полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

In addition to a careful study of De Blainville's 'Ostéographie,' where the bones are figured in large size to scale, I have made many careful measurements of skulls belonging to myself and friends, and also of the skulls and skeletons in the Calcutta Museum (for most willing and valuable assistance in which I am indebted to Mr. J. Cockburn, who, in order to test my calculations, went twice over the ground); and I have adopted the following formula as a tentative measure. I quite expect to be criticised, but if the crude idea can be improved on by others I shall be glad.

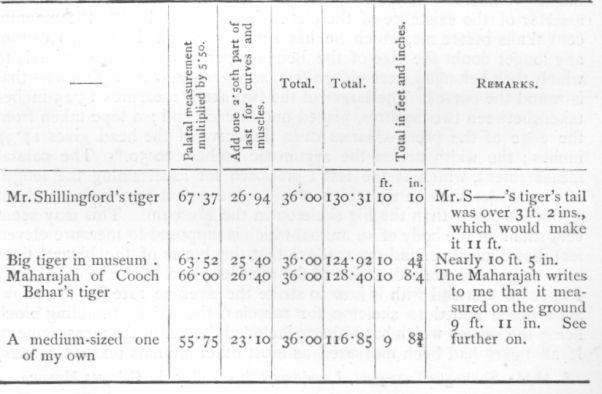

I now give a tabular statement of four out of many calculations made, but I must state that in fixing an arbitrary standard of 36 inches for tail, I have understated the mark, for the tails of most tigers exceed that by an inch or two, though, on the other hand, some are less.

Formula.—Measure from the tip of the premaxillaries or outer insertion of the front teeth (incisors) along the palate to the nearest inner edge of the foramen magnum. Multiply the result by 5·50. This will give the length of the skeleton, excluding the tail. Divide this result by 2·50, and add the quotient to the length for the proportionate amount of muscles and gain in curves. Add 36 inches for tail.

It will be seen that my calculation is considerably out in the Cooch Behar tiger, so I asked the Maharajah to tell me, from the appearance of the skull, whether the animal was young or old. He sent it over to me, and I have no hesitation in saying that it was that of a young tiger, who, in another year, might have put on the extra nine inches; the parietal sutures, which in the old tiger (as in Mr. Shillingford's specimens) are completely obliterated, are in this one almost open. It must be remembered that the bones of the skull do not grow in the same ratio to the others, and that they attain their full size before those of the rest of the body. Therefore it is only in the case of the adult that accurate results can be calculated upon. Probably I have not done wisely in selecting a portion of the skull as a standard—a bone of the body, such as a femur or humerus might be more reliable—but I was driven to it by circumstances. Sportsmen, as a rule, do not keep anything but the skull, and for general purposes it would have been of no use my giving as a test what no one could get hold of except in a museum.

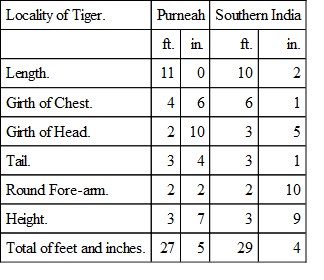

I have always understood that the tiger of the plains grew to a greater size, that is in length, than the tiger of hilly country. I have never shot a tiger in Lower Bengal, therefore I cannot judge of the form of the beast, whether he be more lanky or not. If an eleven-foot Bengal tiger be anything like as robust in proportion as our Central Indian ones, I should say he was an enormous creature, but I believe the Central and Southern tiger to be the heavier one, and this is borne out by an illustration given by Mr. Shillingford in one of his able letters, which have called forth so much hostile criticism. He compares one of his largest with the measurement of a Southern India tiger:—

The shorter tiger has an advantage of nearly two feet in all-round measurement.

Sir Joseph Fayrer has also been called in question for his belief in twelve feet tigers, but what he says is reasonable enough. "The tiger should be measured from the nose along the spine to the tip of the tail, as he lies dead on the spot where he fell, before the skin is removed. One that is ten feet by this measurement is large, and the full-grown male does not often exceed this, though no doubt larger individuals (males) are occasionally seen, and I have been informed by Indian sportsmen of reliability that they have seen and killed tigers over twelve feet in length." ('Royal Tiger of Bengal,' p. 29).

Sir Joseph Fayrer in a letter to Nature, June 27, 1878, brings forward the following evidence of large tigers shot by sportsmen whose names are well known in India.

