полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

Poor old Jock M'Phee! On the whole he did well to escape with but injury to his garments. I have seen several men mauled by she-bears; one of them was scalped and torn to such an extent that it was a long time before he recovered; and I always marvelled to think he got over it at all.

The British soldier is rather fond of a bear cub as a pet; and Captain Baldwin tells an amusing story of one which followed the men on to the parade ground, and quite disorganised the manoeuvres by frightening the colonel's horse. In 1858 I was quartered for a time with a naval brigade; and once, when there was an alarm of the enemy, Jack went to the front with all his pets, including Bruin, which brought up the rear, shuffling along in blissful ignorance of the bubble reputation to be found at the cannon's mouth.

Although as a rule vegetarian, yet this species is not altogether free from the imputation of being a devourer of flesh when it comes in its way. In such cases it possibly has been impelled by hunger, and I doubt whether it ever kills for the sake of eating. I have known even ruminants eat meat, and in their case hunger could not have been urged as an excuse. Mr. Sanderson mentions an instance when a Barking Deer he shot was partially devoured by a bear during the night.

Very few elephants, however steady with tigers, will stand a bear. Whether it is that bears make such a row when wounded, or whether there be anything in the smell, I know not, but I have heard many sportsmen allude to the fact. A favourite elephant I had would stand anything but a bear and a pig. Few horses will approach a bear, and this is one difficulty in spearing them; and for this reason I think bear dancers should be prohibited in towns. Calcutta used to swarm with them at one time. It always makes me angry when I see these men going about with the poor brutes, whose teeth and claws are often drawn, and a cruel ring passed through their sensitive nostrils. I should like to set an old she-bear after the bhalu-wallas, with a fair field and no favour.

The bear rising to hug its adversary is a fallacy as far as this species is concerned; it does not squeeze, but uses its claws freely and with great effect.

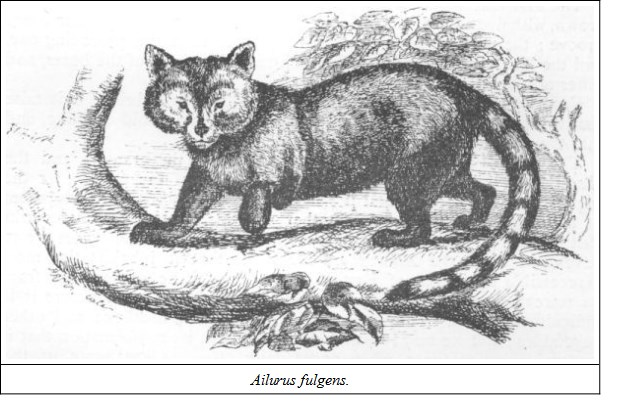

I think we have now exhausted our Indian bears. Some have spoken of a dwarf bear supposed to inhabit the Lower Himalayas, but as yet it is unknown—possibly it may be the Ailuropus. We now come to the Bear-like animals, the next in order, being the Racoons (Procyon), Coatis (Nasua), Kinkajous (Cercoleptes), and the Cacomixle (Bassaris) of North and South America, and then our own Panda or Cat-Bear (Ailurus fulgens).

This, with the above-mentioned Racoons, &c., forms a small group of curious bear-like animals, mostly of small size. Externally they differ considerably, especially in their long bushy tails, but in all essential particulars they coincide. They are plantigrade, and are without a cæcum or blind gut; the skull, however it may approach to a viverrine or feline shape, has still marked arctoid characteristics. The ear passage is well marked and bony, as in that of the bear, but the bulb of the drum (bulla tympani) is much developed, as in the dogs and cats. The molars are more tuberculated than in the bears, resembling the hinder molars of a dog.

AILURIDÆF. Cuvier, who received the first specimen of the type of this family from his son-in-law, M. Duvaucel, was not happy in his selection of a name, which would lead one to suppose that it was affixed to the cats instead of the bears. It certainly in some degree resembles the cat externally, and it has also semi-retractile claws, but in greater measure it belongs to the Arctoidea. There are only two genera as yet known—the Red Cat-Bear, Ailurus fulgens, and the Thibetan Ailuropus melanoleucos.

