The Book of Wonders

Later reports show that Latin scholars in centres such as Toledo employed the help of local experts: there would be a text in Arabic, a local person who spoke both Arabic and Spanish, and a visiting or immigrant scholar who could understand Spanish and write Latin. Translation would be effectively a two-stage process, with the text passing through a spoken Spanish version along the way, and much of the intellectual work of understanding the text done by the arabophone ‘assistant’ rather than the Latin ‘scholar’.

It is quite conceivable that Adelard had an assistant, now lost to history, or something of this kind: or perhaps someone who helped him to render the Arabic directly into Latin. Indeed, it seems less than plausible that he made his way through the conceptual and terminological complexity of the Arabic Elements without some such help. At one stage, the learned circle in Hereford and Malvern had included Petrus Alfonsi from Huesca in Aragon, a converted Spanish Jew who became physician to King Henry. He worked on astronomical material, and may well have provided the base translation from which Adelard produced his version of the tables of al-Khwarizmi. Petrus moved to France too early, it seems, to have worked on Adelard’s Elements, but his example indicates the kind of collaboration that might have been involved, and the kind of person who may have stood, uncredited, behind Adelard’s work.

Be that as it may, the Latin Elements was a remarkable production. It clearly showed the linguistic stages it had been through, and the struggles of this first medieval translator to find the right Latin words for what he needed to say. In one place Adelard tried three different phrases in succession, all trying to express the idea of ‘a ratio repeated three times’. Elsewhere he hesitated between words meaning ‘difference’ or ‘remainder’ when talking about the result of taking a quantity away from another.

It is plain to see that he was not working from the Greek text. He used none of the Greek loan-words that would later become common in Latin, such as hypotenusa, parallelogrammum, ysosceles. Instead his Latin contained a wealth of terms that were simply Arabic: alkamud (perpendicular), alkaida (base), mutekefia (proportional), elmugecem (solid), elmugmez (pentagon). Even when he knew the equivalent Latin words, Adelard sometimes deliberately adopted an Arabic terminology: elkora for sphere and elmukaab for cube, for instance.

Also from Adelard’s Arabic source came the names for some of the propositions, of which he made some strange gibberish: elefuga, dulcarnon, thenep atoz, seqqlebiz. Some of them nevertheless stuck, notably dulcarnon, which went on to be mentioned by Chaucer and would later facilitate the popular pun ‘dull carnon’. He also took from the Arabic Elements a curious habit of introducing the different parts of each proposition with fixed, formal phrases: Now we must prove … So I say that … For the sake of argument … The reason why. These do not appear in any surviving Greek version, and were surely not invented by Adelard; they provide a glimpse of features of his Arabic source which are otherwise lost.

Of the two main Arabic versions of the Elements, the modern consensus is that Adelard’s version seems to be derived from the earlier, that of al-Hajjaj. The clearest piece of evidence is that the number of propositions in Adelard’s Euclid agrees with al-Hajjaj in ten of the fifteen books, whereas in four of those books the later Arabic version, by Thabit, has a different number of propositions. Similarities of wording support the conclusion, but several matters complicate it. Al-Hajjaj’s version is largely lost; Adelard’s survives only incompletely (book 9 and part of book 10 have been lost). No surviving Arabic manuscript is close enough to Adelard’s version to have been his actual source, and it is possible that what he worked from was not a ‘pure’ al-Hajjaj text but one with some modifications. For further intrigue, a fifteenth- or sixteenth-century manuscript containing much of book 1 in Syriac agrees almost word for word with Adelard; even the lettering on the diagrams matches. Does this mean that the Syriac translator and Adelard used the same, Arabic source, now lost? Certainly the last word has not yet been written on the subject.

Adelard’s was a remarkable achievement, and his name became celebrated, attached to Euclidean material by later scribes whether it was really his or not. His opinions on some details in the arithmetic of Boethius were carefully recorded by a student; one ‘Ocreatus’ dedicated an arithmetical work to him. His version of the Elements was a key moment when a mathematical tradition from the shores of the Mediterranean acquired a presence in northern Europe, from there to pass – a few generations later – into the chain of new universities stretching from Italy to England.

