полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

This sheep has bred in the Gardens of the Zoological Society in London. (See notes to Oorial in Appendix C.)

NO. 444. OVIS BLANFORDIIBlanford's Wild SheepHABITAT.—Central hills of Khelat.

DESCRIPTION.—The horns of this species are longer and more slender than those of Ovis Vignei, O. cycloceros, or O. Gmelini. Mr. Hume says ('J. A. S. B.' 1877, p. 327): "In all these three species, as far as I can make out, each horn lies in one plane, whereas in the present species the horn twists out in a capital-S fashion. There is, in fact, much the same difference between the horns of the present species and of O. cycloceros, that there is between those of O. Kareleni and O. Hodgsoni. The lower part of the forehead at the nasal suture, and the whole of the frontals, are more raised and convex than in either O. cycloceros or O. Vignei.

"The frontal ridge between the bases of the horns is less developed in O. Blanfordii, and in this latter the posterior convex margin of the bony palate is differently shaped, being more pointed, and not nearly semi-circular as in O. cycloceros."

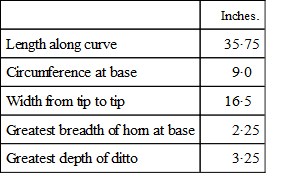

The dimensions of the skull are given in detail by Mr. Hume in the paper above quoted, out of which I extract those of the horns:—

The horns of a specimen of O. cycloceros of about the same age were 29·5 in length and 10 inches in circumference at base, so that the greater length and slenderness of the horns of Ovis Blanfordii are apparent. Mr. Hume writes to me that there is a living specimen of this sheep at present in the London Zoological Gardens.

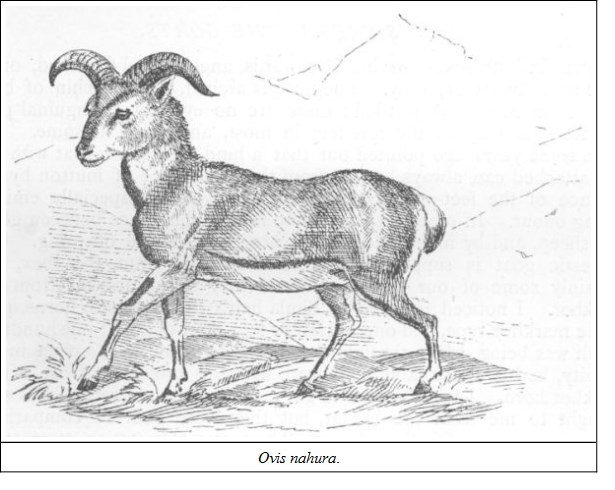

NO. 445. OVIS NAHURA vel BURHELThe Blue Wild Sheep (Jerdon's No. 237)NATIVE NAMES.—Burhel, Buroot, in the Himalayas; Napu, Na, or Sna, Thibet and Ladakh; Nervati, in Nepal. Wa' or War on the Sutlej.

HABITAT.—This animal has a wide range; it is found from Sikim, and, as Jerdon says, probably Bhotan, right away through Thibet, as Père David found it in Moupin, and it extends up to the Kuenluen mountains north of Ladakh, and in Ladakh itself, and it has been obtained by Prejevalski on the Altyn-Tagh, therefore the limits assigned by Jerdon must be considerably extended.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour a dull slaty blue, slightly tinged with fawn; the belly, edge of buttocks, and tail, white; throat, chest, front of fore-arm and cannon bone, a line along the flank dividing the darker tint from the belly; the edge of the hind limbs and the tip of the tail deep black; horns moderately smooth, with few wrinkles, rounded, nearly touching at the base, directed upwards, backwards and outwards, the points being turned forwards and inwards. The female is smaller, the black marks smaller and of less extent; small, straight, slightly recurved horns; nose straighter. The young are darker and browner.

SIZE.—Length of head and body, 4½ to 5 feet; height, 30 to 36 inches; tail, 7 inches; horns, 2 to 2½ feet round the curve; circumference at base, 12 to 13 inches.

