полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

Some authors contend that the weasel, though commonly referred to the genus Mustela, should be Putorius, which is an instance of the disagreement which exists among naturalists. I have however followed Gray in his classification, although perhaps Cuvier, who classes the weasels and pole-cats under the genus Putorius, has the claim of priority. Ray applied the name of Mustela to the restricted weasels, and Martes to the martens, but Cuvier gives Mustela to the martens, and brings the weasels and pole-cats together under Putorius.

NO. 180. MUSTELA (VISON: Gray) SUB-HEMACHALANAThe Sub-Hemachal Weasel (Jerdon's No. 97)NATIVE NAMES.—Zimiong, Bhotia; Sang-king, Lepcha; Kran or Gran, Kashmiri.

DESCRIPTION.—"Uniform bright brown, darker along the dorsal line; nose, upper lip, and forehead, with two inches of the end of the tail black-brown; mere edge of upper lip and whole of lower jaw hoary; a short longitudinal white stripe occasionally on the front of the neck, and some vague spots of the same laterally, the signs, I suspect, of immaturity; feet frequently darker than the body or dusky brown; whiskers dark; fur close, glossy and soft, of two sorts, or fine hair and soft wool, the latter and the hair basally of dusky hue, but the hair externally bright brown; head, ears, and limbs more closely clad than the body, tail more laxly, tapering to the point."—Hodgson.

SIZE.—Head and body about 12 inches; tail, 6 inches.

Jerdon calls this the Himalayan Weasel, but I have preferred to translate Hodgson's' name, which, I confess, puzzled me for some time till I found out there was a Hemachal range in Thibet.

NO. 181. MUSTELA (GYMNOPUS: Gray) KATHIAHThe Yellow-bellied Weasel (Jerdon's No. 98)NATIVE NAME.—Kathia-nyal, Nepalese.

HABITAT.—Nepal, Bhotan.

DESCRIPTION.—Dark brown; upper lip, chin, throat, chest, underside of body and front of thighs, bright yellow; tail dark brown, shorter than the body and head, tapering, and of the same colour to the tip; the soles of the hind feet bald; pads well developed, exposed.

SIZE.—Head and body, 10 inches; tail, 5 inches.

Hodgson states that a horribly offensive yellowish-grey fluid exudes from two subcaudal glands. He says that the Nepalese highly prize this little animal for its services in ridding houses of rats. It is easily tamed; and such is the dread of it common to all murine animals that not one will approach a house wherein it is domiciled. Rats and mice seem to have an instinctive sense of its hostility to them, so much so that when it is introduced into a house they are observed to hurry away in all directions, being apprised, no doubt, of its presence by the peculiar odour it emits. Its ferocity and courage are made subservient to the amusement of the rich, who train it to attack large fowls, geese, and even goats and sheep. It seizes these by the great artery of the neck, and does not quit its hold till the victim sinks exhausted from the loss of blood—a cruel pastime which one could only expect of a barbarous people.

NO. 182. MUSTELA (GYMNOPUS: Gray) STRIGIDORSAThe Striped Weasel (Jerdon's No. 99)HABITAT.—Sikim.

DESCRIPTION.—Dark chestnut-brown, with a narrow streak of long yellow hairs down the back; edge of upper lip, chin, throat, chest, and a narrow stripe down the centre of the belly, yellow, or yellowish-white.

SIZE.—Head and body, 12 inches; tail, 5½ inches without the hair, 6½ inches with it.

This is similar to the last, but is slightly larger, and distinguishable by the dorsal stripe.

NO. 183. MUSTELA ERMINEAThe Ermine or StoatHABITAT.—Europe, America and Asia (the Himalayas, Nepal, Thibet, Afghanistan).

DESCRIPTION.—Brown above; upper lip, chin, and lower surface of body, inside of limbs and feet yellowish-white; tail brown, with a black tip. In winter the whole body changes to a yellowish-white, with the exception of the black tip of the tail.

SIZE.—Head and body, about 10 inches; tail, 4½ inches.

