полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

But not yet firm and impregnable were the bulwarks of Christianity. |A.D. 360.|While dreaming anchorites in the deserts of Thebais were repeating the results of fasting and insanity as the manifestation of divine favour, the world was startled from its security by the appalling discovery that the emperor himself, the young and vigorous Julian, was a follower of the old philosophers, and a worshipper of the ancient gods. And a dangerous antagonist he was, even independent of his temporal power. His personal character was irreproachable, his learning and talent beyond dispute, and his eloquence and dialectic skill sharpened and improved by an education in Athens itself. Less than forty years had elapsed since Constantine pronounced the sentence of banishment on the heathen deities. It was not possible that the Christian truth was in every instance received where the old falsehood was driven away. We may therefore conclude, without the aid of historic evidence, that there must have been innumerable districts—villages in far-off valleys, hidden places up among the hills—where the name of Christ had not yet penetrated, and all that was known was, that the shrine of the local gods was overthrown, and the priests of the old ceremonial proscribed. When we remember that the heathen worship entered into almost all the changes of the social and family life—that its sanction was necessary at the wedding—that its auguries were indispensable at births—that it crowned the statue of the household god with flowers—that it kept alive the fire upon the altar of the emperor—and that it was the guardian of the tombs of the departed, as it had been the principal consolation during the funeral rites,—we shall perceive that, irrespective of absolute faith in his system of belief, the cessation of the priest’s office must have been a serious calamity. The heathen establishment had been enriched by the piety or ostentation of many generations. There must have been still alive many who had been turned out of their comfortable temples, many who viewed the assumption of Christianity into the State as a political engine to strengthen the tyranny under which the nations groaned. We may see that self-interest and patriotism may easily have been combined in the effort made by the old faith to regain the supremacy it had lost. The Emperor Julian endeavoured to lift up the fallen gods. He persecuted the Christians, not with fire and sword, but with contempt. He scorned and tolerated. He preached moderation, self-denial, and purity of life, and practised all these virtues to an extent unknown upon a throne, and even then unusual in a bishop’s palace.

