полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

The name was given to it by the ancients on the supposition that it was a cross between the lion and the pard, from a fancied resemblance to the former on account of the mane or ruff of hair possessed by the hunting leopard. Apparently this animal must have been more familiar to our remote ancestors than the pard, for the name has been attached for centuries to the larger spotted Cats indiscriminately. I have not time just now to attempt to trace the species of the leopard which formerly graced the arms of the English kings, but I should not be surprised if it were the guepard or chita. The old representations were certainly attenuated enough; and the animal must have been familiar to the crusaders, as we know it was before them to the Romans.

Mr. Blyth, who speculated on the origin of the name, in one of his able articles on the felines of India in the India Sporting Review of April 1856, makes no allusion to the above nor to the probable confusion that may have arisen in the middle ages over the spotted Cats. Although the term leopard, as applied to panthers, has the sanction of almost immemorable custom, I do not see why, in writing on the subject, we should perpetuate the misnomer, especially as most naturalists and sportsmen are now inclined to make the proper distinction. I have always avoided the use of the term leopard, except when speaking of the hunting chita, preferring to call the others panthers.

Then again we come on disputed ground. Of panthers how many have we, and how should they be designated? I am not going farther afield than India in this discussion beyond alluding to the fact that the jaguar of Brazil is almost identical with our pard as far as marking goes, but is a stouter, shorter-tailed animal, which justifies his being classed as a species; therefore we must not take superficial colouring as a test, but class the black and common pards together; the former, which some naturalists have endeavoured to made into a separate species (Felis melas), being merely a variety of the latter. They present the same characteristics, although Jerdon states that the black is the smaller animal. They have been found in Java to inhabit the same den, according to Professor Reinwardt and M. Kuhl, and they inter-breed, as has been proved by the fact that a female black pard has produced a black and a fulvous cub at the same birth. This is noticed by Mr. Sanderson in his book, and he got the information from the director of the Zoological Society's Menagerie at Amsterdam. "Old Fogy," a constant contributor to the old India Sporting Review, a good sportsman and naturalist, with whom Blyth kept up a correspondence, wrote in October 1857 that, "in a litter of four leopard cubs one was quite black; they all died, but both the parents were of the ordinary colour and marking; they were both watched at their cave, and at last shot, one with an arrow through the heart. Near a hill village a black male leopard was often seen and known to consort with an ordinary female. I have observed them myself once, if not twice."

An observant sportsman, "Hawkeye," in one of his letters to the South of India Observer, remarks that "on one occasion a gentleman saw an old leopard accompanied by two of her offspring, one red, the other black." He also says he has never known "of two black leopards in company," but black pards have bred in zoological gardens. I am told that cubs have been born in the Calcutta Garden, but they did not live. General MacMaster, in his notes on Jerdon, makes the pertinent remark: "If however black panthers are only accidental, it is odd that no one has yet come on a black specimen of one of the larger cats, F. leo tigris." I see no reason why such should not yet be discovered; he was perhaps not aware that the jaguar of Brazil, which comes next to the tiger, has been found black (Felis nigra of Erxleben). A black tiger would be a prize. General MacMaster relates that he once watched a fine black cat basking in the sun, and noticed that in particular lights the animal exhibited most plainly the regular brindled markings of the ordinary gray wild or semi-wild cat. These markings were as black or blacker than the rest of his hair. His mother was a half-wild gray brindle.

