полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

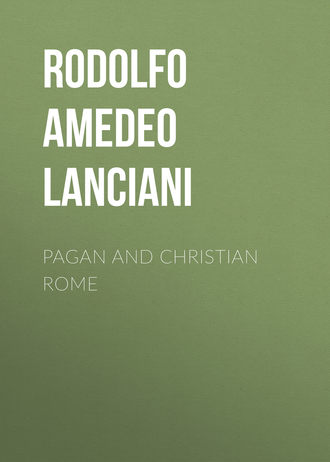

PLAN OF OLD S. PETER'S, SHOWING ITS RELATION TO THE CIRCUS OF NERO

The line of the Via Cornelia, which ran parallel with the north side of the circus, can be traced with precision by the help of the classical, or pagan, tombs discovered at various times along its borders. Let us start from the site of the modern Piazza di S. Pietro. Sante Bartoli, mem. 56-57, says that while Pope Alexander VII. was building the left wing of Bernini's portico, and the fountain of the southern semicircle, a tomb was discovered with a bas-relief above the door representing a marriage-scene ("vi era un bellissimo bassorilievo di un matrimonio antico"). On July 19, 1614, three others were found in the atrium, in one of which was the sarcophagus of Claudia Hermione, the renowned pantomimist. The best discovery, that of pagan tombs exactly on the line with that of S. Peter's, was made in the presence of Grimaldi, November 9, 1616. "On that day," he says, "I entered a square sepulchral room (10 ft. × 11 ft.), the ceiling of which was ornamented with designs in painted stucco. There was a medallion in the centre, with a figure in high relief. The door opened on the Via Cornelia, which was on the same level. This tomb is located under the seventh step in front of the middle door of the church. I am told that the sarcophagus now used as a fountain, in the court of the Swiss Guards, was discovered at the time of Gregory XIII. in the same place, and that it contained the body of a pagan."

We come now to the decisive point, the discoveries made in the time of Urban VIII., when the foundations of his bronze baldacchino were sunk to a great depth, in close proximity to the tomb of S. Peter. The genuineness of the account is proved by the fact that in spite of its great bearing on the question, so little importance was attached to it that, had not Professor Palmieri and Cavaliere Armellini unearthed it from the sacred dust of the Vatican archives, in which it had been buried for three and a half centuries, we should still have been wholly ignorant of its existence.

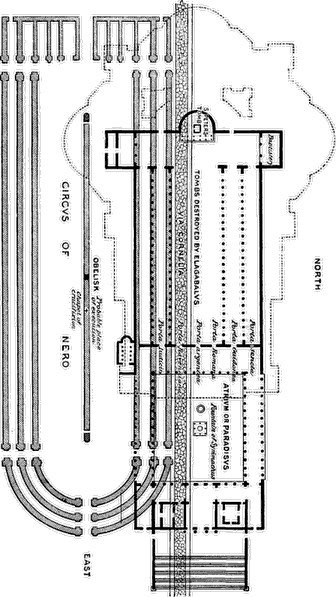

The account published by Armellini72 proves that S. Peter must have been buried in a small plot surrounded by other tombs, and probably protected by an enclosing wall. There were graves which in later ages had been dug in confusion, one above the other, by persons wishing to lie as near as possible to the remains of the apostle; but those of the time of the persecution were arranged in parallel lines,73 and consisted of plain marble coffins bearing no name, and containing one or two bodies, which were dressed like mummies, with bands of darkish linen wound about the body and head. This statement is corroborated by other evidence. In 1615, when Paul V. built the stairs leading to the Confession and the crypts, "several bodies were found lying in coffins, tied with linen bands, as we read of Lazarus in the Gospel: ligatus pedibus et manibus institis. One body only was attired in a sort of pontifical robe. Notwithstanding the absence of written indications we thought they were the graves of the ten bishops of Rome buried in Vaticano." So speaks Giovanni Severano on page 20 of his book "Memorie sacre delle sette chiese di Roma," which was printed in 1629. Francesco Maria Torrigio, who witnessed the exhumations with cardinal Evangelista Pallotta, adds that the linen bands were from two to three inches wide, and that they must have been soaked in aromatics. One of the coffins bore, however, the name LINVS.74 Let us now refer to the "Liber Pontificalis," the authority of which as an historical text-book cannot be doubted, since the critical publication of Louis Duchesne.75 After describing the "deposition of S. Peter in the Vatican, near the circus of Nero, between the Via Aurelia and the Via Triumphalis, iuxta locum ubi crucifixus est (near the place of his crucifixion)," it proceeds to say that Linus "was buried side by side with the remains of the blessed Peter, in the Vatican, October 24." Even if we were disposed to doubt Torrigio's correctness in copying the name of the second bishop of Rome,76 the fact of his burial in this place seems to be certain, because Hrabanus Maurus, a poet of the ninth century, speaks of Linus's tomb as visible and accessible, in the year 822. Another man was present at the discoveries enumerated by Torrigio and Severano; the master-mason Benedetto Drei, whose drawing, printed in 1635, has become very rare.

