The Book of Wonders

Arethas died sometime in the 930s. His was an impressive library but not a huge one; there were others collecting books, and his may well have been unremarkable in its own day. Nor did he always obtain the best texts of the works in which he was interested. And his reputation as a scholar has never at any time stood very high. But his library matters because, in part, it has survived to the present, providing some of the earliest known copies of some famous texts.

Eight of Arethas’ books survive, scattered today from Florence to Moscow. His copies of the works of Plato and Aristotle are important witnesses to the texts they contain, and the world owes to Arethas the only surviving copy of the Meditations of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, that long-lived favourite of later Stoic thought: Arethas had found an old manuscript, ‘not entirely fallen apart’, and had it recopied. His Elements is one of the two oldest complete copies of the text to survive, the other being an undated ninth-century book also from Byzantium.

It has fared no worse than many another artefact from the period. From about the tenth to the fourteenth century it was evidently much used and annotated. Owners and readers added to Arethas’ marginalia, sometimes in large, ugly handwriting and sometimes including large careless diagrams, which did something to spoil the look of the book. Someone added numbers to help understand one of the diagrams. Worse, a few early pages became detached and were lost, so that the first fourteen propositions of book 1 had to be replaced by a copy in a different hand.

The exact whereabouts of the manuscript during all this is uncertain; Greek books were coming to western Europe by various routes from the time of the Crusades onwards, but there is no sign of this particular volume in any records until it turned up in (probably) 1748, acquired for the collection of Jacques Philippe D’Orville, the Dutch-born son of a French family, who travelled in France, Italy and Germany before settling as a professor back in his native Amsterdam.

D’Orville had gradually acquired a large collection of manuscripts, among which Arethas’ Elements stood out as one of the oldest. On his death, the books passed to his son John and then his grandson; next they were sold to one J. Cleaver Banks, apparently a book dealer, and then in 1804 nearly all of the manuscripts were sold again to the Bodleian Library in Oxford, fetching £1,025. Recatalogued, the Elements became manuscript D’Orville 301.

The book remains in the Bodleian. Today, Arethas’ Elements is the oldest surviving manuscript of an ancient Greek author to bear a date. It is, indeed, the first dated manuscript in Greek minuscule writing, setting aside religious texts. Despite its age and its long journey – indeed, because of them – it is still beautiful. It is hard to look at it and not be moved.

Al-Hajjaj

Euclid in Baghdad

Baghdad, 14 Safar 204 AH (10 August 819). Dawn over the Round City. A little boy stands in a crowd.

I saw the caliph Ma’mun on his return from Khurasan. He had just left the Iron Gate and was on his way to Rusafa. The people were drawn up in two lines [to watch the caliph and his entourage go by] and my father held me up in his arms and said ‘That is Ma’mun and this is the year [two hundred] and four.’ I have remembered these words ever since: I was four at the time.

After six years of siege, Abu al-Abbas al-Ma’mun ibn Harun al-Rashid was returning to the city of his fathers. Heir to the caliphate, he was the inheritor of the spectacular conquests of the early Arab armies. Stretching across Egypt, the Fertile Crescent, Persia and India, it was almost the whole of what Alexander had taken a millennium before, and this empire was proving far more durable.

Of the three great heirs to the Roman Empire – the Greeks, the Arabs, the Latins – it was the Arabs who were the most dynamic, who most rapidly transformed a region beyond recognition. The vast world ruled by the caliphs stretched 4,000 miles from the Atlantic to the Oxus, funnelling goods, people and ideas through – and into – Iraq and Syria. Its wealth was incalculable.

Ma’mun’s dynasty, the Abbasids, came to power in 750. It would provide an unbroken line of caliphs for half a millennium, though its apogee came early, in the first century or two. Their values were universal and cosmopolitan, and they created a centralised Arabic, Islamic state around the caliph as commander, leader and lawmaker, with Turks and Iranians, Christians and Zoroastrians assimilated, employed and often powerful in their own right. Their story is the stuff of legend: Harun al-Rashid raiding against the Byzantines; the rise and fall of the Barmakid family; the execution of Ja’far, once the caliph’s right-hand man.

The Abbasids moved their capital – after a period of hesitation and experiment – to Baghdad in 762. It was the heartland of their political support and of the sources of their wealth: the rich alluvial plain of southern Iraq, watered by the Tigris and the Euphrates, growing wheat and barley, dates and other fruits.

