полная версия

полная версияPagan and Christian Rome

The view from the edge of the lofty platform over the Coliseum, the Temple of Venus and Rome, and the slopes of the Palatine, is fascinating beyond conception, and as beautiful as a dream. No better place could be chosen for the study of the next class of Roman places of worship, which comprises:—

V. Pagan Monuments converted into Churches. The experience gained in twenty-five years of active exploration in ancient Rome, both above and below ground, enables me to state that every pagan building which was capable of giving shelter to a congregation was transformed, at one time or another, into a church or a chapel. Smaller edifices, like temples and mausoleums, were adapted bodily to their new office, while the larger ones, such as thermæ, theatres, circuses, and barracks were occupied in parts only. Let not the student be deceived by the appearance of ruins which seem to escape this rule; if he submits them to a patient investigation, he will always discover traces of the work of the Christians. How many times have I studied the so-called Temple of the Sibyl at Tivoli without detecting the faint traces of the figures of the Saviour and the four saints, which now appear to me distinctly visible in the niche of the cella. And again, how many times have I looked at the Temple of Neptune in the Piazza di Pietra,91 without noticing a tiny figure of Christ on the cross in one of the flutings of the fourth column on the left. It seems to me that, at one period, there must have been more churches than habitations in Rome.

I shall ask the reader to walk over the Sacra Via from the foot of the Temple of Claudius, on the ruins of which we are still sitting, to the summit of the Capitol, and see what changes time has wrought on the surroundings of this pathway of the gods.

The Coliseum, which we meet first, on our right, was bristling with churches. There was one at the foot of the Colossus of the Sun, where the bodies of the two Persian martyrs, Abdon and Sennen, were exposed at the time of the persecution of Decius. There were four dedicated to the Saviour (S. Salvator in Tellure, de Trasi, de Insula, de rota Colisei), a sixth to S. James, a seventh to S. Agatha (ad caput Africæ), besides other chapels and oratories within the amphitheatre itself.

Proceeding towards the Summa Sacra Via and the Arch of Titus we find a church of S. Peter nestled in the ruins of the vestibule of the Temple of Venus (the S. Maria Nova of later times).

Popular tradition connected this church with the alleged fall of Simon the magician,—so vividly represented in Francesco Vanni's picture, in the Vatican,—and two cavities were pointed out in one of the paving-stones of the road, which were said to have been made by the knees of the apostle when he was imploring God to chastise the impostor. The paving-stone is now kept in the church of S. Maria Nova. Before its removal from the original place it gave rise to a curious custom. People believed that rainwater collected in the two holes was a miracle-working remedy; and crowds of ailing wretches gathered around the place at the approach of a shower.

On the opposite side of the road, remains of a large church can still be seen at the foot of the Palatine, among the ruins of the baths attributed to Elagabalus. Higher up, on the platform once occupied by the "Gardens of Adonis" and now by the Vigna Barberini, we can visit the church of S. Sebastiano, formerly called that of S. Maria in Palatio or in Palladio.

I am unable to locate exactly another famous church, that of S. Cesareus de Palatio, the private chapel which Christian emperors substituted for the classic Lararium (described in "Ancient Rome," p. 127). Here were placed the images of the Byzantine princes, sent from Constantinople to Rome, to represent in a certain way their rights. The custody of these was intrusted to a body of Greek monks. Their monastery became at one time very important, and was chosen by ambassadors and envoys from the east and from southern Italy as their residence during their stay in Rome.

The basilica of Constantine is another example of this transformation. Nibby, who conducted the excavations of 1828, saw traces of religious paintings in the apse of the eastern aisle. They are scarcely discernible now.

The temple of the Sacra Urbs, and the heroön of Romulus, son of Maxentius, became a joint church of SS. Cosma and Damiano, during the pontificate of Felix IV. (526-530); the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina was dedicated to S. Lorenzo; the Janus Quadrifrons to S. Dionysius, the hall of the Senate to S. Adriano, the offices of the Senate to S. Martino, the Mamertine prison to S. Peter, the Temple of Concord to SS. Sergio e Bacco.

