полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

Dr. Anderson, who distinguishes it by the feature of its skull from the two preceding species, says: "It may be that this otter has a north-westerly distribution, and that it is the species which occurs in the lake at Mount Abu in Rajputana, and also in Sindh and in the Indus."

NO. 198. LUTRA AUROBRUNNEAHABITAT.—Nepal.

DESCRIPTION.—Fur of a rich ferruginous brown colour, the upper surface of the head being a deeper brown than the back; the nose is bare; the ears are small and pointed posteriorily. All the strong bristles of the moustache, eyes, cheeks, and chin, are dark brown; claws as in Lutra (Anderson). Hodgson says it has a more vermiform body than the rest of Indian otters; tail less than two thirds of the body; nails and toes feebly developed (whence it is classed by Gray in the next genus); fur long and rough, rich chestnut-brown above, golden red below and on the extremities.

SIZE.—Head and body, 20 to 22 inches; tail, 12 to 13 inches.

GENUS AONYX—CLAWLESS OTTERSMuzzle bald, oblong; skull broad, depressed, shorter and more globose than in Lutra; the molars larger than in the last genus; flesh tooth larger, and with a large internal lobe; first upper premolar generally absent; feet oblong, elongate; toes slender and tapering; claws rudimentary.

NO. 199. AONYX LEPTONYXThe Clawless Otter (Jerdon's No. 102)NATIVE NAMES.—Chusam, Bhotia; Suriam, Lepcha.

HABITAT.—Throughout the Himalayas, also in Lower Bengal and in Burmah.

DESCRIPTION.—"Above earthy brown or chestnut brown; lips, sides of head, chin, throat, and upper part of breast white, tinged with yellowish-grey. In young individuals the white of the lower parts is less distinct, sometimes very pale brownish."—Jerdon.

SIZE.—Head and body, 24 Inches; tail, 13.

Mason speaks of this species as common in Burmah, and McMaster mentions his having seen in the Sitang River a colony of white-throated otters smaller than L. nair, though larger than L. aurobrunnea, but he did not secure specimens.

ÆLUROIDEAThis section includes the Cat family (Felidæ); the Hyænas (Hyænidæ); two families unknown in India, viz. the Cryptoproctidæ and the Protelidæ; and the Civet family (Viverridæ).

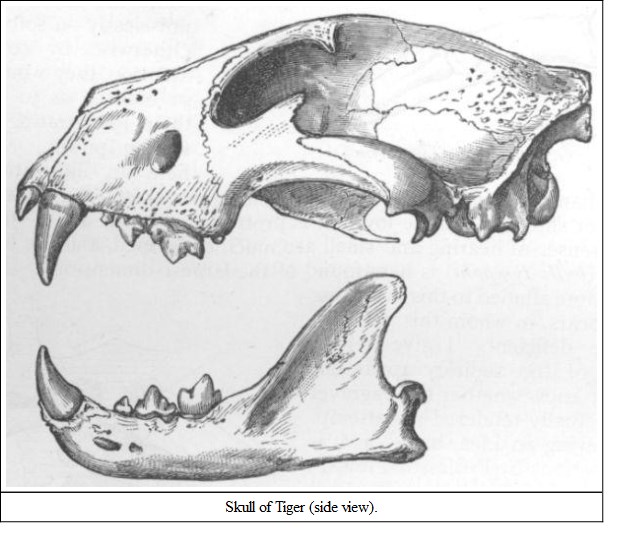

FELIDÆ—THE CAT FAMILYThis family contains the typical carnivores. There is in them combined the greatest power of destruction, accompanied by the simplest mechanism for producing it. All complications of dentition and digestion disappear. Here are the few scissor-like teeth with the enormous canines, the latter for holding and piercing the life out of their prey, the former for chopping up the flesh into suitable morsels for swallowing. Then the stomach is a simple sac, undivided into compartments, and the intestine is short, not more than three times the length of the body, instead of being some twenty times longer, as in some herbivores. This family has the smallest number of molars, a class of tooth which would indeed be useless, for the construction of the feline jaw precludes the possibility of grinding, and therefore a flat-crowned tuberculous tooth would be out of place. As I have before described it, the jaw of a tiger is incapable of lateral motion. The condyle of the lower jaw is so broad, and fits so accurately into its socket, the glenoid cavity, that there can be no departure from the up and down scissor-like action. The true Cats have, therefore, only one molar on each side of each jaw; those in the upper jaw being merely rudimentary, and placed almost at right angles to the rest of the teeth, and seem apparently of little use; those of the lower jaw are large and trenchant, cutting against the edge of the third upper premolar.