The reader will remark how perfectly Drei's sketch fits the written accounts of the other eye-witnesses, even in the detail of the child's grave—"sepoltura di un bambino,"—which is distinctly mentioned by them.

The privileges which the Roman law allowed to sepulchres, even of criminals, made it possible for the Christians to keep these graves in good order, with impunity. However, they ran a great risk under Elagabalus. Among the many extravagances in which this youth indulged in connection with the circus, such as driving a chariot drawn by four camels, or letting loose thousands of poisonous snakes among the spectators, Lampridius mentions a race of four quadrigæ drawn by elephants, which was to be run in the Vatican; and as the track inside the circus was obviously too narrow for such an attempt, another was prepared outside by removing or destroying those tombs of the Via Cornelia which stood in the way.77 It is more than probable that the body of S. Peter was at that time transferred to a temporary place of shelter at the third milestone of the Via Appia, which I shall have opportunity to describe in the seventh chapter.78

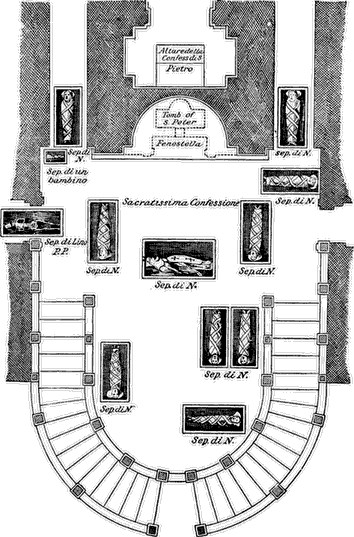

After the defeat of Maxentius in the plains of Torre di Quinto, Constantine "raised a basilica over the tomb of the blessed Peter, which he enclosed in a bronze case. The altar above was decorated with spiral columns carved with vines which he had brought over from Greece."79

The basilica was erected hurriedly at the expense of the adjoining circus. Constantine took advantage of its three northern walls, which supported the seats of the spectators on the side of the Via Cornelia, to rest upon them the left wing of the church, and built new foundations for the right wing only. His architect seems to have been rather negligent in his measurements, because the tomb of S. Peter did not correspond exactly with the axis of the nave, and was not in the centre of the apse, being some inches to the left.

The columns were collected from everywhere. I have discovered in one of the note-books of Antonio da Sangallo the younger a memorandum of the quality, quantity, size, color, etc., of one hundred and thirty-six shafts. Nearly all the ancient quarries are represented in the collection, not to speak of styles and ages. An exception must be made in favor of the twelve columns of the Confession, mentioned above, which, according to the "Liber Pontificalis," were brought over from Greece (columnæ vitineæ quas de Græcia perduxit: i. 176). I doubt the correctness of the statement; they appear to me a fantastic Roman work of the third century.

PLAN OF THE GRAVES SURROUNDING THAT OF S. PETER DISCOVERED AT THE TIME OF PAUL V.

(From a rare engraving by Benedetto Drei, head master mason to the Pope. The site of the tomb of S. Peter and the Fenestella are indicated by the author)

The Colonna Santa.

At all events the surmise of the "Liber Pontificalis" shows how little credit is to be attached to the tradition that they once belonged to the Temple of Solomon at Jerusalem.80 There are eleven left: of which eight ornament the balconies under the dome; two, the altar of S. Mauritius, and one (reproduced in our illustration) the Cappella della Pietà, the first on the right. It is called the colonna santa (the holy column), because it was formerly used for the exorcism of evil spirits. It was enclosed in a marble pluteus by Cardinal Orsini, in 1438.

