The Book of Wonders

The library lived through it all. The Ptolemies’ bibliomania gave it a size that contemporaries could only guess at. One suggested there were nearly half a million scrolls there: surely an impossible number; but whatever the arithmetic in miles of text or acres of papyrus, it was a storehouse of all that was Greek and all that could be amassed and translated into Greek. A most celebrated symbol of its cosmopolitanism was the translation of the Jewish scriptures into Greek during the third and second centuries BC.

But books are fragile, and libraries are fragile. Cultural institutions are not everyone’s priority when political instability sets in. Julius Caesar accidentally set the city on fire in 47 BC, and an enduring – and probably true – report says that some books were destroyed, perhaps in seafront warehouses. On the other hand, there was certainly still a functioning library a century later. And the Museum itself continued, even throve at first, under the patronage of the Roman emperors.

But the Roman period saw civil war and riot with at least the usual frequency for a city of such a size: the Alexandrians in fact acquired a reputation for mob violence during their first Roman centuries. In the late third century, civil war reduced the whole of the old palace quarter to ‘desert’, in the words of one witness, and there was most likely little left of library or Museum after that. It is impossible to be certain. In the evidence that survives, the last employee of the Museum was Theon, who taught mathematics from around 360 until perhaps the end of the century.

Whatever the details of its long demise, the tradition of scholarship at the library had been a crucially important one for the shaping and the sheer survival of Greek literature. Practically every Greek text of any length that survived at all passed through the Alexandrian library.

The library developed a specialism in textual criticism of older literature, studying questions like: what did the authors really write? Which books are authentic? Which lines have been garbled in transmission? It was here that there arose the long-lived metaphor of the corrupt text, the text that needed to be cured, purified of the dirt and disease it had acquired through contact with human beings.

The scholars at the library devised signs for recording which lines of a text were doubtful, and how and where they had emended it. They began to invent marks for section divisions; even line divisions. No punctuation proper; texts were still transmitted in ‘continuous writing’:

ALLINCAPITALSWITHNOWORDBREAKSACCENTSORPUNCTUA TIONOFANYKINDANDTHEREFOREREALLYHARDTOREAD.

These techniques and innovations were developed for the study and transmission of literary classics: Homer first, following a tradition of interpretation that went back to the Homeric reciters of classical Athens, and then the Athenian playwrights and others. The scholars at the library had less to say about prose, and less again about scientific texts; there is no evidence that Aristotle’s books, for instance, were worked on in this way at Alexandria. To work on mathematics required perhaps a slightly different approach, although the idea of textual purification was the same.

The text of Euclid’s Elements was already unstable in some ways during its first few centuries; the surviving evidence hints at more. It is quite possible that Euclid himself prepared more than one edition of the Elements, which would help to account for some of the variation the book shows in the evidence that survives. It is at least equally possible that zealous editors got to work on the text during the second and first centuries BC, producing versions that differed from the original and perhaps from one another.

What is certain is that by at least the first century AD, and continuing until at least the fifth century, there was a tradition in Greek – and often at Alexandria – of writing commentaries on the Elements. Was a definition missing? Was a term defined but not subsequently used? Was a proposition a ‘dead end’, never used to prove anything else? Did it come in the wrong place, after something it was supposed to help prove? All of those things could be pointed out in a commentary, to help teachers and students use the text, to help them avoid stumbling over such minor wrinkles. Commentary of this kind could hardly avoid suggesting changes to the Euclidean text itself, and so it provided raw material to the different but overlapping activity of editing the text: preparing a new version of it for the use of, say, one’s own students.

And so to Theon, and the last days of the Museum. He taught, and he dedicated books to his students. He wrote commentaries – most likely based on his lectures – on the second-century astronomical works of Claudius Ptolemy (no relation, as far as is known, of the royal house of the Ptolemies. On his so-called Handy Tables he even wrote two different commentaries: one for competent astronomers, and one for those who could not yet understand the reasoning and the mathematics the book contained. He also seems to have written on the interpretation of omens and on the Orphic hymns. A handful of his poems survive, in which he expressed his devotion to the perfect world of the heavens, the gods and the stars.