I think we have sufficient evidence that the black pard is merely a variety of the common one, but now we come to the pards themselves, and the question as to whether there are two distinct species or two varieties; Blyth, Jerdon and other able naturalists, although fully recognizing the differences, have yet hesitated to separate them, and they still remain in the unsatisfactory relation to each other of varieties. I feel convinced in my own mind that they are sufficiently distinct to warrant their being classed, and specifically named apart. It is not as I said before, that we should go upon peculiarities of marking and colour, although these are sufficiently obvious, but on their osteology and also the question of interbreeding and production. Grant their relative sizes, one so much bigger than the other, and the difference in colour and marking, has it ever been known that out of a litter of several cubs by a female of the larger kind, one of the smaller sort has been produced, or vice versâ? This is a question that yet remains for investigation. My old district had both kinds in abundance, and I have had scores of cubs, of both sorts, brought to me—cubs which could be distinguished at a glance as to which kind they belonged to, but I never remember any mixture of the two. As regards the difference in appearance of the adults there can be no question. The one is a higher, longer animal, with smooth shiny hair of a light golden fulvous, the spots being clear and well defined, but, as is remarked by Sir Walter Elliot, the strongest difference of character is in the skulls, those of the larger pard being longer and more pointed, with a ridge running along the occiput, much developed for the attachment of the muscles, whereas the smaller pard has not only a rougher coat, the spots being more blurred, but it is comparatively a more squat built animal, with a rounder skull without the decided occipital ridge. There is a mass of evidence on the point of distinctness—Sir Walter Elliot, Horsfield, Hodgson, Sir Samuel Baker, Johnson (author of 'Field Sports in India'), "Mountaineer," a writer in the Bengal Sporting Review, even Blyth and Jerdon, all speak to the difference, and yet no decided separation has been made. There is in fact too much confusion and too many names. For the larger animal Felis pardus is appropriate, and the leopardus of Temminck, Schreber and others is not. Therefore that remains; but what is the smaller one to be called? I should say Felis panthera which, being common to Asia and Africa, was probably the panther of the Romans and Greeks. Jerdon gives as a synonym F. longicaudata (Valenciennes), but I find on examination of the skulls of various species that F. longicaudata has a complete bony orbit which places it in Gray's genus Catolynx, and it is too small for our panther. We might then say that we have the pard, the panther, and the leopard in India, and then we should be strictly correct. Some sportsmen speak of a smaller panther which Kinloch calls the third (second?) sort of panther, but this differs in no respect from the ordinary one, save in size, and it is well known that this species varies very much in this respect. I am not singular in the views I now express. Years ago Colonel Sykes, who was a well known naturalist, said of the pard: "It is a taller, stronger, and slighter built animal than the next species, which I consider the panther."

The skull of the pard in some degree resembles that of the jaguar, which again is nearest the tiger, whereas that of the panther appears to have some affinity to the restricted cats. In disposition all the pards and panthers are alike sanguinary, fierce and incapable of attachment. The tiger is tameable, the panther not so. I have had some experience of the young of both, and have seen many others in the possession of friends; and though they may, for a time, when young, be amusing pets, their innate savageness sooner or later breaks out. They are not even to be trusted with their own kind. I have known one to turn on a comrade in a cage, kill and devour him, and some of my readers may possibly remember an instance of this in the Zoological Gardens at Lahore, when, in 1868, a pard one night killed a panther which inhabited the same den, and ate a goodly portion of him before dawn. They all show more ferocity than the tiger when wounded, and a man-eating pard is far more to be dreaded than any other man-eater, as will be seen farther on from the history of one I knew.

NO. 202. FELIS PARDUSThe Pard (Jerdon's No. 105)NATIVE NAMES.—Tendua, Chita or Chita-bagh, Adnara; Hindi, Honiga; Canarese, Asnea; Mahratti, Chinna puli; Telegu, Burkal; Gondi, Bay-heera; and Tahr-hay in the Himalayas.

HABITAT.—Throughout India, Burmah, and Ceylon, and extending to the Malayan Archipelago.

DESCRIPTION.—A clean, long limbed, though compact body; hair close and short; colour pale fulvous yellow, with clearly defined spots in rosettes; the head more tiger-like than the next species; the skull is longer and more pointed, with a much developed occipital ridge.

SIZE.—Head and body from 4½ to 5½ feet; tail from 30 to 38 inches.

This is a powerful animal and very fierce as a rule, though in the case of a noted man-eater I have known it exhibit a curious mixture of ferocity and abject cowardice. It is stated to be of a more retiring disposition than the next species, but this I doubt, for I have frequently come across it in the neighbourhood of villages to which it was probably attracted by cattle. It may not have the fearlessness or impudence of the panther, which will walk through the streets of a town and seize and devour its prey in a garden surrounded by houses, as I once remember, in the case of a pony at Seonee, but it is nevertheless sufficiently bold to hang about the outskirts of villages. Those who have seen this animal once would never afterwards confuse it with what I would call the panther. There is a sleekness about it quite foreign to the other, and a brilliancy of skin with a distinctness of spots which the longer, looser hair does not admit of. But with all these external differences I am aware that there will be objection to classifying it as a separate species, unless the osteological divergences can be satisfactorily determined, and for this purpose it would be necessary to examine a large series of authenticated skulls of the two kinds.