An excellent coloured plate is to be found in Blanford's 'Scientific Results of the Second Yarkand Mission' and a life-like photograph of the head in Kinloch's 'Large Game-shooting.' According to the latter author the burrel prefers bare rocky hills, and when inhabiting those which are clothed with forest, rarely or never descends to the limits of the trees. "The favourite resorts of burrel are those hills which have slopes well covered with grass in the immediate vicinity of steep precipices, to which they can at once betake themselves in case of alarm. Females and young ones frequently wander to more rounded and accessible hills, but I have never met with old males very far from some rocky stronghold. The males and females do not appear to separate entirely during the summer, as I have found mixed flocks at all seasons, though, as a rule, the old males form themselves into small herds and live apart. In my opinion the flesh of the burrel surpasses in flavour the best mutton, and has moreover the advantage of being generally tender soon after the animal is killed."

According to Jerdon the burrel is fattest in September and October. In the 'Indian Sporting Review' a writer, "Mountaineer," states that in winter, when they get snowed in, they actually browse the hair off each other, and come out miserably thin.

The name Ovis nahura is not a felicitous one, as it was given under a mistake by Hodgson, the nahoor being quite another animal. I think Blyth's name of Ovis burhel should be adopted to the exclusion of the other, which, however, is in general use.

There is a very interesting paper on this animal by Mr. R. Lydekker in the 'Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal,' vol. xlix., 1880, in which he points out its affinity to the goats from the absence of eye-pits and their larminal depression in the lachrymal bone—from the similarity of the basi-occipital and in the structure and colour of its horns. On the other hand it agrees with Ovis in the form of its lower jaw, in the absence of beard and any odour, and in the possession of interdigital pores in all feet.

GENUS CAPRA—THE GOATSHorns in both sexes curving backwards, angular and flattened, or in some cases twisted spirally. The nose is arched, and the chin of both sexes is more or less bearded; there are no eye-pits or inguinal pits, and feet-pits only in the fore-feet in most, and none in some. Mr. Blyth some years ago pointed out that a hind-quarter of goat with the foot attached can always be told from the same piece of mutton by the absence of the feet-pits in the goat. The males especially emit a strong odour. In other respects there is little difference between goats and sheep, and by interbreeding they produce a fertile offspring. Our domestic goat is supposed to have descended from the ibex, but certainly some of our Indian varieties may claim descent from the markhor. I noticed in 1880 at Simla herds of goats with horns quite of the markhor type, and one old fellow in a herd of about one hundred, which was being driven through the station to some rajah's place in the vicinity, had a remarkably fine head, with the broad flat twist of the markhor horn. I tried in vain to get a similar one; several heads were brought to me from the bazaar, but they were poor in comparison. Goats are more prolific than sheep. The power of gestation commences at the early age of seven months; the period is five months, and the female produces sometimes twice a year, and from two to occasionally four at a birth. The goat is a hardy animal, subsisting on the coarsest herbage, but its flesh and milk can be immensely improved by a selected diet. Some of the small domestic goats of Bengal are wonderful milkers. I have kept them for years in Calcutta for the use of my children, and once took two of them with me to Marseilles by the 'Messageries' Steamers. I prefer them to the larger goats of the North-west. My children have been singularly free from ailments during their infancy, and I attribute the immunity chiefly to the use of goats' milk drawn fresh as required. Of the wild goats, to which I must now confine my attention, there are two groups, viz. the true goats and the antelope goats. Of the former there is a sub-genus—Hemitragus—which have no feet-pits, but have a muffle and occasionally four mammæ, which form a connecting link with the Cervidæ. In all other respects Hemitragus is distinctly caprine.

