полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

I may here remark that the Insectivora are in most cases plantigrade, therefore the term is not an apposite one as applied to the bear and bear-like animals only, but in treating of them under the term Arctoidea we may divide them again into Plantigrades and Sub-plantigrades.

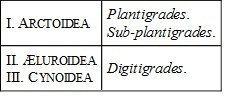

ARCTOIDEAPLANTIGRADAURSIDÆ

The bears differ from the dogs and cats widely in form and manner, and diet. The cat has a light springy action, treading on the tips of its toes, a well-knit body glistening in a silky coat, often richly variegated, "a clean cut," rounded face, with beautifully chiselled nostrils and thin lips, and lives exclusively on flesh. The bear shambles along with an awkward gait, placing the entire sole of his foot on the ground; he has rough dingy fur, a snout like a pig's, and is chiefly a vegetarian—and in respect to this last peculiarity his dentition is modified considerably: the incisors are large, tri-cuspidate; the canines somewhat smaller than in the restricted carnivora; these are followed by three small teeth, which usually fall out at an early period, then comes a permanent premolar of considerable size, succeeded by two molars in the upper, and three in the under jaw. The dental formula is therefore: Inc., 3—3/3—3; can., 1—1/1—1; premolars, 4—4/4—4; molars, 2—2/3—3. In actual numbers this formula agrees with that for the dogs; but the form of the teeth is very different, inasmuch as the large premolars and the molars have flat tuberculated crowns, constituting them true grinders, instead of the trenchant shape of the cats, which is also, to a modified extent, possessed by the dogs, of which the last two molars have, instead of cutting edges, a grinding surface with four cusps. The trenchant character is entirely lost in the bear, even in the carnivorous species which exhibit no material difference in the teeth, any more than, as I mentioned at the commencement of this work, do the teeth of the human race, be they as carnivorous as the Esquimaux, or vegetarian as the Hindu.

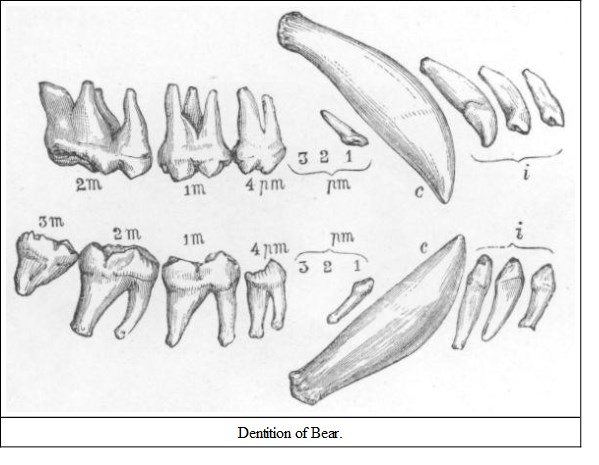

There is also another peculiarity in the bear's skull as compared with the cat's. In the latter there is a considerable bulging below the aperture of the ear called the bulla tympani, or bulb of the drum. This is almost wanting in the bear, and it would be interesting to know whether this much affects its hearing. I myself am of opinion that bears are not acute in this sense, but then my experience has been with the common Indian Ursus, or Melursus labiatus only, and the skulls of this species in my possession strongly exhibit this peculiarity.6 The cylindrical bones resemble those of man nearer than any other animal, the femur especially; and a skinned bear has a most absurd resemblance to a robust human being. The sole of the hind foot leaves a mark not unlike that of a human print.

The Brown Bear of Europe (Ursus arctos) is the type of the family, and has been known from the earliest ages—I may say safely prehistoric ages, for its bones have been frequently found in post-pliocene formations along with those of other animals of which some are extinct. An extinct species of bear, Ursus spelæus, commonly called the Cave Bear, seems to have been the ancestor of the Brown Bear which still is found in various parts of Europe, and is said to have been found within historic times in Great Britain.