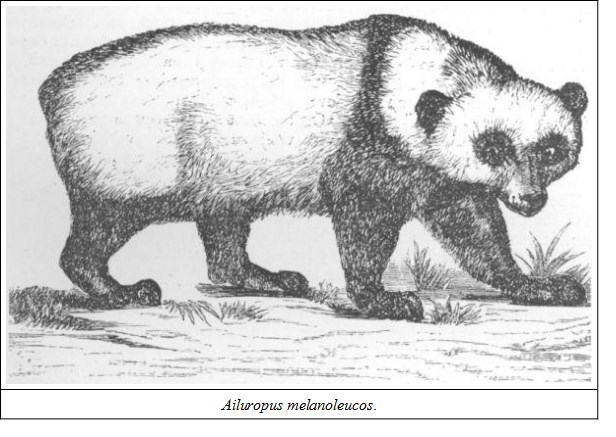

GENUS AILUROPUSThis very rare and most curious animal should properly come between the bears and Ailurus, as it seems to form a link between the two. Such also is the idea of a naturalist friend of mine, who, in writing to me about it, expressed it as being a link between Helarctos Malayanus and Ailurus fulgens. Very little is, however, known of the creature, which inhabits the most inaccessible portions of a little-known country—the province of Moupin in Eastern Thibet. It was procured there by the Abbé David, who, after a prolonged residence in China, lived for nearly a year in Moupin, and he sent specimens of the skull, skin, &c., to M. Alphonse Milne-Edwards, from whose elaborate description in his 'Recherches sur les Mammifères' I have extracted the following notice. The original article is too long to translate in extenso, but I have taken the chief points.

NO. 168. AILUROPUS MELANOLEUCOSHABITAT.—The hilly parts Moupin, Eastern Thibet.

DESCRIPTION.—The Ailuropus has a thick-set heavy form. His head is short, rather slender in front, but extremely enlarged in the middle and after part; the nose is small and naked at its extremity; the forehead very large and convex; the eyes are small; the ears short, wide between and rounded at the ends; neck thick and very strong; the body is squat and massive; the tail is so short as to be hardly distinguishable. The feet are short, very large, nearly of the same length, terminated by five toes very large and with rounded ends, the general conformation of which recalls in all respects those of the bears, but of which the lower parts, instead of being completely placed on the sole in walking and entirely naked or devoid of hair, are always in great measure raised, and abundantly clad with fur to almost their full extent.

On the hind feet can be noticed at the base of the toes a transverse range of five little fleshy pads, and towards the anterior extremity of the metatarsal region another naked cushion placed transversely; but between these parts, as well as the posterior two-thirds of the planta, the hair is as abundant and as long almost as on the upper part of the foot. In the fore-limbs the disposition is much the same, though the metacarpal cushion may be larger; and there is another fleshy pad without hair near the claws.

The Ailuropus is thus an animal not strictly plantigrade, like the Bears in general, or the same as the Polar Bear, of which the feet, although placed flat on the earth, are not devoid of hair; but, on the contrary, the Ailuropus resembles the Ailurus, which is semi-plantigrade, yet hairy under Its soles.

The colouring of the Ailuropus is remarkable: it is white with the exception of the circumferences of the eyes, the ears, the shoulders, and the lower part of the neck which are entirely black. These stand out clearly on a groundwork of slightly yellowish-white; the spots round the eyes are circular, and give a strange aspect to the animal; those on the shoulders represent a sort of band placed transversely across the withers, widening as they descend downwards to lower limbs. The hinder limbs are also black from the lower part of the thigh down to the toes, but the haunches, as also the greater part of the tail, are as white as the back and belly; the colouring is the same in young and old. The fur is long, thick, and coarse, like that of the bears.