It may interest my readers to know which are premolars and which are molars. This can be decided only by dissection of the jaw of a young animal. True molars only appear as the animal approaches the adult stage. They are never shed, as are all the rest of the teeth, commonly called milk teeth. The deciduous or milk teeth are the incisors, canines, and premolars; they drop out and are replaced, and behind the last premolar comes up the permanent molar.

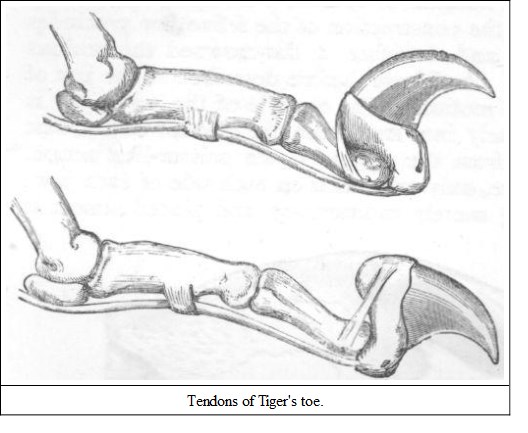

Another peculiar feature of the Cat family is the power of sheathing their talons. Claws to a cat are of as great importance to him in the securing of his prey as are his teeth. The badger is a digger, Hodge, who carries his mattock on his shoulder; but the feline is the free-lance whose sword must be kept keen in its scabbard, so by a peculiar arrangement of muscles the points of the claws are kept off the ground, while the animal treads noiselessly on soft pads. Otherwise by constant abrasion they would get so blunted as to fail in their penetrating and seizing power. I give here an illustration of the mechanism of the feline claw. In the upper sketch the claw is retracted or sheathed; in the lower it is protruded as in the act of striking.

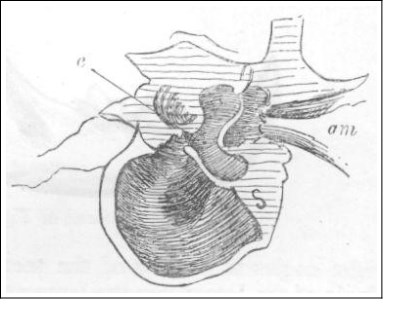

The senses of hearing and smell are much developed, and the bulb of the ear (bulla tympani) is here found of the largest dimensions. I have once before alluded to this in writing of the bears, in whom this arrangement is deficient. I give here a section of the auditory apparatus. I do not know whether the engraver has effectually rendered my attempt at conveying an idea, based as it is on dissections by Professor Flower; but if he has failed I think the fault lies in the shakiness of my hand in attempting the fine shading after nearly breaking a saw and losing my temper over a very tough old skull which I divided before commencing my illustration. The great cavity is the bulla tympani or bulb of the ear; a m is the auditory meatus or external hole of the ear. On looking into a dry skull the passage seems to be of no great depth, nor can an instrument be passed directly from the outside into the great tympanic cavity, the hindrance being a wall of bone, s, the septum which divides the bulla into two distinct chambers, the reason for which is not very clear, except that one may suppose it to be in some measure for acoustic purposes, as all animals with this development are quick of hearing. The communication between the two chambers lies in a narrow slit over the septum, the Eustachian tube, e, being on the outside of the septum and between it and the tympanum or ear drum, t.

The above are the chief characteristics of the family. For the rest we may notice that they have but a rudimentary clavicle imbedded among the muscles; the limbs are comparatively short, but immensely muscular; the body lithe and active; the foot-fall noiseless; the tongue armed with rough papillæ, which enables them to rasp the flesh off bones, and their vision is adapted for both night and day.