And he also prepared editions: consistent, improved versions of classic texts for use in his teaching. He certainly worked in this mode on the Elements and other works of Euclid, and on the works of Ptolemy such as the Almagest, doing what various other editors did to mathematical texts during this period. He cleaned up and smoothed out difficulties. He chose between variant versions of the texts, or combined the variants together to give a text with, sometimes, two alternative proofs for a single proposition. He filled in gaps, real or imagined. While the Homeric editors saw themselves standing outside the epic tradition, mathematicians of later Alexandria tended to behave as though Euclid was a colleague, and they themselves members of a still-living tradition. Instead of textual purity and fidelity (‘what did Euclid really write?’) they prized correctness, completeness and usability.

Most unusually, Theon actually left a record of one of his specific changes to the Elements. In another work – his commentary on Ptolemy – he mentioned it, a certain minor point that ‘we have proved in our edition of the Elements at the end of the sixth book’. Thus he recorded for posterity that a certain fragment of the text was his, and that that was the kind of thing he did.

The proposition in question says that if you take a slice out of a circle – like a slice of cake, with two straight lines meeting at the centre – then the length of its curved side is in proportion to the angle at the centre. Theon’s addition says that the area of the slice is also in proportion to the angle at the centre. It is easy to believe that it is true, and not at all hard to prove.

Theon’s throwaway comment has received an enormous amount of attention from scholars of the Elements over the years, since it seems to raise the tantalising possibility of seeing beneath the editorial accretions of the ancient world, to the real Euclid beneath. If the type of thing Theon did can be securely described, perhaps later scholars can recognise his modifications elsewhere and reverse them.

Unfortunately, attributing specific modifications to Theon other than this one proves to be a very doubtful business, although many have tried. One person’s logical gap is another person’s elegant brevity. One person’s Theonine interpolation is another person’s authentic Euclidean blunder. The evidence – most of it far, far later than Theon, and the subject of endless cross-contamination between Theon’s version and the version or versions that preceded him – does not allow anything like certainty.

History, meanwhile, has not been kind to Theon himself. Later ages would have different attitudes to text and authenticity, and would not be too impressed with the kind of modification in which he and his like engaged. Recent historians have characterised his editions as ‘trivial reworkings’, ‘mathematically banal’, and his scholarship as ‘completely unoriginal’. His biographer in the Dictionary of Scientific Biography is frankly devastating: ‘for a man of such mediocrity Theon was uncommonly influential’.

Perhaps it is not necessary to be quite so hard on him, particularly if he was doing his work with teaching in mind. To be sure, there are things in Euclid’s Elements that are ‘elementary’ in the sense of easy; quite a lot of them, ranging across simple constructions with lines and circles and triangles through the properties of numbers (even times even is even) and those of ratios. But the book also contains a great deal that is eye-wateringly hard by any standard whatever, and which requires a real talent for mathematics, and a lot of time spent on its study. An example is Euclid’s exhaustive classification – in book 10 of the Elements – of the different ways two lengths can make a ratio that is impossible to express using whole numbers: there are 115 propositions about the subject. Another is the construction of the tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron and icosahedron, and their relative sizes when set inside a sphere that just touches the corners of each of them. It is certainly possible to imagine students for whom Theon’s smoothing, explaining and organising would have been of real help.

Influential he certainly was. Although older texts of the Elements remained in circulation, Theon’s new edition was taken up enthusiastically, and nearly all of the complete manuscripts that have survived to the present contain what seems to be Theon’s version. Mediocrity or not, he had more impact on the Euclidean text than anyone else since Euclid.

The sharp-eyed will have noticed a reference to Theon’s daughter. Her name was Hypatia, she was born around 355, and early sources suggest her mathematical talents surpassed those of her father, although only the titles of her works survive. These seem to have included commentaries and possibly independent works in mathematics and astronomy.

Theon was living in a changing world. The emperor Constantine had converted – at least formally – to Christianity in 312, and removed the legal obstacles to Christian worship the following year. Churches were opening and – slowly – temples were closing across the Greek world. During Theon’s lifetime the temple of Serapis in Alexandria was destroyed: seat of Ptolemy’s novel cult, it had been closed since 325, but it was probably one of the main remaining libraries in the city.