From the general form of the skull it would seem impossible to determine the family to which this animal belongs. In effect the head differs considerably from the Ursidæ and the Mustelidæ, and presents certain resemblances to that of the hyæna; but there are numerous and important particulars which indicate a special zoological type, and it is only by an inspection of the dental system that the natural affinities of the Ailuropus can be determined.

In the upper jaw the incisors are, as usual, in three pairs. They are remarkable for their oblique direction; the centre ones are small and a little widened at the base; the second pair are stronger and dilated towards the cutting edge; the external incisors are also strong and excavated outside to admit the canines of the lower jaw. The canines are stout, but short, with a well-marked blunt ridge down the posterior side, as in the Malayan bears.

The molars are six in number on each side, of which four are premolars, and two true molars. The first premolar, situated behind, a little within the line of the canine, is very small, tuberculiform, and a little compressed laterally. The second is strong and essentially carnassial; it is compressed laterally and obliquely placed. It is furnished with three lobes: the first lobe is short, thick, and obtuse; the second is raised, triangular and with cutting edges; the third of the size of the first, but more compressed—in short, a double-fanged tooth. This molar differs considerably from the corresponding tooth of the bear by its form and relative development, since in that family it is one-fanged, very low and obtuse. On the contrary, it approaches to that of the hyænas and felines. With the panda (Ailurus fulgens) the corresponding premolar is equally large, double-fanged and trenchant, but the division in lobes is not so marked.

The third or penultimate molar of the Ailuropus is larger and thicker than the preceding, divided in five distinct lobes—three outer ones in a line, and two less projecting ones within.

The last premolar is remarkably large; it is much larger behind than in front, and its crown is divided into six lobes, of which five are very strong; the three external ones are much developed and trenchant, the centre one being the highest and of a triangular shape. Of the internal lobes, the first one is almost as large as the external ones; the second is very small, almost hidden in the groove between the last mentioned; and the third, which is very large, rounded and placed obliquely inwards in front, and outwards behind. Professor Milne-Edwards remarks that he knows not amongst the carnivora a similar example of a tooth so disposed. That of Ailurus shows the least difference, that is to say it is nearest in structure, having also six lobes, but more thick-set or depressed.

The true molars are remarkable for their enormous development: the first is almost square, with blunt rounded cusps, four-fanged, and presenting a strange mixture of characteristics, in its outward portion resembling an essentially carnivorous type, and its internal portion that of molars intended to triturate vegetable substances. Amongst bears, and especially the Malayan bears, this character is presented, but in a less striking degree; the panda resembles it more, with certain restrictions, but the most striking analogy is with the genus Hyænarctos.

The last molar is peculiar in shape, longer than broad, and is tuberculous, as in the bears, but it differs in this respect from the pandas, in which the last molar is almost a repetition of the preceding one, and its longitudinal diameter is less than its transverse.

In the lower jaw the first premolar, instead of being small and tuberculate, as its corresponding tooth in the upper jaw, is large, double-fanged, trenchant and tri-lobed, resembling, except for size, the two following ones. The second is not inserted obliquely like its correspondent in the upper jaw, its axis is in a line with that of its neighbours; tricuspidate, the middle lobe being the highest. The third premolar is very large, and agrees with its upper one, excepting the lobule on the inner border.

The first true molar is longer than broad, and wider in front; the crown, with five conical tubercles in two groups, separated by a transverse groove; the next molar is thicker and stouter than the preceding one, and the last is smaller, and both much resemble those of the bears, and differ notably from the pandas.

From what M. Milne-Edwards describes, we may briefly epitomise that the premolarial dentition of the Ailuropus is ailuroid or feline, and that the true molars are arctoid or ursine.