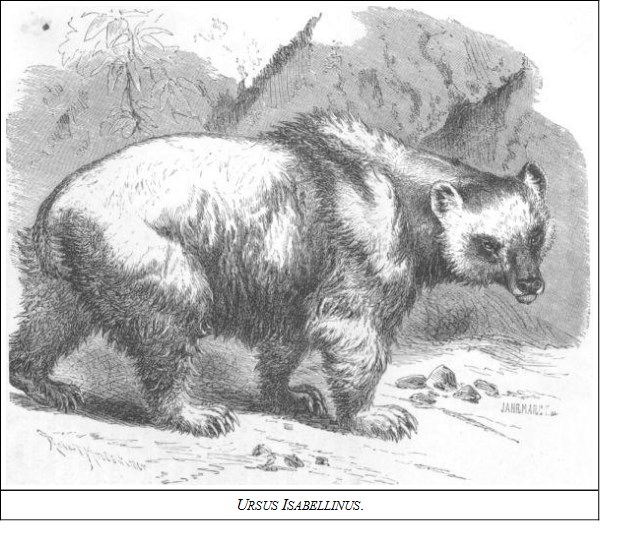

The bear of which we have the oldest record is almost the same as our Indian Brown or Snow Bear. Our bear (U. Isabellinus) is but a variety of U. Syriacus, which was the one slain by David, and is spoken of in various parts of the Bible. It is the nearest approach we have to the European U. arctos.

GENUS URSUSNO. 163. URSUS ISABELLINUSThe Himalayan Brown Bear (Jerdon's No. 89)NATIVE NAME.—Barf-ka-rich or Bhalu, Hind.; Harput, Kashmiri; Drin-mor, Ladakhi.

DESCRIPTION.—A yellowish-brown colour, varying somewhat according to sex and time of year. Jerdon says: "In winter and spring the fur is long and shaggy, in some inclining to silvery grey, in others to reddish brown; the hair is thinner and darker in summer as the season advances, and in autumn the under fur has mostly disappeared, and a white collar on the chest is then very apparent. The cubs show this collar distinctly. The females are said to be lighter in colour than the males."

Gray does not agree in the theory that Ursus Syriacus is the same as this species; in external appearance he says it is the same, but there are differences in the skull; the nose is broader, and the depression in the forehead less. The zygomatic arch is wider and stronger; the lower jaw stronger and higher, and the upper tubercular grinders shorter and thicker than in Ursus Isabellinus.

"It is found," Jerdon says, "only on the Himalayas and at great elevations in summer close to the snow. In autumn they descend lower, coming into the forests to feed on various fruits, seeds, acorns, hips of rose-bushes, &c., and often coming close to villages to plunder apples, walnuts, apricots, buckwheat, &c. Their usual food in spring and summer is grass and roots. They also feed on various insects, and are seen turning over stones to look for scorpions (it is said) and insects that harbour in such places. In winter they retreat to caves, remaining in a state of semi-torpidity, issuing forth in March and April. Occasionally they are said to kill sheep or goats, often wantonly, apparently, as they do not feed upon them. They litter in April and May, the female having generally two cubs. This bear does not climb trees well."

The next three species belong to the group of Sun Bears; Helarctos of some authors.

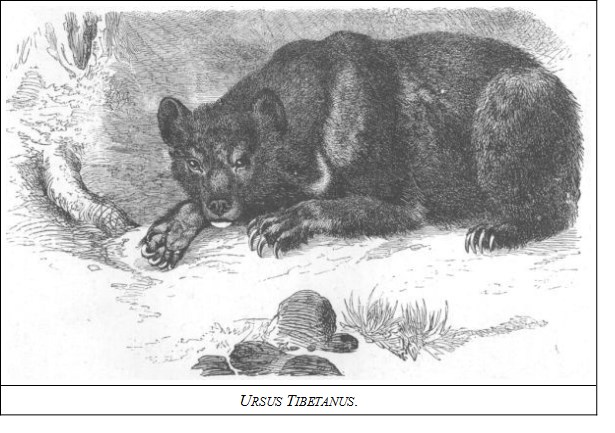

NO. 164. URSUS (HELARCTOS) TORQUATUS vel TIBETANUSThe Himalayan Black Bear (Jerdon's No. 90)NATIVE NAME.—Bhalu, Hind.; Thom, Bhot.; Sona, Lepcha.

HABITAT.—The Himalayas, Nepal, Assam, Eastern Siberia, and China.

DESCRIPTION.—Entirely black, with the exception of a broad white V-shaped mark on the chest and a white chin. Neck thick, head flattened; ears large; claws very long and curved; fur short; body and head more slender than the preceding species.