By about 1150 Adelard was dead, but the translation work of the twelfth-century scholars went on, and Latin attention to the Elements of Euclid gathered pace. The translators of the period worked with evident excitement on a mass of material to which their access was somewhat haphazard, and they worked in some isolation from one another. Texts were translated more than once, and tangles of different versions emerged as new Arabic texts were obtained or new ways were tried of amalgamating them. For the Elements alone, the cast of characters becomes quite large and the names of the translators and editors give a sense of the range of people interested in the book: Hermann of Carinthia, Robert of Chester, Gerard of Cremona, Ioannes of Tinemue. Gerard, in the mid-twelfth century, actually moved to Toledo, becoming the century’s most prolific translator from Arabic: he rendered Euclidean commentaries and Euclid’s Data as well as the Elements. In Sicily, where there was a tradition of bilingualism and trilingualism, someone translated the Elements directly from Greek into Latin, late in the twelfth century. A number of other reworkings have not yet been studied in full even today: some of them exist only in single manuscripts and represent complex mixtures of different versions.

Thus all of the early versions, including Adelard’s own, came to be eclipsed. First by the version of Robert of Chester, popular throughout the twelfth century and, ironically, often attributed in the manuscripts to Adelard himself (Robert may have been a student of Adelard, which does something to explain the confusion). And, second, by the work of Campanus of Novara. Writing in the 1250s, he put together what would become the Latin Euclid of the later Middle Ages. He used Robert’s version for the statements of each proposition: material that – much of it – went back to Adelard. But he composed new versions of the proofs, bringing together material from other versions and commentaries. And he added to the book, with new propositions and definitions from various sources: the impulse to modify and improve the Elements was proving as durable as the book itself.

A hundred manuscripts of Campanus’ Elements survive today: it was a bestseller in its day. For Adelard’s version there are just four, none of them complete. But through Campanus, much of what Adelard had done in rendering Euclid’s words into Latin survived and flourished for another three centuries, and passed on into the era of print.

Erhard Ratdolt

Printing the Elements

May 1482, in La Serenissima: the Republic of Venice. The print shop of Erhard Ratdolt.

In one room, compositors perch on high stools, slotting tiny pieces of lead type into little frames, called composing sticks. A stick holds a few lines of text (upside down and backwards), and when it is full the assembled letters are lifted out in a block, and added into the tray – the forme – in which a whole sheet of text is being assembled. A good compositor can set a few thousand characters – several hundred words – in an hour.

Once a full sheet is made up, the letters (and any pictures) are clamped together and carried into the next room, to the press itself. Out slides the bed from under the press, and the forme full of letters is placed on it and spread with ink. Two frames fold out to hold the paper; they fold back and the whole thing – paper, ink, letters – slides back under the press. Two pressmen pull a long lever to screw the press down, pushing the paper against the inked type and transferring ink onto the paper. They release the lever, slide out and unfold the frames and take out the paper. The printer’s boy (or ‘devil’) takes it away. Another sheet of paper follows, and another: hour after hour.

The workshop is busy, noisy and dangerous. The type is made of lead; the ink probably contains vitriol, and its manufacture involves burning pitch and boiling oil. The press itself is heavy and as powerful as a wine press, its close ancestor.

From one workshop in the first months of 1482 there come more copies of Euclid’s Elements than Europe has made in 1,000 years.

The owner and overseer of that workshop, Erhard Ratdolt, was part of the German diaspora that took Gutenberg’s invention across Europe in the second half of the fifteenth century. One printing press in the world used movable type in the 1450s; by 1470 such machines existed in fourteen cities, and by 1480 in over a hundred. Born in about 1447, Ratdolt grew up in Augsburg in southern Germany, and after an apprenticeship crossed the Alps by the Brenner Pass, setting up as a printer in the first and finest city he reached: La Serenissima.

Venice in the 1470s.

Werner Rolevinck, Fasciculum temporum (Venice, 1485), fol. 37v. (Digital Library@Villanova University, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-SA 4.0)

A commercial and business hub with a fine natural harbour, Venice was at the height of its power and influence in the late fifteenth century: and of its splendour. In the previous half-century many of its famous landmarks had been erected: the facade of the Doge’s Palace, the Ca’ d’Oro, San Giovanni e Paolo, the Porta della Carta and the Ca’ Foscari. Giovanni Mocenigo occupied the doge’s throne. A French ambassador described the city:

I was conducted through the longest street, which they call the Grand Canal, and it is so wide that galleys frequently cross one another; indeed I have seen vessels of four hundred tons or more lie at anchor just by the houses. It is the fairest and best-built street, I think, in the world, and goes quite through the city. The houses are very large and lofty, and built of stone; the old ones are all painted; those of about a hundred years’ standing are faced with white marble from Istria, about one hundred miles off, and inlaid with porphyry and serpentine. Within they have, most of them, at least two chambers with gilt ceilings, rich chimney pieces, bedsteads of gold colour, their portals of the same, and exceedingly well furnished. In short, it is the most glorious city that I have ever seen, the most respectful to all ambassadors and strangers, governed with the greatest wisdom, and serving God with the most solemnity.

