полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

The connection of the house with the apostolate of SS. Peter and Paul made it very popular from the beginning. Laymen and clergymen alike contributed to transform it into a handsome church. Pope Siricius (384-397), his acolytes Leopardus, Maximus and Ilicius, and Valerius Messalla, prefect of the city (396-403), ornamented it with mosaics, colonnades, and marble screens, and built on the west side of the Vicus Patricius a portico more than a thousand feet long, which led from the Subura to the vestibule of the church.

In 1588 Cardinal Enrico Caetani disfigured the building with unfortunate restorations. He laid his hands even on the mosaics of the apse, considered by Poussin the best in Rome, as they are the oldest (a. d. 398), and mutilated the figures of two apostles, a portion of the foreground and the historical inscription. His architect, Francesco Ricciarelli da Volterra, while excavating the foundations for one of the pilasters of the new dome, made a discovery, which is described by Gaspare Celio64 in the following words:—

"While Francesco Volterra was restoring the church of S. Pudentiana, and building the foundations of the dome, the masons discovered a marble group of the Laocoön, broken into many pieces. Whether from ill will or from laziness, they left the beautiful work of art at the bottom of the trench, and brought to the surface only a leg, without the foot, and a wrist. It was given to me, and I used to show it with pride to my artist friends, until some one stole it. It was a replica of the Belvedere group, considerably larger, and so beautiful that many believe it to be the original described by Pliny (xxvi. 5). The ancients, like the moderns, were fond of reproducing masterpieces. If the replica of the Pietà of Michelangelo, which we admire in the church of S. Maria dell' Anima, had been found under the ground, would we not consider it a better work than the original in S. Peter's? Francesco Volterra complained to me many times about the slovenliness of the masons; he says that, working by contract (a cottimo), they were afraid they should get no reward for the trouble of bringing the group to the surface."

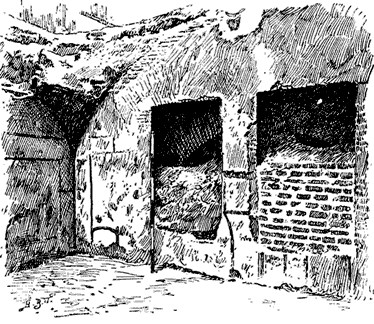

Remains of the House of Pudens, discovered in 1870.

Remains of the house of Pudens were found in 1870. They occupy a considerable area under the neighboring houses.65

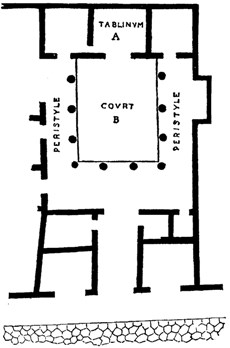

Plan of Pompeian House.

The theory accepted by some modern writers as regards the transformation of these halls of prayer into regular churches is this. The prayer-meetings were held in the tablinum (A) or reception room of the house, which, as shown in the accompanying plan, opened on the atrium or court (B), and this was surrounded by a portico or peristyle (C). In the early days of the gospel the tablinum could easily accommodate the small congregation of converts; but, as this increased in numbers and the space became inadequate, the faithful were compelled to occupy that section of the portico which was in front of the meeting hall. When the congregation became still larger, there was no other way of accommodating it, and sheltering it from rain or sun, than by covering the court either with an awning or a roof. There is very little difference between this arrangement and the plan of a Christian basilica. The tablinum becomes an apse; the court, roofed over, becomes the nave; the side wings of the peristyle become the aisles.