The same practice was followed with regard to the edifices on the opposite side of the road. The Virgin Mary was worshipped in the Templum divi Augusti, in the place of the deified founder of the empire; and also in the Basilica Julia, the northern vestibule of which was transformed into the church of S. Maria de Foro. Finally, the Ærarium Saturni transmitted its classic denomination to the church of S. Salvatore in Ærario.

In drawing sheet no. xxix. of my archæological map of Rome, which represents the region of the Sacra Via, I have had as much to do with Christian edifices as with pagan ruins.92

VI. Memorials of Historical Events. The first commemorative chapel erected in Rome is perhaps contemporary with the Arch of Constantine, and refers to the same event, the victory gained by the first Christian emperor over Maxentius in the plain of the Tiber, near Torre di Quinto.

Statue of Constantine the Great.

The existence of this chapel, called the Oratorium Sanctæ Crucis ("the oratory of the holy cross"), is frequently alluded to in early church documents. The name must have originated from a monumental cross erected on the battlefield, in memory of Constantine's vision of the "sign of Christ" (the monogram

The noble house of the Millini, to whom the Mons Vaticanus owes its present name of Monte Mario (from Mario Millini, son of Pietro and grandson of Saba), while building their villa on the highest ridge, in 1470, raised a chapel in place of the one which had been profaned, and called it Santa Croce a Monte Mario. It was held in great veneration by the Romans, who made pilgrimages to it in times of public calamities, such as the famous plague (contagio-moria) of Alexander VII. I well remember this interesting little church, before its disappearance in 1880. Its pavement, according to the practice of the time, was inlaid with inscriptions from the catacombs, whole or in fragments, twenty-four of which are now preserved in the Lipsanotheca (Palazzo del Vicario, Piazza di S. Agostino). They contain a curious list of names, like Putiolanus (so called from his birth-place, Pozzuoli) or Stercoria, a name which seems to have been taken up by devout people, as a sign of humility. Another inscription over the door of the sacristy spoke of a restoration of the building in 1696; a third, composed by Pietro and Mario Mellini in 1470, sang the praises of the cross. The most important record, however, was engraved on a slab of marble at the left of the entrance:—

"This oratory was first built in the year of the jubilee, MCCCL, by Pontius, bishop of Orvieto and vicar of the city of Rome."

The inscription, besides proving that the removal of the oratory from its original site to the summit of the mountain had been accomplished before the age of the Millini, is the only historical record of the jubilee of 1350, which attracted to Rome enormous multitudes, so that pilgrims' camps had to be provided both inside and outside the walls. Petrarca and king Louis of Hungary (then on his way back from Apulia) were among the visitors. Bishop Pontius of Orvieto, Ponzio Perotti, is also an historical man. He was intrusted with the government of the city in consequence of the attempted assassination of his predecessor, cardinal Annibaldo, by a partisan of Cola di Rienzo.

This chapel, to which so many interesting souvenirs were attached, which owed its origin to one of the greatest battles in history, which commanded one of the finest panoramas in the world, is no more. It was sacrificed in 1880 to the necessity of raising a fortress on the hill. No sign is left to mark its place.

CHAPTER IV.

IMPERIAL TOMBS. 94

The death and burial of Augustus.—His will.—The Monumentum Ancyranum.—Description and history of his mausoleum.—Its connection with the Colonnas and Cola di Rienzo.—Other members of the imperial family who were buried in it.—The story of the flight and death of Nero.—His place of burial.—Ecloge, his nurse.—The tomb of the Flavian emperors, Templum Flaviæ Gentis.—Its situation and surroundings.—The death of Domitian.—The mausolea of the Christian emperors.—The tomb and sarcophagus of Helena, mother of Constantine.—Those of Constantia.—The two rotundas built near St. Peter's as imperial tombs.—Discoveries made in them in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.—The priceless relics of Maria, wife of Honorius.—Similar instances of treasure-trove in ancient and modern times.