None of them are gregarious, as in the case of dogs and wolves. One hears sometimes of a limited number of lions and tigers being seen together, but in most cases they belong to one family, of which the junior members have not been "turned off on their own hook" as yet.

GENUS FELISNO. 200. FELIS LEOThe Lion (Jerdon's No. 103)NATIVE NAMES.—Sher-babbar, Singh, Unthia-bagh.

HABITAT.—Guzerat and Central India.

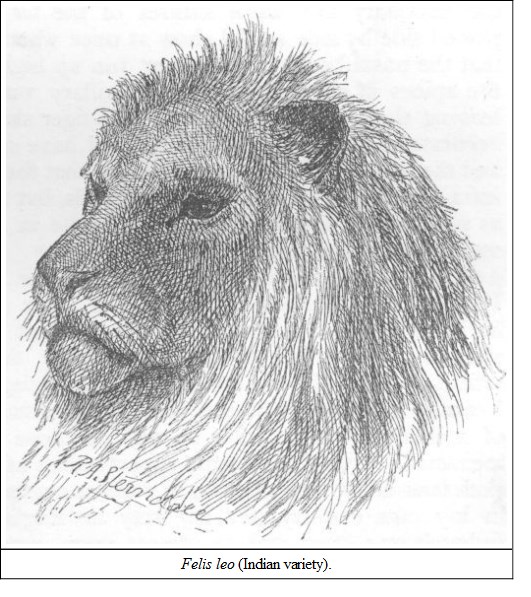

DESCRIPTION.—The lion is almost too well known to need description, and there is little difference between the Asiatic and African animal. It may, however, be generally described as being distinguished from other Cats by its uniform tawny colour, flatter skull, which gives it a more dog-like appearance, the shaggy mane of the male, and by the tufted tail of both sexes.

SIZE.—From nose to insertion of tail, 6 to 6½ feet; tail, 2½ to 3 feet; height, 3½ feet.

The weight of one measured by Captain Smee, 8 feet 9½ inches, was (excluding the entrails) thirty-five stone. This must be the one alluded to by Jerdon, but he does not state the extraction of the viscera, which would add somewhat to the weight.

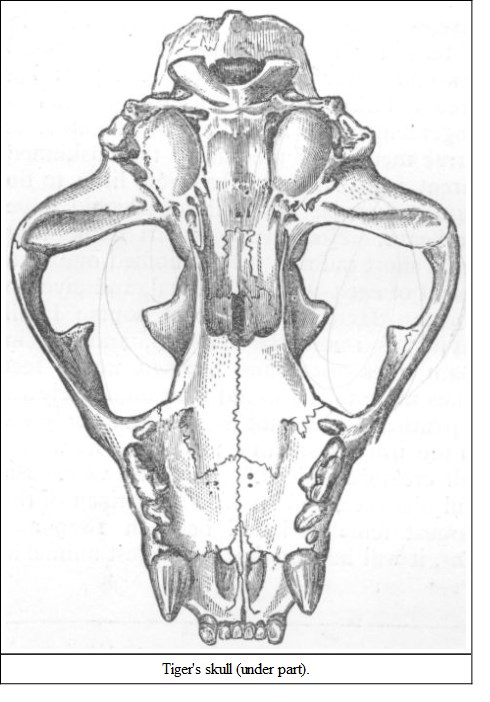

Young lions when born are invariably spotted; and Professor Parker states that there were in the Zoological Gardens in 1877 three lions which were born in the menagerie about ten years previously, and which showed "indistinct, though perfectly evident, spots of a slightly darker tawny than the general ground-tint on the belly and flanks." He adds: "This is also the case with the puma, and it looks very much as if all the great Cats were descended from a spotted ancestor." The more dog-like head of the lion is well known to all who have studied the physiognomy of the Cats, and I have not only noticed it in drawing the animal, but have seen it alluded to in the writings of others. It was not, however, till lately that I had an opportunity of comparing the skulls of the lion and tiger in the Calcutta Museum, and I am indebted to Mr. Cockburn of the museum, not only for the trouble he took in getting out the various skulls, but for his assistance in pointing out certain peculiarities known to him, but of which I was at the time ignorant. That the skull of the lion is flatter than, and wants the bold curve of, those of the tiger, leopard and jaguar, is a well-known fact, but what Mr. Cockburn pointed out to me was the difference in the maxillary and nasal sutures of the face. A glance at two skulls placed side by side would show at once what I mean. It would be seen that the nasal bones of the tiger run up higher than those of the lion, the apices of whose nasal and maxillary sutures are on a level. On leaving the museum I compared the tiger skulls in my possession with accurate anatomical drawings which I have of the osteology of the lion, and the result was the same. It is said that there is also a difference in the infra-orbital foramen of the two animals, but this I have failed to detect as yet, though asserted by De Blainville in his magnificent work on osteology ('Ostéographie').