Among the Roman churches whose origin can be traced to the hall of meeting, besides those of Pudens and Prisca already mentioned, the best preserved seems to be that built by Demetrias at the third milestone of the Via Latina, near the "painted tombs." Demetrias, daughter of Anicius Hermogenianus, prefect of the city, 368-370, and of Tyrrania Juliana, a friend of Augustine and Jerome, enlarged the oratory already existing in the tablinum of the Anician villa, and transformed it into a beautiful church, afterwards dedicated to S. Lorenzo. Church and villa were discovered in 1857, and, together with the painted tombs of the Via Latina, are now the property of the nation. The stranger could not find a pleasanter afternoon drive. The church is well preserved, and still contains the metric inscription in praise of Demetrias which was composed by Leo III. (795-816).66

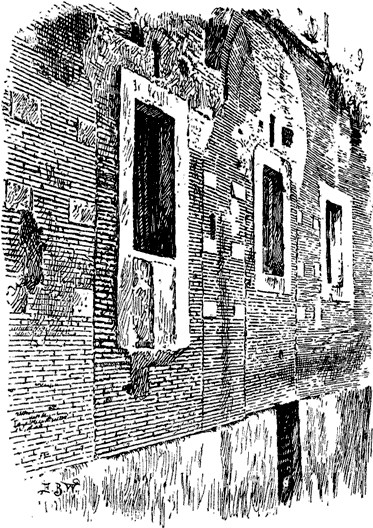

Remains of the House of Pudens. Front Waal, pierced by modern windows.

II. Scholæ. The laws of Rome were very strict in regard to associations, which, formed on the pretence of amusement, charity, or athletic sports, were apt to degenerate into political sects. Exception was made in favor of the collegia funeraticia, which were societies formed to provide a decent funeral and place of burial for their members. An inscription discovered at Civita Lavinia quotes the very words of a decree of the Senate on this subject: "It is permitted to those who desire to make a monthly contribution for funeral expenses to form an association." "These clubs or colleges collected their subscriptions in a treasure-chest, and out of it provided for the obsequies of deceased members. Funeral ceremonies did not cease when the body or the ashes was laid in the sepulchre. It was the custom to celebrate on the occasion a feast, and to repeat that feast year by year on the birthday of the dead, and on other stated days. For the holding of these feasts, as well as for other meetings, special buildings were erected, named scholæ; and when the societies received gifts from rich members or patrons, the benefaction frequently took the shape of a new lodge-room, or of a ground for a new cemetery, with a building for meetings."67 The Christians took advantage of the freedom accorded to funeral colleges, and associated themselves for the same purpose, following as closely as possible their rules concerning contributions, the erection of lodges, the meetings, and the αγαπαι or love feasts; and it was largely through the adoption of these well-understood and respected customs that they were enabled to hold their meetings and keep together as a corporate body through the stormy times of the second and third centuries.

Two excellent specimens of scholæ connected with Christian cemeteries and with meetings of the faithful have come down to us, one above the Catacombs of Callixtus, the other above those of Soter.

The first edifice has the shape of a square hall with three apses,—cella trichora. It is built over the part of the catacombs which was excavated at the time of Pope Fabianus (a. d. 236-250), who is known to have raised multas fabricas per cæmeteria; it is probably his work, as the style of masonry is exactly that of the first half of the third century. The original schola was covered by a wooden roof, and had no façade or door. In the year 258, while Sixtus II., attended by his deacons Felicissimus and Agapetus, was presiding over a meeting at this place in spite of the prohibition of Valerian, a body of men invaded the schola, murdered the bishop and his acolytes, and razed the building nearly to the level of the ground. Half a century later, in the time of Constantine, it was restored to its original shape, with the addition of a vaulted roof and a façade. The line which separates the old foundations of Fabianus from the restorations of the age of peace is clearly visible. Later the schola was changed into a church and dedicated to the memory of Syxtus, who had lost his wife there, and of Cæcilia, who was buried in the crypt below. It became a great place of pilgrimage, and the itineraries mention it as one of the leading stations on the Appian Way.

When de Rossi first visited the place, fifty years ago, this famous schola or church of Syxtus and Cæcilia was used as a wine-cellar, while the crypts of Cæcilia and Cornelius were used as vaults. Thanks to his initiative the monument has again become the property of the Church of Rome; and after a lapse of ten or twelve centuries divine service was resumed in it on the twentieth day of April of the present year. Its walls have been covered with inscriptions found in the adjoining cemetery.