Lieutenant-Colonel Boileau killed a tiger at Muteara in Oude, in 1861, over 12 feet; the skin when removed measured 13 feet 5 inches.

Sir George Yule has heard once of a 12-foot tiger fairly measured, but 11 feet odd inches is the largest he has killed, and that twice or thrice.

Colonel Ramsay (Commissioner) killed in Kumaon a tiger measuring 12 feet.

Sir Joseph Fayrer has seen and killed tigers over 10 feet, and one in Purneah 10 feet 8 inches, in 1869.

Colonel J. Sleeman does not remember having killed a tiger over 10 feet 6 inches in the skin.

Colonel J. MacDonald has killed one 10 feet 4 inches.

The Honourable R. Drummond, C.S., killed a tiger 11 feet 9 inches, measured before being skinned.

Colonel Shakespeare killed one 11 feet 8 inches.

However, conceding that all this proves that tigers do reach occasionally to eleven and even twelve feet, it does not take away from the fact that the average length is between nine and ten feet, and anything up to eleven feet is rare, and up to twelve feet still more so.11

VARIETIES OF THE TIGER.—It is universally acknowledged that there is but one species of tiger. There are, however, several marked varieties. The distinction between the Central Asian and the Indian tiger is unmistakable. The coat of the Indian animal is of smooth, short hair; that of the Northern one of a deep furry pelage, of a much richer appearance.

There is an idea which is also to be found stated as a fact in some works on natural history, that the Northern tiger is of a pale colour with few stripes, which arises from Swinhoe having so described some specimens from Northern China; but I have not found this to be confirmed in those skins from Central Asia which I have seen. Shortly before leaving London, in 1878, Mr. Charles Reuss, furrier, in Bond Street, showed me a beautiful skin with deep soft hair, abundantly striped on a rich burnt sienna ground, admirably relieved by the pure white of the lower parts. That light-coloured specimens are found is true, but I doubt whether they are more common than the others. Of the varieties in India it is more difficult to speak. Most sportsmen recognise two (some three)—the stout thick-set tiger of hilly country, and the long-bodied lankier one of the grass jungles in the plains. Such a division is in consonance with the ordinary laws of nature, which we also see carried out in the thick-set muscular forms of the human species in mountain tracts.

Some writers, however, go further, and attempt subdivisions more or less doubtful. I knew the late Captain J. Forsyth most intimately for years. We were in the same house for some time. I took an interest in his writings, and helped to illustrate his last work, and I can bear testimony to the general accuracy of his observations and the value of his book on the Highlands of Central India; but in some things he formed erroneous ideas, and his three divisions, based on the habits of the tiger, is, I think, open to objection, as tending to create an idea of at least two distinct varieties.

Native shikaris, he says, recognise two kinds—the Lodhia Bagh and the Oontia Bagh (which last I may remind my readers is one of the names of the lion). The former is the game-killing tiger, retired in his habits, living chiefly among the hills, retreating readily from man. "He is a light-made beast, very active and enduring, and from this, as well as his shyness, generally difficult to bring to bag."

I grant his shyness and comparative harmlessness (I once met one almost face to face)—and the nature of the ground he inhabits increases the difficulty in securing him—but I do not think he physically differs from his brother in the cattle districts. Mr. Sanderson says one of the largest tigers he had killed was a pure game-killer.

"The cattle-lifter again," says Forsyth, "is usually an older and heavier animal (called Oontia Bagh, from his faintly striped coat, resembling the colour of a camel), very fleshy and indisposed to severe exertion."