The Mausoleum of Augustus. Ancient writers have left detailed accounts of the last hours of the founder of the Roman Empire. On the morning of the nineteenth of August, anno Domini 14, feeling the approach of death, Augustus inquired of the attendants whether the outside world was concerned at his precarious condition; then he asked for a mirror, and composed his body for the supreme event, as he had long before prepared his mind and soul. Of his friends and the officers of the household he took leave in a cheerful spirit; and as soon as he was left alone with Livia he passed away in her arms, saying, "Livia, may you live happily, as we have lived together from the day of our marriage." His death was of the kind he had desired, peaceful and painless. Ευθανασιαν (an easy end) was the word he used longingly, whenever he heard of any one dying without agony. Once only in the course of the malady he seemed to lose consciousness, when he complained of forty young men crowding around the bed to steal away his body. More than a wandering mind, Suetonius thinks this was a vision or premonition of an approaching event, because forty prætorian soldiers were really to carry the bier in the funeral march. The great man died at Nola, in the same villa and room in which his father, Octavius, had passed away years before. His body was transported from village to village, from city to city, along the Appian Way, by the members of each municipal council in turn; and, to avoid the intense heat of the Campanian and Pontine lowlands, the procession marched only at night, the bier being kept in the local sanctuaries or town halls during the day. Thus Bovillae (le Frattocchie, at the foot of the Alban hills) was reached. The whole Roman knighthood was here in attendance; the body was carried in triumph, as it were, over the last ten miles of the road, and deposited in the vestibule of the palace on the Palatine Hill.

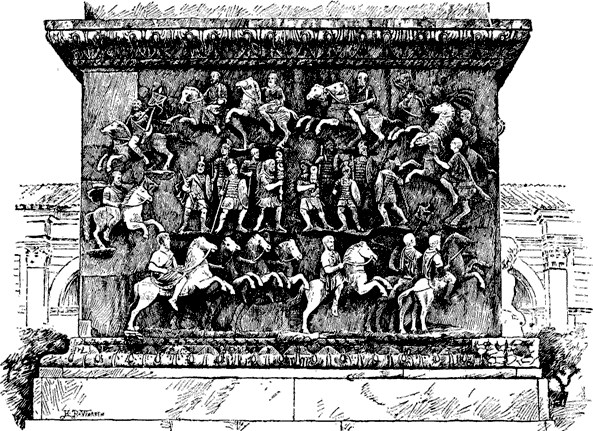

Military funeral evolutions; from the base of the Column of Antoninus.