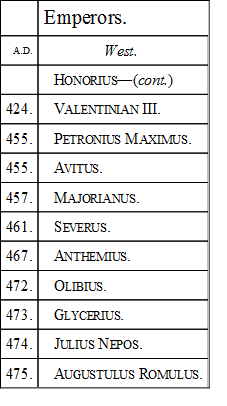

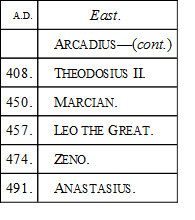

How those Christian graces, giving a charm and dignity to the apostate emperor, must have received a still higher authority from the painful contrast they presented to the agitated condition and corrupted morals of the Christian Church! Everywhere there was war and treachery, and ambition and unbelief. Half the great sees were held by Arians, who raved against the orthodox; and the other half were held by Athanasius and his followers, who accused their adversaries of being “more cruel than the Scythians, and more irreconcilable than tigers.” At Rome itself there was an orthodox bishop and an Arian rival. It is not surprising that Julian, disgusted with the scenes presented to him by the mutual rage of the Christian sects, thought the surest method of restoring unity to the empire would be to silence all the contending parties and reintroduce the peaceful pageantries of the old Pantheon. If some of the fanciful annotators of the new faith had allegorized the facts of Christianity till they ceased to be facts at all, Julian performed the same office for the heathen gods. Jupiter and the rest were embodiments of the hidden powers of nature. Vulcan was the personification of human skill, and Venus the beautiful representative of connubial affection. But men’s minds were now too sharpened with the contact they had had with the real to be satisfied with such fallacies as these. Eloquent teachers arose, who separated the eternal truths of revelation from the accessories with which they were temporarily combined. Ridicule was retorted on the emperor, who had sneered at the Christian services. Who, indeed, who had caught the slightest view of the spirituality of Christ’s kingdom, could abstain from laughing at the laborious heathenism of the master of the world? He cut the wood for sacrifice, he slew the goat or bull, and, falling down on his knees, puffed with distended cheeks the sacred fire. He marched to the temple of Venus between two rows of dissolute and drunken worshippers, striving in vain by face and attitude to repress the shouts of riotous exultation and the jeers of the spectators. Then, wherever he went he was surrounded by pythonesses, and augurs, and fortune-tellers, magicians who could work miracles, and necromancers who could raise the dead. When he restored a statue to its ancient niche, he was rewarded by a shake of its head; when he hung up a picture of Thetis or Amphitrite, she winked in sign of satisfaction. Where miracles are not believed, the performance of them is fatal. But his expenditure of money in honouring the gods was more real, and had clearer results. He nearly exhausted the empire by the number of beasts he slew. He sent enormous offerings to the shrines of Dodona, and Delos, and Delphi. He rebuilt the temples, which time or Christian hatred had destroyed; and, by way of giving life to his new polity, he condescended to imitate the sect be despised, in its form of worship, in its advocacy of charity, peace, and good will, and in its institutions of celibacy and retirement, which, indeed, had been a portion of heathen virtue before it was admitted into the Christian Church. But his affected contempt soon degenerated into persecution. He would have no soldiers who did not serve his gods. Many resigned their swords. He called the Christians “Galileans,” and robbed them of their property and despitefully used them, to try the sincerity of their faith. “Does not your law command you,” he said, “to submit to injury, and to renounce your worldly goods? Well, I take possession of your riches that your march to heaven may be unencumbered.” All moderation was now thrown off on both sides. Resistance was made by the Christians, and extermination threatened by the emperor. In the midst of these contentions he was called eastward to resist the aggression of Sapor, the Persian king. An arrow stretched Julian on his couch. He called round him his chief philosophers and priests. With them, in imitation of Socrates, he entered into deep discussions about the soul. |A.D. 363.|Nothing more heroic than his end, or more eloquent than his parting discourse. But death did not soften the animosity of his foes. The Christians boasted that the arrow was sent by an angel, that visions had foretold the persecutor’s fall, and that so would perish all the enemies of God. The adherents of the emperor in return blamed the Galileans as his assassins, and boldly pointed to Athanasius, the leader of the Christians, as the culprit. Athanasius would certainly not have scrupled to rid the world of such an Agag and Holofernes, but it is more probable that the death occurred without either a miracle or a murder. The successors of Julian were enemies of the apostate. They speedily restored their fellow-believers to the supremacy they had lost. A ferocious hymn of exultation by Gregory of Nazianzen was chanted far and wide. Cries of joy and execration resounded in market-places, and churches, and theatres. The market-places had been closed against the Christians, their churches had been interdicted, and the theatres shut up, by the overstrained asceticism of the deceased. It was perceived that Christianity had taken deeper root than the apostate had believed, and henceforth no effort could be made to revivify the old superstition. After a nominal election of Jovian, the choice of the soldiers fell on two of their favourite leaders, Valentinian and Valens, brothers, and sufferers in the late persecutions for their faith. Named emperors of the Roman world, they came to an amicable division of the empire into East and West. Valens remained in Constantinople to guard the frontiers of the Danube and the Euphrates; while Valentinian, who saw great clouds darkening over Italy and Gaul, fixed his imperial residence in the strong city of Milan. The separation took place in 364, and henceforth the stream of history flows in two distinct and gradually diverging channels. This century has already been marked by the removal of the seat of power to Constantinople; by the attempt at the restoration of Paganism by Julian; and we have now to dwell for a little on the third and greatest incident of all, the invasion of the Goths, and final settlement of hostile warriors on the Roman soil.