The concurrence of evidence as to the habits of this species is that it is chiefly found in hilly jungles preying on wild animals, wild pigs, and monkeys, but not unfrequently, as I know, haunting the outskirts of villages for the sake of stray ponies and cattle. The largest pard I have ever seen was shot by one of my own shikaris in the act of stalking a pony near a village. I was mahseer-fishing close by at the time, and had sent on the man, a little before dusk, to a village a few miles off, to arrange for beating up a tiger early next day. Jerdon says this is the kind most common in Bengal, but he does not say in what parts of Bengal, and on what authority. I have no doubt it abounds in Sontalia and Assam, and many other hilly parts. At Colgong, Mr. Barnes informed him that many cases of human beings killed by pards were known in the Bhaugulpore district. At Seonee we had one which devastated a tract of country extending to about 18 miles in diameter. He began his work in 1857 by carrying off a follower of the Thakur of Gurwarra, on whom we were keeping a watch during the troublous times of the mutiny. My brother-in-law, Colonel Thomson and I, went after him under the supposition that it was a tiger that had killed the man, and it was not till we found the body at the bottom of a rocky ravine that we discovered it was a pard. During the beat he came out before us, went on, and was turned back by an elephant and came out again a third time before us; but we refrained from firing as we expected a man-eating tiger. I left Seonee for two years to join the Irregular Corps to which I had been posted, and after the end of the campaign, returned again to district work, and found that the most dreaded man-eater in the district was the pard whose life we had spared. There was a curious legend in connection with him, like the superstitious stories of Wehr wolves in Northern Europe. I have dealt fully with it in "Seonee," and Forsyth has also given a version of it in the 'Highlands of Central India,' as he came to the district soon after the animal was destroyed. Some of the aborigines of the Satpura Range are reputed to have the power of changing themselves into animals at will, and back again into the human form. The story runs, that one day one of these men, accompanied by his wife, came to a glade in the jungle where some nilgai were feeding. The woman expressed a wish for some meat, on which the husband gave her a root to hold, and to give him to smell on his return. He changed himself into a pard, killed one of the nilgai, and came bounding back for the root; but the terrified woman lost her nerve, flung away the charm, and rushed from the place. The husband hunted about wildly for the root, but in vain; and then inflamed with rage he pursued her, and tore her to pieces and continued to wreak his vengeance on the human race. Such was the history of the man-eating panther of Kahani, as related in the popular traditions of the country, and certainly everything in the career of this extraordinary animal tended to foster the unearthly reputation he had gained. Ranging over a circle, the radius of which may be put at eighteen miles, no one knew when and where he might be found. He seemed to kill for killing's sake, for often his victims—at times three in a single night—would be found untouched, save for the fatal wound in the throat. The watcher on the high machaun, the sleeper on his cot in the midst of a populous village, were alike his prey. The country was demoralized; the bravest hunters refused to go after him; wild pigs and deer ravaged the fields; none would dare to watch the growing crops. If it had been an ordinary panther who would have cared? Had not each village its Shikari? men who could boast of many an encounter with tiger and bear, and would they shrink from following up a mere animal? Certainly not; but they knew the tradition of Chinta Gond, and they believed it. What could they do?

On the morning of the second day, after leaving Amodagurh, the two sportsmen neared Sulema, a little village not far from Kahani, out of which it was reported the panther had taken no less than forty people within three years. There was not a house that had not mourned the loss of father, or mother, or brother, or sister, or wife or child, from within this little hamlet. Piteous indeed were the tales told as our friends halted to gather news, and the scars of the few who were fortunate enough to have escaped with life after a struggle with the enemy, were looked at with interest; but the most touching of all were the stories artlessly told by a couple of children, one of whom witnessed the death of a sister, and the other of a brother, both carried off in broad daylight, for the fell destroyer went boldly to work, knowing that they were but weak opponents."13 I was out several times after this diabolical creature, but without success; as I sat out night after night I could hear the villagers calling from house to house hourly, "Jágté ho bhiya! jágté ho!" "Are you awake, brothers? are you awake!" All day long I scoured the country with my elephant, all night long I watched and waited. My camp was guarded by great fires, my servants and followers were made to sleep inside tents, whilst sentries with musket and bayonet were placed at the doors; but all to no purpose. The heated imagination of one sentry saw him glowering at him across the blazing fire. A frantic camp-follower spoilt my breakfast next morning ere I had taken a second mouthful, by declaring he saw him in an adjoining field. Then would come in a tale of a victim five miles off during the night, and then another, and sometimes a third. I have alluded before to his cowardice; in many cases a single man or boy would frighten him from his prey. On one occasion, in my rounds after him, I came upon a poor woman bitterly crying in a field; beside her lay the dead body of her husband. He had been seized by the throat and dragged across the fire made at the entrance of their little wigwam in which they had spent the night, watching their crops. The woman caught hold of her husband's legs, and, exerting her strength against the man-eater's, shrieked aloud. He dropped the body and fled, making no attempt to molest her or her little child of about four years of age. This man was the third he had attacked that night.