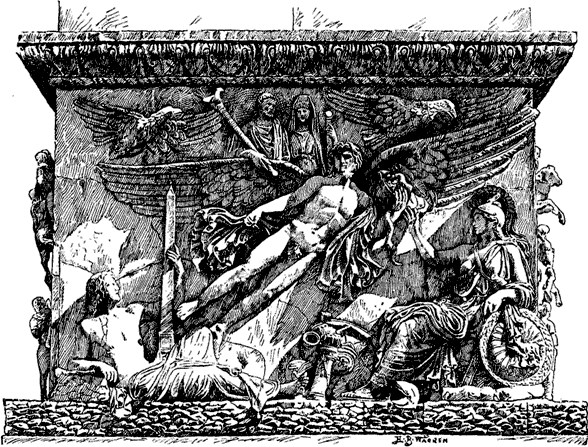

Meanwhile proposals were made and resolutions passed in the Senate, which went far beyond anything that had ever been suggested in such contingencies of state. One of the members recommended that the statue of Victory which stood in the Curia should be carried before the hearse, that lamentations should be sung by the sons and daughters of the senators, and that the pageant, on its way to the Campus Martius, should march through the Porta Triumphalis, which was never opened except to victorious generals. Another member suggested that all classes of citizens should put aside their golden ornaments and all articles of jewelry, and wear only iron finger-rings; a third, that the name of "August" should be transferred to the month of September, because the lamented hero was born in the latter and had died in the former. These exaggerated expressions of grief were suppressed, however, and the funeral was organized with the grandest simplicity. The body was placed in the Forum, in front of the Temple of Julius Cæsar, from the rostra of which Tiberius read a panegyric. Another oration was delivered at the opposite end of the Forum by Drusus, the adopted son of Tiberius. Then the senators themselves placed the bier on their shoulders, leaving the city by the Porta Triumphalis. The procession formed by the Senate, the high priesthood, the knights, the army, and the whole population skirted the Circus Flaminius and the Septa Julia, and by the Via Flaminia reached the ustrinum, or sacred enclosure for cremation. As soon as the body had been placed on the pyre the "march past" began in the same order, the officers and men of the various army corps making their evolutions or decursiones. This word, taken in a general sense, means a long march by soldiers made in a given time and without quitting the ranks; when referring to a funeral ceremony it signifies special evolutions performed three times, in honor of distinguished generals. A decursio is represented on the base of the column of Antoninus Pius, now in the Giardino della Pigna. In that which I am describing, officers and men threw on the pyre the decorations which Augustus had awarded them for their bravery in battle. The privilege of setting fire to the rogus was granted to the captains of the legions whom he had led so often to victory. They approached with averted faces, and, uttering a last farewell, performed their act of duty and respect. The cremation accomplished, and while the glowing embers were being extinguished with wine and perfumed waters, an eagle rose from the ashes as if carrying the soul of the hero to Heaven. Livia and a few officers watched the place for five days and nights, and finally collected the ashes in a precious urn, which they placed in the innermost crypt of the mausoleum which Augustus had built in the Campus Martius forty-two years before.

The Apotheosis of an Emperor; from the base of the Column of Antoninus.

Of this monument we have a description by Strabo, and ruins which substantiate the description in its main lines. It was composed of a circular basement of white marble, two hundred and twenty-five feet in diameter, which supported a cone of earth, planted with cypresses and evergreens. On the top of the mound the bronze statue of the emperor towered above the trees.

This type of sepulchral structure dates almost from prehistoric times, and was in great favor with the Etruscans. The territories of Vulci, near the Ponte dell' Abbadia, and of Veii, near the Vaccareccia, are dotted with these mounds, which the peasantry call cocumelle. Augustus made the type popular among the Romans, as is proved by the large number of tumuli which date from his age, on the Via Salaria, the Via Labicana, and the Via Appia.

His tomb was entered from the south, the entrance being flanked by monuments of great interest, such as the obelisks now in the Piazza del Quirinale and the Piazza di S. Maria Maggiore; the copies of the decrees of the Senate in honor of the personages buried within; and, above all, the Res gestæ divi Augusti, a sort of political will, autobiography, and apology, the importance of which surpasses that of any other document relating to the history of the Roman Empire.

This was written by Augustus towards the end of his life. He ordered his executors to have it engraved on bronze pillars on each side of the entrance to his mausoleum. That his will was duly executed by Livia, Tiberius, Drusus, and Germanicus, his heirs and trustees, is proved by the frequent allusions to the document made by Suetonius and Velleius, and also by the copies which have come down to us, not from Rome or Italy, but from the remote provinces of Galatia and Pisidia.

It was customary in ancient times to raise temples in honor of the rulers of the empire, and to ornament them with their images and eulogies. These were called Augustea or ædes Augusti et Romæ in the western provinces, σεβαστεια in eastern or Greek-speaking countries,95 Ancyra (Angora), the capital of Galatia, and Apollonia, the capital of Pisidia, were the foremost among the Asiatic cities to pay this honor to the founder of the empire.

