полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

We have seen works of perhaps greater importance accomplished in our age; but, as Baron de Hübner remarks, in speaking of another great man, Sixtus V., they are the joint product of government, national credit, speculation, and public and private capital; and they are facilitated by wonderful mechanical contrivances. The transformation of Rome at the time of Augustus was the work of a few wealthy citizens, whose names will forever be connected with their splendid creations.

The gates of the Mausoleum of Augustus were opened for the last time in a. d. 98, for the reception of the ashes of Nerva. We hear no more of it until the year 410, when the Goths ransacked the imperial vaults. No harm, however, seems to have been done to the building itself at that time. Like the mausolea of Metella, on the Appian Way, and Hadrian, on the right bank of the Tiber, it was subsequently converted into a stronghold, and occupied by the Colonnas. Its ultimate destruction, in 1167, marks one of the great occurences in the history of mediæval Rome.

Between the counts of Tusculum, partisans of the German Empire, and the Romans, devoted to their independent municipal government, there was a feud of long standing, which had resulted occasionally in open violence. In 1167, Alexander III. being Pope, the Romans decided to strike the decisive blow on the Tusculans, as well as on their allies, the Albans. The cardinal of Aragona, the biographer of Alexander III., states that towards the end of May, when the cornfields begin to ripen, the Romans sallied forth on their expedition against Count Raynone, much against the Pope's will; and having crossed the frontier of his estate, set fire to the crops, uprooted trees and vineyards, ruined farmhouses, killed cattle, and laid siege to the city itself. Raynone, knowing how precarious his position was, implored the help of the emperor Frederic, who was at that time encamped near Ancona. The request was granted, and a body of German warriors returned with the ambassadors to the rescue of Tusculum. They soon perceived that, although the Romans had the advantage of numbers, they were so imperfectly drilled and so insubordinate that the chances were equal for both sides. The battle was opened at nine o'clock on the morning of Whit-Monday, May 30, 1167. The twelve hundred Germans, led by Christian, archbishop of Mayence, and three hundred Tusculans, led by Raynone, gallantly attacked the advance guard of the Roman army, which numbered thirty thousand men. Overcome by panic, the Romans fled and disbanded at the first encounter. They were closely followed from valley to valley, and slain in such numbers that scarcely one third of them reached the walls of Aurelian in safety. The local memories of the battle still survive, after a lapse of eight centuries; the valley which leads from the villa of Q. Voconius Pollio (Sassone) to Marino being still called by the peasantry "la valle dei morti."

On the following day an embassy was sent to Archbishop Christian and Count Raynone begging leave to bury the dead. The permission was granted, with the humiliating clause that the number of dead and missing should be reported at Tusculum. The legend says that the number ascertained was fifteen thousand, which is an exaggeration. Contemporary historians speak of only two thousand dead and three thousand prisoners, who were sent to Viterbo. The chronicle of Sikkardt adds that the Romans were encamped near Monte Porzio; that the battle lasted only two hours, and that the dead were buried in the church of S. Stefano, at the second milestone of the Via Latina, with the following inscription:—

MILLE DECEM DECIES ET SEX DECIES QVOQVE SENI,—which, if genuine, proves that the number of killed in battle was only eleven hundred and sixty-six, that is, 1,000+100+60+6.

The connection of the Mausoleum of Augustus with this mediæval battle of Cannæ is easily explained. The mausoleum had been selected by the Colonnas for their stronghold in the Campus Martius, and it was for their interest to keep it in good repair. As happens in cases of crushing defeats, when the succumbing party must find an excuse and an opportunity for revenge, the powerful Colonnas were accused of high treason, namely, of having led the advance-guard of the Romans into an ambush. Consequently they were banished from the city, and their castle on the Campus Martius was destroyed. Thus perished the Mausoleum of Augustus.