The walls of the church were patched with fragments of tiles (tegolozza) and stone, except the apse and the arches, which were built of good bricks bearing the name of the emperor:—

Dominus Noster CONSTANTINVS AVGustusGrimaldi says that he could not find two capitals or two bases alike. He says also that the architraves and friezes differed from one intercolumniation to another, and that some of them were inscribed with the names and praises of Titus, Trajan, Gallienus, and others. On each side of the first gateway, at the foot of the steps, were two granite columns, with composite capitals, representing the bust of the emperor Hadrian framed in acanthus leaves.

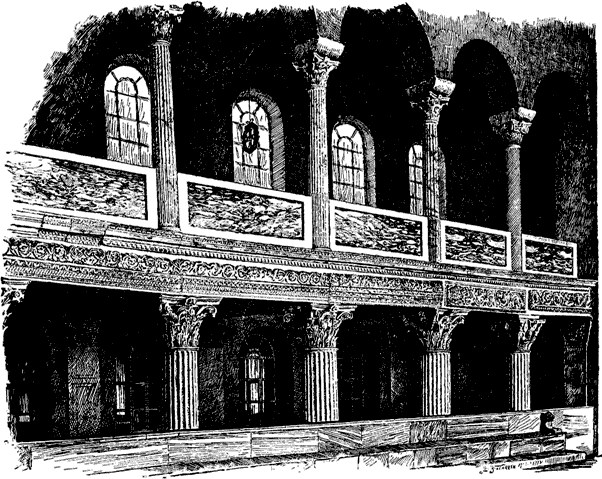

The accompanying illustration, which was copied from an engraving of Ciampini, shows the aspect of the interior in the year 1588.

It gives a fairly good idea of the decorations of the nave, in their general outline; but fails to show the details of Constantine's patchwork. His system of structure may be better understood by referring to another of his creations, the basilica of S. Lorenzo fuori le Mura, of which a section of the interior is illustrated on p. 135.

The atrium or quadri-portico was entered by three gateways, the middle one of which had doors of bronze inlaid with silver. The nielli represented castles, cities, and territories which were subject to the apostolic see. The doors were stolen in 1167, and carried to Viterbo as trophies of war.

View of a section of the Nave of old S. Peter's (South Side).

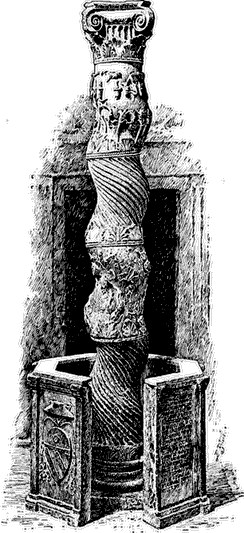

The fountain in the centre of the atrium was a masterpiece of the time of Symmachus (498-514), who had a great predilection for buildings connected with hygiene and cleanliness, such as baths, fountains, and necessaria.81 The fountain is described in my "Ancient Rome," p. 286; let me add here the particulars concerning its destruction.

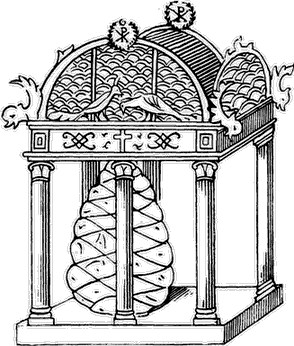

Nave of San Lorenzo fuori le Mura.

The structure was composed of a square tabernacle supported by eight columns of red porphyry, with a dome of gilt bronze. Peacocks, dolphins, and flowers, also of gilt bronze, were placed on the four architraves, from which jets of water flowed into the basin below. The border of the basin was made of ancient marble bas-reliefs, representing panoplies, griffins, etc. On the top of the structure were semicircular bronze ornaments worked "à jour," that is, in open relief, without background, and crowned by the monogram of Christ. This gem of the art of the sixth century was ruthlessly destroyed by Paul V. The eight columns of porphyry, one of which was ornamented with an imperial bust in high relief, have disappeared, and so have the bas-reliefs of the border of the fountain, although Grimaldi claims to have saved one. The bronzes were removed to the garden of the Vatican, but, with the exception of the pine-cone and two peacocks, they were doomed to share the fate of the marbles. In 1613 the semicircular pediments, the four dolphins, two of the peacocks, and the dome were melted to provide the ten thousand pounds of metal required for the casting of the statue of the Madonna which was placed by Paul V. on the column of S. Maria Maggiore.

