полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

HABITAT.—South India.

DESCRIPTION.—"Ears moderately large; form somewhat elongated; tail very short, concealed; feet and limbs very small; head and ears nude, sooty-coloured; belly very thinly clad with yellowish hairs; spines ringed dark brown and whitish, or whitish with a broad brown sub-terminal ring, tipped white."—Jerdon.

SIZE.—Head and body about 6 inches. Dr. Anderson considers this as identical with E. collaris.

NO. 152. ERINACEUS PICTUSThe Painted HedgehogHABITAT.—Central India, Goona, Ulwar, Agra, Kurrachee.

DESCRIPTION.—Similar to the above, but the tips of the spines are more broadly white, and the brown bands below not so dark; the ears are somewhat larger than micropus, and the feet narrower and not so long.

NO. 153. ERINACEUS GRAYIHABITAT.—North-west India.

DESCRIPTION.—The general colour is blackish-brown; the spines are narrowly tipped with black, succeeded by a narrowish yellow band; then a blackish-brown band, the rest of the spine being yellowish; the broad dark-brown band is so strongly developed as to give the animal its dark appearance when viewed from the side; some animals are, however, lighter than others. The feet are large; the fore-feet broad, somewhat truncated, with moderately long toes and powerful claws.

SIZE.—Head and body about 6¾ inches.

NO. 154. ERINACEUS BLANFORDI (Anderson)HABITAT.—Sind, where one specimen was obtained by Mr. W. T. Blanford, at Rohri.

DESCRIPTION.—Muzzle rather short, not much pointed; ears moderately large, but broader than long, and rounded at the tips; feet larger and broader than in the next species, with the first toe more largely developed than in the last. The spines meet in a point on the forehead, and there is no bare patch on the vertex. Each spine is broadly tipped with deep black, succeeded by a very broad yellow band, followed by a dusky brown base; fur deep brown; a few white hairs on chin and anterior angle of ear.

SIZE.—Head and body, 5·36 inches.

NO. 155. ERINACEUS JERDONI (Anderson)HABITAT.—Sind, Punjab frontier.

DESCRIPTION.—Muzzle moderately long and pointed; ears large, round at tip and broad at base; feet large, especially the fore-feet; claws strong. The spines begin on a line with the anterior margins of the ears; large nude area on the vertex; spines with two white and three black bands, beginning with a black band. When they are laid flat the animal looks black; but an erection the white shows and gives a variegated appearance.

SIZE.—Head and body about 7½ inches.

NO. 156. ERINACEUS MEGALOTISThe Large-eared HedgehogHABITAT.—Afghanistan.

More information is required about this species. Jerdon seems to think it may be the same as described by Pallas (E. auritus), which description I have before me now ('Zoographica Rosso Asiatica,' vol. i. page 138), but I am unable to say from comparison that the two are identical—the ears and the muzzle are longer than in the common hedgehog. This is the species which he noticed devouring blistering beetles with impunity. It has a very delicate fur of long silky white hairs, covering the head, breast and abdomen, "forming also along the sides a beautiful ornamental border" (Horsfield, from a specimen brought from Mesopotamia by Commander Jones, I.N.)

The space to which I am obliged to limit myself will not allow of my describing at greater length; but to those of my readers who are interested in the Indian hedgehogs, I recommend the paper by Dr. J. Anderson in the 'Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal' for 1878, page 195, with excellently drawn plates of the heads, skulls and feet of the various species. There is one peculiarity which he notices regarding the skull of E. collaris (or, as he calls it, micropus): the zygomatic arch is not continuous as in the other species, but is broken in the middle, the gap being caused by the absence of the malar or cheek-bone. In this respect it resembles, though Dr. Anderson does not notice it, the Centetidæ or Tanrecs of Madagascar.