Jerdon remarks that the specific name of this bear is unfortunate, since it is rare in Thibet. However the more appropriate specific name torquatus is now more generally adopted. It seems to be common in all the Himalayan ranges, where it is to be found from 5000 to 12,000 feet. Jerdon says it lives chiefly on fruit and roots, apricots, walnuts, apples, currants, &c., and also on various grains, barley, Indian corn, buckwheat, &c., and in winter on acorns, climbing the oak trees and breaking down the branches. They are not afraid of venturing near villages, and destroy not only garden stuff, but—being, like all bears, fond of honey—pull down the hives attached to the cottages of the hill people. "Now and then they will kill sheep, goats, &c., and are said occasionally to eat flesh. This bear has bad eyesight, but great power of smell, and if approached from windward is sure to take alarm. A wounded bear will sometimes show fight, but in general it tries to escape. It is said sometimes to coil itself into the form of a ball, and thus roll down steep hills if frightened or wounded." If cornered it attacks savagely, as all bears will, and the face generally suffers, according to Jerdon; but I have noticed this with the common Indian Sloth Bear, several of the men wounded in my district had their scalps torn. He says: "It has been noticed that if caught in a noose or snare, if they cannot break it by force they never have the intelligence to bite the rope in two, but remain till they die or are killed." In captivity this bear, if taken young, is very quiet, but is not so docile as the Malayan species.7

In The Asian of January 7th, 1879, page 68, a correspondent ("N. F. T. T.") writes that he obtained a specimen of this bear which was coal black throughout, with the exception of a dark dirty yellow on the lower lip, but of the usual crescentic white mark she had not a trace. This exceptional specimen was shot in Kumaon. Robinson, in his 'Account of Assam,' states that these bears are numerous there, and in some places accidents caused by them are not unfrequent.

All the Sun Bears are distinguished for their eccentric antics, conspicuous among which is the gift of walking about on their hind legs in a singularly human fashion. Those in the London Zoological Gardens invariably attract a crowd. They struggle together in a playful way, standing on their hind legs to wrestle. They fall and roll, and bite and hug most absurdly.

Captain J. H. Baldwin, in his 'Large and Small Game of Bengal,' puts this bear down as not only carnivorous, but a foul feeder. He says: "On my first visit to the hills I very soon learnt that this bear was a flesh-eater, so far as regards a sheep, goats, &c., but I could hardly believe that he would make a repast on such abominations (i.e. carrion), though the paharies repeatedly informed me that such was the case. One day, however, I saw a bear busy making a meal off a bullock that had died of disease, and had been thrown into the bed of a stream." In another page Captain Baldwin states that the Himalayan Bear is a good swimmer; he noticed one crossing the River Pindur in the flood, when, as he remarks, "no human being, however strong a swimmer, could have stemmed such a roaring rapid."

NO. 165. URSUS (HELARCTOS) GEDROSIANUSBaluchistan BearNATIVE NAME.—Mamh.

HABITAT.—Baluchistan.

DESCRIPTION.—Fur ranging from brown to brownish-black, otherwise as in last species.

This is a new species, brought to notice by Mr. W. T. Blanford, and named by him. The skull of the first specimen procured was scarcely distinguishable from that of a female of Ursus torquatus, and he was for a time apparently in doubt as to the distinctness of the species, taking the brown skin as merely a variety; but a subsequently received skull of an adult male seems to prove that it is a much smaller animal.

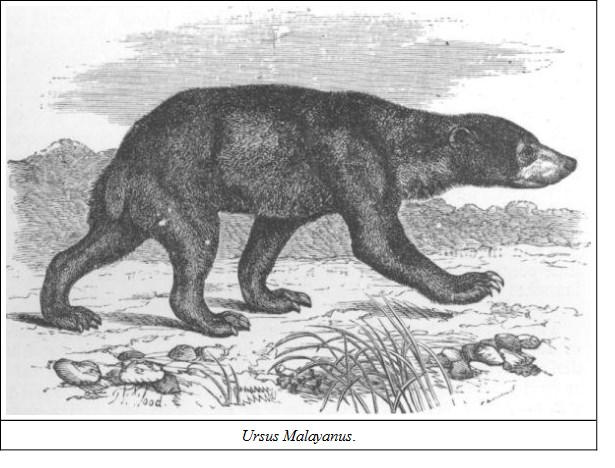

NO. 166. URSUS (HELARCTOS) MALAYANUSThe Bruang or Malayan Sun BearNATIVE NAME.—Wet-woon, Arracan.

HABITAT.—Burmah, Malay Peninsula and adjacent islands.