From all that has been written of the African and Indian lions I should say that the tiger was the more formidable of the two, as he is, I believe, superior in size. About twenty-two years ago my attention was drawn to this subject by the perusal of Mr. Blyth's article on the Felidæ in the old India Sporting Review of 1856-57. If I am not mistaken there was at that time (1861) a fine skeleton of a lion in the museum, as well as those of several tigers, which I measured. I had afterwards opportunities of observing and comparing skeletons of the two animals in various museums in Europe, though not in my own country, for my stay in England on each occasion of furlough was brief, and in almost every instance I found the tiger the larger of the two. The book in which I recorded my observations, and which also contained a number of microscopic drawings of marine infusoria, collected during a five months' voyage, was afterwards lost, so I cannot now refer to my notes.

I believe there was once a case of a fair fight between a well-matched lion and tiger in a menagerie (Edmonds's, I think). The two, by the breaking of a partition, got together, and could not be separated. The duel resulted in the victory of the tiger, who killed his opponent.

The lion seems to be dying out in India, and it is now probably confined only to Guzerat and Cutch. I have not been an attentive reader of sporting magazines of late years, and therefore I cannot call to mind any recent accounts of lion-killing in India, if any such have been recorded. At the commencement of this century lions were to be found in the North-West and in Central India, including the tract of country now termed the Central Provinces. In 1847 or 1848 a lioness was killed by a native shikari in the Dumoh district. Dr. Spry, in his 'Modern India,' states that, when at Saugor in the Central Provinces in 1837, the skin of a full-grown male lion was brought to him, which had been shot by natives in the neighbourhood. He also mentions another lioness shot at Rhylee in the Dumoh district in 1834, of which he saw the skin. Jerdon says that tolerably authentic intelligence was received of the presence of lions near Saugor in 1856; and whilst at Seonee, within the years 1857 to 1864, I frequently heard the native shikaris speak of having seen a tiger without stripes, which may have been of the present species. The indistinct spots on the lion's skin (especially of young lions), to which I have before alluded, were noticed in the skin of the lioness shot at Dumoh in 1847. The writer says: "when you place it in the sun and look sideways at it, some very faint spots (the size of a shilling or so) are to be seen along the belly."

Lions pair off at each season, and for the time they are together they show great attachment to each other, but the male has to fight for his spouse, who bestows herself on the victor. They then live together till the young are able to shift for themselves. The lioness goes with young about fifteen or sixteen weeks, and produces from two to six at a litter. But there is great mortality among young lions, especially about the time when they are developing their canine teeth. This has been noticed in menageries, confirming a common Arab assertion. In the London Zoological Gardens, during the last twenty years, there has been much mortality among the lion cubs by a malformation of the palate. It is a curious fact that lions breed more readily in travelling menageries than in stationary ones.

NO. 201. FELIS TIGRISThe Tiger (Jerdon's No. 104)NATIVE NAME.—Bagh, Sher, Hindi; Sela-vagh, Go-vagh, Bengali; Wuhag, Mahrathi; Nahar in Bundelkund and Central India; Tut of the hill people of Bhagulpore; Nongya-chor in Gorukpore; Puli in Telegu and Tamil; also Pedda-pulli in Telegu; Parain-pulli in Malabar; Huli in Caranese; Tagh in Tibet; Suhtong in Lepcha; Tukh in Bhotia.

These names are according to Jerdon. Bagh and Sher all Indian sportsmen are familiar with. The Gonds of the Central Provinces call it Pullial, which has an affinity with the southern dialects.