The theory suggested by modern writers with regard to the scholæ is very much the same as that concerning the tablinum of private houses. At first the small building was sufficient to meet the wants of a small congregation; with the increase of the members it became a presbiterium, or place reserved for the bishop or the clergy, while the audience stood outside, under the shelter of a tent, or a roof supported by upright beams. Here also we have all the architectural elements of the Christian basilica.

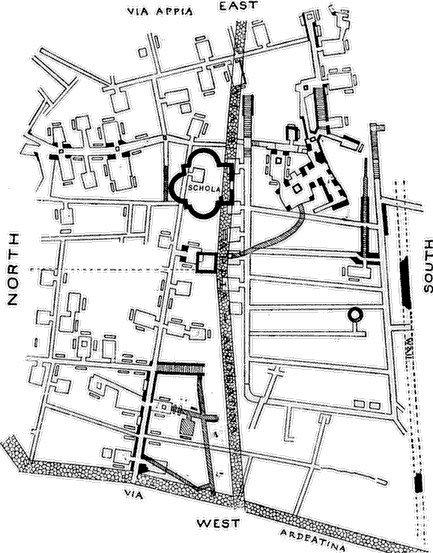

PLAN OF SCHOLA ABOVE THE CATACOMBS OF CALLIXTUS

(From Nortet's Les Catacombes Romaines)

The name schola, in its original meaning, has never died out in Rome; and as in the Middle Ages we had the scholæ of the Saxons, the Greeks, the Frisians, and the Lombards, so we have in the present day those of the Jews (gli scoli degli ebrei).

III. Oratories and churches built over the tombs of martyrs and confessors. The sacred buildings of this class are, or were formerly, outside the walls, as burial was not allowed within city limits. To explain their origin and to understand their significance we must bear in mind the following rules. The action of the Roman law towards the Christians, that is, towards persons accused of atheism and rebellion against the Empire, resulted in the execution of those who were convicted. Except in extraordinary cases, the body of the victim could be claimed by relatives and friends and buried with due honors. In chapters vi. and vii. instances will be quoted of the erection of imposing tombs to the memory of Roman patricians, generals and magistrates, who were put to death under the imperial régime. The same privileges of burial were granted to the Christians, who preferred, however, the modesty and safety of a grave in the heart of the catacombs to the pompous luxury of a mausoleum above ground. The grave of a martyr was an object of consideration, and was often visited by pilgrims, who adorned it with wreaths and lights on the anniversary of his execution. After the end of the persecutions the first thought of the victorious church was to honor the memory of those who had fought so gallantly for the common cause, and who at the sacrifice of their lives had hastened the advent of the days of freedom and peace. No better altar than those graves could be chosen for the celebration of divine service; but they were sunk deep in the ground, and the cubicula of the catacombs were hardly capable of containing the officiating clergy, much less the multitudes of the faithful. Touching the graves, removing them to a more suitable place, was out of the question; in the eyes of the early Christians no more impious sacrilege could be perpetrated. There was but one way left to deal with the difficulty; that of cutting away the rock over and around the grave, and thereby gaining such space as was deemed sufficient for the erection of a basilica. The excavation was done in conformity with two rules,—that the tomb of the martyr should occupy the place of honor in the middle of the apse, and that the body of the church should be to the east of the tomb, except in cases of "force majeure," as when a river, a public road, or some other such obstacle made it necessary to vary this principle.

Such is the origin of the greatest sanctuaries of Christian Rome. The churches of S. Peter on the Via Cornelia, S. Paul on the Via Ostiensis, S. Sebastian on the Via Appia, S. Petronilla on the Via Ardeatina, S. Valentine on the Via Flaminia, S. Hermes on the Via Salaria, S. Agnes on the Via Nomentana, S. Lorenzo on the Via Tiburtina, and fifty other historical structures, owe their existence to the humble grave which no human hand was allowed to transfer to a more suitable and healthy place.