Dr. Anderson's classification is very simple and good. He has two groups: the first, containing E. micropus and E. pictus, is distinguished by the second upper premolar simple, one-fanged, the feet club-shaped; soles tubercular. The second group, containing E. Grayi, E. Blanfordi and E. Jerdoni, has the second upper premolar compound, three-fanged, and the feet well developed and broad. The first group has also a division or bare area on the vertex; the second has not.

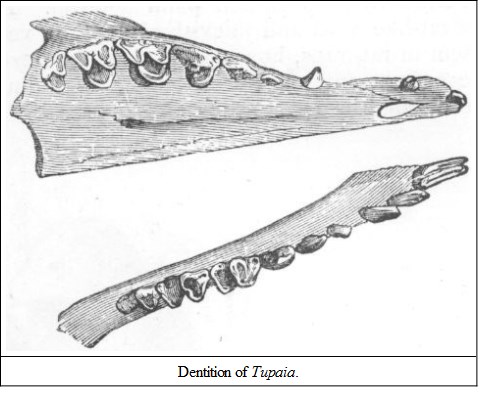

FAMILY HYLOMIDÆ (Anderson)The following little animal has affinities to both Erinaceidæ and Tupaiidæ, and therefore it may appropriately be placed here. Dr. Anderson on the above ground has placed it in a separate family, otherwise it is generally classed with the Erinaceidæ. Its skull has the general form of the skull of Tupaia, but in its imperfect orbit, in the rudiment of a post-orbital process, and in the absence of any imperfections of the zygomatic arch and in the position of the lachrymal foramen it resembles the skull of Erinaceus. The teeth are 44 in number: Inc., 3—3/3—3; can., 1—1/1—1; premolars, 4—4/4—4; molars, 3—3/3—3, and partake of the character of both Tupaia and Erinaceus. The shank-bones being united and the rudimentary tail create an affinity to the latter, whilst its arboreal habits are those of the former.

GENUS HYLOMYSHead elongate; ears round; feet arboreal, naked below; tail semi-nude; pelage not spiny.

NO. 157. HYLOMYS PEGUENSISThe Short-tailed Tree-ShrewHABITAT.—Burmah, Pegu, Ponsee in the Kakhyen hills.

Appears to be identical with the species from Borneo (H. suillus).

FAMILY TUPAIIDÆThese interesting little animals were first accurately described about the year 1820, though, as I have before stated, it was noticed in the papers connected with Captain Cook's voyages, but was then supposed to be a squirrel. Sir T. Stamford Raffles writes: "This singular little animal was first observed tame in the house of a gentleman at Penang, and afterwards found wild at Singapore in the woods near Bencoolen, where it lives on the fruit of the kayogadis, &c." Another species, T. Javanica, had, however, been discovered in Java fourteen years before, but not published till 1821. They are sprightly little creatures, easily tamed, and, not being purely insectivorous, are not difficult to feed in captivity. Sir T. S. Raffles describes one that roamed freely all over the house, presenting himself regularly at meal-times for milk and fruit. Dr. Sal. Müller describes the other species (T. Javanica) as a confiding, simple little animal, always in motion, seeking its food at one time amongst dry leaves and moss on the ground, and again on the stems and branches of trees, poking its nose into every crevice. Its nest, he says, is formed of moss at some height from the ground, supported on clusters of orchideous plants. Dr. Cantor, in his 'Catalogue of the Mammalia of the Malayan Peninsula,' writes as follows: "In a state of nature it lives singly or in pairs, fiercely attacking intruders of its own species. When several are confined together they fight each other, or jointly attack and destroy the weakest. The natural food is mixed insectivorous and frugivorous. In confinement, individuals may be fed exclusively on either, though preference is evinced for insects; and eggs, fish and earth-worms are equally relished. A short, peculiar, tremulous, whistling sound, often heard by calls and answers in the Malayan jungle, marks their pleasurable emotions, as for instance on the appearance of food, while the contrary is expressed by shrill protracted cries. Their disposition is very restless, and their great agility enables them to perform the most extraordinary bounds in all directions, in which exercise they spend the day, till night sends them to sleep in their rudely-constructed lairs in the highest branches of trees. At times they will sit on their haunches, holding their food between their forelegs, and after feeding they smooth the head and face with both fore-paws, and lick the lips and palms. They are also fond of water, both to drink and to bathe in. The female usually produces one young."