The history of its ruins, however, does not end with the events just described. Most important of all, they are associated with the fate of Cola di Rienzo. His biographer, in Book III. ch. xxiv., says that the body of the Tribune was allowed to remain unburied, for two days and one night, on some steps near S. Marcello. Giugurta and Sciarretta Colonna, leaders of the aristocratic faction, ordered the body to be dragged along the Via Flaminia, from S. Marcello to the mausoleum which had been occupied and fortified by that powerful family once more in 1241. In the mean time, the Jews had gathered in great numbers around the "Campo dell' Augusta," as the ruins were then called. Thistles and dry brushwood were collected and set afire, and the body thrown into the flames; this extemporized pyre being fed with fresh fuel until every particle of the corpse was consumed. A strange coincidence, that the same monument which the founder of the empire, the oppressor of Roman liberty, had chosen for his own burial-place, should serve, thirteen centuries later, for the cremation of him who tried to restore popular freedom! Here is the description of the event by a contemporary: "Along this street (the Corso of modern days) the corpse was dragged as far as the church of S. Marcello. There it was hung by the feet to a balcony, because the head had been crushed and lost, piece by piece, along the road; so many wounds had been inflicted on the body that it might be compared to a sieve (crivello); the entrails were protruding like a bull's in the butchery; he was horribly fat, and his skin white, like milk tinted with blood. Enormous was his fatness,—so great as to give him the appearance of an ox (bufalo). The body hung from the balcony at S. Marcello for two days and one night, while boys pelted it with stones. On the third day it was removed to the Campo dell' Augusta, where the Jewish colony, to a man, had congregated; and although the pyre had been made only with thistles, in which those ruins abounded, the fat from the corpse kept the flames alive until their work was accomplished. Not an atom of the great champion of the Romans was left."

I need not remind the reader that the house near the Ponte Rotto, and opposite the Temple of Fortuna Virilis, which guides attribute to Cola di Rienzo, has no connection with him.99 He was born and lived many years near the church of S. Tommaso in Capite Molarum, between the Palazzo Cenci and the synagogue of the Jews, on the left bank of the Tiber. The church is still in existence, although it has changed its mediæval name into that of S. Tommaso a' Cenci.

The house by the Ponte Rotto, just referred to, has still another name in folk-lore; it is called the House of Pilate. The denomination is not so absurd as it at first seems; it brings us back to bygone times, when passion-plays were performed in Rome in a more effective way than they are now exhibited at Oberammergau. They took place, not on a wooden stage, so suggestive of conventionality, but in a quarter of the city most wonderfully adapted to represent the Via Dolorosa of Jerusalem, from the houses of Pilate and Caiaphas to the summit of Calvary.

The passion-play began at a house, Via della Bocca della Verità, No. 37, which is still called the "Locanda della Gaiffa," a corruption of Gaifa, or Caiaphas. From this place the procession moved across the street to the "Casa di Pilato," as the house of Crescenzio was called, where the scenes of the Ecce Homo, the flagellation, and the crowning with thorns, were probably enacted. The Via Dolorosa corresponds to our streets of the Bocca della Verità, Salara, Marmorata, and Porta S. Paolo; there must have been stations at intervals for the representation of the various episodes, such as the meeting with the Virgin Mary, the fainting under the cross, the meeting with Veronica and with the man from Cyrene. The performance culminated on the summit of the Monte Testaccio, where three crosses were erected. One is still there.

Readers who have had an opportunity of studying the Via Dolorosa at Jerusalem will be struck by the resemblance between the original and its Roman imitation. The latter must have been planned by crusaders and pilgrims on their return from the Holy Land towards the end of the thirteenth century. Every particular, even those which rest on doubtful tradition, was repeated here, such as that referring to the house of the rich man, and to the stone in front of it on which Lazarus sat. A ruin half-way between the house of Pilate, by the Ponte Rotto, and the Monte Testaccio, or Calvary, is still called the Arco di S. Lazaro.

