss Prior’s exertions. They are brittle and yellow: the parish boundary in red; the roads and woodland in green; the river, the field boundaries and their names marked in dark blue ink. The crossings-out, illegible pencil notes and childlike handwriting add to their charm.

Carefully unrolling the maps for the first time, I eagerly skimmed them in search of Pepsells, but could not see the name. I worked systematically from field to field following the names from Furneux Pelham church through Alldick and Little Pasture to the field boundary between Shooting Hills and Brick Kiln Meadow. I kept the pond on my left through Copy and skirted the ruins in Johns Pelham Park, emerging in Long Croat. Into Brent Pelham through St Patricks Hill, Chalky Field and Broadley Shot, my eye passed over 300 distinct field names: poetry like Moat Duffers, Malting Meadow and Mile Post Field, Ashey and Dumplings and Hitch. There were meads and leys, crofts, croats, pightles, springs and shots. Pepsells, great or small, was nowhere. Looking at that map for the first time, I began to entertain an idea that had not even occurred to me until that moment: what if Woolmore Wigram had just made the whole thing up? Maybe there never were a Great and Little Pepsells, no credulous labourers, no venerable yew set with a stile, not even a dragon’s lair.

6

It is distinctly remembered by the old inhabitants of these parishes that at the time the boundaries used to be trod a great deal of amusement was occasioned by the party always dragging with a rope one man through the ponds situated upon the heath.

—Thomas Bray, Meresman for Furneux Pelham

—John Cork, Meresman and Overseer of Albury Ordnance Survey Boundary Remark Book, 1875

In my mind’s eye I can see Major Barclay, tall and rangy, with very fine wind-blown hair, standing up to his knees in flood water one summer morning, trying to unblock the ditches on the Roman road by Chamberlains Moat and recalling the number of oyster shells found there when it was last dredged; on the tile-strewn platform at St John’s Pelham Moat on a summer’s evening explaining how a boy who went to his school started the First World War by insulting the Kaiser; or on Shonks’ Moat, leaning against an old oak tree which he calls Shonks: ‘There’s him himself,’ he says smiling. ‘He’s impressive close up, isn’t he?’

Ted Barclay has been fascinated by Shonks since his childhood when his grandfather Maurice told him stories about the hero. He is the current custodian of Beeches Manor and of all the Brent Pelham moats. In fact, he has owned much of Brent Pelham since the 1860s, or rather his family has, but Ted has the totally disarming habit of talking about the distant past as if recalling his own part in it. Casting his mind back perhaps to the day in 1905 when his great-grandfather played host to W. B. Gerish and the East Hertfordshire Archaeological Society, playing the immortal Comte de St Germain: ‘Hmmm. I told Shonks to stay at home that day there were dragons abroad.’

On the mezzanine stairs in his library are carvings taken from a staircase that was originally made for Brent Pelham Hall in the late seventeenth century. On the inside of the balusters, the head of Shonks’ dragon snarls with sabretooth fangs; on the outside, it bares its teeth in a demonic grin, breathing flames of foliage – opposites that nicely reflect the Barclays’ longstanding relationship to the story, which is both tongue-in-cheek and entirely in earnest. Ted’s father, Captain Charles Barclay, adopted a stray Irish wolfhound in the 1960s, which was promptly named Shonks. The three-foot-high beast proceeded to menace the neighbourhood, chasing cars, stealing food from kitchens and pulling clothes from washing lines, earning him immortality in Frank Sheardown’s book, The Working Longdog, in which Shonks the Dog’s most notorious exploit was to remove a dish of rice pudding from inside an oven: ‘How he did it, no one was able to tell, but did it he did and duly delivered the empty pot back home.’ The stuff of village legend.

The library is a recent addition to Beeches. The house was built in the seventeenth century and is dominated by nine exceedingly tall octagonal chimneys, with windows set in the stacks at the gable ends. The west wing is oddly stunted in contrast to the east, because six rooms were haunted and had to be demolished.