DESCRIPTION.—Smaller than U. torquatus, not exceeding four and a half feet in length. Fur black, brownish on the nose; the chest marked with a white crescent, or, in the Bornean variety, an orange-coloured heart-shaped patch; the claws are remarkably long; mouth and lower jaw dirty white; the lower part of the crescent prolonged in a narrow white streak down to the belly, where it is widened out into a large irregular spot. Marsden, in his 'History of Sumatra,' published towards the end of the last century, speaks of this bear under the name of Bruang (query: is our Bruin derived from this?), and mentions its habit of climbing the cocoa-nut trees to devour the tender part, or cabbage.

It is more tamable and docile than the Himalayan Sun Bear, and is even more eccentric in its ways. The one in the London "Zoo," when given a biscuit, lies down on its back, and passes it about from fore to hind paws, eyeing it affectionately, and making most comical noises as it rolls about. Sir Stamford Raffles writes of one which was in his possession for two years:—"He was brought up in the nursery with the children; and when admitted to my table, as was frequently the case, gave a proof of his taste by refusing to eat any fruit but mangosteens, or to drink any wine but champagne. The only time I ever knew him out of humour was on an occasion when no champagne was forthcoming. He was naturally of a playful and affectionate disposition, and it was never found necessary to chain or chastise him. It was usual for this bear, the cat, the dog, and a small blue mountain bird, or lory, of New Holland, to mess together and eat out of the same dish. His favourite playfellow was the dog, whose teasing and worrying was always borne, and returned with the utmost good humour and playfulness. As he grew up he became a very powerful animal, and in his rambles in the garden he would lay hold of the largest plantains, the stems of which he could scarcely embrace, and tear them up by the roots." The late General A. C. McMaster gives an equally amusing account of his pet of this species which was obtained in Burmah. "Ada," he writes, "is never out of temper, and always ready to play with any one. While she was with me, 'Ada' would not eat meat in any shape; but I was told by one of the ship's officers that another of the same species, 'Ethel' (also presented by me to the Committee of the People's Park of Madras, and by them sent to England), while coming over from Burmah killed and devoured a large fowl put into her cage. I do not doubt the killing, for at that time 'Ethel' had not long been caught, and was a little demon in temper, but I suspect that, while attention was taken off, some knowing lascar secured the body of the chicken, and gave her credit for having swallowed it. 'Ada's' greatest delight was in getting up small trees; even when she was a chubby infant I could, by merely striking the bark, or a branch some feet above her head, cause her to scramble up almost any tree. At this time poor 'Ada,' a Burman otter, and a large white poodle were, like many human beings of different tastes or pursuits, very fast friends." In another part he mentions having heard of a bear of this species who delighted in cherry brandy, "and on one occasion, having been indulged with an entire bottle of this insinuating beverage, got so completely intoxicated that it stole a bottle of blacking, and drank off the contents under the impression that they were some more of its favourite liquor. The owner of the bear told me that he saw it suffering from this strange mixture, and evidently with, as may easily be imagined, a terrible headache."

So much for the amusing side of the picture, now for the other.

Although strictly frugivorous, still it has been known to attack and devour man in cases of the greatest want, and it also occasionally devours small animals and birds, in the pursuit of which, according to Dr. Sal Müller, it prefers those that live on a vegetable diet. The Rev. Mr. Mason, in his writings about Burmah, says "they will occasionally attack man when alone;" he instances a bear upsetting two men on a raft, and he goes on to add that "last year a Karen of my acquaintance in Tonghoo was attacked by one, overcome, and left by the bear for dead." In this case there was no attempt to devour, and it may have been, as I have often observed with the Indian Sloth Bear, that such attacks are made by females with young.

Dr. Sal Müller states: "in his native forests this bear displays much zeal and ingenuity in discovering the nests of bees, and in extracting their contents by means of his teeth from the narrow orifices of the branches of the trees in which they are concealed."