The Mausoleum of Augustus was explored archæologically for the first time in 1527, when the obelisk now in the Piazza di S. Maria Maggiore was found on the south side, near the church of S. Rocco. On July 14, 1519, Baldassarre Peruzzi discovered and copied some fragments of the original inscriptions in situ; but the discovery made in 1777 casts all that preceded it into the shade. In the spring of that year, while the corner house between the Corso and the Via degli Otto Cantoni (opposite the Via della Croce) was being built, the ustrinum, or sacred enclosure for the cremation of the members of the imperial family, came to light, lined with a profusion of historical monuments. Strabo describes the place as paved with marble, enclosed with brass railings, and shaded by poplars. The marble pavement was found at a depth of nineteen feet below the sidewalk of the Corso. The first object to appear was the beautiful vase of alabastro cotognino, now in the Vatican Museum (Galleria delle Statue), three feet in height, one and one half in diameter, with a cover ending in a lotus flower, the thickness of the marble being only one inch. The vase had once contained the ashes of one of the imperial personages in the mausoleum; either Alaric's barbarians or Roman plunderers must have left it in the ustrinum, after looting its contents.

The marble pedestals lining the borders of the square were of two kinds: some were intended to indicate the spot on which each prince had been cremated, others the place where the ashes had been deposited. The former end with the formula HIC CREMATVS (or CREMATA) EST, the latter with the words HIC SITVS (or SITA) EST.

Augustus was not the first member of the family to occupy the mausoleum. He was preceded by Marcellus (28 b. c.) whose premature fate is so admirably described by Virgil (Æneid, vi. 872); by Marcus Agrippa, in 14 b. c.; by Octavia, the sister of Augustus, in the year 13; by Drusus the elder, in the year 9; and by Caius and Lucius, nephews of Augustus. After Augustus, the interments of Livia, Germanicus, Drusus, son of Tiberius, Agrippina the elder, Tiberius, Antonia wife of Drusus, Claudius, Brittannicus, and Nerva are registered in succession. Of these great and, in many cases, admirable men and women, ten funeral cippi have been found in the ustrinum, some by the Colonnas before they were superseded by the Orsinis in the possession of the place, some in the excavations of 1777.

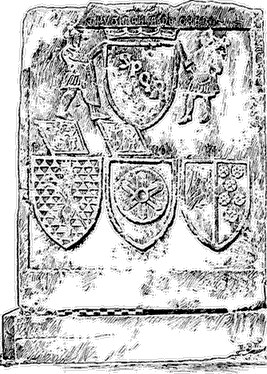

The fate of two of them cannot fail to impress the student of the history of the ruins of Rome. The pedestal of Agrippina the elder, daughter of Agrippa, wife of Germanicus, and mother of Caligula, and that of her eldest son Nero, were hollowed out during the Middle Ages, turned into standard measures for solids, and as such placed at the disposal of the public in the portico of the city hall. The pedestal of Nero perished during the renovation of the Conservatori Palace at the time of Michelangelo; that of Agrippina is still there.

The Cippus of Agrippina the Elder, made into a measure for grain.

The fate of this noble woman is described by Tacitus in the sixth book of the Annals; she was banished by Tiberius to the island of Pandataria, now called Ventotiene, where she spent the last three years of her life in solitude and grief. In 33 a. d.—the most memorable date in Christian chronology—she either starved herself to death voluntarily, or was starved by order of her persecutor. On hearing of her death the emperor eulogized his own clemency, because, instead of strangling the princess and exposing her body on the Gemonian steps, he had allowed her to die a peaceful death in that island. No honors were paid to her memory, but as soon as Caligula succeeded Tiberius in the government of the empire, he sailed to Pandataria, collected the ashes of his mother and relatives, and ultimately placed them in the mausoleum. The cippus represented in the illustration below is manifestly the work of Caligula, because mention is made on it of his accession to the throne. The hole excavated in it in the Middle Ages is capable of holding three hundred pounds of grain, as shown by the legend RVGIATELLA DE GRANO, engraved in Gothic letters above the municipal coat of arms. The three armorial shields below belong to the three syndics, or conservatori, by whose authority the standard measure was made. Another inscription, engraved in 1635 on the opposite side, says: "The S.P.Q.R. pay honor to the memory of the noble and courageous woman who voluntarily put an end to her life" (and here follows a witticism of doubtful taste on the bread which she denied herself, and on the breadstuffs, for the measurement of which her tomb had been used).