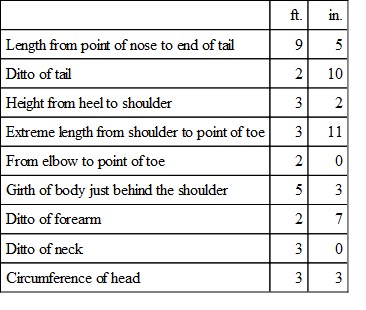

His third division is the man-eater. However, this is merely a classification on the habits of the same animal. I think most Central India sportsmen will agree with me when I say that many a young tiger is a cattle-eater, with a rich coloured hide, although it often happens that an old tiger of the first division, when he finds his powers for game failing by reason of age or increased bulk, transfers himself from the borders of the forest to the vicinity of grazing lands and villages, and he ultimately may come into the third division by becoming a man-eater. So that the Lodhia becomes the Oontia (for very old tigers become lighter in colour), and may end by being an Adam-khor, or man-eater. Tigers roam a great deal at times, and if in their wanderings they come to a suitable locality with convenience of food and water, they abide there, provided there be no occupant with a prior claim and sufficient power to dispute the intrusion. We had ample proof of this at Seonee. Close to the station, that is, within a short ride, were several groups of hills which commanded the pasture lands of the town. Many a tiger has been killed there, the place of the slain one being occupied ere long by another. On the other hand, if a tiger be accommodated with lodgings to his liking, he will stay there for years, roaming a certain radius, but returning to his home; and it is the knowledge of this that so often enables the hunter to compass his destruction. As long therefore as there are human habitations, with their usual adjuncts of herds and flocks, within a dozen miles of the jungle tiger's haunts, so long there will always be the transition from the game-killer to the cattle-lifter and the man-eater. Colour and striping must also be thrown out of the question, for no two individuals of any variety agree, and the characteristics of shade and marking are common to all kinds. The only reliable data therefore are derived from measurements, and from these it may be proved that the grass-jungle tiger of Bengal, though the longer animal, is yet inferior in all round measurement and probably in weight to the tiger of hilly country—see Mr. Shillingford's comparison quoted by me above. Let also any one compare the following measurements of one given by Colonel Walter Campbell with a tiger of equal length shot in the grassy plains of Bengal:—

This is a remarkably short-tailed tiger. If the concurrence of evidence establishes the difference beyond doubt, then we may say that there are two varieties in India—the hill tiger, Felis tigris, var. montanus; and the other, inhabiting the alluvial plains of great rivers, Felis tigris, var. fluviatilis. Dr. Anderson says he has examined skulls and skins of those inhabiting the hill ranges of Yunnan, and can detect no difference from the ordinary Indian species.

The tigress goes with young for about fifteen weeks, and produces from two to five at a birth. I remember once seeing four perfectly formed cubs, which would have been born in a day or two, cut from a tigress shot by my brother-in-law Col. W. B. Thomson in the hills adjoining the station of Seonee. I had got off an elephant, and, running up the glen on hearing the shots, came unpleasantly close to her in her dying throes. When about to bring forth, the tigress avoids the male, and hides her young from him. The native shikaris say that the tiger kills the young ones if he finds them. The mother is a most affectionate parent as a rule, and sometimes exhibits strange fits of jealousy at interference with her young. I heard an instance of this some years ago from my brother, Mr. H. B. Sterndale, who, as one of the Municipal Commissioners of Delhi, took a great interest in the collection of animals in the Queen's Gardens there. Both tiger and leopard cubs had been born in the gardens, and the mother of the latter shewed no uneasiness at her offspring being handled by strangers as they crept through the bars and strayed about; but one day, a tiger cub having done the same, the tigress exhibited great restlessness, and, on the little one's return, in a sudden accession of jealous fury she dashed her paw on it and killed it. I am indebted to Mr. Shillingford for a long list of tigresses with cubs killed during the years 1866 to 1880. Out of 53 cubs (18 mothers) 29 were males and 22 females, the sex of two cubs not being given. This tends to prove that there are an equal number of each sex born—in fact here the advantage is on the side of the males. I have heard it asserted that tigresses are more common, and native shikaris account for it by saying that the male tiger kills the cubs of his own sex; but I have not seen anything to justify this assertion, or the fact of there being a preponderance of females. Mr. Sanderson, however, writes: "Male and female cubs appear to be in about equal proportions. How it is that amongst mature animals tigresses predominate so markedly I am unable to say."

Tigresses have young at all seasons of the year, and they breed apparently only once in three years, which is about the time the cubs remain with their mother.

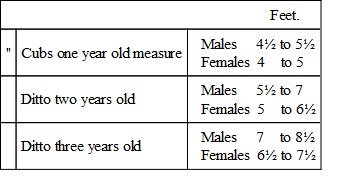

For the following interesting memorandum I have to thank Mr. Shillingford:—

"When they reach three years of age they lose their 'milk' canines, which are replaced by the permanent fangs, and at this period the mother leaves them to cater for themselves."

The cubs are interesting pets if taken from the mother very young. I have reared several, but only kept one for any length of time. I have given a full description of Zalim and his ways in 'Seonee.' He was found by my camp followers with another in a nullah, and brought to me. The other cub died, but Zalim lived to grow up into a very fine tiger, and was sent to England. I never allowed him to taste raw flesh. He had a little cooked meat every day, and as much milk as he liked to drink, and he throve well on this diet. When he was too large to be allowed to roam about unconfined I had a stout buffalo-leather collar made for his neck, and he was chained to a stump near the cook-room door. With grown-up people he was perfectly tame, but I noticed he got restless when children approached him, and so made up my mind to part with him before he did any mischief.

