полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

There is no doubt also that there is a great similarity between the two, in the attitude and inclination of the body, the position of the feet, the style of dress, and even the lines of the folds. But portrait-statues of bronze may belong to any age; because, while the sculptor in marble is obliged to produce a work of his own hands and conception, and the date of a marble statue can therefore be determined by comparison with other well-known works, the caster in bronze can easily reproduce specimens of earlier and better times by taking a mould from a good original, altering the features slightly, and then casting it in excellent bronze. This seems to be the case with this celebrated image. I know that the current opinion makes it contemporary with the erection of Constantine's basilica; but to this I cannot subscribe on account of the comparatively modern shape of the keys. One of two things must be true,—either that these keys are a comparatively recent addition, in which case the statue may be a work of the fourth century, or they were cast together with the figure. If the latter be the fact the statue is of a comparatively recent age. Doubts on the subject might be dispelled by a careful examination of these crucial details, which I have not been able to undertake to my satisfaction.

Bronze Statue of S. Peter.

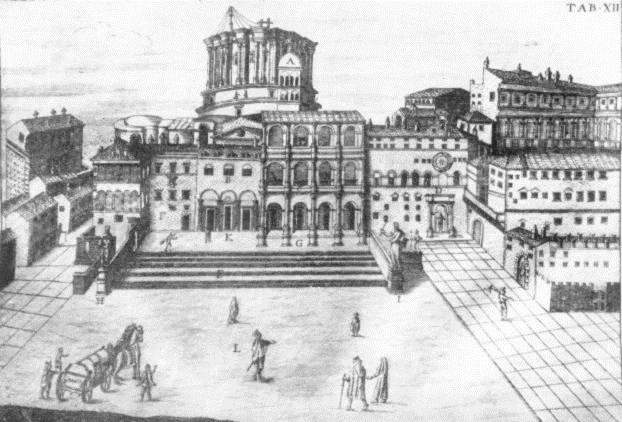

The destruction of old S. Peter's is one of the saddest events in the history of the ruin of Rome. It was done at two periods and in two sections, a cross wall being raised in the mean time in the middle of the church to allow divine service to proceed without interruption, while the destruction and the rebuilding of each half was accomplished in successive stages.

Statue of S. Hippolytus.

The work began April 18, 1506, under Julius II. It took exactly one century to finish the western section, from the partition wall to the apse. The demolition of the eastern section began February 21, 1606. Nine years later, on Palm Sunday, April 12, 1615, the jubilant multitudes witnessed the disappearance of the partition wall, and beheld for the first time the new temple in all its glory.

It seems that Paul V., Borghese, to whom the completion of the great work is due, could not help feeling a pang of remorse in wiping out forever the remains of the Constantinian basilica. He wanted the sacred college to share the responsibility for the deed, and summoned a consistory for September 26, 1605, to lay the case before the cardinals. The report revealed a remarkable state of things. It seems that while the foundations of the right side of the church built by Constantine had firmly withstood the weight and strain imposed upon them, the foundation of the left side, that is, the three walls of the circus of Caligula, which had been built for a different purpose, had yielded to the pressure so that the whole church, with its four rows of columns, was bending sideways from right to left, to the extent of three feet seven inches. The report stated that this inclination could be noticed from the fact that the frescoes of the left wall were covered with a thick layer of dust; it also stated that the ends of the great beams supporting the roof were all rotten and no longer capable of bearing their burden. Then cardinal Cosentino, the dean of the chapter, rose to say that, only a few days before, while mass was being said at the altar of S. Maria della Colonna, a heavy stone had fallen from the window above, and scattered the congregation. The vote of the sacred college was a foregone conclusion. The sentence of death was passed upon the last remains of old S. Peter's; a committee of eight cardinals was appointed to preside over the new building, and nine architects were invited to compete for the design. These were Giovanni and Domenico Fontana, Flaminio Ponzio, Carlo Maderno, Geronimo Rainaldi, Nicola Braconi da Como, Ottavio Turiano, Giovanni Antonio Dosio, and Ludovico Cigoli. The competition was won by Carlo Maderno, much to the regret of the Pope, who was manifestly in favor of his own architect, Flaminio Ponzio. The execution of the work was marked by an extraordinary accident. On Friday, August 27, 1610, a cloud-burst swept the city with such violence that the volume of water which accumulated on the terrace above the basilica, finding no outlet but the winding staircases which pierced the thickness of the walls, rushed down into the nave in roaring torrents and inundated it to a depth of several inches. The Confession and tomb of the apostle were saved only by the strength of the bronze door.