The skull is remarkable for the elongation of the cranium and the elevation of the occipital crest, for the shortness of the muzzle, for the depression of the post-frontal portion, and for the enormous development of the zygomatic arches. In another part M. Milne-Edwards remarks that there is no carnivorous animal of which the zygomatic arches are so developed as in the Ailuropus. He states that it inhabits the most inaccessible mountains of Eastern Thibet, and it never descends from its retreats to ravage the fields, as do the Black Bears; therefore it is difficult to obtain. It lives principally on roots, bamboos and other vegetables; but we may reasonably suppose from its conformation that it is carnivorous at times, when opportunity offers, as are some of the bears, and as is the Ailurus. I have dwelt at some length on this animal, though not a denizen of India proper; but it will be a prize to any of our border sportsmen who come across it on the confines of Thibet, and therefore I have deemed it worthy of space.

SIZE.—From muzzle to tail, about four feet ten inches; height about twenty-six inches.

GENUS AILURUSNO. 169. AILURUS FULGENSThe Red Cat-Bear (Jerdon's No. 92)NATIVE NAMES.—Wah, Nepal; Wah-donka, Bhot.; Sunnam or Suknam, Lepch.; Negalya, Ponya of the Nepalese (Jerdon). In the Zoological Gardens in London it is called the Panda, but I am unable just now to state the derivation of this name.

HABITAT.—Eastern Himalayas and Eastern Thibet.

DESCRIPTION.—"Skull ovate; forehead arched; nose short; brain case ovate, ventricose; the zygomatic arches very large, expanded; crown bent down behind" (Gray). The lower jaw is very massive, and the ascending ramus unusually large, extending far above the zygomatic arch, forming almost a right angle with equal arms. Hodgson's description is: "Ursine arm; feline paw; profoundly cross-hinged, yet grinding jaw, and purely triturative and almost ruminant molar of Ailurus; tongue smooth; pupil round; feet enveloped in woolly socks with leporine completeness. It walks like the marten; climbs and fights with all the four legs at once, like the Paradoxuri, and does not employ its forefeet—like the racoon, coatis, or bears—in eating."

Jerdon's outward description is: "Above deep ochreous-red; head and tail paler and somewhat fulvous, displayed on the tail in rings; face, chin, and ears within white; ears externally, all the lower surface and the entire limbs and tip of tail jet-black; from the eye to the gape a broad vertical line of ochreous-red blending with the dark lower surface; moustache white; muzzle black."

The one at present in the London "Zoo" is thus described: "Rich red-chestnut in colour on the upper surface, jet black as to the lower surface, the limbs also black, the snout and inside of ears white; the tail bushy, reddish-brown in colour and indistinctly ringed."

SIZE.—Head and body 22 inches; tail 16; height about 9; weight about 8 lbs.

Jerdon has epitomised Hodgson's description of the habits of this animal as follows: "The Wah is a vegetivorous climber, breeding and feeding chiefly on the ground, and having its retreat in holes and clefts of rock. It eats fruits, roots, sprouts of bamboo, acorns, &c.; also, it is said, eggs and young birds; also milk and ghee, which it is said to purloin occasionally from the villages. They feed morning and evening, and sleep much in the day. They are excellent climbers, but on the ground move rather awkwardly and slowly. Their senses all appear somewhat blunt, and they are easily captured. In captivity they are placid and inoffensive, docile and silent, and shortly after being taken may be suffered to go abroad. They prefer rice and milk to all other food, refusing animal food, and they are free from all offensive odour. They drink by lapping with the tongue, spit like cats when angered, and now and then utter a short deep grunt like a young bear. The female brings forth two young in spring. They usually sleep on the side, and rolled into a ball, the head concealed by the bushy tail." (For the full account see 'Jour. As. Soc. Beng.' vol. xvi. p. 1113.)

Mr. Bartlett, who has studied the habits of the specimen in the London Gardens, says that in drinking it sucks up the fluids like a bear instead of licking it up like a dog or cat, which disagrees with what Hodgson states above. "When offended it would rush at Mr. Bartlett, and strike at him with both feet, the body being raised like a bear's, and the claws projecting."