When these graves were not very deep, the floor of the basilica was almost level with the ground, as in the case of S. Peter's, S. Paul's, and S. Valentine's; in other cases it was sunk so deep in the heart of the hill that only the roof and the upper tier of windows were seen above the ground, as in the basilicas of S. Lorenzo, S. Petronilla, etc. There are two or three basilicas built, or rather excavated, entirely under ground. The best specimen is that of S. Hermes on the old Via Salaria.

It soon became evident that edifices sunk in such awkward places could hardly answer their purpose, on account of dampness and the want of air and light. Several steps were taken to remedy the evil. Large portions of the hills were cut away so as to make the edifice free on one or two sides at least, and outlets for rain or spring water provided. We have a description of the system of drainage of S. Peter's, written by its originator, Pope Damasus, in a poem the original of which, discovered by Pope Paul V., in 1607, is preserved in the Grotte Vaticane:—

"The hill was abundant in springs; and the water found its way to the very graves of the saints. Pope Damasus determined to check the evil. He caused a large portion of the Vatican Hill to be cut away; and by excavating channels and boring cuniculi he drained the springs so as to make the basilica dry and also to provide it with a steady fountain of excellent water."68

The Acqua Damasiana is still in use, and has the honor of supplying the apartments of the Pope. Its feeding-springs are located at S. Antonino, twelve hundred yards west of S. Peter's. The aqueduct of Damasus, restored in 1649 by Innocent X., is neatly built in the old Roman style; the channel is four feet nine inches high, three feet three inches wide, and runs through the clay of the hill at a depth of ninety-eight feet. The principal fountain, in the Cortile di S. Damaso, was designed by Algardi in 1649.

Apparently the works accomplished for the same purpose at S. Lorenzo fuori le Mura, by Pope Pelagius II. (579-590), were no less important. They are described in another poem, a modern copy of which (1860) is to be seen on the side of the mosaic in the apsidal arch. The poem relates how the hill of Cyriaca was cut away, and how, in consequence of the excavation, the church became light, accessible, and free from the danger of landslips and inundations. The importance of the work of Pelagius is rather exaggerated by the composer of the poem. The church was never free from dampness and want of air and light until the pontificate of Pius IX., who cut away another section of the hill.

The damage done to the catacombs by the builders of these sunken basilicas is incalculable. Thousands of graves must have been sacrificed for the embellishment of one.

The reader cannot expect to find in these pages a description of this class of basilicas; that of S. Peter's alone would require several volumes. I have in my modest library not less than twenty-two volumes on the subject, an insignificant fraction of the Petrine literature. And what do we know about S. Peter's? Very little in comparison with the amount of knowledge that lies yet unpublished in the volumes of Grimaldi,69 in the archives of the Vatican, in epigraphic, historical and diplomatic documents scattered among various European libraries.

The history of the building has yet to be written. Duchesne's "Liber Pontificalis" and de Rossi's second volume of the "Inscriptiones Christianæ" provide the necessary foundations for such a work. Let us hope that the Vatican will soon find its own Rohault de Fleury.70