This is about the best known in a general way from its fur being used as part of the insignia of royalty. The fur however only becomes valuable after it has completed its winter change. How this is done was for a long time a subject of speculation and inquiry. It is, however, now proved that it is according to season that the mode of alteration is effected. In spring the new hairs are brown, replacing the white ones of winter; in autumn the existing brown hairs turn white. Mr. Bell, who gave the subject his careful consideration, says that in Ross's first Polar expedition, a Hudson's Bay lemming (Myodes) was exposed in its summer coat to a temperature of 30° below zero. Next morning the fur on the cheeks and a patch on each shoulder had become perfectly white; at the end of the week the winter change was complete, with the exception of a dark band across the shoulder and a dorsal stripe.

Hodgson remarks that the Ermine is common in Thibet, where the skins enter largely into the peltry trade with China.

In one year 187,000 skins were imported into England.

NO. 184. MUSTELA (VISON: Gray) CANIGULAThe Hoary Red-necked WeaselHABITAT.—Nepal hills, Thibet.

DESCRIPTION.—Pale reddish-brown, scarcely paler beneath; face, chin, throat, sides of neck and chest white; tail half as long as body and head, concolorous with the back; feet whitish. Sometimes chest brown and white mottled, according to Gray. Hodgson, who discovered the animal, writes: "Colour throughout cinnamon red without black tip to the tail, but the chaffron and entire head and neck below hoary."

SIZE.—15½ inches; tail without hair 7½ inches, with hair 9½ inches.

NO. 185. MUSTELA STOLICZKANAHABITAT.—Yarkand.

DESCRIPTION.—Colour pale sandy brown above; hairs light at base, white below; tail concolorous with back; small white spot close to anterior angle of each eye; a sandy spot behind the gape; feet whitish.

SIZE.—Head and body, 12·2; tail, 3 inches, including hair.

NO. 186. MUSTELA (VISON) SIBIRICAHABITAT.—Himalayas (Thibet?); Afghanistan (Candahar).

DESCRIPTION.—Pale brown; head blackish, varied; spot on each side of nose, on upper and lower lips and front of chin, white; tail end pale brown like back, varies; throat more or less white.

This Weasel, described first by Pallas ('Specil Zool.' xiv. t. 4, f. 1.) was obtained in Candahar by Captain T. Hutton, who describes it in the 'Bengal Asiatic Society's Journal,' vol. xiv. pp. 346 to 352.

NO. 187. MUSTELA ALPINAThe Alpine WeaselHABITAT.—Said to be found in Thibet, otherwise an inhabitant of the Altai mountains.

DESCRIPTION.—Pale yellow brown; upper lip, chin, and underneath yellowish-white; head varied with black-tipped hairs; tail cylindrical, unicolour, not so long as head and body.—Gray.

NO. 188. MUSTELA HODGSONIHABITAT.—Himalaya, Afghanistan.

DESCRIPTION.—Fur yellowish-brown, paler beneath; upper part and side of head much darker; face, chin, and throat varied with white; tail long, and bushy towards the end.

NO. 189. MUSTELA (VISON) HORSFIELDIHABITAT.—Bhotan.

DESCRIPTION.—Uniform dark blackish-brown, very little paler beneath; middle of front of chin and lower lip white; whiskers black; tail slender, blackish at tip, half the length of head and body.

NO. 190. MUSTELA (GYMNOPUS) NUDIPES Gymnopus leucocephalus of GrayHABITAT.—Borneo, Sumatra, Java, but possibly Tenasserim.

DESCRIPTION.—Golden fulvous with white head.

As so many Malayan animals are found on the confines of Burmah, and even extending into Assam, it is probable that this species may be discovered in Tenasserim.

GENUS PUTORIUS—THE POLE-CATThis is a larger animal than the weasel, and in form more resembles the marten, except in the shortness of its tail; the body is stouter and the neck shorter than in Mustela; the head is short and ovate; the feet generally hairy, and the space between the pads very much so; the under side of the body is blackish; the fur is made up of two kinds, the shorter is woolly and lighter coloured than the longer, which is dark and shining.