HABITAT.—The tiger, as far as we are concerned, is known throughout the Indian peninsula and away down the eastern countries to the Malayan archipelago. In Ceylon it is not found, but it extends to the Himalayas, and ranges up to heights of 6000 to 8000 feet. Generally speaking it is confined to Asia, but in that continent it has a wide distribution. It has been found as far north as the island of Saghalien, which is bisected by N. L. 50°. This is its extreme north-eastern limit, the Caspian Sea being its westerly boundary. From parallel 50° downwards it is found in many parts of the highlands of central Asia.

DESCRIPTION.—A large heavy bodied Cat, much developed in the fore-quarters, with short, close hair of a bright rufous ground tint from every shade of pale yellow ochre to burnt sienna, with black stripes arranged irregularly and seldom in two individuals alike, the stripes being also irregular in form, from single streaks to loops and broad bands. In some the brows and cheeks are white, and in all the chin, throat, breast, and belly are pure white. All parts, however, whether white or rufous, are equally pervaded by the black stripes. The males have prolonged hairs extending from the ears round the cheeks, forming a ruff, or whiskers as they are sometimes called, although the true whiskers are the labial bristles. The pupil of the tiger's eye is round, and not vertical, as stated by Jerdon.

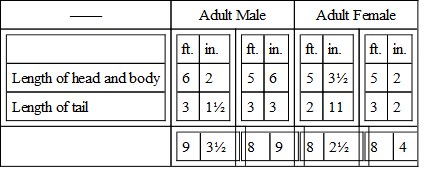

SIZE.—Here we come to a much-vexed question, on which there is much divergence of opinion, and the controversy will never be decided until sportsmen have adopted a more correct system of measurement. At present the universal plan is to measure the animal as it lies on the ground, taking the tape from the tip of the nose to the end of the tail. I will undertake that no two men will measure the same tiger with equal results if the body be at all disturbed between the two operations. If care be not taken to raise the head so as to bring the plane of the skull in a line with the vertebræ, the downward deflection will cause increased measurement. Let any one try this on the next opportunity, or on the dead body of a cat. Care should be taken in measuring that the head be raised, so that the top of the skull be as much as possible in a line with the vertebræ. A stake should be then driven in at the nose and another close in at the root of the tail, and the measurement taken between the two stakes, and not round the curves. The tail, which is an unimportant matter, but which in the present system of measurement is a considerable factor, should be measured and noted separately. I am not a believer in tails (or tales), and have always considered that they should be excluded from measurements except as an addition. I spoke of this in 'Seonee' in the following terms: "If all tigers were measured honestly, a twelve-foot animal would never be heard of. All your big fellows are measured from stretched skins, and are as exaggerated as are the accounts of the dangers incurred in killing them—at least in many cases. But even the true method of measuring the unskinned animal is faulty; it is an apparent fact that a tail has very little to do with the worthiness of a creature, otherwise our bull-dogs would have their caudal appendages left in peace. Now every shikari knows that there may be a heavy tiger with a short tail and a light bodied one with a long tail. Yet the measurement of each would be equal, and give no criterion as to the size of the brute. Here's this tiger of yours; I call him a heavy one, twenty-eight inches round the fore-arm, and big in every way, yet his measurement does not sound large (it was 9 feet 10 inches), and had he six inches more tail he would gain immensely by it in reputation. The biggest panther I ever shot had a stump only six inches long; and according to the usual system of measuring he would have read as being a very small creature indeed." Tails do vary. Sir Walter Elliot was a very careful observer, and in his comparison of the two largest males and two largest females, killed between 1829 and 1833, out of 70 to 80 specimens, it will be seen that the largest animal in each sex had the shortest tail:—