The Alexandrian reputation for mob violence continued, and Hypatia herself was one of its victims. By the early 390s she was active as a teacher of philosophy, with an established circle of students. Her teaching included geometry, and she is therefore one of the last recorded individuals who continued the tradition of geometrical teaching in the city of the Elements’ birth: a well-known figure, even something of a celebrity in the city. Most of her identifiable students were – or later became – Christians, and her paganism does not seem to have been felt as a problem. But in the 410s her supporter the Roman prefect (Orestes, another Christian) came into violent conflict with the Alexandrian patriarch, and in March 415 Hypatia herself was murdered in something like reprisal: a victim, in the words of one ancient historian, of political jealousy. Since the nineteenth century the tragedy has been often – and often sensationally – fictionalised.

One of Theon’s astronomical commentaries bears an ambiguous heading referring to his daughter. It has been variously interpreted as implying that Hypatia checked or revised that part of the commentary (or more), or that she edited or revised part or all of the text on which Theon was commenting. Certainly it seems there was a period when she and Theon worked together on mathematical and astronomical material. But the surviving evidence does not link her with his edition of Euclid’s Elements. It is possible she did work on it with him, and tempting to speculate that the future teacher of geometry left her mark, somewhere, on the text of the Elements. But Theon’s career certainly began before his period of collaboration with his daughter, and most probably continued after it, meaning that he could equally well have edited Euclid independently of her. As with so much about the transmission of the Elements, it is impossible to be sure.

Stephanos the scribe

Euclid in Byzantium

Constantinople, in the 6,397th year of the world (AD 888). The scriptorium in one of the city’s monasteries.

The last page of vellum turns. The scribe flexes his weary fingers, stretches his aching back, and adds a final note:

Written in the hand of the clerk Stephanos in the month of September, the seventh indiction, the year of the world 6397. Purchased by Arethas of Patras, the price of the book 14 coins.

During the fifth century the Roman imperial system collapsed in the western part of the empire, from Britain to Portugal to the Balkans. By 480 there was no emperor. In the eastern part, which spoke Greek and had had its own separate emperor since 395, the empire flourished for another 1,000 years. The seat of its power was in Byzantium.

Byzántion. Constantinople. Another immense vanity project, it was founded in 324 as a new de facto Eastern capital, and designated the official capital from 330. A university of sorts opened in 425.

This empire was less prosperous, and less literate than its predecessor. Schools – the universities of the period – existed at Alexandria, Antioch, Athens, Beirut, Constantinople and Gaza. But they declined, and by the middle of the sixth century only those at Constantinople and Alexandria remained. The latter was conquered by Persia in 619, ruled by the caliphs from 641. The Greek-speaking world collapsed; Greek culture was now largely that of a single city, Constantinople.

If the barbarians had provided a solution of sorts to the problems of Rome’s unwieldy empire, the great contraction of culture provided a similar sort of solution to the unwieldy mass of Greek literature. The production of Greek books slowed dramatically, and what was not salvaged at Constantinople was, by and large, not salvaged at all. The worms got the rest, and the Greek world’s library was a manageable size once again.

For teaching purposes, the Byzantine scholars organised matters into a literary cycle and a scientific cycle, together making the ‘seven liberal arts’ that were also studied in the West. The list of seven subjects went back to classical Athens; it is not really certain when or where it was formalised into a curriculum, perhaps around 100 BC. On the literary side there were grammar, rhetoric and dialectic (logic), which amounted to three different ways of reading the favoured ancient authors. On the mathematical side there were arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music. The authorities for these subjects ranged from late classical authors such as Aristoxenus on music, down to Greek authors of the Roman period such as Claudius Ptolemy on astronomy. On geometry, of course, the text to study was Euclid’s. For the first time, then, it is clear that knowledge of the Elements was part of a good education, mastery of it a requisite for those aspiring to join the cultural elite. Or at least, presumably, mastery of the easier parts.

Saving culture with limited resources, particularly when the priority was teaching tomorrow’s orators, did odd things to texts. It did them to the Elements. Scribes made mistakes; when they were copying mathematics that they did not always understand, they made particular kinds of mistakes, confusing numbers, abbreviated words and the names of geometrical points, all of which used the same set of Greek capital letters, sometimes in the same sentence.