The other cippi found in the ustrinum mention four other children of Germanicus, among them Caius Cæsar, the lovely child who was so much beloved by Augustus, and so deeply regretted by him. A statue representing the youth with the attributes of a Cupid was dedicated by Livia in the temple of the Capitoline Venus, and another one was placed by Augustus in his own bedroom, on entering and leaving which he never missed kissing the cherished image.

The Mausoleum of Augustus and its precious contents have not escaped the spoliation and desecration which seem to be the rule both in past and modern times. The building is used now as a circus. Its basement is concealed by ignoble houses; the urn of Agrippina is kept in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori; three others have been destroyed, and six belong to the Vatican Museum.

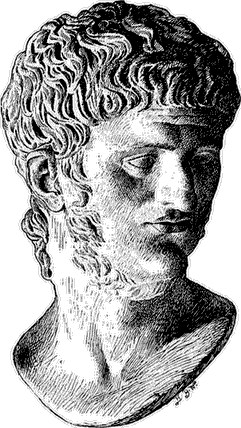

Head of Nero, in the Capitoline Museum.

The Tomb of Nero. The defection of the last Roman legion was announced to Nero while at dinner in the Golden House. On hearing the news, he tore up the letters, upset the table, dashed upon the floor two marvellous cups, called Homeric, because their chiselling represented scenes from the Iliad; and having borrowed from Locusta a phial of poison, went out to the Servilian gardens. He then despatched a few faithful servants to Ostia with orders to keep a squadron of swift vessels in readiness for his escape. After this he inquired of the officers of the prætorian guards if they were willing to accompany him in his flight; some found an excuse, others openly refused; one had the courage to ask him: "Is death so hard?" Then various projects began to agitate his mind; now he was ready to beg for mercy from Galba, his successful opponent; now to ask help from the Parthian refugees, and again to dress himself in mourning, and appear barefooted and unshaven before the public by the rostra, and implore pardon for his crimes; in case that should be refused, to ask permission to exchange the imperial power for the governorship of Egypt. He was ready to carry this project into execution, but his courage failed at the last moment, as he knew that the exasperated people would tear him to pieces before he could reach the Forum. Towards evening he calmed his mind in the hope that there would be time enough to make a decision if he waited until the next day. As midnight approached he awoke, to find that the Prætorians detailed at the gates of the Servilian gardens had retired to their barracks. Servants were sent to rouse the friends sleeping in the villa, but none of them returned. He went around the apartments, finding them closed and deserted. On re-entering his own room he saw that his private attendants had run away, carrying the bed-covers, and the phial of poison. Then he seemed determined to put an end to his life by throwing himself from one of the bridges; but again his courage failed, and he begged to be shown a hiding-place. It was at this supreme moment that Phaon the freedman offered him his suburban villa, situated between the Via Salaria and the Via Nomentana, four miles outside the Porta Collina. The proposal was accepted at once; and barefooted, and dressed in a tunic, with a mantle of the commonest material about his shoulders, he jumped on a horse and started for the gate, accompanied by only four men,—Phaon, Epaphroditus, Sporus, and another whose name is not given.

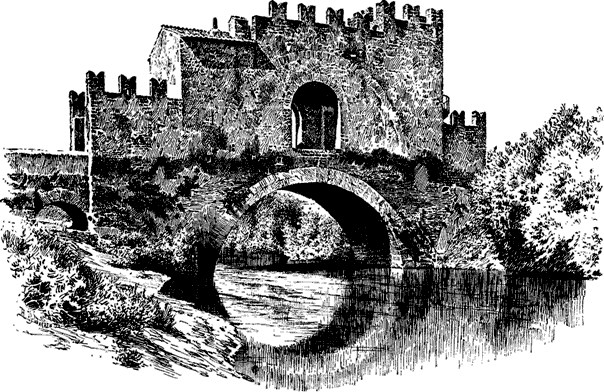

The Ponte Nomentano.