Campbell, in his notes to 'The Old Forest-Ranger,' gives the dimensions of a tiger of 9 ft. 5 in. of which the tail was only 2 ft. 10 in. From the other detailed measurements it must have been an enormous tiger. The number of caudal vertebræ in the tiger and lion should be twenty-six. I now regret that I did not carefully examine the osteology of all short-tailed tigers which I have come across, to see whether they had the full complement of vertebræ. The big tiger in the museum is short by the six terminal joints = three inches. This may have occurred during life, as in the case of the above-quoted panther; anyhow the tail should, I think, be thrown out of the calculation. Now as to the measurement of the head and body, I quite acknowledge that there must be a different standard for the sportsman and for the scientific naturalist. For the latter the only reliable data are derived from the bones. Bones cannot err. Except in very few abnormal conditions the whole skeleton is in accurate proportion, and it has lately struck me that from a certain measurement of the skull a true estimate might be formed of the length of the skeleton, and approximately the size of the animal over the muscles. I at first thought of taking the length of the skull by a craniometer, and seeing what portion of the total length to the posterior edge of the sacrum it would be, but I soon discarded the idea on account of the variation in the supra-occipital process.

I then took the palatal measurement, from the outer edge of the border in which the incisors are set to the anterior inside edge of the brain-hole, or foramen magnum, and I find that this standard is sufficiently accurate, and is 5·50 of the length taken from the tip of the premaxillaries to the end of the sacrum. Therefore the length of this portion of any tiger's skull multiplied by 5·50 will give the measurement of the head and body of the skeleton.

For the purpose of working out these figures I applied to all my sporting friends for measurements of their largest skulls, with a view to settling the question about tigers exceeding eleven feet. The museum possesses the skeleton of a tiger which was considered one of the largest known, the cranial measurement of whose skull is 14·50 inches, but the Maharajah of Cooch Behar showed me one of his skulls which exceeded it, being 15 inches. Amongst others I wrote to Mr. J. Shillingford of Purneah, and he most kindly not only drew up for me a tabular statement of the dimensions of the finest skulls out of his magnificent collection, but sent down two for my inspection. Now in the long-waged war of opinion regarding the size of tigers I have always kept a reserved attitude, for if I have never myself killed, or have seen killed by others, a tiger exceeding ten feet, I felt that to be no reason for doubting the existence of tigers of eleven feet in length vouched for by men of equal and in some cases greater experience, although at the same time I did not approve of a system of measurement which left so much to conjecture.

There is much to be said on both sides, and, as much yet remains to be investigated, it is to be hoped that the search after the truth will be carried on in a judicial spirit. I have hitherto been ranged on the side of the moderate party; still I was bound to respect the opinion of Sir Joseph Fayrer, who, as not only as a sportsman but as an anatomist, was entitled to attention; and from my long personal acquaintance I should implicitly accept any statement made by him. Dr. Jerdon, whom I knew intimately, was not, I may safely assert, a great tiger shikari, and he based his opinion on evidence and with great caution. Mr. J. Shillingford, from whom I have received the greatest assistance in my recent investigations, and who has furnished me with much valuable information, is on the other hand the strenuous assertor of the existence of the eleven-foot tiger, and with the magnificent skulls before me, which he has sent down from Purneah, I cannot any longer doubt the size of the Bengal tiger, and that the animals to which they belonged were eleven feet, measured sportsman fashion—that is round the curves. The larger of the two skulls measures 15·25 inches taken between two squares, placed one at each end; a tape taken from the edge of the premaxillaries over the curve of the head gives 17·37 inches; the width across the zygomatic arches, 10·50.10 The palatal measurement, which is the test I proposed for ascertaining the length of the skeleton, is 12·25, which would give 5 feet 7·37 inches; about 3¾ inches larger than the big skeleton in the Museum. This may seem very small for the body of an animal which is supposed to measure eleven feet, but I must remind my readers that the bones of the biggest tiger look very small when denuded of the muscles; and the present difficulty I have to contend with is how to strike the average rate for the allowance to be added to skeleton for muscles, the chief stumbling block being the system which has hitherto included the tail in the measurement. It all tigers had been measured as most other animals (except felines) are—i.e. head and body together, and then the tail separately—I might have had some more reliable data to go upon; but I hope in time to get some from such sportsmen as are interested in the subject. I have shown that the tail is not trustworthy as a proportional part of the total length; but from such calculations as I have been able to make from the very meagre materials on which I have to base them, I should allow one 2·50th part of the total length of skeleton for curves and muscles.