By 1476 Ratdolt was printing as a member of a three-man partnership, part of an immense expansion of print in the city: from nothing in 1469 to 150 print shops by the end of the century. The combination of convenient sources of paper in northern Italy and generous provision for the protection of texts and technical improvements made the city one of the centres for the new technology. Ratdolt and his partners printed calendars, histories and geographies, a total of eleven books in three years. They were some of the finest printed books ever produced, with ornamental title pages, careful woodcut illustrations, page borders and initial letters, and two-colour texts printed in black and red. Illustrations of eclipses in the calendars had colouring in yellow added by hand. The type, like that of other printers in Venice, was modelled on the handwriting of contemporary scholars; it is admired to this day for its harmony and elegance.

In 1478 the plague threatened to end it all. It afflicted Venice for four years, and at its height 1,500 people were dying every day. Many fled; half the printing houses closed, and Ratdolt’s partnership never printed again, although all three of its members survived. Ratdolt’s daughter Anna was born in June 1479 when the disaster was at its height.

By the following year he was beginning to rebuild his printing business, this time as sole owner and employer of a full team of compositors, pressmen, engravers, proofreaders, apprentices and assistants. He worked, not surprisingly in the circumstances, with a furious energy. In his first year on his own he produced eight books, and he took pains to reach a broad market, ranging across ecclesiastical works, histories and – a growing specialism of his – mathematical texts.

There had been plans to print the Elements before: the astronomer and printer Regiomontanus, under whom Ratdolt had served as apprentice, had proposed an edition in the 1470s but never carried it out. It fell to Ratdolt, then: and at his hands, ten years before Columbus crossed the Atlantic, Euclid made the momentous transition to print.

It was a vast project. Ratdolt chose the large ‘folio’ format, producing a book about eight inches by seven, and even so it filled 276 pages; nearly seventy sheets of paper had to go under the press, twice each, to produce each copy (each was then folded, so that when bound into the book it formed four pages). The compositors must have set well over half a million characters of type in all.

There were some problems no one would have expected. So many of Euclid’s propositions began with ‘If …’ (‘Si …’) or ‘Let there be …’ (‘Sit …’) that some pages needed up to thirteen decorated S’s: the set of decorated initials Ratdolt was using ran out and had to be supplemented by another set that did not match. In a similar way, the incessant reference to points in diagrams labelled A, B, C, D and so on, put pressure on the supply even of normal-sized capital letters. Four different sets of type had to be used in order to complete the book.