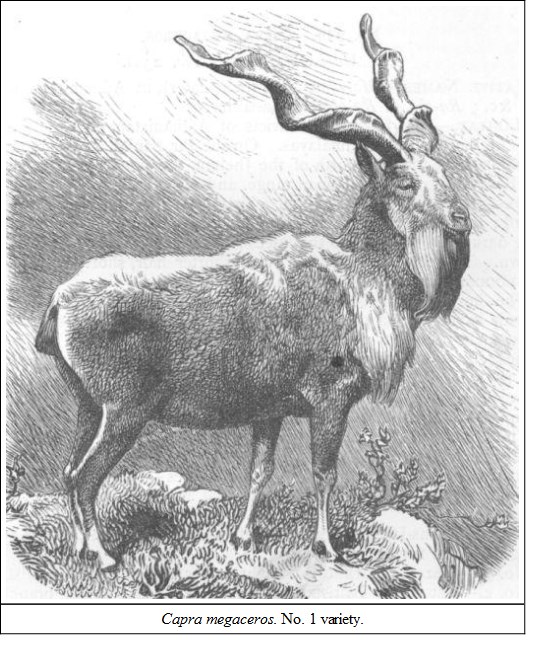

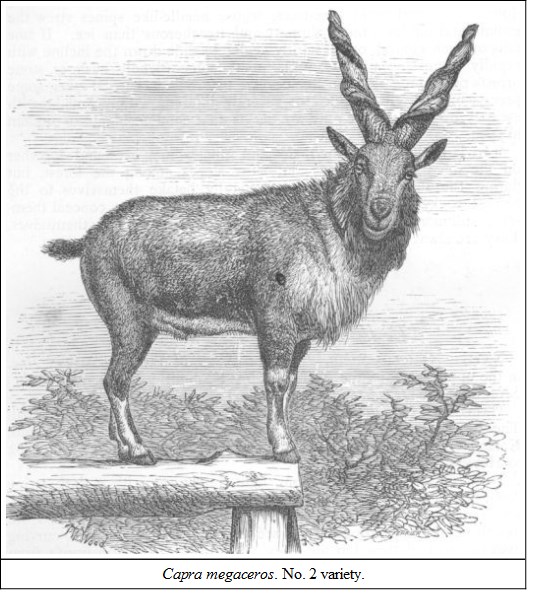

NO. 446. CAPRA MEGACEROSThe Markhor (Jerdon's No. 234)NATIVE NAMES.—Mar-khor (i.e. snake-eater), in Afghanistan, Kashmir, &c.; Rá-che, or Ra-pho-che, Ladakhi.

HABITAT.—The mountain districts of Afghanistan, and the highest parts of the Thibetan Himalayas. On the Pir Panjal, in Kashmir, the Hazarah hills, the hills north of the Jhelum, the Wurdwan hills west of the Beas river, on the Suleiman range, and in Ladakh.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour a dirty light-blue gray, with a darker beard; in summer with a reddish tinge; the neck and breast clad with long dark hair, reaching to the knees; hair long and shaggy; fore-legs brown. The females are redder, with shorter hair, short black beard, but no mane, and with small horns slightly twisted.

The horns of an old male are a magnificent trophy. Kinloch records having seen a pair, of which the unbroken horn measured sixty-three inches, and its fellow, which had got damaged, had fifty-seven inches left. Forty to fifty inches is, however, a fair average. According to Kinloch the very long horns are not so thick and massive as those of average length. Jerdon says the longest horns have three complete spiral twists.

The horns of certain varieties differ so much that I may say species have been settled with less to go upon. Kinloch notes four varieties. I have hitherto reckoned only two, but he gives—

No. 1.—Pir Panjal markhor; heavy, flat horns, twisted like a corkscrew.

No. 2.—Trans-Indus markhor; perfectly straight horns, with a spiral flange or ridge running up them.

No. 3.—Hazarah markhor; a slight corkscrew, as well as a twist.

No. 4.—Astor and Baltistan markhor; large, flat horns, branching out very widely, and then going up nearly straight with only a half turn.

Of the two kinds I have seen, the one has the broad flat horn twisted like a corkscrew; the other a perfectly straight core, with the worm of a screw turned round it. Nothing could be more dissimilar than these horns, yet, in other respects the animal being the same, it has not been considered necessary to separate the two as distinct species.37

SIZE.—Height, about 46 inches.

There is a life-like photograph of No. 1 variety in Kinloch's 'Large Game of Thibet,' and of No. 3 a very fine coloured plate in Wolf's folio of 'Zoological Sketches.'

The markhor frequents steep and rocky ground above the forests in summer, but descending in the winter. I cannot do better than quote Kinloch, who gives the following graphic little description: "The markhor inhabits the most precipitous and difficult ground, where nearly perpendicular faces of rock alternate with steep grassy slopes and patches of forest. It is very shy and secluded in its habits, remaining concealed in the densest thickets during the day-time, and only coming out to feed in the mornings and evenings. No animal's pursuit leads the sportsman over such dangerous ground as that of the markhor. Living so much in the forest, it must be followed over steep inclines of short grass, which the melting snow has left with all the blades flattened downwards; and amid pine-trees, whose needle-like spines strew the ground and render it more slippery and treacherous than ice. If one falls on such ground, one instantly begins to slide down the incline with rapidly increasing velocity, and, unless some friendly bush or stone arrests one's progress, the chances are that one is carried over some precipice, and either killed or severely injured. Many hair-breadth escapes occur, and the only wonder is that fatal accidents so seldom happen.