Baghdad was close to the confluence of the two rivers: a great inland port as well as a centre of overland trade. Soon it became known as the Round City. The central government complex was a walled and ditched circle, built around a palace and a mosque, with wide arcades and generous courts. Suburbs and markets grew up around it; a separate palace – al-Khuld, the Palace of Eternity – was built beside the Tigris.

The city was a monument to the caliph who founded it, Abu Ja’far al-Mansur:

In the entire world, there has not been a city which could compare with Baghdad in size and splendour, or in the number of scholars and great personalities. The distinction of the notables and general populace serves to distinguish Baghdad from other cities, as does the vastness of its districts, the extent of its borders, and the great number of residences and palaces. Consider the numerous roads, thoroughfares, and localities, the markets and streets, the lanes, mosques and bathhouses, and the high roads and shops – all of these distinguish this city from all others, as does the pure air, the sweet water, and the cool shade. There is no place which is as temperate in summer and winter, and as salubrious in spring and autumn.

The palaces of Baghdad.

Francis Rawdon Chesney, Narrative of the Euphrates Expedition carried on by Order of the British Government during the years 1835, 1836, and 1837 (London, 1868), p. 406. (Archivac / Alamy Stock Photo)

The cultural mix in Iraq was an extraordinary one. There were Aramaic-speaking Christians and Jews in the country, Persian-speakers in the cities, and Arabs both Christian and Muslim. Meanwhile in Syria, Palestine and Egypt, Greek continued to be spoken alongside Arabic, as well as the Syriac and Hebrew into which quantities of Greek writing had now been translated. Along the lengthy border with Byzantium there were not just military skirmishes but cultural contact, bringing to the caliphate an awareness of just how much ancient Greek learning was still preserved.

Some Persian and Greek books had already been translated into Arabic, and now that the Abbasids were securely in power and their capital city was under construction, they turned to learning.

They had heard some mention of them by the bishops and priests among [their] Christian subjects, and man’s ability to think has (in any case) aspirations in the direction of the intellectual sciences. Abu Ja’far al-Mansur, therefore, sent to the Byzantine Emperor and asked him to send him translations of mathematical works. The Emperor sent him Euclid’s book and some works on physics. The Muslims read them and studied their contents. Their desire to obtain the rest of them grew.

In this first wave of translations are also mentioned works of Aristotle, Ptolemy and other Greek writers, as well as Persian and Syriac books and even those of Indian writers on astronomy.

The Arabic translator of Euclid was al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf ibn Matar, the son of a scholarly Christian family who was present at the foundation of Baghdad. Nothing more is recorded of his personal life or his activities: just that he translated Euclid’s Elements and Claudius Ptolemy’s astronomical work the Almagest during the decades around 800. One source places the initial arrival of a Greek copy of the Elements as early as 775. The Arabic sources report that al-Hajjaj’s version of Euclid was made at the request of al-Mansur’s successor Harun al-Rashid; some say of his vizier.

What was it like, this Arabic Elements? Some of the scholars of this period seem to have translated the sense of their texts rather than working word for word, but others stayed as close as possible to their models. The latter is perhaps more likely for this classic mathematical book; in any event, it seems unlikely that al-Hajjaj substantially reorganised the Euclidean text. But his was quite a succinct version of the Elements: he appears to have worked from a version somewhat shorter than the text that Stephanos copied in Byzantium, lacking a proposition here and there and often missing some of the repetitious setting-out, specification and conclusion to be found in the longer Greek versions. It also quite probably lacked books 14 and 15. The ravages of time have left more than twenty manuscripts of the Elements in Arabic, but none seems to contain al-Hajjaj’s version in anything much like its pure form, making its detailed character largely a matter of conjecture.

The burgeoning translation movement – and the reception of Euclid’s Elements in Arabic – were severely disrupted about half a century after the foundation of Baghdad. A war of succession broke out in 196 AH (AD 811) between the brothers al-Amin and al-Ma’mun, sons of Harun al-Rashid, and for more than a year al-Amin was besieged in Baghdad by his enemy’s forces. The city was devastated; suburbs were demolished and trenches dug; palaces were dismantled and their materials sold. Al-Amin was murdered in 198/813 but the fighting continued for another six years, with pillage and banditry from soldiers and vigilantes. Cultural and intellectual life surely came to a standstill.