The following sketch of the origin of the two leading sacred edifices of Rome may answer the scope of the present chapter. But let me repeat once again the declaration that I write about the monuments of ancient Rome from a strictly archæological point of view, avoiding questions which pertain, or are supposed to pertain, to religious controversy. For the archæologist the presence and execution of SS. Peter and Paul in Rome are facts established beyond a shadow of doubt by purely monumental evidence. There was a time when persons belonging to different creeds made it almost a case of conscience to affirm or deny a priori those facts, according to their acceptance or rejection of the tradition of any particular church. This state of feeling is a matter of the past, at least for those who have followed the progress of recent discoveries and of critical literature. However, if my readers think that I am assuming as proved what they still consider subject for discussion, I beg to refer them to some of the standard works published on this subject by writers who are above the suspicion of partiality. Such are Döllinger's "First Age of Christianity" (translated by Henry Nutcombe Oxenham, second edition, London, Allen, 1867); Bishop Lightfoot's "Apostolic Fathers," part ii., London, Macmillan, 1885, one of the most beautiful and conclusive works on early Christian history and literature; and de Rossi's "Bullettino di archeologia cristiana," for 1877. Bishop Lightfoot justly remarks that when Ignatius—the second apostolic father, a contemporary of Trajan—writes to the Romans "I do not command you, like Peter and Paul," the words are full of meaning, if we suppose him to be alluding to the personal relations of the two apostles with the Roman Church. In fact, the reason for his use of this language is the recognition of the visit to Rome of S. Peter as well as S. Paul, which is persistently maintained in early tradition; and thus it is a parallel to the joint mention of the two apostles in "Clement of Rome" (p. 357). Döllinger adds: "That S. Peter worked in Rome is a fact so abundantly proved and so deeply imbedded in the earliest Christian history, that whoever treats it as a legend ought in consistency to treat the whole of the earliest church history as legendary, or at least, quite uncertain. His presence in Corinth is obviously connected with his journey to Rome, and no one will accept the one and deny the other (see Cor. i. 12; iii. 22; xi. 22, 23; Clement's Ep. 47, etc.) Clement again reminds the Corinthians of the 'martyrdom of Peter and Paul … among us,' meaning Rome. The very mention implies that S. Peter's martyrdom was a well-known fact, and it is inconceivable that his execution should have been known and not the place where it occurred, or that the place could have been forgotten, and a wrong one substituted some years later. And when Ignatius writes to the Romans—'I do not command you like Peter and Paul; they were apostles'—it is clear, without any explanation, that he desires to remind them of the two men who, as founders and teachers, had been the glory of the Church."

The Ebionite document, called "The Preaching of Peter," produced about the time of Ignatius, or very soon after, and used by Heracleon in Hadrian's time, is manifestly founded on the undisputed fact of S. Peter having labored at Rome. It is inconceivable that the author of the Ebionite document should have put forward a groundless fable, about the theatre of S. Peter's operations, at a time when many who had seen him must have been still alive. Eusebius, who had the writings of Papias (and Hegesippos) before him, maintains with Clement, that S. Peter wrote his Epistle at Rome (Euseb. ii. 15). Papias, a disciple of S. John, speaking of this epistle declares that "Babylon" means expressly the capital of the empire. Hegesippos, a Christian Jew of Palestine, who came to Rome in the first half of the second century, makes Linus the first bishop after the apostles, in accordance with Irenæus, who says: "After Peter and Paul had founded the Roman church and set it in order, they gave over the episcopate to Linus." If we consider that Hegesippos came to Rome to investigate, among other things, the succession of local bishops for the short period of eighty-three years, that he certainly spoke with persons whose fathers could remember the presence of the apostles, we cannot help accepting his evidence as conclusive.

The main objection brought forward by the opponents is that, after the incident at Antioch, we have no positive knowledge of the actions and travels of S. Peter. Still, there is nothing to contradict the assumption of his journey to Rome, and his confession and execution there. The fact was so generally known that nobody took the trouble to write a precise statement of it, because nobody dreamed that it could be denied. How is it possible to imagine that the primitive Church did not know the place of the death of its two leading apostles? In default of written testimony let us consult monumental evidence.