"Early in the season the males and females may be found together on the open grassy patches and clear slopes among the forest, but during the summer the females generally betake themselves to the highest rocky ridges above the forest, while the males conceal themselves still more constantly in the jungle, very rarely showing themselves. They are always very wary, and require great care in stalking them."

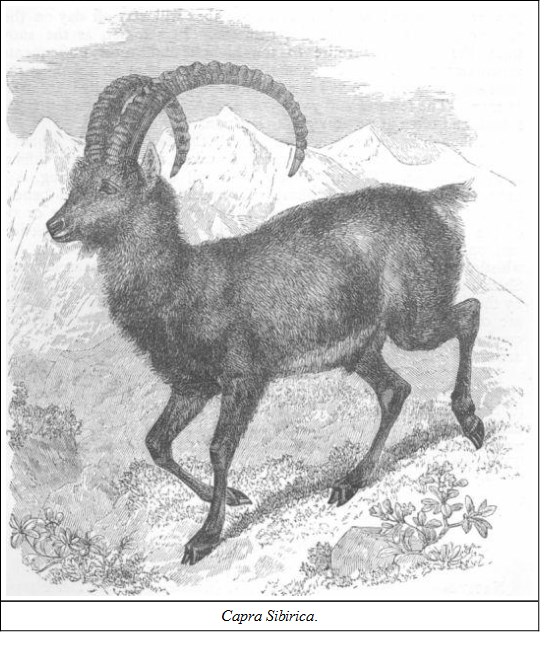

NO. 447. CAPRA SIBIRICAThe Himalayan Ibex (Jerdon's No. 235)NATIVE NAMES.—Sakin, Iskin, or Skeen of the Himalayas; Buz, in the upper part of the Sutlej; Kale, Kashmiri; Tangrol, in Kulu; Skin, the male, L'Damuo the female, in Ladakh.

HABITAT.—Throughout the Himalayas from Kashmir to Nepal. The localities given by Kinloch are Kunawar, Kulu, Lahoul, Spiti, Kashmir, Baltistan, and various parts of Thibet; also Ladakh according to Horsfield.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour light brownish, with a dark stripe down the back in summer, dirty yellowish-white in winter; the beard, which is about six to eight inches long, is black; the horns, which are like those of the European ibex, are long and scimitar-shaped, curving over the neck, flattened at the sides, and strongly ridged in front; from forty to fifty inches in length. A pair is recorded in the 'Proceedings of the Zoological Society' for 1840 of fifty-one inches in length. The females have thin slightly curved horns about a foot long.

Under the hair, which is about two inches long, is a soft down, and is highly prized for the fine soft cloth called tusi.

SIZE.—Height at shoulder, about 44 inches.

According to Colonel Markham the ibex "frequents the highest ground near the snows where food is to be obtained. The sexes live apart generally, often in flocks of one hundred and more. In October the males descend and mix with the females, which have generally twins in June and July. It is an extremely wary and timid animal, and can make its way in an almost miraculous manner over the most inaccessible-looking ground. No animal can exceed the ibex in endurance and agility."

Kinloch writes as follows concerning it:—

"The ibex inhabits the most precipitous ground in the highest parts of the ranges where it is found, keeping above the forest (when there is any), unless driven down by severe weather. In the day-time it generally betakes itself to the most inaccessible crags, where it may sleep and rest in undisturbed security, merely coming down to the grassy feeding grounds in the mornings and evenings. Occasionally, in very remote and secluded places, the ibex will stay all day on their feeding grounds, but this is not common. In summer, as the snows melt, the old males retire to the highest and most unfrequented mountains, and it is then generally useless to hunt for them, as they have such a vast range, and can find food in places perfectly inaccessible to man. The females and young ones may be met with all the year round, and often at no very great elevation.

"Although an excessively wary animal, the ibex is usually found on such broken ground that, if due care be taken, it is not very difficult to obtain a shot. The grand rule, as in all other hill stalking, is to keep well above the herd, whose vigilance is chiefly directed beneath them. In places where they have been much disturbed, one or two of the herd usually keep a sharp look-out while the rest are feeding, and on the slightest suspicion of danger the sentries utter a loud whistle, which is a signal for a general rush to the nearest rocks. Should the sportsman succeed in obtaining a shot before he is observed by the ibex, he may often have time to fire several shots before they are out of range, as they appear to be completely stupefied and confused by the sudden noise, the cause of which they are unable to account for if they neither see nor smell their enemy."