The disgusting smell of the common Pole-cat (Putorius foetidus) is well known, and has become proverbial. In my county, as well as in many parts of England, the popular name is "foumart," which is said to be derived from "foul marten." The foumart is the special abhorrence of the game-keeper; it does more damage amongst game and poultry than any of the other Mustelidæ, and consequently greater pains are taken to trap and shoot it, in fact, so much so that I wonder that the animal is not now extinct in the British Isles. Professor Parker writes: "It has been known to kill as many as sixteen turkeys in a single night; and indeed it seems to be a point of honour with this bloodthirsty little creature to kill everything it can overpower, and to leave no survivors on its battle-fields." According to Bell, a female Pole-cat, which was tracked to her nest, was found to have laid up in a side hole a store of food consisting of forty frogs and two toads, all bitten through the brain, so that, though capable of living for some time, they were deprived of the power of escape. Now, this is a most wonderful instance of instinct bordering upon reason. Only the Reptilia can exist for any length of time after injury to the brain; to any of the smaller mammalia such a process as that adopted by the Pole-cat, would have resulted in instant death and speedy decomposition.

The Ferret (Putorius furo) is a domesticated variety of the Pole-cat, reputed to be of African origin. Certain it is that it cannot stand extreme cold like its wild cousin, and an English winter is fatal to it if not properly looked after. It inter-breeds with the Pole-cat.

Ferrets are not safe pets in houses where there are young children. Cases have been known of their attacking infants in the cradle, and severely lacerating them.

They are chiefly used for killing rats and driving rabbits out of burrows; in the latter case they are muzzled. As pets they are stupid, and show but little attachment. Forbearance as regards making its teeth meet in your fingers is, I think, the utmost you can expect in return for kindness to a ferret, and that is something, considering what a sanguinary little beast it is.

NO. 191. PUTORIUS LARVATUS vel TIBETANUSBlack-faced Thibetan Pole-catHABITAT.—Utsang in Thibet, also Ladakh.

DESCRIPTION.—"Tail one-third of entire length; soles clad; fur long; above and laterally sordid fulvous, deeply shaded on the back with black; below from throat backwards, with the whole limbs and tail, black; head pale, with a dark mask over the face."—Hodgson.

SIZE.—Head and body, 14 inches; tail, 6 inches, with hair 7 inches; palma, 1¾; planta, 2-3/8.

This animal, according to Gray, is synonymous with the Siberian Putorius Eversmannii, although the sudden contraction of the brain case in front, behind the orbit, mentioned of this species, is not perceptible in the illustration given by Hodgson of the skull of this Thibetan specimen. Horsfield, in his catalogue, states that the second specimen obtained by Captain R. Strachey in Ladakh, north of Kumaon, agreed in external character.

In some respects it is similar to the European Pole-cat, but as yet little is known of its habits.

NO. 192. PUTORIUS DAVIDIANUSHABITAT.—Moupin in Thibet.

DESCRIPTION.—Uniform fulvous brown, yellower under the throat; upper lip and round nostrils to corner of the eye white, darker on nose and forehead.

SIZE.—Head and body about 11½ inches; tail, 6½ inches.

This is one of the specimens collected by the Abbé David, after whom it is named. A fuller description of it will be found in Milne-Edwards's 'Recherches sur les Mammifères,' page 343. There is also a plate of the animal in the volume of illustrations.

NO. 193. PUTORIUS ASTUTUSHABITAT.—Thibet.

DESCRIPTION.—About the size of Ermine, but with a longer tail. Colour brown, the white of the chest tinted with yellow; tail uniform in colour, darker on head.

SIZE.—Head and body, 10 inches; tail, 4-1/5 inches.

This is also described and figured by Milne-Edwards.

NO. 194. PUTORIUS MOUPINENSISHABITAT.—Thibet.

DESCRIPTION.—Reddish-brown, white under the chin, and then again a patch on the chest.