Ted pulled a small slipcase from the shelves and unfolded an old cloth-backed 25-inch Ordnance Survey map onto the carpet. It had been coloured and annotated over the years to show the extent of the Barclays’ Brent Pelham estate. Joseph Gurney Barclay, the banker and prominent Quaker, bought the manor of Brent Pelham in the middle of the nineteenth century and over time the family expanded their holdings, so the Barclays owned a fair portion of farmland in Furneux Pelham too. Surveying his domain, Ted traced a long finger across fields, across Nether Rackets, High Field and Lady Pightle.

He was looking for dragons and eventually tapped his finger on an irregularly shaped field defined by two blocks of ancient woodland: Great Hormead Park at the south-western corner and Patricks Wood on the eastern edge. It was labelled St Patricks Hill on the 1930s school map, but Ted was sure: this was Great Pepsells. After all, the land had been part of the Barclay estate for over a hundred years. It is in Furneux Pelham, bounded by Brent Pelham to the east and Great Hormead to the west.

If Ted was right, Woolmore Wigram may well have been telling the truth after all. There was certainly plenty of room for a dragon’s lair in the field, one of the largest in the Pelhams. Ted recalled that it had been the longest run of the steam plough, and during the Second World War the farmers filled it with old machinery to stop enemy planes landing. (Patricks Wood still concealed the rusting carcasses.)

Just so there could be no doubt, Ted produced an old notebook marked: Fields in Brent and Furneux Pelham: Owner-Occupiers-Area 1784. It was an eighteenth-century tithe book that had once belonged to a Robert Comyns, and inked into the columns of the first page were the fields owned by the Lord of the Manor in Furneux. There was no Great or Little Pepsells, but there were Pipsels and Pepsels in company with Nether Rackets, High Field and Lady Pightle, locating them just where Ted said they ought to be.

Great Pepsells was not the only field I discovered that day in Beeches. Next to the library in the old gunroom, hung a Victorian copy of ‘The Field of Cloth of Gold’. The original print was once famous for its vastness and for the man-hours expended to make it cover twelve square feet of plaster with so many tents and Tudor courtiers. Completed in 1773, it was the largest print ever made. The painter Edward Edwards spent 160 days at Windsor Castle copying the original oil for James Basire the Elder, who then took another two years to engrave the copper plate. Four hundred copies were pressed onto bespoke sheets of paper made for the occasion by the great paper-maker James Whatman in a sheet-size still known as Antiquarian. It was a print as ambitious as the event it commemorated.

It depicts the extraordinary pageant held in June 1520 when Henry VIII and the French King Francis I tried to outdo each other for excess and machismo in the Pale of Calais. Here was an endlessly diverting blend of historical detail, make-believe and mythmaking. Here were hundreds of richly costumed courtiers and halberdiers parading through a Barnum and Bailey landscape constructed specially for the occasion. The two larger-than-life kings embrace in a Big Top as knights gallop through the lists behind them, and men drink claret from fountains.

The Society of Antiquaries valued such paintings as historical documents, and scholars tried to tease out the factual from the fabulous – no easy task when the facts were so extraordinary anyway and the fabulous might symbolise much that was real. Take the statues of the three dragon-slayers on Henry’s extraordinary temporary palace. The showy Renaissance edifice was richly decorated with figures, but when Sydney Anglo published a detailed examination of the painting in the 1960s, he ruled that the dragon-slayers were figments of the painter’s imagination.

Another, much larger dragon, a magnificent, bearded wyvern, is painted in the sky above Calais. Whereas it is uncertain whether the painter portrayed the dragons on the gate accurately, presumably we can say with some confidence that there was no real dragon at the event, although chroniclers did write of one screaming through the sky above the crowd as Cardinal Wolsey sang the Corpus Christi mass. Historians cannot agree what this was. Some say that there was a ‘Flying Dragon’ firework display, others that it was perhaps a kite in the shape of a salamander released prematurely during the service. Whatever it was, it must have been a strange omen to some sixteenth-century minds. Today, the airborne dragon stands for the spirit of the piece: the myth and history, the real and the make-believe side by side. It stands as a cipher for all the fabulous but true features of the occasion, because ambitious as the painting and its print are, they cannot hold a torch to the real event.