Since readability rather than literality was their main value, scribes also made deliberate improvements, standardising notation, tidying up diagrams, even regularising the logical structure of proofs. Some compared the two versions of the Elements now in circulation – Theon’s edition and the version that preceded it – and adopted whichever text they preferred at any given point. Coherence and mathematical perfection resulted, perhaps, but at the expense of obscuring Euclid’s distinctive voice.

All this was taking place not on the papyrus rolls that Euclid used but on codices – books with pages – that had gradually supplanted them. A single codex could be large enough to hold the whole of the Elements, with commentary in the margins too: and that created further possibilities for confusion, when scribes copied pieces of commentary into the main text by mistake, or adopted as main-text readings what were proposed in the commentary as alternatives or improvements. Even when that did not happen, fragments of commentary became enduringly attached to the text as ‘scholia’, transmitted for generations and often completely detached from their original commentary context.

It was probably in the fifth or sixth century, too, that someone added Hypsicles’ treatise on the solids to the Elements, calling it book 14, and there it remained, enough scribes accepting the addition to give it a sort of authenticity of its own as a completion of what Euclid had supposedly left incomplete. Most likely in the same period, a fifteenth book was also added, addressing further questions in solid geometry. Although it was sometimes also associated with the name of Hypsicles, it was in reality a combination of material from at least three authors, of whom the latest was Isidorus of Miletus, the sixth-century architect of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. It may indeed have been one of his pupils who assembled the fifteenth book and added it to the Elements.

The Byzantine literary world itself suffered serious disruption from around 550 to 850, with many of its institutions dormant or closed. The empire was at war with the caliphate (almost always) and the Bulgarian khanate (usually) and in conflict with the Roman Pope and the Carolingian empire (occasionally). And it was stirred internally by seemingly endless theological controversy and the hopeless muddle of the imperial succession. In the ninth century came a period of self-conscious revival and rediscovery; the imperial university reopened, and the names of certain teachers have been preserved: Leo the mathematician, Theodore the geometrician, Theodegius the astronomer, Cometas the literary scholar.

These scholars collected books. Leo, for instance, undoubtedly had copies of the works of Euclid; he also had copies of Apollonius’ book on conic sections and of works by Theon and by Proclus, as well as those of Archimedes and very likely of the astronomer Ptolemy. Books were now being copied in a new, ‘minuscule’ handwriting, smaller and easier to read than the old all-capital style, and better supplied with breath-marks and accents. And scribes still perhaps blundered, improved, and sifted the existing versions of texts for what struck them as best. Half the definitions and a third of the propositions in the Elements were by now affected by changes from a thousand years of commentary and editing.

Arethas of Patras was another of the scholars of this period, and evidently also a man who loved beautiful books. Born shortly after 850 in western Greece, he came to Constantinople and received a comprehensive classical education, reading widely in ancient literature. His career was in the church; he became a deacon by 895, and in 902 or 903 Archbishop of Caesarea, the most senior see dependent on Constantinople. He was an author and editor, and the writer of a commentary on the Apocalypse. A few of his letters survive, and a few of his epigrams. Along the way, he collected books.

He owned, by his death, twenty-four of the dialogues of Plato, and the main works of Aristotle. He had copies of the ancient authors Lucian, Aristides, Dio Chrysostom, Aurelius, and of Christian writers such as Justin, Athenagoras, Clement of Alexandria and the church historian Eusebius. The best of Arethas’ books were masterpieces of calligraphy on high-quality parchment. He paid twenty-one gold pieces for his copy of the works of Plato, when Civil Service salaries started at seventy-two per year. He commissioned his books from professional scribes, most of them monks; some were the finest calligraphers of their period. (A measure of the high-pressure perfectionism that ruled in the Byzantine scriptoria is that one of them had a specific penalty for breaking your pen in anger.)

And, of course, Arethas obtained a copy of the Elements. In fact, it seems to have been the first book he commissioned; perhaps in connection with the completion of his education in the seven liberal arts. Stephanos, its scribe, was one of the most accomplished of all Byzantine calligraphers. He worked for various patrons; copies survive of the Acts of the Apostles and the New Testament Epistles in his hand, and works by such authors as Ptolemy, Porphyry and Proclus in hands that may be his. He developed a characteristic decorative scheme in blue and gold, with cypresses, columns, lanterns, crosses and geometric figures such as rhombuses, circles, squares and rectangles. And he developed a spacious layout, with wide margins where notes and commentary could appear without making the page look messy.