The Fountain of Symmachus.

The most important monument of the atrium, after the fountain, was the tomb of the emperor Otho II. († 983), or what was believed to be his tomb, as some contemporary writers attribute it to Cencio, prefect of Rome, who died 1077. The body lay in a marble sarcophagus, which was screened by slabs of serpentine, the whole being surmounted by a porphyry cover supposed to have come from Hadrian's mausoleum. The mosaic picture above represented the Saviour between SS. Peter and Paul. This historical monument was demolished by Carlo Maderno in the night of October 20, 1610. The coffin was removed to the Quirinal and turned into a water-trough. Grimaldi saw it last, near the entrance gate from the side of the Via dei Maroniti. The panels of serpentine were used in the new building, the picture of the Saviour was removed to the Grotte; the cover of porphyry was turned upside down, and made into a baptismal font.

The church was entered by five doors, named respectively (from left to right) the Porta Iudicii, Ravenniana, argentea or regia maior, Romana, and Guidonea. The first was called the "Judgment Door," because funerals entered or passed out through it. The name "Ravenniana" seems to have originated in the barracks of marine infantry of the fleet of Ravenna, detailed for duty in Rome, or else from the name "Civitas Ravenniana" given to the Trastevere in the epoch of the decadence. It was reserved for the use of men, as the fourth or Romana was for women, and the fifth, Guidonea, for tourists and pilgrims. The main entrance, called the "Royal," or "Silver Door," was opened only on grand occasions. Its name was derived from the silver ornaments affixed to the bronze by Honorius I. (a. d. 626-636) in commemoration of the reunion of the church of Histria with the See of Rome. According to the "Liber Pontificalis" nine hundred and seventy-five pounds of silver were used in the work. There were the figures of S. Peter on the left and S. Paul on the right, surrounded by halos of precious stones. They were the prey of the Saracens in 845. Leo IV. restored them to a certain extent, changing the subject of the silver nielli. In the year 1437, Antonio di Michele da Viterbo, a Dominican lay brother, was commissioned by Pope Eugenius IV. to carve new side doors in wood, while Antonio Filarete and Simone Bardi were asked to model and cast, in bronze, those of the middle entrance.

On entering the nave the visitor was struck by the simplicity of Constantine's design, and by the multitude and variety of later additions, by which the number of altars alone had been increased from one to sixty-eight. Ninety-two columns supported an open roof, the trusses of which were of the kingpost pattern. In spite of frequent repairs, resulting from fires, decay, and age, some of these trusses still bore the mark of Constantine's name. They were splendid specimens of timber. Filippo Bonanni, whose description of S. Peter's deserves more credit than all the rest together, except Grimaldi's manuscripts,82 says that on February 21, 1606, he examined and measured the horizontal beam of the first truss from the façade, which Carlo Maderno had just lowered to the floor; it was seventy-seven feet long and three feet thick. The same writer copies from a manuscript diary of Rutilio Alberini, dated 1339, the following story relating to the same roof: "Pope Benedict XII. (1334-1342) has spent eighty thousand gold florins in repairing the roof of S. Peter's, his head carpenter being maestro Ballo da Colonna. A brave man he was, capable of lowering and lifting those tremendous beams as if they were motes, and standing on them while in motion. I have seen one marked with the name of the builder of the church (CONstantine); it was so huge that all kinds of animals had bored their holes and nests in it. The holes looked like small caverns, many yards long, and gave shelter to thousands of rats." Grimaldi climbed the roof at the beginning of 1606, and describes it as made of three kinds of tiles,—bronze, brick, and lead. The tiles of gilt bronze were cast in the time of the emperor Hadrian for the roof of the Temple of Venus and Rome. Pope Honorius I. (625-640) was allowed by Heraclius to make use of them for S. Peter's. The brick tiles were all stamped with the seal of King Theodoric, or with the motto BONO ROMÆ (for the good of Rome). The lead sheets bore the names of various Popes, from Innocent III. (1130-1138) to Benedict XII. All these precious materials for the chronology and history of the basilica have disappeared, save a few planks from the roof, with which the doors of the modern church were made.