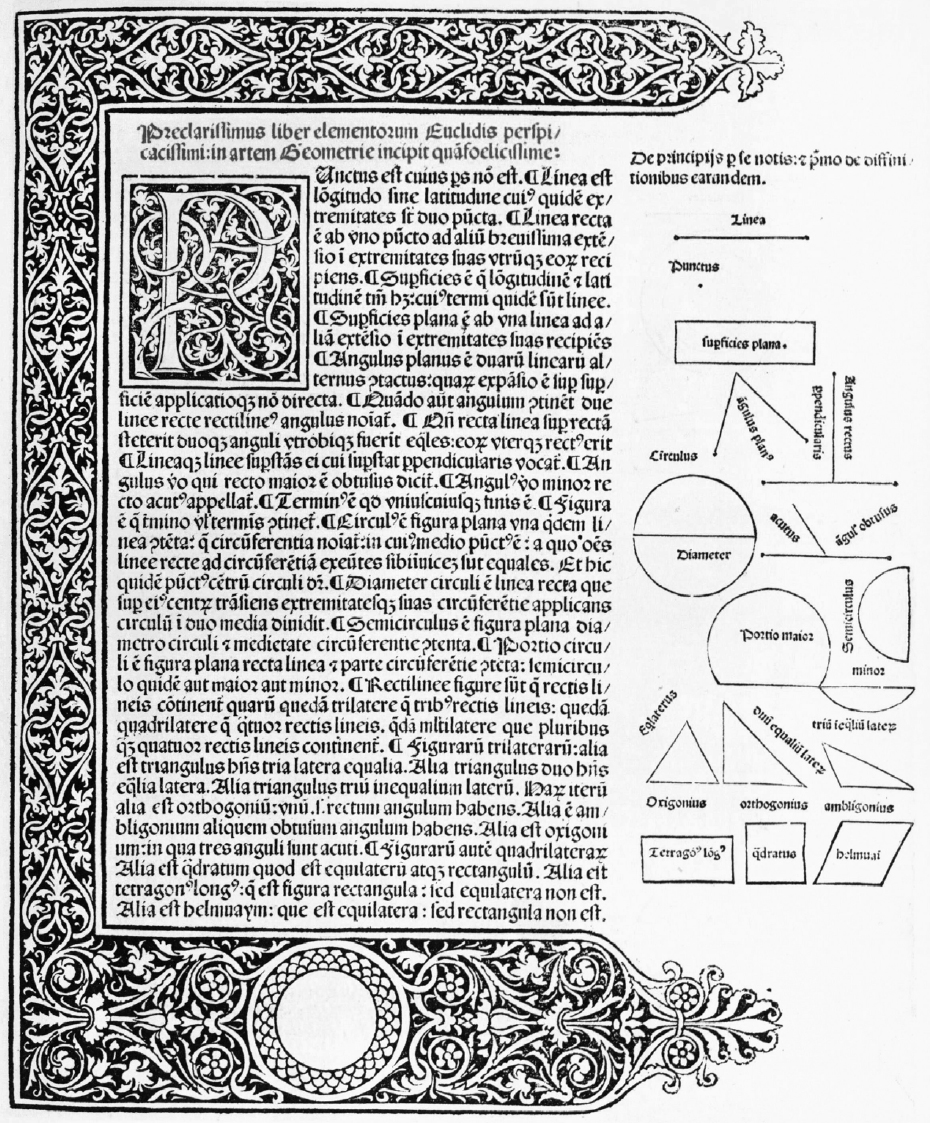

Technical challenges apart, Ratdolt took every care to make sure the book was of the highest quality. He seems to have obtained quite a good manuscript of the Elements, in Campanus’ Latin version: probably part of a celebrated ecclesiastical library deriving from the mid-century papal court, where there was a tradition of well-illustrated mathematical books. The decorated first page was put under the press three times: once for the text, once for the border and once for the title, which was printed in red. Pinholes in the paper were used to line up the separate layers of printing. The type was neat and strikingly accurate, and the decorated border – reused from one of Ratdolt’s earlier books – was a beautiful piece of design. The page layout was broadly similar to that of Gutenberg’s Bibles, with broad margins modelled ultimately on the layouts of fine medieval manuscripts.

And the diagrams? This was the first really geometrical book to be printed; the first for which a large number of accurate diagrams were needed. Printing diagrams was known to be hard; editions of Ptolemy and Vitruvius were appearing from other presses without diagrams, because they were too difficult to produce. And even in the world of manuscript, it had become common for diagrams to be poorly copied or even omitted because of the time and skill involved in their construction. The Elements needed 500 or more, and, as Ratdolt himself pointed out, nothing in geometry could be properly understood without them.

He was determined to get this right, and indeed his decision to print Euclid’s Elements seems to have depended on a breakthrough he achieved in the technique of printing geometrical diagrams. The usual way to insert illustrations in printed books was to carve them in relief in wood, clamping the block of wood into the frame with the type, inking it and printing from it in just the same way as the text. Good effects could be achieved, but there were limitations: particularly in creating fine lines of even thickness, keeping them straight when they were meant to be straight and circular when they were meant to be circular. It was particularly hard to make it work for geometrical diagrams.

Ratdolt boasted in a preface to his Elements that he had a special technique for printing the diagrams, but scholars do not agree about what it was. One suggestion is that he took strips of metal – zinc or copper most likely – bent them into the shapes required, and mounted them in plaster to hold them in place, together with pieces of type that would provide the labels – A, B, C, and so on – within the diagram. Another possibility is that he used cast pieces of metal clamped together much like the pieces of type that made up the words on the page. Or, again, he may have had special tools and techniques for making woodcuts of exceptionally fine quality.

In any case, the wooden or metal diagram could then be clamped into the set-up page of type – Ratdolt invariably placed the diagrams in the margin, which would simplify this part of the process – and its protruding edges inked and printed from just like the rest of the page. However it was done, Ratdolt achieved results of the highest quality, with fine, even lines that were curved or straight as required. He has deservedly been called the most inventive printer after Gutenberg. The result was a book of which Ratdolt could justly be proud, and which increased still further his already high reputation among Venetian printers. No surviving medieval manuscript of the Elements, in any language, has diagrams of a similar number and quality.