LUTRIDÆ—THE OTTERSWe now come to the third group of the musteline animals, the most aquatic of all the Fissipedia—the Lutridæ or Otters—of which there are two great divisions, the common Otters (Lutra) and the Sea-Otters, (Enhydra). With the latter, a most interesting animal in all its ways, as well as most valuable on account of its fur, we have nothing to do. I am not aware that it is found in the tropics, but is a denizen of the North Pacific. Of Lutra we have several species in two genera. Dr. Gray has divided the Otters into no less than nine genera on three characteristics, the tail, feet, and muzzle, but these have been held open to objection. The classification most to be depended upon is the division of the tribe into long-clawed Otters (Lutra), and short or rudimentary-clawed Otters (Aonyx). The characteristics of the skulls confirm this arrangement, as the short-clawed Otters are distinguishable from the others by a shorter and more globose cranium and larger molars, and, as Dr. Anderson says, "the inner portion of the last molar being the largest part of the tooth, while in Lutra the outer exceeds the inner half; the almost general absence of the first upper premolar; and the rudimentary claws, which are associated with much more feebly-developed finger and toe bones, which are much tapered to a point, while in Lutra these bones are strong and well developed." Gray has separated a genus, which he called Pteronura, on account of a flattened tail arising from a longitudinal ridge on each side, but this flattening of the tail is common to all the genera more or less.

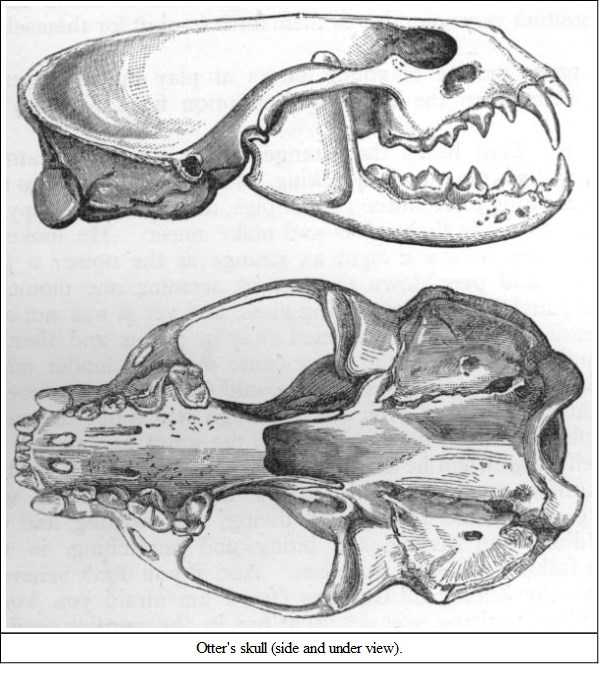

All the Otters, though active on land, are still only thoroughly at home in the water, and they are therefore specially constituted for such a mode of life. They have an elongated flattened form; webbed feet with short claws; compressed and tapering tail; dense fur of two kinds, one of long brown shining hairs; the under fur short and fine, impervious to wet, and well adapted for keeping an equality of temperature; the skull is peculiar, the brain case being very long, and compressed from above downwards; the facial portion forms only about one-fourth of the extreme length; the teeth are strong and sharp; the upper flesh tooth very large.

Dental formula: Inc., 3—3/3—3; can., 1—1/1—1; premolars, 4—4/3—3; molars, 1—1/2—2.

Jerdon states that the otter has a nictitating membrane or additional semi-transparent eyelid, similar to that in the eyes of birds, which he supposes is a defence to them under water; but I have not noticed this myself, and have failed to discover it in the writings of others. I should think that the vision of the animal under water would not require obscuring by a semi-transparent membrane, which none of the marine carnivora possess, though their eyes are somewhat formed for seeing better under water than when exposed to the full light above. Some idea of the rapidity of these animals in the water may be conceived when we think that their food is almost exclusively fish, of which they sometimes kill more than they can eat. They reside in burrows, making the entrance under water, and working upwards, making a small hole for the ventilation of their chamber. The female has about four or five young ones at a time, after a period of gestation of about nine weeks, and the mother very soon drives them forth to shift for themselves in the water.