It is very interesting to follow the progress of the work in Grimaldi's diary, to witness with him the opening and destruction of every tomb worthy of note, and to make the inventory of its contents. The monuments were mostly pagan sarcophagi, or bath basins, cut in precious marbles; the bodies of Popes were wrapped in rich robes, and wore the "ring of the fisherman" on the forefinger. Innocent VIII., Giovanni Battista Cibo (1484-1492), was folded in an embroidered Persian cloth; Marcellus II., Cervini (1555), wore a golden mitre; Hadrian IV., Breakspeare (1154-1159), is described as an undersized man, wearing slippers of Turkish make, and a ring with a large emerald. Callixtus III. and Alexander VI., both of the Borgia family, have been twice disturbed in their common grave: the first time by Sixtus V., when he removed the obelisk from the spina of the circus to the piazza; the second by Paul V. on Saturday, January 30, 1610, when their bodies were removed to the Spanish church of Montserrat, with the help of the marquis of Billena, ambassador of Philip III., and of cardinal Çapata.

Grimaldi asserts that Michelangelo's plan of a Greek cross had not only been designed on paper, but actually begun. When Pope Borghese and Carlo Maderno determined upon the Latin cross, not only the foundations of the front had been finished according to Michelangelo's design, but the front itself, with its coating of travertine, had been built to the height of several feet. The construction of the dome was begun on Friday, July 15, 1588, at 4 p. m. The first block of travertine was placed in situ at 8 p. m. of the thirtieth. The cylindrical portion or drum (tamburo) which supports the dome proper was finished at midnight of December 17, of the same year, a marvellous feat to have accomplished. The dome itself was begun five days later, and finished in seventeen months. If we remember that the experts of the age had estimated ten years as the time required to accomplish the work, and one million gold scudi as the cost, we wonder at the power of will of Sixtus V., who did it in two years and spent only one fifth of the stated sum.85 He foresaw that the political persecution from the crown of Spain and the daily assaults, almost brutal in their nature, which he had to endure from count d'Olivare, the Spanish ambassador, would shorten his days, and consequently manifested but one desire: that the dome and the other great works undertaken for the embellishment and sanitation of the city should be finished before his death. Six hundred skilled craftsmen were enlisted to push the work of the dome night and day; they were excused from attending divine service on feast days, Sundays excepted. We may form an idea of the haste felt by all concerned in the enterprise, and of their determination to sacrifice all other interests to speed, by the following anecdote. The masons, being once in need of another receptacle for water, laid their hands on the tomb of Pope Urban VI., dragged the marble sarcophagus under the dome on the edge of a lime-pit, and emptied it of its contents. The golden ring was given to Giacomo della Porta, the architect, the bones were put aside in a corner of the building, and the coffin was used as a tank from 1588 to 1615.

S. PETER'S IN 1588. (From an engraving by Ciampini)

When we consider that the building-materials—stones, bricks, timber, cement, and water—had to be lifted to a height of four hundred feet, it is no wonder that five hundred thousand pounds of rope should have been consumed, and fifteen tons of iron. The dome was built on a framework of most ingenious design, resting on the cornice of the drum so lightly that it seemed suspended in mid air. One thousand two hundred large beams were employed in it.

Fea and Winckelmann assert that the lead sheets which cover the dome must be renewed eight or ten times in a century. Winckelmann attributes their rapid decay to the corrosive action of the sirocco wind; Fea to the variations in temperature, which cause the lead to melt in summer, and crack in winter.

The size and height, the number of columns, altars, statues, and pictures,—in short, the mirabilia of S. Peter's,—have been greatly exaggerated. There is no necessity of exaggeration when the truth is in itself so astonishing. Readers fond of statistics may consult the works of Briccolani and Visconti.86 The basilica is approached by a square 1256 feet in diameter. The nave is six hundred and thirteen feet long, eighty-eight wide, one hundred and thirty-three high; the transept is four hundred and forty-nine feet long. The cornice and the mosaic inscription of the frieze are 1943 feet long. The dome towers to the height of four hundred and forty-eight feet above the pavement, with a diameter on the interior of 139.9 feet, a trifle less than that of the Pantheon. The letters on the frieze are four feet eight inches high. The old church contained sixty-eight altars and two hundred and sixty-eight columns; while the modern one contains forty-six altars,—before which one hundred and twenty-one lamps are burning day and night,—and seven hundred and forty-eight columns, of marble, stone and bronze. The statues number three hundred and eighty-six, the windows two hundred and ninety.