General Hardwicke was the first to discover this animal, which he described in a paper read before the Linnæan Society on the 6th of November 1821, but it was not published for some years, and in the meanwhile M. Duvaucel sent one to M. F. Cuvier, who introduced it first to the world. Some years ago I had a beautiful skin of one offered to me for sale at Darjeeling by some Bhotias, but as it was redolent of musk and other abominations quite foreign to its innocent inodorous self, I declined to give the high price wanted for it.

SEMI-PLANTIGRADESThese form part of the Plantigrada of Cuvier and part of the Digitigrada; they walk on their toes, but at the same time keep the wrist and heel much nearer to the ground than do the true Digitigrades, and sometimes rest on them. Of those Semi-plantigrades with which we now have to deal there are three sections, viz., the Mustelidæ, containing the Gluttons, Martens, Weasels, Ferrets, Grisons, &c., the Melidæ, Melididæ and Melinidæ of various authors: i.e. Badgers, Ratels, and Skunks; and the Lutridæ or Otters. Some writers bring them all under one great family, Mustelidæ, but the above tripartite arrangement is, I think, better for ordinary purposes. To the mind of only moderate scientific attainments, a distinct classification of well-defined groups is always an easier matter than a large family split up into many genera defined by internal anatomical peculiarities.

Of the Semi-plantigrades at large Jerdon remarks: "None of them have more than one true molar above and another below, which, however, vary much in development, and the flesh tooth is most marked in those in which the tuberculate is least developed, and vice versa. The great and small intestines differ little in calibre, and many of them (i.e. the family) can diffuse at will a disgusting stench." This last peculiarity is a specialty of the American members of the family, notably the skunk, of the power of which almost incredible stories are told. I remember reading not long ago an account of a train passing over a skunk, and for a time the majority of the passengers suffered from nausea in consequence. Sir John Richardson writes: "I have known a dead skunk thrown over the stockades of a trading port produce instant nausea in several women in a house with closed doors, upwards of a hundred yards distant." The secretion is intensely inflammatory if squirted in the eye.

MELIDIDÆ; OR, BADGER-LIKE ANIMALSThis group is distinguished by a heavier form, stouter limbs, coarse hair, and slower action; in most the claws are adapted for burrowing. None of them are arboreal, although in olden times marvellous tales were told of the wolverene or glutton as being in the habit of dropping down from branches of trees on the backs of large animals, clinging on to them and draining their life blood as they fled. Some of them are capable of emitting a noisome smell. The teledu of Java (Mydaus meliceps) is the worst of the family in this respect, and almost equals the skunk. It is possible that this animal may be found in Tenasserim.

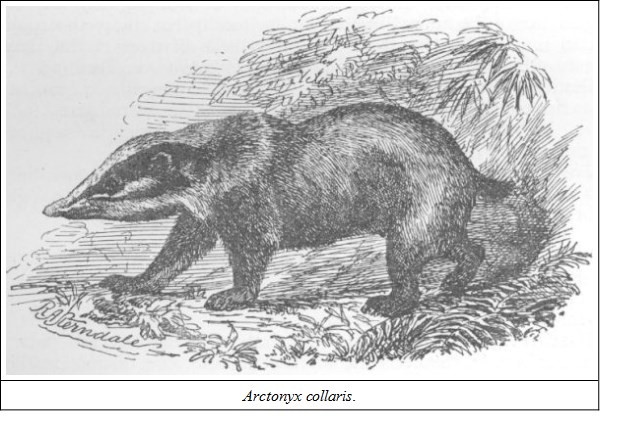

GENUS ARCTONYXDentition much the same as that of the Badger (Meles). Incisors, 6/6; can., 1—1/1—1; premolars, 3—3/3—3; molars, 1—1/1—1. The incisors are disposed in a regular curve, vertical in the upper jaw, obliquely inclined in the lower; canines strong, grinders compressed; general form of the badger, but stouter. Feet five-toed, with strong claws adapted for digging, that of the index finger being larger than the other.