Al-Ma’mun’s return to Baghdad after it was all over marked a new beginning. In the midst of pacifying and rebuilding, he and his ruling circle developed a court culture of refinement and sophistication, with a lively interest in the translation movement and the scientific texts it was accumulating. More than ever, Baghdad now became a magnet for texts and ideas: alongside Chang’an in the distant Tang empire it was the most literate city in the world. Al-Ma’mun founded (or perhaps re-founded) a library, the ‘House of Wisdom’, to store the scientific and philosophical knowledge that was being collected.

Al-Ma’mun’s personal enthusiasm was critically important, and the court followed his lead; courtiers used the patronage of translators as a way to establish their own prestige and competed in the hunt for manuscripts. The well-off outside the court, and the military elite, also became patrons of intellectuals. There were new missions to Byzantium, and collections of manuscripts came back to Baghdad for translation. Large personal libraries were amassed, and at one point more than a hundred booksellers worked in Baghdad. At its peak the translation movement was supported by the whole elite of Abbasid society, from princes and courtiers to officials and generals; it cut across ethnic and religious groups, involving speakers of Arabic, Syriac and Persian, Muslims, Christians, Zoroastrians and pagans.

Perhaps the most famous sponsors of translation were the three sons of Musa ibn-Shakir, collectively known as the Banu Musa. Close to al-Ma’mun, they spent lavishly, supporting a circle of professional translators and book-finders with monthly salaries. They took a particular interest in the mathematical sciences, but they, like the rest of Abbasid society, were willing to range across the whole of science and philosophy: astrology, alchemy, metaphysics, ethics, physics, zoology, botany, logic, medicine, pharmacology, military science, falconry …

As translation became a profession, the translators’ collective knowledge of Greek was improving, and the accuracy and range of their scientific terminology were increasing, meaning that older translations went out of date or needed to be updated. The early Arabic translators of scientific texts were, indeed, faced with an extraordinary task. Arabic is a language quite unrelated to Greek, with entirely different ways of managing syntax and word formation. For many technical terms, new Arabic words had to be devised, by borrowing or modifying Greek (or Syriac) words or by inventing new terms. The translators eventually created a scientific vocabulary that would be used for centuries, from North Africa to China.

In this heady atmosphere al-Hajjaj saw that it would be to his advantage to prepare a new version of his Elements. Technical terminology was still unstable and there may have been value in updating his version for that reason; it may be that he had seen new Greek texts that he wished to take into account. What later Arabic historians reported was that he decided to seek the favour of al-Ma’mun (or perhaps was commissioned by his vizier) by correcting, clarifying and shortening his Elements, making a version for specialists in which anything superfluous was deleted and anything missing was added.

Al-Hajjaj, or if not he then someone else in this first period of the Arabic Elements, also started a habit of giving names to certain of its propositions. One was called ‘the Mamunian’ – al-ma’muni – after the caliph who was al-Hajjaj’s second patron. Another – the so-called Pythagoras’ theorem – was called ‘the one with two horns’, applying rather incongruously to its diagram a traditional Arabic surname for Alexander the Great. Later in the book came the ‘goose’s foot’, the ‘peacock’s tail’ and even the ‘devil’. Presumably the names made it easier to remember which proposition was which or to recall the general shape of some of the diagrams: foot, tail or horns.

The mere fact that there was an audience of specialists – trained, interested people – to read this new, leaner version of the Arabic Elements is an indication of what the translation movement was achieving. Over the course of two centuries at least eighty Greek authors would be translated, including the big names such as Aristotle and Plato. Almost everything of Greek science and philosophy that had survived the wreck of the Roman Empire was rendered into Arabic during this period. It was a renaissance of learning on the largest possible scale, with profound consequences for the formation of an Islamic intellectual culture, which assimilated and developed not just Greek but Indian and Persian learning too.

The continuing flow of manuscripts to Baghdad meant that the story of Euclid in Arabic did not end with al-Hajjaj. Later in the ninth century another translator produced a fresh version. It was afterwards revised by a third man: Thabit ibn Qurra, one of the Banu Musa’s protégés. The Elements was becoming part of the stock of Arabic mathematical learning, to be worked over and rethought as needed.