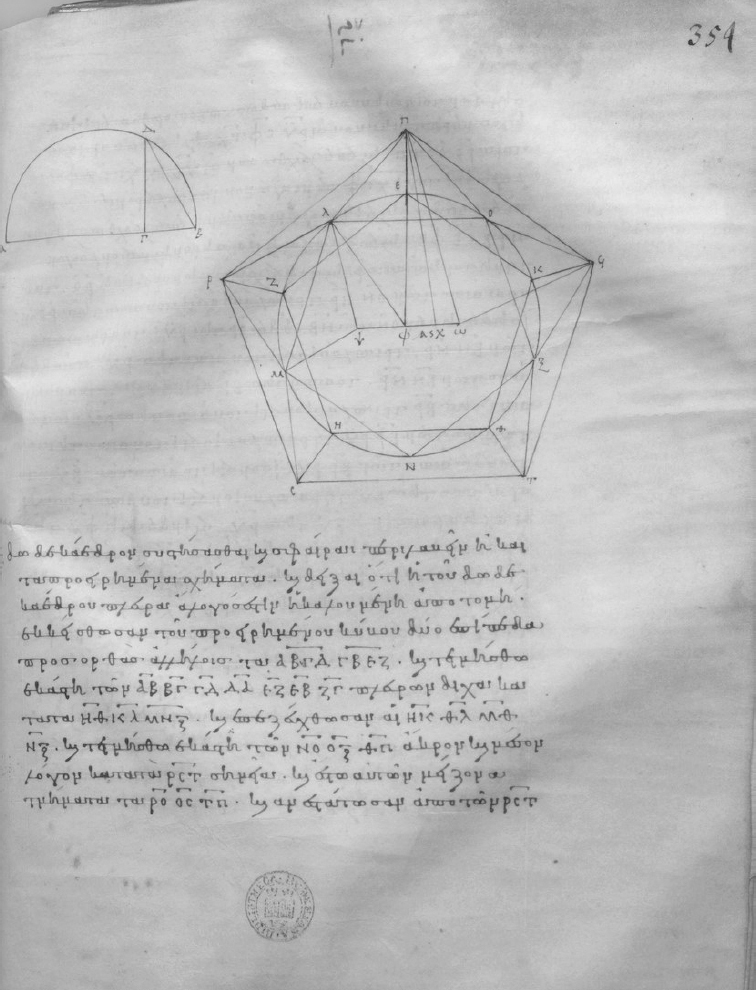

The Elements in 888.

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS D’Orville 301, fol. 268r. (The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo)

All of this he brought to Arethas’ copy of the Elements in 888: 388 leaves of parchment in forty-eight gatherings, bound together to make a thick book seven inches by nine. At up to twenty-six lines to a page, there were nearly 20,000 lines of text all told, in a pleasing reddish-brown ink. Stephanos reported at the end of book thirteen that what he had copied was ‘Theon’s edition’; he went on to copy out books 14 and 15 as ‘Hypsicles’ addition’.

The diagrams were drawn – it is hard to be certain whether Stephanos did them himself – neatly, with rule and compass, and their labels added in capital letters. They were inserted into spaces in the main text that had been left blank on purpose: always on the right, and always a good legible size.

Arethas didn’t like his books just to look well on the shelves; they were not merely prestige objects to be owned for the sake of display. He read them, and annotated their margins in his own hand. In his Aristotle, he annotated a huge amount; in his Plato, little. Often he copied the remarks of others, but he certainly made contributions of his own too, albeit none of great importance (and his attempts at the correction of texts have generally been regretted by later scholars). He explained, commended, criticised, got angry: carried on a dialogue with the authors.

He did a great deal of this in his Elements. Evidently he wrote in commentary from other copies of the book, including fragments from ancient geometers and other accretions, some of them illustrated with their own diagrams. But about fifty of his additions appear in no other surviving copy of the Elements, and may well be Arethas’ own work. He corrected the scribe, added comments, or made brief remarks like ‘nice’, ‘note’, or just inserted a tiny ornament. On one page he added a comment about the addition and subtraction of fractions, which originated from a lecture by Leo the geometer. Near the start and end of the volume he wrote two epigrams about Euclid.