I know nothing of the habits of the tiger of the grass plains, but those of the hill tiger are very interesting, the cattle lifter especially, as he is better known to men. Each individual has his special idiosyncrasy. I wrote of this once before as follows: "Strange though it may seem to the English reader that a tiger should have any special character beyond the general one for cruelty and cunning, it is nevertheless a fact that each animal has certain peculiarities of temperament which are well known to the villagers in the neighbourhood. They will tell you that such a one is daring and rash; another is cunning and not to be taken by any artifice; that one is savage and morose; another is mild and harmless. There are few villages in the wilder parts of the Seonee and Mandla districts without an attendant tiger, which undoubtedly does great damage in the way of destroying cattle, but which avoids the human inhabitants of the place. So accustomed do the people get to their unwelcome visitor that we have known the boys of a village turn a tiger out of quarters which were reckoned too close, and pelt him with stones. On one occasion two of the juvenile assailants were killed by the animal they had approached too near. Herdsmen in the same way get callous to the danger of meddling with so dreadful a creature, and frequently rush to the rescue of their cattle when seized. On a certain occasion one out of a herd of cattle was attacked close to our camp, and rescued single-handed by it's owner, who laid his heavy iron-bound staff across the tiger's back; and, on our rushing out to see what was the matter, we found the man coolly dressing the wounds of his cow, muttering to himself: 'The robber, the robber! My last cow, and I had five of them!' He did not seem to think he had done anything wonderful, and seemed rather surprised that we should suppose that he was going to let his last heifer go the way of all the others.

"It is fortunate for these dwellers in the backwoods that but a small percentage of tigers are man-eaters, perhaps not five per cent., otherwise village after village would be depopulated; as it is the yearly tale of lives lost is a heavy one."12

Tigers are also eccentric in their ways, showing differences in disposition under different circumstances. I believe that many a shikari passes at times within a few yards of a tiger without knowing it, the tendency of the animal being to crouch and hide until the strange-looking two-legged beast has passed. The narrowest escape I ever had is an instance. I had hunted a large tiger, well known for the savageness of his disposition, on foot from ravine to ravine on the banks of the Pench, one hot day in June, and, giving him no rest, made sure of getting him about three o'clock in the afternoon. He had been seen to slip into a large nullah, bordered on one side by open country, a small water-course draining into it from the fields; here was one large beyr bush, behind which I wished to place myself, but was persuaded by an old shikari of great local reputation to move farther on. Hardly had we done so when our friend bounded from under the bush and disappeared in a thicket, where we lost him. Ten days after this he was killed by a friend and myself, and he sustained his savage reputation by attacking the elephant without provocation—a thing a tiger seldom does. I had hunted this animal several times, and on one occasion saw him swim the Pench river at one of its broadest reaches. It was the only time I had seen a tiger swim, and it was interesting to watch him powerfully breasting the stream with his head well up. Tigers swim readily, as is well known. I believe it is not uncommon to see them take to the water in the Sunderbunds; and a recent case may be remembered when two of them escaped from the King of Oude's Menagerie, and one swam across the Hooghly to the Botanical Gardens.

There has been some controversy about the way in which tigers kill their prey. I am afraid I cannot speak definitely on the subject, although I have on several occasions seen tigers kill oxen and ponies. I do not think they have a uniform way of doing it, so much depends upon circumstance—certain it is that they cannot smash in the head of a buffalo with a stroke, as some writers make out, but yet I have known them make strokes at the head, in a running fight, for instance, between a buffalo and a tiger—in which the former got off—and in the case of human beings. Of two men killed by the same tiger, one had his skull fractured by a blow; the other, who was killed as we were endeavouring to drive the tiger out of the village, was seized by the loins. He died immediately; the man with the fractured skull lingered some hours longer. Another case of a stroke at the head happened once when I had tied out a pony for a tiger that would not look at cows, over which I had sat for several successive nights. A tiger and tigress came out, and the former made a rush at the tattu, who met him with such a kick on the nose that he drew back much astonished; the tigress then dashed at the pony, and I, wishing if possible to save the plucky little animal's life, fired two barrels into her, rolling her over just as she struck at his head. But it was too late; the pony dropped at the blow and died—not from concussion, however, but from loss of blood, for the jugular vein had been cut open as though it had been done with a knife. So much for the head stroke, which is, I may say, exceptional. As a general rule I think the tiger bears down his victim by sheer weight, and then, by some means which I should hesitate to define, although I have seen it, the head is wrenched back, so as to dislocate the vertebræ. One evening two cows were killed before me. I was going to say the tiger sprang at one, but correct myself—it is not a spring, but a rush on to the back of the animal; he seldom springs all fours off the ground at once. I have never seen a tiger get off his hind legs except in bounding over a fallen tree, or in and out of a ravine. In this case he rushed on to the cow and bore it to the ground; there was a violent struggle, and in the dusky light I could not tell whether he used his mouth or paws in wrenching back the head, which went with a crack. The thing was done in a minute, when he sprang once more to his feet, and the second cow was hurled to the ground in like manner. As his back was turned to me I fired somewhat hastily, thinking to save the cow, but only wounded the tiger, which I lost. Both the cows, however, had their necks completely broken. I cannot now remember the position of the fang-marks in the throat. On another occasion I came across five out of a herd that had been killed, probably by young tigers; every one had the neck broken.