The Ancyran temple owes its preservation to the Christians, who made use of it as a church from the fourth to the fifteenth centuries, and also to the Turks, who have turned it into a mosque associated with the Hadji Beiram. The temple and its invaluable epigraphic treasures became known towards the middle of the sixteenth century. In 1555 an embassy was sent by the emperor Ferdinand II. to Suleiman, the khalif, who was then residing at Amasia.96 It so happened that the head of the mission, Ogier Ghislain Busbecq, and his assistant, Antony Wrantz, bishop of Agram, were fond of archæological investigation. They were struck by the importance of the Augusteum at Ancyra; and with the help of their secretaries, they made a tolerably good copy of its inscriptions. Since 1555 the place has been visited many times, notably by Edmond Guillaume, in 1861, and by Humann, in 1882.97 There are two copies of the will of Augustus engraved on the marble wall of the temple: one in Latin, which is in the pronaos, on either side of the door; the other in Greek, on the outer wall of the cella. Both were transcribed (or translated) "from the original, engraved on the bronze pillars at the mausoleum in Rome." The document is divided into three parts, and thirty-five paragraphs. The first part describes the honors conferred on Augustus,—military, civil, and sacerdotal; the second gives the details of the expenses which he sustained for the benefit and welfare of the public; the third relates his achievements in peace and war; and some of the facts narrated are truly remarkable. He says, for instance, that the Roman citizens who fought under his orders and swore allegiance to him numbered five hundred thousand, and that more than three hundred thousand completed the term of their engagement, and were honorably dismissed from the army. To each of these he gave either a piece of land, which he bought with his own money, or the means of purchasing it in other lands than those assigned to military colonies. Since, at the time of his death, one hundred and sixty thousand Roman citizens were still serving under the flag, the number of those killed in battle, disabled by disease, or dismissed for misconduct, in the course of fifty-five years98 is reduced to forty thousand. The percentage is surprisingly low, considering the defective organization of the military medical staff, and the length and hardships of the campaigns which were conducted in Italy (Mutina), Macedonia (Philippi), Acarnania (Actium), Sicily, Egypt, Spain, Germany, Armenia and other countries. The number of men-of-war of large tonnage, which were captured, burnt, or sunk in battle, is stated at six hundred. In the naval engagement against Sextus Pompeius, off Naulochos, he sank twenty-eight vessels, and captured or burnt two hundred and fifty-five; so that only seventeen out of a powerful fleet of three hundred could make their escape.

Thrice he took the census of the citizens of Rome; the first time in the year 29-28 b. c., when 4,063,000 souls were counted; the second in the year 8 b. c., showing 4,233,000; the third in 14 a. d., with 4,937,000. Under his peaceful rule, therefore, there was an increase of 874,000 in the number of Roman citizens. He remarks with pride that, while from the beginning of the history of Rome to his own age the gate of the Temple of Janus had been shut but twice, as a sign that peace was prevailing over land and sea, he had been able to close it three times in the course of fifty years. His liberalities are equally surprising. Sometimes they took the form of free distributions of corn, oil, or wine; sometimes of an allowance of money. He asserts that he spent in gifts the sum of six hundred and twenty millions of sestertii, nearly twenty-six millions of dollars. Adding to this sum the cost of purchasing lands for his veterans in Italy (six hundred millions) and in the provinces (two hundred and sixty millions), of giving pecuniary rewards to his veterans (four hundred millions), of helping the public treasury (one hundred and fifty millions), and the army funds (one hundred and seventy millions), besides other grants and bounties, the amount of which is not known, we reach a total expenditure for the benefit of his people of ninety-one million dollars.

I need not speak of the material renovation of the city, which he found of brick and left of marble. Roads, streets, aqueducts, bridges, quays, places of amusement, places of worship, parks, gardens, public offices, were built, opened, repaired, and decorated with incredible profusion. Suetonius says that, on one occasion alone, he offered to Jupiter Capitolinus sixteen thousand pounds of gold and fifty millions' worth of jewels. In the year 28 b. c. not less than eighty-two temples were rebuilt in Rome itself.

Were we not in the presence of official statistics and of state documents, we should hardly feel inclined to believe these enormous statements. We must remember, too, that the work of Augustus was seconded and imitated with equal magnitude by his wealthy friends and advisers, Marcius Philippus, Lucius Cornificius, Asinius Pollio, Munatius Plaucus, Cornelius Balbus, Statilius Taurus, and above all by Marcus Agrippa, to whom we owe the aqueducts of the Virgo and Julia, the Pantheon, the Thermæ, the artificial lake (stagnum), the Portico of the Argonauts, the Temple of Neptune, the Portico of Vipsania Palta, the Diribitorium, the Septa, the Campus Agrippæ, a bridge on the Tiber, and hundreds of other costly structures. During the twelve months of his ædileship, in 19 b. c., he rebuilt the network of the city sewers, adding many miles of new channels, erected eight hundred and five fountains, and one hundred and thirty water reservoirs. These edifices were ornamented with three hundred bronze and marble statues, and four hundred columns.