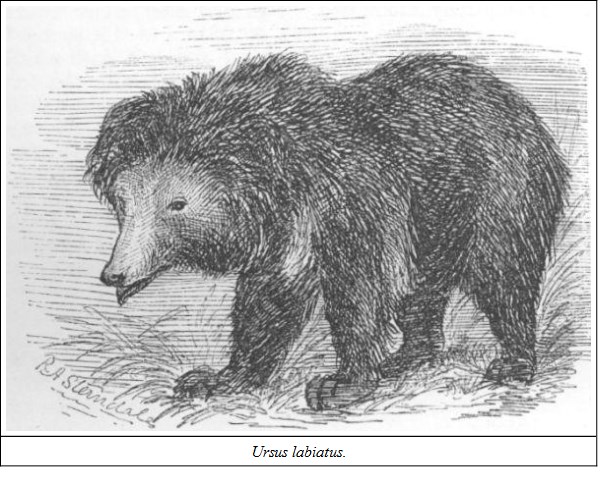

The next species constitutes the genus Melursus of Meyer or Prochilus of Illiger. It is an awkward-shaped beast, from which it probably derives its name of "Sloth Bear," for it is not like the sloth in other respects. It has long shaggy hair, large curved claws (which is certainly another point of resemblance to the sloth), and a very much elongated mobile snout. Another peculiarity is in its dentition; instead of six incisors in the upper jaw it has only four.

Blyth, in his later writings, adopts Illiger's generic name Prochilus.

NO. 167. URSUS (MELURSUS) LABIATUSThe Common Indian Sloth BearNATIVE NAMES.—Bhalu, Hind.; Reench, Hind.; Riksha, Sanscrit; Aswail, Mahr.; Elugu, Tel.; Kaddi or Karadi, Can.; Yerid or Asol of the Gonds; Banna of the Coles.

HABITAT.—All over the peninsula of India. Blyth says it is not found in Burmah.

DESCRIPTION.—General shape of the ursine type, but more than usually ungainly and awkward. Hair very long and shaggy, all black, with the exception of a white V-shaped mark on the chest, and dirty whitish muzzle and tips to its feet; snout prolonged and flexible; claws very large.

SIZE.—A large animal of this species will measure from five to six feet in length, and stand nearly three feet high, weighing from fifteen to twenty stones.

Our old friend is so well known that he hardly requires description, and the very thought of him brings back many a ludicrous and exciting scene of one's jungle days. There is frequently an element of comicality in most bear-hunts, as well as a considerable spice of danger; for, though some people may pooh-pooh this, I know that a she-bear with cubs is no despicable antagonist. Otherwise the male is more anxious to get away than to provoke an attack.

This bear does not hibernate at all, but is active all the year round. In the hot weather it lies all day in cool caves, emerging only at night. In March and April, when the mohwa-tree is in flower, it revels in the luscious petals that fall from the trees, even ascending the branches to shake down the coveted blossoms. The mohwa (Bassia latifolia) well merits a slight digression from our subject. It is a large-sized umbrageous tree, with oblong leaves from four to eight inches long, and two to four inches broad. The flowers are globular, cream coloured, with a faint greenish tint, waxy in appearance, succulent and extremely sweet, but to my taste extremely nasty, there being a peculiar disagreeable flavour which lingers long in the mouth. However not only do all animals, carnivorous as well as herbivorous, like them, but they are highly appreciated by the natives, who not only eat them raw, but dry them in the sun and thus keep them for future consumption, and also distil an extremely intoxicating spirit from them. The fresh refuse, or marc, after the extraction of the spirit is also attractive to animals. Some years ago I sent to Mr. Frank Buckland, for publication in Land and Water, an account of a dog which used to frequent a distillery for the purpose of indulging in this refuse, the result of which was his becoming completely intoxicated. This marc, after further fermentation, becomes intensely acid, and on one occasion I used it successfully in cleaning and brightening a massive steel and iron gate which I had constructed. I made a large vat, and filling it with this fermented refuse, put the gate in to pickle. The seeds of the mohwa yield an oil much prized by the natives, and used occasionally for adulterating ghee. The wood is not much used; it is not of sufficient value to compensate for the flower and fruit, consequently the tree is seldom cut down. When an old one falls the trunk and large limbs are sometimes used for sluices in tanks, for the heart wood is generally rotten and hollow, and it stands well under water. If you ask a Gond about the mohwa he will tell you it is his father and mother. His fleshly father and mother die and disappear, but the mohwa is with him for ever! A good mohwa crop is therefore always anxiously looked for, and the possession of trees coveted; in fact a large number of these trees is an important item for consideration in the assessment of land revenues. No wonder then that the villager looks with disfavour on the prowling bear who nightly gathers up the fallen harvest, or who shakes down the long-prayed-for crop from the laden boughs.

The Sloth Bear is also partial to mangos, sugar-cane, and the pods of the amaltas or cassia(Cathartocarpus fistula), and the fruit of the jack-tree (Artocarpus integrifolia).