There is no event of the imperial age and of imperial Rome which is attested by so many noble structures, all of which point to the same conclusion,—the presence and execution of the apostles in the capital of the empire. When Constantine raised the monumental basilicas over their tombs on the Via Cornelia and the Via Ostiensis; when Eudoxia built the church ad Vincula; when Damasus put a memorial tablet in the Platonia ad Catacumbas; when the houses of Pudens and Aquila and Prisca were turned into oratories; when the name of Nymphæ Sancti Petri was given to the springs in the catacombs of the Via Nomentana; when the twenty-ninth day of June was accepted as the anniversary of S. Peter's execution; when Christians and pagans alike named their children Peter and Paul; when sculptors, painters, medallists, goldsmiths, workers in glass and enamel, and engravers of precious stones, all began to reproduce in Rome the likenesses of the apostles, at the beginning of the second century, and continued to do so till the fall of the empire; must we consider them all as laboring under a delusion, or as conspiring in the commission of a gigantic fraud? Why were such proceedings accepted without protest from whatever city, from whatever community, if there were any other which claimed to own the genuine tombs of SS. Peter and Paul? These arguments gain more value from the fact that the evidence on the opposite side is purely negative. It is one thing to write of these controversies at a distance from the scene of the events, in the seclusion of one's own library; but quite another to study them on the spot, and to follow the events where they took place. If my readers had the opportunity of witnessing the discoveries made lately in the Cemeterium Ostrianum, and the Platonia ad Catacumbas; or of examining Grimaldi's manuscripts and drawings relating to the old basilica of Constantine; or Carrara's account of the discoveries made in 1776 in the house of Aquila and Prisca, they would surely banish from their minds the last shade of doubt.

Besides the works of Döllinger, Lightfoot, and de Rossi referred to above, there are thirty or forty which deal with the same question, as to whether S. Peter was ever at Rome. The list of them is given in volume xviii. of the "Encyclopædia Britannica," p. 696, no. 1.

Two roads issued from the bridge called Vaticanus, Neronianus, or Triumphalis, the remains of which are still seen at low water between S. Giovanni dei Fiorentini and the hospital of S. Spirito,—the Via Triumphalis, described in chapter vi., which corresponds to the modern Strada di Monte Mario, and joins the Clodia at la Giustiniana; and the Via Cornelia, which led to the woodlands west of the city, between the Via Aurelia Nova and the Triumphalis. When the apostles came to Rome, in the reign of Nero, the topography of the Vatican district, which was crossed by the Via Cornelia, was as follows:—

On the left of the road was a circus begun by Caligula, and finished by Nero; on the right a line of tombs built against the clay cliffs of the Vatican. The circus was the scene of the first sufferings of the Christians, described by Tacitus in the well-known passage of the "Annals," xv. 45. Some of the Christians were covered with the skins of wild beasts so that savage dogs might tear them to pieces; others were besmeared with tar and tallow, and burnt at the stake; others were crucified (crucibus adfixi), while Nero in the attire of a vulgar auriga ran his races around the goals. This took place a. d. 65. Two years later the leader of the Christians shared the same fate in the same place. He was affixed to a cross like the others, and we know exactly where. A tradition current in Rome from time immemorial says that S. Peter was executed inter duas metas (between the two metæ), that is, in the spina or middle line of Nero's circus, at an equal distance from the two end goals; in other words, he was executed at the foot of the obelisk which now towers in front of his great church. For many centuries after the peace of Constantine, the exact spot of S. Peter's execution was marked by a chapel called the chapel of the "Crucifixion." The meaning of the name, and its origin, as well as the topographical details connected with the event, were lost in the darkness of the Middle Ages. The memorial chapel lost its identity and was believed to belong to "Him who was crucified," that is, to Christ himself. It disappeared seven or eight centuries ago. At the same time the words inter duas metas, by which the spot was so exactly located, were deprived of their genuine significance. The name meta was generally applied to tombs of pyramidal shape; of which two were still conspicuous among the ruins of Rome: the pyramid of Caius Cestius near the Porta S. Paolo, which was called Meta Remi, and that by the church of S. Maria Traspontina, in the quarter of the Vatican which was called Meta Romuli. The consequences of this mistake were remarkable; to it we owe the erection of two noble monuments, the church of S. Pietro in Montorio, and the "Tempietto del Bramante," in the court of the adjoining convent. It seems that in the thirteenth century, when some one71 determined to raise a memorial of S. Peter's execution inter duas metas, he chose this spot on the spur of the Janiculum, because it was located at an equal distance from the meta of Romulus at la Traspontina, and that of Remus at the Porta S. Paolo!