Jerdon states that Major Strutt killed in the Balti valley an ibex of a rich hair-brown colour, with a yellowish-white saddle in the middle of its back, and a dark mesial line; the head, neck and limbs being of a dark sepia brown, with a darker line on the front of the legs; others were seen in the same locality by Major Strutt of a still darker colour. These seem to be peculiar to Balti; the horns are the same as the others. Kinloch remarks that a nearly black male ibex has been shot to the north of Iskardo.

NO. 448. CAPRA ÆGAGRUSThe Wild Goat of Asia MinorNATIVE NAMES.—Pasang (male), Boz (female), generally Boz-Pasang, Persian (Blanford); Kayeek in Asia Minor (Danford).

HABITAT.—Throughout Asia Minor from the Taurus mountains; through Persia into Sindh and Baluchistan; and in Afghanistan. M. Pierre de Tchihatchef, late a distinguished member of the Russian Diplomatic Service, and well known as an author and a man of science, whose acquaintance I had the pleasure of making some time ago in Florence, found these goats most abundant on the Aladagh, Boulgerdagh and Hussandagh ranges of the Taurus. He made a very good collection of horns and skulls there, which are now in the Imperial Museum, St. Petersburg. Captain Hutton found it in Afghanistan.

DESCRIPTION.—Hair short and brown, becoming lighter in summer; a dark, almost black line down the back; the males have a black beard; the young and females are lighter, with fainter markings; the horns are of the usual ibex type, but there is a striking difference between those of this species and all the others. As a rule the ibex horn is triangular in section, that is, the front part of the horn is square, with transverse knobs at short intervals all the way up, for about three-fourths of the length, whereas the horn of C. ægagrus is more scimitar-like, flattish on the inner side and rounded on the outer, with an edge in front; the sides are wavily corrugated, and on the outer edge are knobs at considerable distances apart. It is believed that an estimate of the age of the animal can be made by these protuberances—after the third year a fresh knob is made in each succeeding one. Mr. Danford says: "The yearly growths seem to be greatest from the third to the sixth year, the subsequent additions being successively smaller." The horns sometimes curve inwards and sometimes outwards at the tips. Mr. Danford figures a pair, the tips of which, turning inwards, cross each other. The female horns are shorter and less characteristic. The size of the male horns run to probably a maximum of 50 inches. There is a pair in the British Museum 48½ inches on the curve. Mr. Danford's best specimen was 47½, the chord of which was 22½, basal circumference 9¾, weight 10¼ lbs. Captain Hutton's living specimen had horns 40½ inches in length.

SIZE.—According to Herr Kotschy "it attains not unfrequently a length of 6½ feet." Mr. Danford measured one 5 feet 5½ inches from nose to tip of tail, 2 feet 9½ inches at shoulder. (See also Appendix C.)

I have not had an opportunity of measuring a very well-stuffed specimen in the Indian Museum, but I should say that the Sind variety was much smaller. Standing, as it does, beside a specimen of Capra Sibirica, it looks not much bigger than some of the Jumnapari goats. (See Appendix C.)

The ægagrus is commonly supposed to be the parent stock from which the domestic goat descended, and certainly the European and many Asiatic forms show a similarity of construction in the horn, but the common goat descended from more than one wild stock, for, as I have before stated, there are goats in India, which show unmistakable signs of descent from the markhor, Capra megaceros. In the article on Capra ægagrus in the 'P. Z. S.' for 1875, p. 458, by Mr. C. G. Danford, F.Z.S., written after a recent visit to Asia Minor, it is stated that the late Captain Hutton found it common in Afghanistan, in the Suleiman and Pishin hills, and in the Hazarah and western ranges. I confess I had thought the ibex of these parts to be identical with C. Sibirica. Mr. Danford, describing where he met with it, says:—

"The picturesque town of Adalia is situated at the head of the gulf of the same name, and is the principal place in the once populous district of Pamphylia. It is surrounded on its landward side by a wide brushwood-covered plain, bounded on the north and north-east by the Gok and other mountains of the Taurus, and on the west by the Suleiman, a lofty spur of the same range, in which latter the present specimens were collected.

"These mountains, the principal summit of which, the Akdagh (white mountain), attains a height of 10,000 feet (Hoskyn), rise abruptly from the plain and sea, and are of very imposing and rugged forms. The pure grey tints of the marble and marble-limestone, of which they are principally composed, show beautifully between the snowy summits, and the bright green of the pines and darker shades of the undergrowth of oak, myrtle and bay, which clothe their lower slopes.