NO. 170. ARCTONYX COLLARISThe Hog-Badger (Jerdon's No. 93)NATIVE NAMES.—Balu-suar, Hind., Sand-pig, or, as Jerdon has it, Bhalu-soor, Hind., i.e. Bear-pig; Khway-too-wet-too, Arakanese.

HABITAT.—Nepal, Sikim, Assam, Sylhet, Arakan, extending, as Dr. Anderson has observed, to Western Yunnan. The late General A. C. McMaster found it in Shway Gheen On the Sitang river in Pegu. I heard of it in the forests of Seonee in the Central Provinces, but I never came across one.

DESCRIPTION.—"Hair of the body rough, bristly, and straggling; that of the head shorter, and more closely adpressed. Head, throat, and breast yellowish white; on the upper part this colour forms a broad regularly-defined band from the snout to the occiput; ears of the same colour; the nape of the neck, a narrow band across the breast, the anterior portion of the abdomen, the extremities, a band arising from the middle of the upper lip, gradually wider posteriorly, including the eyes and ears, and another somewhat narrower arising from the lower lip, passing the cheek, uniting with the former on the neck, are deep blackish-brown" (Horsfield). The tail is short, attenuated towards the end, and covered with rough hairs.

SIZE.—From snout to root of tail, 25 inches; tail, 7 inches; height at the rump, 12 inches.

M. Duvaucel states that "it passes the greatest part of the day in profound somnolence, but becomes active at the approach of night; its gait is heavy, slow, and painful; it readily supports itself erect on its hind feet, and prefers vegetables to flesh."

Jerdon alludes to all this, and adds, "one kept in captivity preferred fruit, plantains, &c., as food, and refused all kinds of meat. Another would eat meat, fish, and used to burrow and grope under the walls of the bungalow for worms and shells." My idea is Balu-suar, or Sand-pig is the correct name, although Bhalu-suar or Bear-pig may hit off the appearance of the animal better, but its locality has always been pointed out to me by the Gonds in the sandy beds of rivers in the bamboo forests of Seonee; and Horsfield also has it Baloo-soor, Sand-pig.

Bewick, who was the first to figure and describe it, got, as the vulgar phrase hath it, the wrong pig by the lug, as he translates it Sand-bear. McMaster also speaks of those he saw as being in deep ravines on the Sitang river.

The stomach of Arctonyx is simple; there is no cæcum, as is the case also with the bears; the liver has five lobes; under the tail it has glands, as in the Badgers, secreting a fatty and odorous substance.

NO. 171. ARCTONYX TAXOIDESThe Assam BadgerHABITAT.—Assam and Burmah.

DESCRIPTION.—Smaller than the last, with longer and finer fur, narrower muzzle, smaller ears, shorter tail, and more distinct markings. The measurement of the respective skulls show a great difference. The length of a skull of a female of this species given by Dr. Anderson is 4·75 inches against 6·38 of a female of A. collaris. The breadth across the zygomatic arch is 2·38 against 3·64 of A. collaris. The breadth of the palate between the molars is only 0·81 against 1·07.

GENUS MELESSUB-GENUS TAXIDIAThis sub-genus is that of the American type of Badger, to which Hodgson, who first described the Thibetan T. leucurus, supposed his species to belong; but other recent naturalists, among whom are Drs. Gray and Anderson, prefer to class it as Meles. Hodgson founded his classification on the dentition of his specimen, but Blyth has thrown some doubt on its correctness, believing that the skull obtained by Hodgson with the skin was that of Meles albogularis. Hodgson, however, says: "from the English Badger type of restricted Meles our animal may be at once discriminated without referring to skulls by its inferior size, greater length of tail, and partially-clad planta or foot-sole."

NO. 172. MELES (TAXIDIA) LEUCURUSThe Thibetan White-tailed BadgerNATIVE NAME.—Tampha.

HABITAT.—The plains of Thibet.