The above description reminds one forcibly of the habits of squirrels, so it is no wonder that at one time these little creatures were confounded with the Sciuridæ.

GENUS TUPAIAThe dentition of this genus is as follows: Either four or six incisors in the upper jaw, but always six in the lower; four premolars and three molars in each jaw, upper and lower. The skull has a complete bony orbit, and the zygomatic arch is also complete, but with a small elongated perforation; the muzzle attenuated, except in T. Ellioti; ears oval; the stomach possesses a cæcum or blind gut; the eyes are large and prominent, and the tail bushy, like that of a squirrel; the toes are five in number, with strong claws; the shank-bones are not united as in the hedgehogs. The diet is mixed insectivorous and frugivorous.

NO. 158. TUPAIA ELLIOTIElliot's Tree-Shrew (Jerdon's No. 87)HABITAT.—Southern India, Godavery district, Cuttack; the Central Provinces, Bhagulpore range.

DESCRIPTION.—Fur pale rufous brown, darker on the back and paler on the sides; the chin, throat, breast and belly yellowish, also a streak of the same under the tail; the upper surface of the tail is of the same colour as the centre of the back; there is a pale line from the muzzle over the eye, and a similar patch beneath it; the fur of this species is shorter and more harsh, and the head is more blunt than in the Malayan members of the family.

SIZE.—Head and body, 7 to 8 inches; tail, 7 to 9 inches.

NO. 159. TUPAIA PEGUANA Syn.—TUPAIA BELANGERIThe Pegu Tree-Shrew (Jerdon's No. 88)HABITAT.—Sikim (Darjeeling), Assam and through Arakan to Tenasserim.

DESCRIPTION.—Jerdon says: "General hue a dusky greenish-brown, the hairs being ringed brown and yellow; lower parts the same, but lighter; and with a pale buff line; a stripe from the throat to the vent, broadest between the forearms and then narrowing; ears livid red, with a few short hairs; palms and soles dark livid red." Dr. Anderson remarks that the fur is of two kinds of hairs—one fine and wavy at the extremity, banded with black, yellow and black; the second being strong and somewhat bristly, longer than the other, and banded with a black basal half and then followed by rings of yellow and black, then yellow again with a black tip, the black basal half of the hairs being hidden, the annulation of the free portions produces a rufous olive-grey tint over the body and tail.

SIZE.—Head and body about 7 inches; tail, 6½.

Jerdon says of it that those he procured at Darjeeling frequented the zone from 3000 to 6000 feet; they were said by the natives to kill small birds, mice, &c. The Lepcha name he gives is Kalli-tang-zhing. McMaster in his notes writes: "The Burmese Tupaia is a harmless little animal; in the dry season living in trees and in the monsoon freely entering our houses, and in impudent familiarity taking the place held in India by the common palm squirrel. It is, however, probably from its rat-like head and thievish expression, very unpopular. I have found them in rat-traps, however, so possibly they deserve to be so." He adds he cannot endorse the statement regarding their extraordinary agility mentioned by Dr. Cantor and quoted by Jerdon, for he had seen his terriers catch them, which they were never able to do with squirrels; and cats often seize them.

Mason says: "One that made his home in the mango-tree near my house at Tonghoo made himself nearly as familiar as the cat. Sometimes I had to drive him off the bed, and he was very fond of putting his nose into the teacups immediately after breakfast, and acquired a taste both for tea and coffee. He lost his life at last by incontinently walking into a rat-trap."

The Burmese name for it is Tswai in Arracan. Jerdon states that it is one of the few novelties that had escaped the notice of Mr. Brian Hodgson, but Dr. Anderson mentions a specimen (unnamed) from Nepal in the British Museum which was obtained by Hodgson.