The incidents of the flight were terrible enough to deprive the imperial fugitive of the last spark of hope. The sky was overcast, and heavy black clouds hung close to the earth, the stillness of nature being occasionally broken by claps of thunder. The earth shook just as he was riding past the prætorian camp. He could hear the shouts of the mutinous soldiers cursing his name, while Galba was proclaimed his successor. Farther on, the fugitives met several men hurrying towards the town in search of news. Nero heard some of them telling one another to be sure to run in search of him. Another passer inquired the news from the palace. Before reaching the Ponte Nomentano, Nero's horse, frightened by a corpse which was lying on the roadside, gave a start. The slouched hat and handkerchief, with which the emperor was trying to conceal his face, slipped aside, and just at that moment a messenger from the prætorian camp recognized him, and by force of habit gave the military salute.

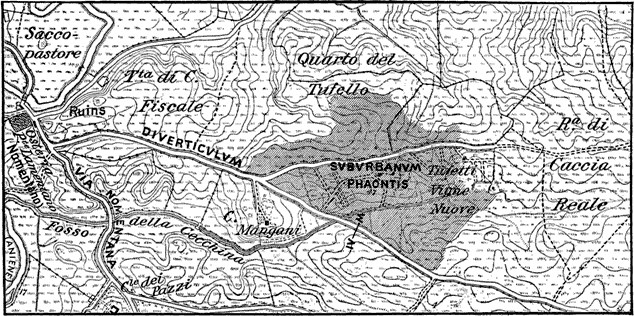

MAP SHOWING THE LOCATION OF PHAON'S VILLA

Beyond the bridge the Via Nomentana divides: the main road, on the right, leads to Nomentum (Mentana); the left to the territory of Ficulea (la Cesarina). It is now called the Strada delle Vigne Nuove. Nero and his followers took this country road. The particulars given by Suetonius suit the present aspect and the nature of the district so exactly that we can follow the four men step by step to the walls of Phaon's villa. The slopes of the hills were then, as they are now, uncultivated, and covered with bushes. There is still a path on the banks of the Fosso della Cecchina, leading to the rear wall of the villa, aversum villæ parietem; and the hillsides are still honeycombed with pozzolana quarries, the angustiæ cavernarum of Suetonius. The villa extends on the tableland, or ridge, between the valleys of la Cecchina and Melaina. Its main gate corresponds exactly with the gate of the Vigna Chiari, the first of the "vigne nuove" on the right as one goes from Rome, at a distance of six kilometres from the threshold of the Porta Collina. For a radius of a thousand feet around the gate, we meet with the typical remains of a Roman villa of the first century,—porticoes, water tanks, and substructions, from the platform of which there is a lovely view over the wooded plains of the Tiber and the Anio, the city, and the hills of the Vatican, and of the Janiculum, which frame the panorama. The site is pleasant, secluded, and quiet, so that it well fulfilled the wish for a secretior latetra expressed by Nero in his hopeless condition. The fugitives dismounted at the turn of the Strada delle Vigne Nuove, and let the horses loose among the brambles. Not wishing to be seen in the open road, they followed the lower path on the banks of the Cecchina, which was concealed by a thick growth of canes. It was necessary to bore a hole in the rear wall of the villa, and while this was being done, Nero quenched his thirst from a pond of stagnant water, near the opening of the pozzolana quarries. Once inside the villa, he was asked to lie down on a couch covered with a peasant's mantle, and was offered a piece of stale bread, and a glass of tepid water. Food he refused, but touched the rim of the cup with his parched lips. It is curious to read in Suetonius of the many grimaces the wretch made before he could determine to kill himself; he made up his mind to do so only when he heard the tramping of the horsemen whom the Senate had sent to arrest him. He then put the dagger into his throat, aided in giving the last thrust by his freedman Epaphroditus. The centurion sent to take him alive arrived before he expired. To him Nero addressed these last words: "Too late! Is this your fidelity?" He gradually sank, his countenance assuming such a frightful expression that all who were present fled in horror. Icelus, freedman of Galba, the newly elected emperor, gave his consent to a decent funeral. Ecloge and Alexandra, his nurses, Acte his mistress, and the three faithful men who had accompanied him in his flight, provided the necessary funds, about five thousand dollars. The body was cremated, wrapped in a sheet of white woven with gold, the same that he had used on his bed New Year's night. The three women collected the ashes and placed them in the tomb of the Domitian family, which stood on the spur of the Pincian Hill which is behind the present church of S. Maria del Popolo. The urn was of porphyry, the altar upon which it stood of Carrara marble, and the tomb itself of Thesian marble. A pathetic discovery has just been made in the Vigna Chiari, on the exact spot of Nero's suicide, by my friend, Cav. Rodolfo Buti, that of the tomb of Claudia Ecloge, the old woman who was so devoted to her nursling. The epitaph is a plain marble slab containing only a name. But this simple inscription, read amid the ruins of Phaon's villa, with every detail of the scene of the suicide before one's eyes, makes more impression on the feelings than would a great monument to her memory. As she could not be buried within or near the family vault of the Domitii on the Pincian, she selected the spot where Nero's remains had been cremated.