He was at last killed, by accident, by a native shikari who, in the dusk, took him for a pig or some such animal, and made a lucky shot; but the tale of his victims had swelled over two hundred during the three years of his reign of terror.

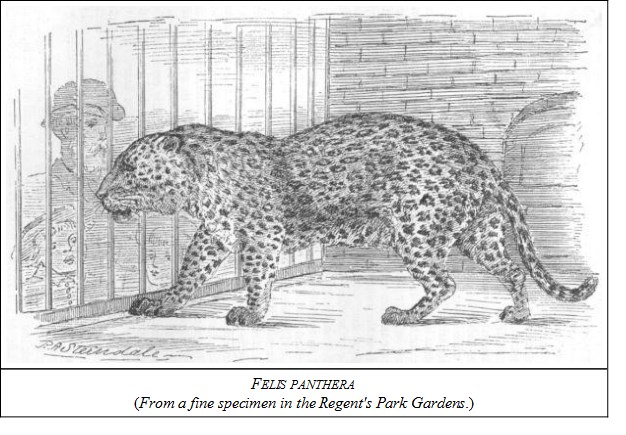

NO. 203. FELIS PANTHERAThe PantherNATIVE NAMES.—Chita, Gorbacha, Hindi; Beebeea-bagh, Mahrathi; Bibla, of the Chita-catchers; Ghur-hay or Dheer-hay of the hill tribes; Kerkal, Canarese.

HABITAT.—India generally, Burmah and Ceylon, extending also into the Malayan countries.

DESCRIPTION.—Much smaller than the last, with comparatively shorter legs and rounder head; the fur is less bright; the ground-work often darker in colour, and the rosettes are more indistinct which is caused by the longer hairs intermingling and breaking into the edges of the spots; tail long and furry at the end. According to Temminck the tail is longer than that of the last species, having 28 caudal vertebræ against 22 of the other; if this be found to be the normal state, there will be additional grounds for separating the two.

SIZE.—Head and body, 3 to 3½ feet; tail, 2½ feet; height from 1½ to 2 feet.

This animal is more common than the pard, and it is more impudent in venturing into inhabited places. This is fortunate, for it is seldom a man-eater, although perhaps children may occasionally be carried off. I have before mentioned one which killed and partially devoured a pony in the heart of a populous town, and many are the instances of dogs being carried off out of the verandahs of Europeans' houses. A friend of mine one night being awoke by a piteous howl from a dog, chained to the centre pole of his tent, saw the head and shoulders of one peering in at the door; it retreated but had the audacity to return in a few minutes. Jerdon and other writers have adduced similar instances. It is this bold and reckless disposition which renders it easier to trap and shoot. The tiger is suspicious to a degree, and always apprehensive of a snare, but the panther never seems to trouble his head about the matter, but walks into a trap or resumes his feast on a previously killed carcase, though it may have been moved and handled. There is another thing, too, which shows the different nature of the beast. There is little difficulty in shooting a panther on a dark night. All that is necessary is to suspend, some little distance off, a common earthen gharra or water pot, with an oil light inside, the mouth covered lightly with a sod, and a small hole knocked in the side in such a way as to allow a ray of light to fall on the carcase. No tiger would come near such an arrangement, but the panther boldly sets to his dinner without suspicion, probably from his familiarity with the lights in the huts of villages.

I may here digress a little on the subject of night shooting. Every one who has tried it knows the extreme difficulty in seeing the sights of the rifle in a dark night. The common native method is to attach a fluff of cotton wool. On a moonlight night a bit of wax, with powdered mica scattered on it, will sometimes answer. I have seen diamond sights suggested, but all are practically useless. My plan was to carry a small phial of phosphorescent oil, about one grain to a drachm of oil dissolved in a bath of warm water. A small dab of this, applied to the fore and hind sights, will produce two luminous spots which will glow for about 40 or 50 seconds or a minute.

Dr. Sal Müller says of this species that it is occasionally found sleeping stretched across the forked branch of a tree, which is not the case with either the tiger or the pard. According to Sir Stamford Raffles, the Rimau-dahan or clouded panther (miscalled tiger) Felis macrocelis, has the same habit.

I would remark in conclusion that in the attempt to define clearly the position of these two animals the following points should be investigated by all who are interested in the subject and have the opportunity.

First the characteristics of the skull:—

viz.—Length, and breadth as compared with length of each, with presence or absence of the occipital ridge.

2ndly.—Number of caudal vertebræ in the tails of each.

3rdly.—Whether in a litter, from one female, cubs of each sort have been found.