NO. 160. TUPAIA CHINENSIS (Anderson)HABITAT.—Burmah, Kakhyen hills, east of the valley of the Irrawaddy.

DESCRIPTION.—Ferruginous above, yellowish below, the basal two-thirds of the hair being blackish, succeeded by a yellow, a black, and then a yellow and black band, which is terminal; there is a faint shoulder streak washed with yellowish; the chest pale orange yellow, which hue extends along the middle of the belly as a narrow line; under surfaces of limbs grizzled as on the back, but paler; upper surface of tail concolorous with the dorsum.

SIZE.—Head and body, 6½ inches; tail, 6·16.

The teeth are larger than those of T. Ellioti, but smaller than the Malayan T. ferruginea, and the skull is smaller than that of the last species, and the teeth are also smaller. Dr. Anderson says: "When I first observed the animal it was on a grassy clearing close to patches of fruit, and was so comporting itself that in the distance I mistook it for a squirrel. The next time I noticed it was in hedgerows."

The other varieties of Tupaia belong to the Malayan Archipelago—T. ferruginea, T. tana, T. splendidula, and T. Javanica to Borneo and Java. There is one species which inhabits the Nicobars.

NO. 161. TUPAIA NICOBARICAHABITAT.—Nicobar Island.

DESCRIPTION.—Front and sides of the face, outside of fore-limbs, throat and chest, golden yellow; inner side of hind limbs rich red brown, which is also the colour of the hind legs and feet; head dark brown, with golden hairs intermixed; back dark maroon, almost black; upper surface of the tail the same; pale oval patch between shoulders, dark band on each side between it and fore-limbs, passing forward over the ears.

SIZE.—Head and body, 7·10; tail, 8 inches.

There is a little animal allied to the genus Tupaia, which has hitherto been found only in Borneo and Sumatra, but as Sumatran types have been found in Tenasserim, perhaps some day the Ptilocercus Lowii may be discovered there. It has a rather shorter head than the true Banxrings, more like T. Ellioti, but its dentition is nearly the same, as also are its habits. Its chief peculiarity lies in its tail, which is long, slender and naked, like that of a rat for two-thirds of its length, the terminal third being adorned with a broad fringe of hair on each side, like the wings of an arrow or the plumes of a feather. There is an excellent coloured picture of it in the 'Proc. Zool. Society,' vol. of Plates.

I had almost concluded my sketch of the Insectivora without alluding to one most interesting genus, which ought properly to have come between the shrews and the hedgehogs, the Gymnura, which, though common in the Malay countries, has only recently been found in Burmah—a fact of which I was not aware till I saw it included in a paper on Tenasserim mammals by Mr. W. T. Blanford ('Jour. As. Soc. Beng.,' 1878, page 150). Before I refer to his notes I may state that this animal is a sort of link between the Soricidæ and the Erinaceidæ, and De Blainville proposed for it the generic name of Echinosorex, but the one generally adopted is Gymnura, which was the specific name given to it by its discoverer, Sir Stamford Raffles, who described it as a Viverra (V. gymnura); however, Horsfield and Vigors and Lesson, the two former in England and the latter in France, saw that it was not a civet, and, taking the naked tail as a peculiarity, they called the genus Gymnura, and the specimen Rafflesii. There is not much on record regarding the anatomy of the animal, and in what respects it internally resembles the hedgehogs. Outwardly it has the general soricine form, though much larger than the largest shrew. The long tail too is against its resemblance to the hedgehogs, which rests principally on its spiny pelage.

The teeth in some degree resemble Erinaceus, the molars and premolars especially, but the number in all is greater, there being forty-four, or eight more. It would be interesting to know whether the zygomatic arch is perfect and the tibia and fibula united, as in the hedgehogs, or wanting and distinct as in the shrews. I have given a slight sketch in outline of the animal.

NO. 162. GYMNURA RAFFLESIIThe BulauHABITAT.—Tenasserim (Sumatra, Borneo); Malacca.