Another sight must have struck the pilgrim as he first crossed the threshold, that of the "triumphal arch" between the nave and the transept, glistening with golden mosaics. We owe to Prof. A. L. Frothingham, Jr., of Baltimore, the knowledge of this work of art, he having found the description of it by cardinal Jacobacci in his book "De Concilio" (1538). The mosaics represented the emperor Constantine being presented by S. Peter to the Saviour, to whom he was offering a model of the basilica. It was destroyed, with the dedicatory inscription, in 1525.83

The baptistery erected by Pope Damasus after the discovery of the springs of the Aqua Damasiana, and restored by Leo III. (795-816), stood at the end of the north transept.84 One of its inscriptions contained the verse—

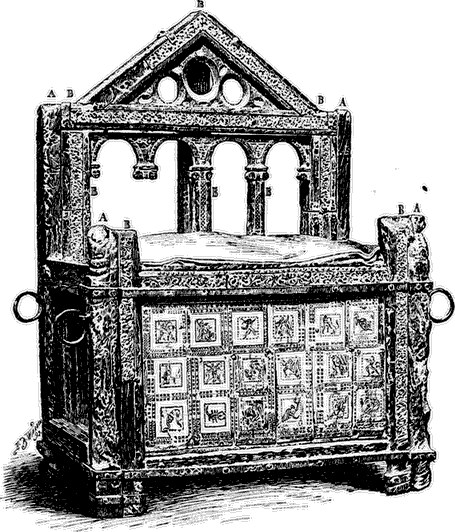

"Una Petri sedes unum verumque lavacrum,"—an allusion both to the baptismal font and to the "chair of S. Peter's," upon which the Popes sat after baptizing the neophytes. The cathedra is mentioned by Optatus Milevitanus, Ennodius of Pavia, and by more recent authors, as having changed place many times, until Alexander VII., with the help of Bernini and Paul Schor, placed it in a case of gilt bronze at the end of the apse. It has been minutely examined and described several times by Torrigio, Febeo, and de Rossi. I saw it in 1867. The framework and a few panels of the relic may possibly date from apostolic times; but it was evidently largely restored after the peace of the Church. The upright supports at the four corners were whittled away by early pilgrims.

The Chair of S. Peter; after photograph from original. – A Oak wood, much decayed, and whittled by pilgrims. B Acacia wood, inlaid with ivory carvings.

Another work of art deserves attention, because its origin, age, and style are still matters of controversy. I mean the bronze statue of S. Peter (see p. 142) placed against the right wall of the nave, near the S. Andrew of Francis de Quesnoy. Without attempting a discussion which would be inconsistent with the spirit of this book, I can safely state that the theories suggested by modern Petrographists, from Torrigio to Bartolini, deserve no credit. The statue is not the Capitoline Jupiter transformed into an apostle; nor was it cast with the bronze of that figure; it never held the thunderbolt in the place of the keys of heaven. The statue was cast as a portrait of S. Peter; the head belongs to the body; the keys and the uplifted fingers of the right hand are essential and genuine details of the original composition. The difficulty, and it is a great one, consists in stating its age. There is no doubt that Christian sculptors modelled excellent portrait-statues in the second and third centuries: as is proved by that of Hippolytus (see p. 143), discovered in 1551 in the Via Tiburtina, and now in the Lateran Museum, a work of the time of Alexander Severus.