It is easy to imagine to what surprising effects of light and shade such vastness of proportion lends itself on the occasion of illuminations. These were made both inside (Holy Thursday and Good Friday) and outside (Easter, and June 29). The outside illumination required the use of forty-four hundred lanterns, and of seven hundred and ninety-one torches, and the help of three hundred and sixty-five men. It has not been seen since 1870. I have heard from old friends who remember the illumination of the interior, which was given up more than half a century ago, that no sight could be more impressive. In the darkness of the night, a cross studded with thirteen hundred and eighty lights shone like a meteor at a prodigious height, while the multitude crowding the church knelt and prayed in silent rapture.

Before leaving the Vatican let me answer a doubt which may naturally have occurred to the mind of the reader, as it has long perplexed the author. After the many vicissitudes to which the place has been subject, from the time of Elagabalus to the pillage of the constable de Bourbon, can we be sure that the body of the founder of the Roman Church is still lying in its grave under the great dome of Michelangelo, under the canopy of Urban VIII., under the high altar of Clement VIII.? After considering the case from its various aspects, and weighing all the circumstances which have attended each of the barbaric invasions, I cannot see any reason why we should disbelieve the popular opinion. The tombs of S. Peter and S. Paul have been exposed but once to imminent danger, and that happened in 846, when the Saracens took possession of their respective churches and plundered them at leisure. Suppose the crusaders had taken possession of Mecca: their first impulse would have been to wipe the tomb of the Prophet from the face of the earth, unless the keepers of the Kaabah, warned of their approach, had time to conceal or protect the grave by one means or another. Unfortunately, we know very little about the Saracenic invasion of 846; still it seems certain that Pope Sergius II. and the Romans were warned days or weeks beforehand of the landing of the infidels, by a despatch from the island of Corsica. Inasmuch as the churches of S. Peter and S. Paul were absolutely defenceless, in their outlying positions, I am sure that steps were taken to conceal or wall in the entrance to the crypts and the crypts themselves, unless the tombs were removed bodily to shelter within the city walls. An argument, very little known but of great value, seems to prove that the relics were saved.

The "Liber Pontificalis" describes, among the gifts of Constantine, a cross of pure gold, weighing one hundred and fifty pounds, which he placed over the gold lid of the coffin. The golden cross bore the following inscription in niello work, "Constantine the emperor and Helena the empress have richly decorated this royal crypt, and the basilica which shelters it." If this precious object is there, the remains must a fortiori be there also. Here comes the decisive test. In the spring of 1594, while Giacomo della Porta was levelling the floor of the church above the Confession, removing at the same time the foundations of the Ciborium of Julius II., the ground gave way, and he saw through the opening what nobody had beheld since the time of Sergius II.,—the grave of S. Peter,—and upon it the golden cross of Constantine. On hearing of the discovery, Pope Clement VIII., accompanied by cardinals Bellarmino, Antoniano, and Sfrondato, descended to the Confession, and with the help of a torch, which Giacomo della Porta had lowered into the hollow space below, could see with his own eyes and could show to his followers the cross, inscribed with the names of Constantine and Helena. The impression produced upon the Pope by this wonderful sight was so great that he caused the opening to be closed at once. The event is attested not only by a manuscript deposition of Torrigio, but also by the present aspect of the place. The materials with which Clement VIII. sealed the opening, and rendered the tomb once more invisible and inaccessible, can still be seen through the "cataract" below the altar.

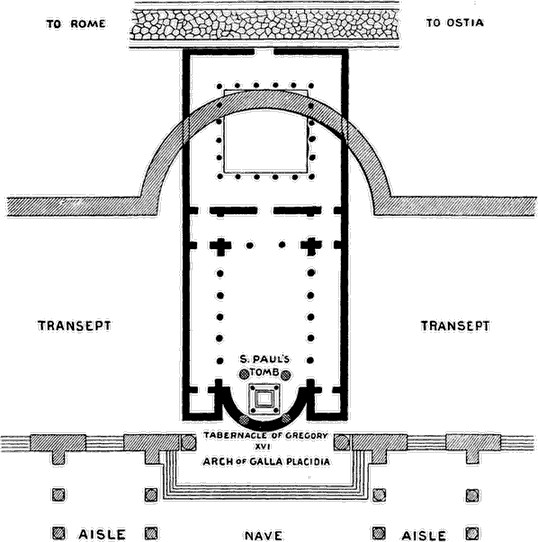

THE TWO BASILICAS OF S. PAUL

The original structure of Constantine in black, that of Theodosius and Honorius shaded