DESCRIPTION.—Long tapering head, with elongated muzzle, short legs, shrew-like body, with a long, round, tapering and scaly rat-like tail, naked, with the exception of a few stiff hairs here and there among the scales. In each jaw on each side three incisors, one canine (those in the upper jaw double-fanged) and seven premolars and molars; feet five-toed, plantigrade, armed with strong claws. Fur of two kinds, fine and soft, with longer and more spiny ones intermixed. The colour varies a good deal, the general tint being greyish-black, with head and neck pale or whitish, and with a broad black patch over the eye. Some have been found almost wholly white, with the black eye-streak and only a portion of the longer hairs black, so that much stress cannot be laid on the colouring; the tail is blackish at the base, whitish and compressed at the tip. Mr. Blanford says: "The small scales covering the tail are indistinctly arranged in rings and sub-imbricate; on the lower surface the scales are convex and distinctly imbricate, the bristles arising from the interstices. Thus the under surface of the tail is very rough, and may probably be of use to the animal in climbing." He also refers to the fact that the claws of his specimen are not retractile, and mentions that in the original description both in Latin and English the retractability of the claws is pointed out as a distinction between Gymnura and Tupaia. In the description given of the Sumatran animal both by Dallas and Cuvier nothing is mentioned about this feature.

SIZE.—A Sumatran specimen: head and body, 14 inches; tail, 12 inches. Mr. Blanford's specimen: head and body, 12 inches; tail, 8·5.

Mr. Blanford was informed by Mr. Davison, who obtained it in Burmah, that the Gymnura is purely nocturnal in its habits, and lives under the roots of trees. It has a peculiar and most offensive smell, resembling decomposed cooked vegetables. The Bulau has not the power of rolling itself up like the hedgehog, nor have the similar forms of insectivores which resemble the hedgehog in some respects, such as the Tenrecs (Centetes), Tendracs (Ericulus), and Sokinahs (Echinops) of Madagascar.

CARNIVORASpeaking generally, the whole range of mammals between the Quadrumana and the Rodentia are carnivorous with few exceptions, yet there is one family which, from its muscular development and dentition, is pre-eminently flesh-eating, as Cuvier aptly remarks, "the sanguinary appetite is combined with the force necessary for its gratification." Their forms are agile and muscular; their circulation and respiration rapid. As Professor Kitchen Parker graphically writes: "This group, which comprises all the great beasts of prey, is one of the most compact as well as the most interesting among the mammalia. So many of the animals contained in it have become 'familiar in our mouths as household words,' bearing as they do an important part in fable, in travel, and even in history; so many of them are of such wonderful beauty, so many of such terrible ferocity, that no one can fail to be interested in them, even apart from the fact likely to influence us more in their favour than any other, that the two home pets, which of all others are the commonest and the most interesting, belong to the group. No one who has had a dog friend, no one who has watched the wonderful instance of maternal love afforded by a cat with her kittens, no one who loves riding across country after a fox, no lady with a taste for handsome furs, no boy who has read of lion and tiger hunts and has longed to emulate the doughty deeds of the hunter, can fail to be interested in an assemblage which furnishes animals at once so useful, so beautiful and so destructive. It must not be supposed from the name of this group that all its members are exclusively flesh-eaters, and indeed it will be hardly necessary to warn the reader against falling into this mistake, as there are few people who have never given a dog a biscuit, or a bear a bun. Still both the dog and several kinds of bears prefer flesh-meat when they can get it, but there are some bears which live almost exclusively on fruit, and are, therefore, in strictness not carnivorous at all. The name must, however, be taken as a sort of general title for a certain set of animals which have certain characteristics in common, and which differ from all other animals in particular ways." I would I had more space at my disposal for further quotations from Professor Parker's 'General Remarks on the Land Carnivora,' his style is so graphic.