There is no doubt also that there is a great similarity between the two, in the attitude and inclination of the body, the position of the feet, the style of dress, and even the lines of the folds. But portrait-statues of bronze may belong to any age; because, while the sculptor in marble is obliged to produce a work of his own hands and conception, and the date of a marble statue can therefore be determined by comparison with other well-known works, the caster in bronze can easily reproduce specimens of earlier and better times by taking a mould from a good original, altering the features slightly, and then casting it in excellent bronze. This seems to be the case with this celebrated image. I know that the current opinion makes it contemporary with the erection of Constantine's basilica; but to this I cannot subscribe on account of the comparatively modern shape of the keys. One of two things must be true,—either that these keys are a comparatively recent addition, in which case the statue may be a work of the fourth century, or they were cast together with the figure. If the latter be the fact the statue is of a comparatively recent age. Doubts on the subject might be dispelled by a careful examination of these crucial details, which I have not been able to undertake to my satisfaction.

Bronze Statue of S. Peter.

The destruction of old S. Peter's is one of the saddest events in the history of the ruin of Rome. It was done at two periods and in two sections, a cross wall being raised in the mean time in the middle of the church to allow divine service to proceed without interruption, while the destruction and the rebuilding of each half was accomplished in successive stages.

Statue of S. Hippolytus.

The work began April 18, 1506, under Julius II. It took exactly one century to finish the western section, from the partition wall to the apse. The demolition of the eastern section began February 21, 1606. Nine years later, on Palm Sunday, April 12, 1615, the jubilant multitudes witnessed the disappearance of the partition wall, and beheld for the first time the new temple in all its glory.

It seems that Paul V., Borghese, to whom the completion of the great work is due, could not help feeling a pang of remorse in wiping out forever the remains of the Constantinian basilica. He wanted the sacred college to share the responsibility for the deed, and summoned a consistory for September 26, 1605, to lay the case before the cardinals. The report revealed a remarkable state of things. It seems that while the foundations of the right side of the church built by Constantine had firmly withstood the weight and strain imposed upon them, the foundation of the left side, that is, the three walls of the circus of Caligula, which had been built for a different purpose, had yielded to the pressure so that the whole church, with its four rows of columns, was bending sideways from right to left, to the extent of three feet seven inches. The report stated that this inclination could be noticed from the fact that the frescoes of the left wall were covered with a thick layer of dust; it also stated that the ends of the great beams supporting the roof were all rotten and no longer capable of bearing their burden. Then cardinal Cosentino, the dean of the chapter, rose to say that, only a few days before, while mass was being said at the altar of S. Maria della Colonna, a heavy stone had fallen from the window above, and scattered the congregation. The vote of the sacred college was a foregone conclusion. The sentence of death was passed upon the last remains of old S. Peter's; a committee of eight cardinals was appointed to preside over the new building, and nine architects were invited to compete for the design. These were Giovanni and Domenico Fontana, Flaminio Ponzio, Carlo Maderno, Geronimo Rainaldi, Nicola Braconi da Como, Ottavio Turiano, Giovanni Antonio Dosio, and Ludovico Cigoli. The competition was won by Carlo Maderno, much to the regret of the Pope, who was manifestly in favor of his own architect, Flaminio Ponzio. The execution of the work was marked by an extraordinary accident. On Friday, August 27, 1610, a cloud-burst swept the city with such violence that the volume of water which accumulated on the terrace above the basilica, finding no outlet but the winding staircases which pierced the thickness of the walls, rushed down into the nave in roaring torrents and inundated it to a depth of several inches. The Confession and tomb of the apostle were saved only by the strength of the bronze door.

It is very interesting to follow the progress of the work in Grimaldi's diary, to witness with him the opening and destruction of every tomb worthy of note, and to make the inventory of its contents. The monuments were mostly pagan sarcophagi, or bath basins, cut in precious marbles; the bodies of Popes were wrapped in rich robes, and wore the "ring of the fisherman" on the forefinger. Innocent VIII., Giovanni Battista Cibo (1484-1492), was folded in an embroidered Persian cloth; Marcellus II., Cervini (1555), wore a golden mitre; Hadrian IV., Breakspeare (1154-1159), is described as an undersized man, wearing slippers of Turkish make, and a ring with a large emerald. Callixtus III. and Alexander VI., both of the Borgia family, have been twice disturbed in their common grave: the first time by Sixtus V., when he removed the obelisk from the spina of the circus to the piazza; the second by Paul V. on Saturday, January 30, 1610, when their bodies were removed to the Spanish church of Montserrat, with the help of the marquis of Billena, ambassador of Philip III., and of cardinal Çapata.