It had become, indeed, the most important mathematical text in the Islamic world, central to the teaching of geometry and a stimulus to all manner of new mathematical work. It was corrected, summarised, added to, excerpted and frequently commented upon. Perhaps fifty Arabic commentaries on the Elements survive today, as well as Arabic translations of ancient Greek commentaries. Omar Khayyam, better known in the West as a poet, wrote a treatise explaining the difficulties in Euclid’s postulates; Ibn Sina, called Avicenna in the medieval Latin world, made a summary of the Elements as the geometrical part of an encyclopaedic work. In the tenth century an early writer on fractions went by the nickname ‘al-Uqlidisi’: meaning, most likely, that he made his living copying manuscripts of Euclid (Uqlidis). The Round City of al-Mansur was a ruin by then, but the Arabic Elements to which it had given birth lived on.

Adelard

The Latin Euclid

Bath, in south-west England, early in the twelfth century. Two men and two books. One book is in Arabic, and one of the men reads from it, translating as he goes into – probably – Spanish. The other listens to the Spanish and writes it down in Latin in his book. Word after word, page after page. There are stumbles over vocabulary, discussions about terms. The Latin Euclid is, gradually, born.

In the medieval story of Euclid, the Arabic versions hold unparalleled importance. From them, the text was translated on into versions in Sanskrit, Persian, perhaps Syriac, and other languages, some of which survive only in fragments. And it was translated into Latin.

For around half a millennium, educated citizens of the Western Roman Empire read Greek geometry in Greek, if they read it at all. Then for half a millennium and more after the Western Empire collapsed, they were reduced to mostly proof-free summaries of Euclidean results in Latin (see this book’s chapter on Hyginus in Part III for a fuller story). It is not clear that the whole – or anything like the whole – of the Elements was translated into Latin before the year 1000.

But, from late in the eleventh century, the Christians reconquered Spain and the Normans dominated Sicily, creating new possibilities for books in Greek or Arabic to pass into the Latin-speaking world. The new situation also made it much more possible for people who could read and write Latin to come into contact with those who could read Greek or Arabic. (The contemporaneous crusades in the eastern Mediterranean perhaps did rather less for cultural exchange, although the sale or plunder of Islamic libraries was certainly a factor in the movement of texts in this period. Saladin auctioned the famous Fatimid library from AD 1171 onwards, for instance; and in 1204 Constantinople itself, summit of Byzantine manuscript culture, was taken by the Latins.)

What followed was a translation movement comparable in its overall scope to the translation movement at Baghdad two centuries earlier: but this was decentralised, driven not by court patronage so much as by a new breed of sometimes itinerant lay teachers, hungry for texts. Translators worked at Barcelona, Tarazona, Segovia, León, Pamplona, and also north of the Pyrenees in Toulouse, Béziers, Narbonne and Marseilles. An intense enthusiasm for translation into Latin would last at least a century. Toledo would become a particularly important centre for translation and scholarship. Much of Arabic science and learning was translated into Latin during the twelfth century, and the consequences were incalculable.

Naturally the Arabic Elements was a part of this. The book was translated into Latin several times during the twelfth century, by scholars whose origins ranged from Chester in northern England to Cremona in Lombardy. The very first was done by a man whose life would qualify as an adventurous one in almost any period: Adelard of Bath.

Fastred was one of the tenants of the Bishop of Wells; he held land at Wells, Yatton and Banwell, all in Somerset. His son Adelard – Athelardus – was born in about 1080: less than a generation after the Norman conquest of England. He was clever, perhaps extremely so, and the combination of his family’s means and perhaps patronage, and the new situation of a Norman-controlled England, combined to provide exciting possibilities for his education. He went to France, to Tours, studied the liberal arts and showed a particular interest in astronomy. He learned music and played – by invitation – before the queen. He wrote a dramatic dialogue in the manner of Boethius, exhorting youths to the study of philosophy.