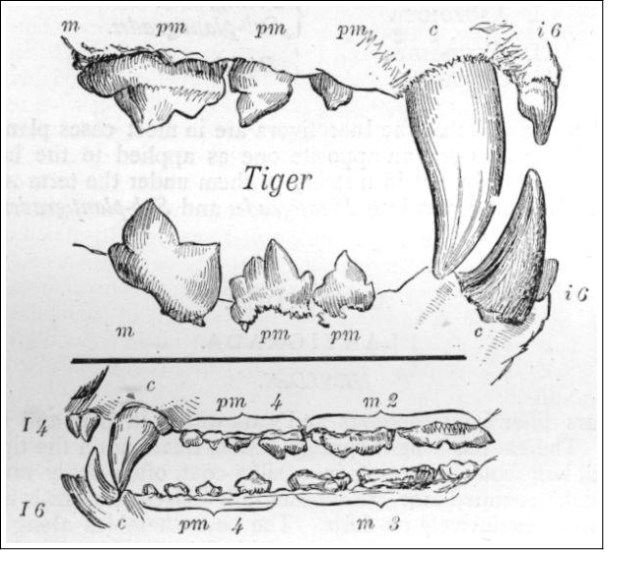

The dentition of the Carnivora varies according to the exclusiveness of their fleshy diet, and the nature of that diet.

In taking two typical forms I give below sketches from skulls in my possession of the tiger, and the common Indian black bear; the one has trenchant cutting teeth which work up and down, the edges sliding past each other just like a pair of scissors; the other has flat crowned molars adapted for triturating the roots and herbage on which it feeds. A skull of an old bear which I have has molars of which the crowns are worn almost smooth from attrition. In the most carnivorous forms the tubercular molars are almost rudimentary.

The skull exhibits peculiar features for the attachment of the necessary powerful muscles. The bones of the face are short in comparison with the cranial portion of the skull (the reverse of the Herbivores); the strongly built zygomatic arch, the roughened ridges and the broad ascending ramus of the lower jaw, all afford place for the attachment of the immense muscular development. Then the hinge of the jaw is peculiar; it allows of no lateral motion, as in the ruminants; the condyle, or hinge-bolt of a tiger's jaw (taken from the largest in my collection), measures two inches, and as this fits accurately into its corresponding (glenoid) cavity, there can be no side motion, but a vertical chopping one only. The skeleton of a typical carnivore is the perfection of strength and suppleness. The tissue of the bones is dense and white; the head small and beautifully articulated; the spine flexible yet strong. In those which show the greatest activity, such as the cats, civets and dogs, the spinous processes, especially in the lumbar region, are greatly developed—more so than in the bears. These serve for the attachment of the powerful muscles of the neck and back. The clavicle or collar-bone is wanting, or but rudimentary. The stomach is simple; the intestinal canal short; liver lobed; organs of sight, hearing, and smell much developed.

Now we come to the divisions into which this group has been separated by naturalists. I shall not attempt to describe the various systems, but take the one which appears to me the simplest and best to fit in with Cuvier's general arrangement, which I have followed. Modern zoologists have divided the family into two great groups—the Fissipedia (split-feet) or land Carnivora, and the Pinnipedia (fin-feet) or water Carnivora. Of the land Carnivora some naturalists have made the following three groups on the characteristics of the feet, viz., Plantigrada, Sub-plantigrada and Digitigrada. The dogs and cats, it is well known, walk on their toes—they are the Digitigrada; the bears and allied forms on the palms of their hands and soles of their feet, more or less, and thus form the other two divisions, but there is another classification which recommends itself by its simplicity and accuracy. Broadly speaking, there are three types of land carnivores—the cat, the dog, and the bear, which have been scientifically named Æluroidea (from the Greek ailouros, a cat); Cynoidea (from kuon, a dog); and Arctoidea (from arctos, a bear). The distinction is greater between the families of Digitigrades, the cat and dog, than between the Plantigrades and Sub-plantigrades, and therefore I propose to adopt the following arrangement:—