"The wild goat is here found either solitary or in small parties and herds, which number sometimes as many as 100; the largest which I saw contained 28. It is called by the natives kayeek, which word, though applied in other parts of the country to the stag, and sometimes even the roe, is here only used to designate the ægagrus, the fallow deer of this district being properly known as jamoorcha. The old males of the ægagrus inhabit during summer the higher mountains, being often met with on the snow, while the females and young frequent the lower and easier ridges; in winter, however, they all seem to live pretty much together among the rocks, scattered pines, and bushy ground, generally preferring elevations of from 2000 to 5000 feet. Herr Kotschy says they never descend below 4000 feet in Cilicia; but his observations were made in summer.

"Like all the ibex tribe, the ægagrus is extremely shy and wary at ordinary times, though, as in the case with many other animals, they may be easily approached during the rutting season. I was told that they were often brought within shot at that time by the hunter secreting himself, and rolling a few small stones down the rocks. When suddenly disturbed they utter a short angry snort, and make off at a canter rather than a gallop. Though their agility among the rocks is marvellous, they do not, according to Mr. Hutton ('Calcutta Journ.' vii. p. 524), possess sufficient speed to enable them to escape from the dogs which are employed to hunt them in the low lands of Afghanistan. It is interesting to see how, when danger is dreaded, the party is always led by the oldest male, who advances with great caution, and carefully surveys the suspected ground before the others are allowed to follow; their food consists principally of mountain grasses, shoots of different small species of oak and cedar, and various berries. The young are dropped in May, and are one or two (Kotschy says sometimes three) in number. The horns appear very early, as shown in a kid of the year procured in the beginning of January."

It appears to be very much troubled with ticks, and an oestrus or bot which deposits its larvæ in the frontal sinuses and cavities of the horns.

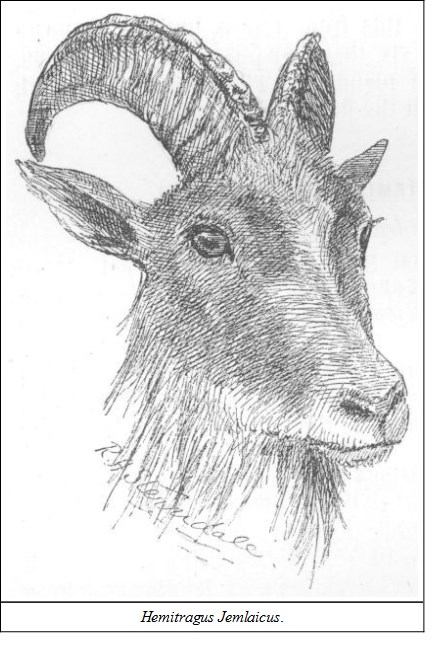

SUB-GENUS HEMITRAGUSSome naturalists do not separate this from Capra, but the majority do on the following characteristics, viz. that they possess a small muffle, and one of the two species has four mammæ. The horns are trigonal, laterally compressed and knotted on the upper edge.

NO. 449. CAPRA vel HEMITRAGUS JEMLAICUSThe Tahr (Jerdon's No. 232)NATIVE NAMES.—Tehr, Jehr, near Simla; Jharal, in Nepal; Kras and Jagla, in Kashmir; Kart, in Kulu; Jhula the male, and Thar or Tharni the female, in Kunawur; Esbu and Esbi, male and female, on the Sutlej above Chini (Jerdon).

HABITAT.—Throughout the entire range of the Himalayas, at high elevations between the forest and snow limits. According to Dr. Leith Adams it is very common on the Pir Panjal, and more so near Kishtwar.

DESCRIPTION.—The male is of various shades of brown, varying in tint from dark to yellowish, the front part and mane being ashy with a bluish tinge, the upper part of the limbs rusty brown, the fronts of legs and belly being darker. There is no beard, the face being smooth and dark ashy, but on the fore-quarters and neck the hair lengthens into a magnificent mane, which sometimes reaches to the knees. There is a dark mesial line; the tail is short and nude underneath; the horns are triangular, the sharp edge being to the front; they are about ten or eleven inches in circumference at the base where they touch, then, sweeping like a demi-crescent backwards, they taper to a fine point in a length of about 12 to 14 inches. The male has at times a very strong odour. The female is smaller, and of a reddish-brown or fulvous drab above, with a dark streak down the back, whitish below; the horns are also much smaller.