"When Nero perished by the justest doomWhich ever the destroyer yet destroy'd,Amidst the roar of liberated Rome,Of nations freed, and the world overjoy'd,Some hands unseen strew'd flowers upon his tomb,—Perhaps the weakness of a heart not voidOf feeling for some kindness done, when powerHad left the wretch an uncorrupted hour."100The original epitaph of Claudia Ecloge has been removed to the Capitoline Museum, where it seems lost among so many other objects of interest; but the student who will select the Vigne Nuove for an afternoon excursion will find there a facsimile, placed by our archæological commission on the front wall of the Casino di Vigna Chiari.

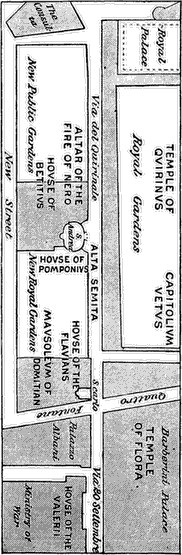

Plan of the Alta Semita.

The Tomb of the Flavian Emperors. The Via del Quirinale-Venti Settembre, which leads from the Quirinal Palace to the Porta Pia, corresponds exactly to the old Alta Semita, which was a street of such importance, on account of its length, straightness, and surroundings, that the whole region (the sixth) was named from it. For our present purpose we shall take into consideration only the first part, between the Quirinal Palace and the Quattro Fontane. It was bordered on the north side by the Temple of Quirinus, discovered and demolished in 1626, and by the Capitolium Vetus, the old Capitol, also destroyed in 1625, by Pope Barberini.

The opposite side of the street was lined with private mansions of families who were eminent in the history of the republic and the empire. The first belonged to Pomponius Atticus, the friend of Cicero, and to his descendants the Pomponii Bassi. Cicero locates it between the Temple of Quirinus and the Temple of Health, that is, near the present church of S. Andrea al Quirinale; and precisely here, in November, 1558, the house was discovered by Messer Uberto Ubaldini, in such perfect condition that the family documents and deeds, inscribed on bronze, were still hanging on the walls of the tablinum,—a fact that is recorded only twice in the annals of Roman excavations.101 The house, seen and described by Manuzio and Ligorio, stood at the corner of the Alta Semita and a side street called "The Pomegranate" (ad malum punicum), and was profusely adorned with statues, colonnades, spacious halls, etc. One of the bronze tablets, which was saved from the ruins, and is now exhibited in the Gallery of the Uffizi, at Florence, states that the municipal council of Ferentinum, assembled in the Temple of Mercury, had placed the city under the guardianship of Pomponius Bassus, a. d. 101. The patronage was accepted by the gallant patrician, and tabulæ hospitales were exchanged between the parties.