For a pretty picture of young otters at play in the water, nothing could be better than the following description from Kingsley's 'Water Babies':—

"Suddenly Tom heard the strangest noise up the stream—cooing, grunting, and whining, and squeaking, as if you had put into a bag two stock-doves, nine mice, three guinea-pigs, and a blind puppy, and left them there to settle themselves and make music. He looked up the water, and there he saw a sight as strange as the noise: a great ball rolling over and over down the stream, seeming one moment of soft brown fur; and the next of shining glass, and yet it was not a ball, for sometimes it broke up and streamed away in pieces, and then it joined again; and all the while the noise came out of it louder and louder. Tom asked the dragon-fly, what it could be: but of course with his short sight he could not even see it, though it was not ten yards away. So he took the neatest little header into the water, and started off to see for himself; and when he came near, the ball turned out to be four or five beautiful creatures, many times larger than Tom, who were swimming about, and rolling, and diving, and twisting, and wrestling, and cuddling, and kissing, and biting, and scratching, in the most charming fashion that ever was seen. And if you don't believe me you may go to the Zoological Gardens (for I am afraid you won't see it nearer, unless, perhaps, you get up at five in the morning, and go down to Cordery's Moor, and watch by the great withy pollard which hangs over the back-water, where the otters breed sometimes), and then say if otters at play in the water are not the merriest, lithest, gracefullest creatures you ever saw."

Professor Parker, who also notices Kingsley's description,9 states that the Canadian otter has a peculiar habit in winter of sliding down ridges of snow, apparently for amusement. It, with its companions, scrambles up a high ridge, and then, lying down flat, glides head-foremost down the declivity, sometimes for a distance of twenty yards. "This sport they continue apparently with the keenest enjoyment, until fatigue or hunger induces them to desist."

The following are the Indian species; Lutra nair, L. simung vel monticola, L. Ellioti, and L. aurobrunnea of the long-clawed family, and Aonyx leptonyx of the short-clawed.

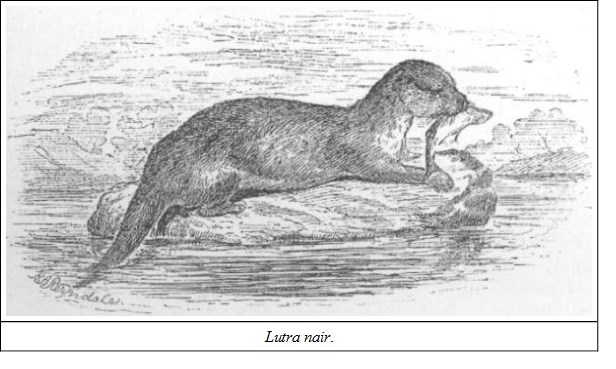

GENUS LUTRANO. 195. LUTRA NAIRThe Common Indian Otter (Jerdon's No. 100)NATIVE NAMES.—Ud or Ood, Ood-bilao, Panikutta, Hindi; Nir-nai, Canarese; Neeru-kuka, Telegu; Jal-manjer, Mahratti.

HABITAT.—India generally, Burmah and Ceylon.

DESCRIPTION.—Hair more or less brown above, sometimes with a chestnut hue, sometimes grizzled, or with a tinge of dun; yellowish-white, or with a fulvescent tinged white below; the throat, upper lip, and sides of head are nearly white; the line of separation of upper and lower parts not very distinctly marked. Some have whitish paws.

SIZE.—Head and body, 29 to 30 inches; tail about 17 inches.