Mr. Sanderson says that herdsmen have described to him how they have noticed the operation: "Clutching the bullock's fore-quarters with his paws, one being generally over the shoulder, he seizes the throat in his jaws from underneath and turns it upwards and over, sometimes springing to the far side in doing so, to throw the bullock over and give the wrench which dislocates its neck. This is frequently done so quickly that the tiger, if timid, is in retreat again almost before the herdsmen can turn round." This account seems reliable. A tiger may seize by the nape in order to get a temporary purchase, but it would be awkward for him to pull the head back far enough to snap the vertebral column.

Now for a few remarks in conclusion. I have written more on the subject than I intended. That tigers are carrion feeders is well known, but that sometimes they prefer high meat to fresh I had only proof of once. A tiger killed a mare and foal, on which he feasted for three days; on the fourth nothing remaining but a very offensive leg; we tied out a fine young buffalo calf for him within a yard or two of the savoury joint. The tiger came during the night and took away the leg, without touching the calf; and, devouring it, fell asleep, in which condition we, having tracked him up the nullah, found and killed him.

The tiger is not always monarch over all the beasts of the field. He is positively afraid of the wild dog (Cuon rutilans), which readily attacks him in packs. Then he often finds his match in the wild boar. I have myself seen an instance of this, in which the tiger was not only ripped to death, but had his chest-bone gnawed and crushed, evidently after life was extinct.

Buffalos in herds hesitate not in attacking a tiger; and I saw one instance of their saving their herdsman from a man-eater. My camp was pitched on the banks of a stream under some tall trees. I had made a détour in order to try and kill this man-eater, and had sent on a hill tent the night before. I was met in the morning by the khalasi in charge, with a wonderful story of the tiger having rushed at him, but as the man was a romancer I disbelieved him. On the other side of the stream was a gentle slope of turf and bushes, rising gradually to a rocky hill. The slope was dotted with grazing herds, and here and there a group of buffalos. Late in the afternoon I heard some piercing cries from my people of "Bagh! Bagh!" The cows stampeded, as they always do. A struggle was going on in the bush, with loud cries of a human voice. The buffalos threw up their heads, and, grunting loudly, charged down on the spot, and then in a body went charging on through the brushwood. Other herdsmen and villagers ran up, and a charpoy was sent for and the man brought into the village. He was badly scratched, but had escaped any serious fang wounds from his having, as he said, seen the tiger coming at him, and stuffed his blanket into his open mouth, whilst he belaboured him with his axe. Anyhow but for his buffalos he would have been a dead man in three minutes more.

THE PARDS OR PANTHERSTo these are commonly assigned the name of Leopard, which ought properly to be restricted to the hunting leopard (Felis jubata), to which we have also misappropriated the Indian name Chita, which applies to all spotted cats, Chita-bagh being spotted tiger. The same term, derived from the adjective chhita, spotted or sprinkled, applies in various forms to the other creatures, such as Chital, the spotted deer (Axis), Chita-bora, a kind of speckled snake, &c. Leopardus or lion-panther was, without doubt, the name given by the ancients to the hunting leopard, which was well known to them from its extending into Africa and Arabia. Assuredly the prophet Habakkuk spoke of the hunting chita when he said of the Chaldæans: "That bitter and hasty nation . . . their horses also are swifter than the leopards," for the pard is not a swift animal, whereas the speed of the other is well known.