It is extremely fond of honey, and never passes an ant-hill without digging up its contents, especially those of white ants. About twenty years ago my first experience of this was in a neighbour's garden. He had recently built himself a house, and was laying out and sowing his flower-beds with great care. It so happened that one of the beds lay over a large ants' nest, and to his dismay he found one morning a huge pit dug in the centre of it, to the total destruction of all his tender annuals, by a bear that had wandered through the station during the night. Tickell describes the operation thus: "On arriving at an ant-hill the bear scrapes away with the fore-feet till he reaches the large combs at the bottom of the galleries. He then with violent puffs dissipates the dust and crumbled particles of the nest, and sucks out the inhabitants of the comb by such forcible inhalations as to be heard at two hundred yards distant or more. Large larvæ are in this way sucked out from great depths under the soil."

Insects of all sorts seem not to come amiss to this animal, which systematically hunts for them, turning over stones in the operation.

The Sloth Bear has usually two young ones at a birth. They are born blind, and continue so till about the end of the third week. The mother is a most affectionate parent, defending her offspring with the greatest ferocity. A she-bear with cubs is always an awkward customer, and she continues her solicitude for them till they are nearly full grown. The young ones are not difficult to rear if ordinary care be taken. The great mistake that most people make in feeding the young of wild animals is the giving of pure cows' milk. I mentioned this in 'Seonee' in speaking of a bear:—

"The little brute was as savage as his elders, and would do nothing but walk to the end of the string by which he was attached to a tent peg, roll head over heels, and walk in a contrary direction, when a similar somersault would be performed; and he whined and wailed just like a child; one might have mistaken it for the puling of some villager's brat. Milford was going to give it pure cows' milk when Fordham advised him not to do so, but to mix it with one half the quantity of water. 'The great mistake people make,' he said, 'who try to rear wild animals, is to give them what they think is best for them, viz., good fresh cows' milk, and they wonder that the little creatures pine away and die, instead of flourishing on it. Cows' milk is too rich; buffalos' milk is better, but both should be mixed with water. It does not matter what the animal is: tiger-cub, fawn, or baby monkey—all require the same caution.'"

I had considerable experience in the bringing up of young things of all sorts when in the Seonee district, and only after some time learnt the proper proportions of milk and water, and also that regularity in feeding was necessary—two-thirds water to one of milk for the first month; after that half and half.

The Sloth Bear carries her cubs on her back, as do the opossums, and a singular little animal called the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus)—and she seems to do this for some time, as Mr. Sanderson writes he shot one which was carrying a cub as large as a sheep-dog.

In that most charming of all sporting books ever written, Campbell's 'Old Forest Ranger,' there is an amusingly-told bit with reference to this habit of cub-carrying which I am sure my readers will forgive me for extracting. Old Dr. Jock M'Phee had been knocked over by a she-bear, and is relating his grievances to Charles:—

"Well, as I was saying, I was sitting at my pass, and thinking o' my old sweethearts, and the like o' that, when a' at ance I heard a terrible stramash among the bushes, and then a wild growl, just at my very lug. Up I jumps wi' the fusee in my hand, and my heart in my mouth, and out came a muckle brute o' a bear, wi' that wee towsie tyke sitting on her back, as conciety as you please, and haudin' the grip like grim death wi' his claws. The auld bear, as soon as she seed me, she up wi' her birse, and shows her muckle white teeth, and grins at me like a perfect cannibal; and the wee deevil he sets up his birse too, and snaps his bit teeth, and tries to grin like the mither o't, with a queer auld farrant look that amaist gart me laugh; although, to tell the blessed truth, Maister Charles, I thought it nae laughing sport. Well, there was naething else for it, so I lets drive at them wi' the grit-shot, thinking to ding them baith at ance. I killed the sma' ane dead enough; but the auld one, she lets a roar that amaist deeved me, and at me she comes like a tiger. I was that frighted, sir, I did na ken what to do; but in despair I just held out the muzzle o' the fusee to fend her off, and I believe that saved my life, for she gripped it atween her teeth, dang me o'er the braid o' my back, and off she set, trailing me through the bushes like a tether-stick; for some way or other I never let go the grip I had o' the stock. I was that stupefied I hae nae recollection what happened after this, till I found mysel' sticking in the middle o' a brier-bush, wi' my breeks rived the way you see, and poor old 'Meg' smashed in bits—de'el be in her skin that did it."