This otter, which is synonymous with L. Indica, L. Chinensis and Hodgson's L. Tarayensis, is well known throughout India, and indeed far beyond Indian limits. They are generally found in secluded spots, in parties of about half a dozen hunting in concert. The young ones are easily tamed, and become greatly attached if kindly treated. I had one for some time. Jerdon tells a curious story of one he had, and which used to follow him in his walks. He says: "As it grew older it took to going about by itself, and one day found its way to the bazaar and seized a large fish from a moplah. When resisted, it showed such fight that the rightful owner was fain to drop it. Afterwards it took regularly to this highway style of living, and I had on several occasions to pay for my pet's dinner rather more than was necessary, so I resolved to get rid of it. I put it in a closed box, and, having kept it without food for some time, I conveyed it myself in a boat some seven or eight miles off, up some of the numerous back-waters on this coast. I then liberated it, and, when it had wandered out of sight in some inundated paddy-fields, I returned by boat by a different route. That same evening, about nine whilst in the town about one and a-half miles from my own house, witnessing some of the ceremonials connected with the Mohurrum festival, the otter entered the temporary shed, walked across the floor, and came and lay down at my feet!" It is to be hoped Dr. Jerdon did not turn him adrift again; such wonderful sagacity and attachment one could only expect in a dog.

McMaster gives the following interesting account of otters hunting on the Chilka Lake: "Late one morning I saw a party, at least six in number, leave an island on the Chilka Lake and swim out, apparently to fish their way to another island, or the mainland, either at least two miles off. I followed them for more than half the distance in a small canoe. They worked most systematically in a semicircle, with intervals of about fifty yards between each, having, I suppose, a large shoal of fish in the centre, for every now and then an otter would disappear, and generally, when it was again seen, it was well inside the semicircle with a fish in its jaws, caught more for pleasure than for profit, as the fish, as far as I could see, were always left behind untouched beyond a single bite. I picked up several of these fish, which, as far as I can recollect, were all mullet." Kingsley notices this. The old otter tells Tom: "We catch them, but we disdain to eat them all; we just bite out their soft throats and suck their sweet juice—oh, so good!" (and she licked her wicked lips)—"and then throw them away, and go and catch another."

General McMaster also quotes from a letter by "W. C. R." in the Field about the end of 1868, which gives a very curious incident of a crocodile stealing up to a pack of otters fishing, and got within thirty yards; "but no sooner was the water broken by the hideous head of the reptile, than an otter, which evidently was stationed on the opposite bank as a sentinel, sounded the alarm by a whistling sort of sound. In an instant those in the water rushed to the bank and disappeared among the jungle, no doubt much to the disgust of the mugger."

I have not heard any one allude to the offensive glands of the Indian otter, but I remember once dissecting one and incautiously cutting into one of these glands, situated, I think, near the tail. It is now over twenty years ago, so I cannot speak with authority, but I remember the abominable smell, which quite put a stop to my researches at the time.

This otter is trained in some parts of India, in the Jessore district and Sunderbunds of Bengal, to drive fish into nets. In China a species there is driven into the water with a cord round its waist, which is hauled in when the animal has caught a fish.

NO. 196. LUTRA MONTICOLA vel SIMUNG(Jerdon's No. 101)HABITAT.—Nepal, Sumatra, and Borneo.

DESCRIPTION.—"The colour is more rufous umber-brown than L. nair, and does not exhibit any tendency to grizzling, and the under surface is only somewhat hoary, well washed with brownish; the chin and edge of the lips are whitish; and the silvery hoary on the sides of the head, on the throat, and on the under surface of the neck and of the chest is marked; the tail above and below is concolorous with the trunk. The length of the skeleton of an adult female, measured from the tip of the premaxillaries to the end of the sacral vertebræ, is 23·25, and the tail measures 17·75 inches" (Anderson). Of the Sumatran specimen the first notice was published in 1785 in the first edition of Marsden's 'History of Sumatra.' This otter is larger than the common Indian one, the skull of a female, as given by Dr. Anderson, exceeding in all points that of male of Lutra nair.

Jerdon has this as Lutra vulgaris, which is the common English otter, but there is a difference in the skull.

NO. 197. LUTRA ELLIOTIHABITAT.—Southern Mahratta country.

DESCRIPTION.—The colouring is the same as the last, only a little darker; the distribution of the silvery white is the same; the muzzle is however more depressed than in the last species, and it differs from L. nair by a broader, more arched head, and shorter muzzle.