Wonder has been manifested at the behavior of Constantine towards S. Paul, whose basilica at the second milestone of the Via Ostiensis appears like a pigmy structure in comparison to that of S. Peter. Constantine had no intention of placing S. Paul in an inferior rank, or of showing less honor to his memory. He was compelled by local circumstances to raise a much smaller building to this apostle. As before stated, there were three rules which builders of sacred memorial edifices had to observe: first, that the tomb-altar of the saint in whose honor the building was to be erected should not be molested or moved from its original place either vertically or horizontally; second, that the edifice should be adapted to the tomb so as to give it a place of honor in the centre of the apse; third, that the apse and the front of the edifice should look towards the east. The position of S. Peter's tomb in relation to the circus of Nero and the cliffs of the Vatican was such as to give the builders of the basilica perfect freedom to extend it in all directions, especially lengthwise. This was not the case with that of S. Paul, which was only a hundred feet distant from an obstacle which could not be overcome,—the high-road to Ostia, the channel by which the city of Rome was fed. The road to Ostia ran east of the grave; hence the necessity of limiting the size of the church within these two points. Discoveries made in 1834, when the foundations of the present apse were strengthened, and again in 1850, when the foundations of the baldacchino of Pius IX. were laid,87 have enabled Signor Paolo Belloni, the architect, to reconstruct the plan of the original building of Constantine. His memoir88 is full of useful information well illustrated. One of his illustrations, representing the comparative plans of the original and modern churches, is here reproduced.

The plan needs no comment, but one particular cannot be omitted. In the course of the excavations for the baldacchino, the remains of classical columbaria were found a few feet from the grave of the apostle, with their inscriptions still in place. He must, therefore, have been buried, like S. Peter, in a private area, surrounded by pagan tombs.

In 386 Valentinian, Theodosius, and Arcadius asked Flavius Sallustius, prefect of the city, to submit to the Senate and the people a scheme for the reconstruction a fundamentis of the basilica, so as to make it equal in size and beauty to that of the Vatican. To fulfil this project, without disturbing either the grave of the apostle or the road to Ostia, there was but one thing to do; this was to change the orientation of the church from east to west, and extend it at pleasure towards the bank of the Tiber. The consent of the S. P. Q. R. was easily obtained, and the magnificent temple, which lasted until the fire of July 15, 1823, was thus raised so as to face in a direction opposite to the usual one.

The Burning of S. Paul's, July 15, 1823. (From an old print.)

The name of Pope Siricius, who was then governing the church, can still be seen engraved on one of the columns, formerly in the left aisle, now in the north vestibule:—

SIRICIVS EPISCOPVS Α

Another rare monument of historical value, in spite of its humble origin, came to light at the beginning of the last century, and was published by Bianchini and Muratori, who failed, however, to explain its meaning. It is a brass label once tied to a dog's collar, with the inscription "[I belong] to the basilica of Paul the apostle, rebuilt by our three sovereigns [Valentinianus, Theodosius, and Arcadius]. I am in charge of Felicissimus the shepherd." Such inscriptions were engraved on the collars of dogs, and slaves, so that in case they ran away from their masters, their legal ownership would be known at once by the police, or whoever chanced to catch them.

In course of time the basilica became the centre of a considerable group of buildings, especially of monasteries and convents. There were also chapels, baths, fountains, hostelries, porticoes, cemeteries, orchards, farmhouses, stables, and mills. This small suburban city was exposed to a constant danger of pillage, on account of its location on the high-road from the coast. In 846 it was ransacked by the Saracens, before the Romans could come to the rescue. For these considerations, Pope John VIII. (872-882) determined to put the church of S. Paul and its surroundings under shelter, and to raise a fort that could also command the approach to Rome from this most dangerous side.