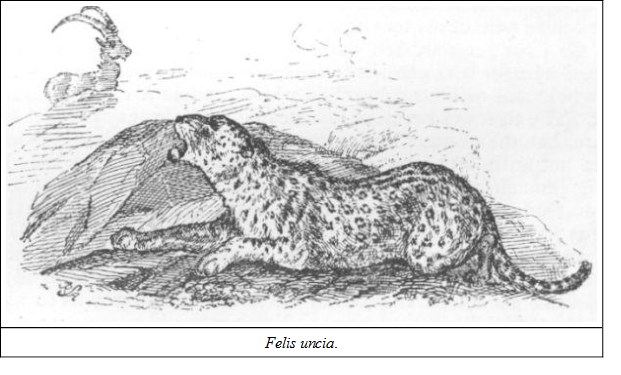

NO. 204. FELIS UNCIAThe Ounce or Snow Panther (Jerdon's No. 106)NATIVE NAMES.—Iker, Tibetan; Sah, Bhotia; Phalé, Lepcha; Burrel-hay, Simla hillmen; Thurwag in Kunawur. The Snow-Leopard of European sportsmen.

HABITAT.—Throughout the Himalayas, and the highland regions of Central Asia.

DESCRIPTION.—Pale yellowish or whitish isabelline, with small spots on the head and neck, but large blotchy rings and crescents, irregularly dispersed on the shoulders, sides and haunches; from middle of back to root of tail a medium irregular dark band closely bordered by a chain of oblong rings; lower parts dingy white, with some few dark spots about middle of abdomen; limbs with small spots; ears externally black; tail bushy with broad black rings.

SIZE.—Head and body about 4 feet 4 inches; tail, 3 feet; height, about 2 feet.

I have only seen skins of this animal, which is said to frequent rocky ground, and to kill Barhel, Thar, sheep, goats, and dogs, but not to molest man. This species is distinguishable from all the preceding felines by the shortness and breadth of the face and the sudden elevation of the forehead—Gray. Pupil round—Hodgson.

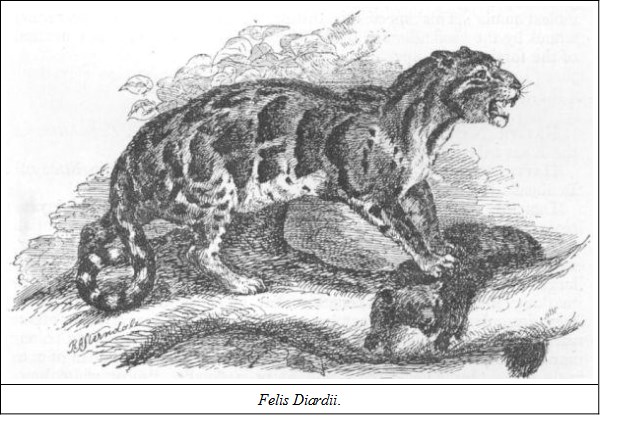

NO. 205. FELIS DIARDII vel MACROCELISThe Clouded Panther (Jerdon's No. 107)NATIVE NAMES.—Tungmar, Lepcha; Zik, Bhotia; Lamchitta, of the Khas tribe (Jerdon). Rimau dahan of Sumatra.

HABITAT.—Nepal, Sikim, Assam, Burmah, and down the Malayan Peninsula to Sumatra, Java and Borneo.

DESCRIPTION.—A short-legged long-bodied animal, with a very elongated skull; the upper canines are the longest in comparison of all living felines, and in this respect it comes nearest to the extinct species Felis smilodon. The ground-work of the colouring is a pale buff, with large, irregular, cloud-like patches of black. Blyth remarks that the markings are exceedingly beautiful, but most difficult to describe, as they not only vary in different specimens, but also in the two sides of one individual. Jerdon's description is as follows: "Ground colour variable, usually pale greenish brown or dull clay brown, changing to pale tawny on the lower parts, and limbs internally, almost white however in some. In many specimens the fulvous or tawny hue is the prevalent one; a double line of small chain-like stripes from the ears, diverging on the nape to give room to an inner and smaller series; large irregular clouded spots or patches on the back and sides edged very dark and crowded together; loins, sides of belly and belly marked with irregular small patches and spots; some black lines on the cheeks and sides of neck, and a black band across the throat; tail with dark rings, thickly furred, long; limbs bulky, and body heavy and stout; claws very powerful." Hodgson stated that the pupil of the eye is round, but Mr. Bartlett, whose opportunities of observation have been much more frequent, is positive that it is oval.