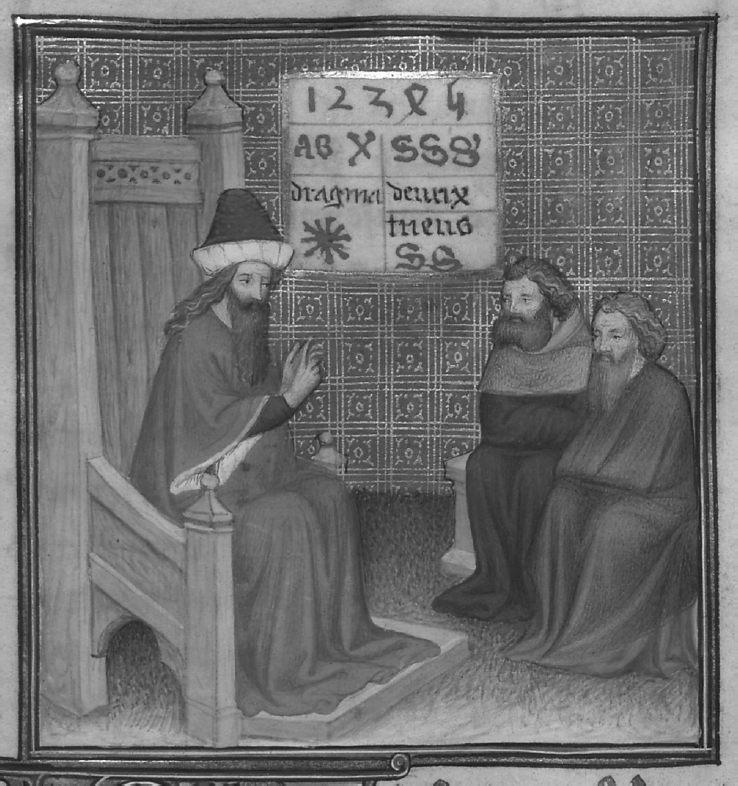

Adelard of Bath.

Leiden University Libraries, SCA 1, fol. 2r. (Leiden University Libraries/Creative Commons Attribution International, CC-BY 4.0)

He could have become a career cleric or perhaps an administrator at court. But instead he went travelling. Leaving behind a nephew to concentrate on the tamer Gallic studies (the nephew, from Adelard’s own writings about his life, may possibly be a fiction), he set out in search of the novelty of the age: Arabic learning.

In an instance of what might well be called Crusade tourism, he made his way to the Norman kingdom of Antioch in Syria, taking in Salerno and perhaps Sicily and Cilicia along the way. He saw an earthquake in Syria, a pneumatic experiment in Italy, met a Greek philosopher and learned that light travels faster than sound. Adelard, in other words, appears to have travelled from England to the border with the Islamic empire – without any official protection or support – just to seek the knowledge of that other civilisation. The success of the first Crusade in 1098 had produced something of a vogue for visiting the Middle East, but it was far from usual for scholars to travel in that direction for the specific purpose of encountering Arabic science.

Adelard certainly succeeded in encountering Arabic scientific texts, including astrological books, astronomical tables and Euclid’s Elements. But the details become lamentably obscure at this point. His astronomical tables were calculated for use at Cordova, and the most natural place to find an Arabic Elements would also have been reconquered Spain. But Adelard, despite a tendency to show off about his travels, never said that he had been to the Iberian Peninsula. Thus, there is something of a mystery.

During the 1120s, Adelard returned to England. He turns up in legal and court records in the area of Bath, though his name was not quite unusual enough to be sure that every such report refers to the same man. This was a turbulent period for England, and it looks as though Adelard may have supported first King Stephen and later his rival Matilda; he dedicated a book to her son, the future Henry II. He was quite probably associated with a circle of learned clerics around the Bishop of Hereford and Walcher and Prior of Malvern. He wrote on astrology, translated the astronomical tables of al-Khwarizmi (head of the library of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad) and wrote a work of natural philosophy drawing in a general way on his knowledge of Arabic ideas. He taught, and wrote a little book about falconry. And he translated the Elements of Euclid from Arabic, probably shortly before 1130.

As one historian remarks, ‘nothing in his life so far has prepared us for this’. It is not altogether clear what had prepared Adelard for it, who nowhere stated that he could read Arabic. The writings of his earlier life betray no special knowledge of geometry nor particular interest in the subject, although he certainly knew some practical writings about surveying and may have seen a Latin summary of the Elements.

Prepared or not, it is remarkable to think of translating a book of the length and complexity of the Elements in the conditions of the time: the more so as Adelard presumably did the work after he was back in Bath, the better part of 1,000 miles from any location where Arabic was spoken. Yet it is likely that he did have some linguistic help.