The construction of Johannipolis, by which the history of the classical and early mediæval fortifications of Rome is brought to a close, is described by one document only: an inscription above the gate of the castle, which was copied first by Cola di Rienzo, and later by Pietro Sabino, professor of rhetoric in the Roman archigymnasium (Sapienza), towards the end of the fifteenth century. A few fragments of this remarkable document are still preserved in the cloister of the monastery. It states that Pope John VIII. raised a wall for the defence of the basilica of S. Paul's and the surrounding churches, convents, and hospices, in imitation of that built by Leo IV. for the protection of the Vatican suburb. The determination to fortify the sacred buildings at the second milestone of the Via Ostiensis was taken, as I have just said, in consequence of the inroads of the Saracens, which, under the pontificate of John, had become so frequent. The atrocities which marked their second landing on the Roman coast were so appalling that the whole of Europe was shaken with terror. Having failed in his attempt to secure help from Charles the Bald, John placed himself at the head of such scanty forces as he could gather from land and sea, under the pressure of events. Ships from several harbors in the Mediterranean met in the roads of Ostia; and on hearing that the hostile fleet had sailed from the bay of Naples, the Pope set sail at once. The gallant little squadron confronted the infidels under the cliffs of Cape Circeo, and inflicted upon them such a bloody defeat that the danger was averted, at least for a time. The church galleys came back to the mouth of the Tiber, laden with a considerable booty.

It seems that the advance fort of Johannipolis was finished and consecrated by Pope John soon after the naval battle of Cape Circeo (a. d. 877), because the inscription above referred to speaks of him as a triumphant leader,—SEDIS APOSTOLICÆ PAPA JOHANNES OVANS.

The location of this fortified outpost could not have been more judiciously selected. It commanded the roads from Ostia, Laurentum, and Ardea, those, namely, from which the pirates could most easily approach the city. It commanded also the water-way by the Tiber, and the towpaths on each of its banks. It is a great pity that no stone of this historical wall should be left standing. It saved the city from further invasions of the African pirates, as the agger of Servius Tullius had saved it, centuries before, from the attacks of the Carthaginians. I have examined the ground between S. Paul's, the Fosso di Grotta Perfetta, the Vigna de Merode, at the back of the apse, and the banks of the river, without finding a trace of the fortification. I believe, however, that the wall which encloses the garden of the monastery on the south side runs on the same line with John's defences, and rests on their foundations. We must not wonder at the disappearance of Johannipolis, when we have proofs that even the quadri-portico, by which the basilica was entered from the riverside, has been allowed to disappear through the negligence and slovenliness of the monks. Pope Leo I. erected in the centre of the quadri-portico a fountain crowned by a Bacchic Kantharos, and wrote on its epistyle a brilliant epigram, inviting the faithful to purify themselves bodily and spiritually, before presenting themselves to the apostle within. When Cola di Rienzo visited the spot, towards the middle of the fourteenth century, the monument was still in good condition. He calls it "the vase of waters (cantharus aquarum), before the main entrance (of the church) of the blessed Paul." One century later the whole structure had become a heap of ruins. Fra Giocondo da Verona looked in vain for the inscription of Leo I.; he could only find a fragment "lying among the nettles and thorns" (inter orticas et spineta). The same indifference was shown towards the edifices by which the basilica was surrounded. They fell, or were overthrown, one by one.

In 1633, when Giovanni Severano wrote his book on the Seven Churches, only one bit of ruins could be identified, the door and apse of the church of S. Stephen, to which a powerful convent had once been attached. Stranger still is the total destruction of the portico, two thousand yards long, which connected the city gate—the Porta Ostiensis—with the basilica. This portico was supported by marble columns, one thousand at least, and its roof was covered with sheets of lead. Halfway between the gate and S. Paul's, it was intersected by a church, dedicated to an Egyptian martyr, S. Menna. The church of S. Menna, the portico, its thousand columns, even its foundation walls, have been totally destroyed. A document discovered by Armellini in the archives of the Vatican says that some faint traces of the building (vestigia et parietes) could be still recognized in the time of Urban VI. This is the last mention made by an eye-witness.

Here, also, we find the evidence of the gigantic work of destruction pursued for centuries by the Romans themselves, which we have been in the habit of attributing to the barbarians alone. The barbarians have their share of responsibility in causing the abandonment and the desolation of the Campagna; they may have looted and damaged some edifices, from which there was hope of a booty; they may have profaned churches and oratories erected over the tombs of martyrs; but the wholesale destruction, the obliteration of classical and mediæval monuments, is the work of the Romans and of their successive rulers. To them, more than to the barbarians, we owe the present condition of the Campagna, in the midst of which Rome remains like an oasis in a barren solitude.