After a large number of copies had been printed, Ratdolt stopped his press and reset the first nine leaves of the book. He wanted to rearrange some of the diagrams, insert some new ones and generally improve the completeness and clarity of the pages. Such an obsessive care, a commitment to perfection, almost defies belief, even in the proud, skilled world of the early printers.

The Elements in 1482.

Preclarissimus liber elementorum Euclidis perspicacissimi (Venice, 1482), fol. 2r. (Wikimedia Commons/public domain)

It was a work fit for a king, and Ratdolt added to his book a separately printed leaf dedicating it to the doge. There’s no evidence that the doge actually commissioned or paid for the printing of the book (or wanted it), but Ratdolt’s dedicatory letter placed it unambiguously under his ruler’s protection, casting Giovanni Mocenigo in the role of patron and himself, Ratdolt, in the role of a creator offering up his work. It was a way to boost his own status – higher than a craftsman’s, and nearly as high as an author’s – as well as an opportunity to display to the world what he could do. For a few presentation copies, he printed on vellum instead of paper, and put gold dust into the ink instead of the usual lamp-black, so as to print the dedicatory letter in flamboyant gold letters. For the doge’s own copy, the first page was illuminated by hand to complete the effect.

The dedicatory letter itself spared no pains to emphasise Ratdolt’s own cleverness:

I used to wonder why it is that in your powerful and famous city there are many works of ancient and modern authors being published, but none or few and of little importance are books of mathematics … Until now, no one has found a way to make the geometric diagrams … I applied myself and with great effort I made the figures, so that the geometric figures are printed with the same ease as the verbal parts of the Elements.

Ratdolt probably printed over 1,000 copies of his remarkable edition of the Elements. He had set standards for mathematical typography as well as for the printing of geometrical diagrams; he had established a visual language for geometry within the new world of print, similar to the visual language of manuscript geometry but in subtle ways different.

There is sadly little information about where the copies went. A de luxe book is not necessarily a book that is read, although in the intellectual climate of fifteenth-century Italy it is reasonable to suppose that this, the first printed version of such a widely known ancient text, received its fair share of attention. And indeed, the surviving copies show that many a reader responded to the diagrams by working with pen or pencil in hand, re-copying them as the anonymous reader at Elephantine had done and using the blank space in Ratdolt’s generous margins as rough paper: continuing the ancient tradition of understanding and learning the ideas the words and diagrams embodied.

Before the century was out, there were a handful more editions of the Elements in a Latin abridgement, as well as a pirated reprint of Ratdolt’s edition that appeared at Vicenza in 1491. But the Elements really took flight during the next century, as print spread and cheapened and printed books decisively took over from manuscripts in many (though not all) situations. About forty substantially different versions of the Elements were produced between 1500 and 1600: some were printed several times; thus there was a new printing something like once a year on average. Most were in Latin, but Simon Grynäus edited the Greek text for publication in Basel in 1533, using manuscripts in Venice, Paris and Oxford. The first complete vernacular version to see print was the Italian translation by mathematician Niccolò Tartaglia, printed in 1543. By the end of the century the Elements would also be printed in German, French, Spanish, English and Arabic. It is not clear that any text except the Bible was being set up in type more frequently; that pattern would last another two centuries and more.

Ratdolt himself returned to his native Augsburg after ten brilliant years in Venice, there to print for another four decades. He developed a focus on liturgical books, though he also continued to work on scientific texts and histories. He didn’t use his novel system for printing geometrical diagrams again, and although he reprinted a number of his Venetian books, the Elements was not one of them.

Erhard Ratdolt died, wealthy and highly respected, in March 1528, at about the age of eighty-one. A tribute written by a fellow Venetian printer in 1482 – the year of his Elements – might stand as his epitaph:

The seven arts, abilities granted by the divine power, are amply bestowed on this German from Augsburg, Erhard Ratdolt, who is without peer as a master at composing type and printing books. May he enjoy fame, ever with the favour of the Sister Fates. Many satisfied readers can confirm this wish.

Marget Seymer her hand

Owning the Elements

A handwritten inscription in a 1543 printed edition of Euclid’s Elements, now in the National Library of Wales: ‘Marget Seymer her hand’.

Putting the Elements into print sent it into the wild, making it common property in a way it had never been before. Printed editions varied very widely, and reflected not just the range of medieval versions of the text but also the new agendas of the Renaissance world, and the commercial imperatives of its printers and publishers.