Names that have retained their sound and established themselves as household words in Europe now meet as at every turn. Valentinian is engaged in resisting the Saxons. The Britons, the Scots, the Germans, are pushing their claims to independence; and in the farther East, the persecutions and tyranny of the contemptible Valens are suddenly suspended by the news that a people hitherto unheard of had made their appearance within an easy march of the boundary, and that universal terror had taken possession of the soldiers of the empire. Who were those soldiers? We have seen for many years that the policy of the emperors had been to introduce the barbarians into the military service of the State, and to expose the wasted and helpless inhabitants to the rapacity of their tax-gatherers. This system had been carried to such a pitch, that it is probable there were none but mercenaries of the most varying interests in the Roman ranks. Yet such is the effect of discipline, and the pride of military combination, that all other feelings gave way before it. The Gothic chief, now invested with command in the Roman armies, turned his arms against his countrymen. The Albanian, the Saxon, the Briton, elevated to the rank of duke or count, looked back on Marius and Cæsar as their lineal predecessors in opposing and conquering the enemies of Rome. The names of the generals and magistrates, accordingly, which we encounter after this date, have a strangely barbaric sound. There are Ricimer, and Marcomir, and Arbogast—and finally, the name which overtopped and outlived them all, the name of Alaric the Goth. Now, the Goths, we have seen, had been settled for many generations on the northern side of the Danube. Much intercourse must have taken place between the inhabitants of the two banks. There must have been trade, and love, and quarrellings, and rejoicings. At shorter and shorter intervals the bravest of the tribes must have passed over into the Roman territory and joined the Legions. Occasionally a timid or despotic emperor would suddenly order his armies across, and carry fire and sword into the unsuspecting country. But on the whole, the terms on which they lived were not hostile, for the ties which united the two peoples were numerous and strong. Even the languages in the course of time must have come to be mutually intelligible, and we read of Gothic leaders who were excellent judges of Homer and seldom travelled without a few chosen books. This being the case, what was the consternation of the almost civilized Goths in the fertile levels of the present Wallachia and Moldavia to hear that an innumerable horde of dreadful savages, calling themselves Huns and Magyars, had appeared on the western shore of the Black Sea, and spread over the land, destroying, murdering, burning whatever lay in their way! Cooped up for an unknown period, it appeared, on the northeastern side of the Palus Mæotis, now better known to us as the Sea of Azof—living on fish out of the Don, and on the cattle of the long steppes which extend across the Volga, these sons of the Scythian desert had never been heard of either by the Goths or Romans. A hideous people to behold, as the perverted imagination of poet or painter could produce. They were low in stature, but broad-shouldered and strong. Their wide cheek-bones and small eyes gave them a savage and cruel expression, which was increased by their want of nose, for the only visible appearance of that indispensable organ consisted of two holes sunk into the square expanse of their faces. Fear is not a flattering painter, but from these rude descriptions it is easy to recognise the Calmuck countenance; and when we add their small horses, long spears, and prodigious lightness and activity, we shall see a very close resemblance between them and their successors in the same district, the Russian Cossacks of the Don. On, on, came the torrent of these pitiless, fearless, ugly, dirty, irresistible foes. The Goths, terrified at their aspect, and bewildered with the accounts they heard of their numbers and mode of warfare, petitioned the emperor to give them an asylum on the Roman side. Their prayer was granted on condition of depositing their children and arms in Roman hands. They had no time to squabble about terms. Every thing was agreed to. Boats manned by Roman soldiers were busy, day and night in transporting the Gothic exiles to the Roman side. Arms and jewels, and wives and children, the furniture of their tents, and idols of their gods, all got safely across the guarding river. The Huns, the Alans, and the other unsightly hordes who had gathered in the pursuit, came down to the bank, and shouted useless defiance and threats of vengeance. The broad Danube rolled between; and there rested that night on the Roman soil a whole nation, different in interest, in manners and religion, from the population they had joined, numbering upwards of a million souls, bound together by every thing that constitutes the unity of a people. The avarice and injustice of the Roman authorities negatived the clause of the agreement that stipulated for the surrender of the Gothic arms. To redeem their swords and spears, they parted with the silver and gold they had amassed in their predatory incursions on the Roman territory. They know that once in possession of their weapons they could soon reclaim all they gave—and in no long time the attempt was made. Fritigern, the leader of their name, led them against the armies of Rome. Insulted at their audacity, the Emperor Valens, at the head of three hundred thousand men, met them in the plain of Adrianople. The existence of the Gothic people was at stake. |A.D. 379.|They fought with desperation and hatred. The emperor was defeated, leaving two-thirds of his army on the field of battle. Seeking safety in a cottage at the side of the road, he was burned by the inexorable pursuers, who, gathering up their broken lines, marched steadily through the intervening levels and gazed with enraptured eyes on the glittering towers and pinnacles of Constantinople itself. But the walls were high and strongly armed. The barbarians were inveigled into a negotiation, and mastered by the unequal powers of lying at all times characteristic of the Greeks. Fritigern consented to withdraw his troops: some were embodied in the levies of the empire, and others dispersed in different provinces. Those settled in Thrace were faithful to their employers, and resisted their ancient enemies the Huns; but the great body of the discontented conquerors were ready for fresh assaults on the Roman land. Theodosius, called to the throne in 379, succeeded in staving off the evil day; but when the final partition of the empire took place between his two sons—Honorius and Arcadius—there was nothing to oppose the terrible onset of the Goths. |A.D. 394.|At their head was Alaric, the descendant of their original chiefs, and himself the bravest of his warriors. He broke into Greece, forcing his way through Thermopylæ, and devastated the native seats of poetry and the arts with fire and sword. The ruler at Constantinople heard of his advance with terror, and opposed to him the Vandal Stilicho, the greatest of his generals. But the wily Alaric declined to fight, and out-manœuvred his enemies, escaping to the sure fastnesses of Epirus, and sat down sullen and discontented, meditating further expeditions into richer plains, and already seeing before him the prostrate cities of Italy. The terror of Arcadius tried in vain to soften his rage, or satisfy his ambition with vain titles, among others, that of Count of the Illyrian Border. The spirit of aggression was fairly roused. All the Gothic settlers in the Roman territory were ready to join their countrymen in one great and combined attack;—and with this position of the personages of the drama, the curtain falls on the fourth century, while preparations for the great catastrophe are going on.

FIFTH CENTURY

Chrysostom, Jerome, Augustine, Pelagius, (405,) Sidonius Apollinaris, Patricius, Macrobius, Vicentius of Lerins, (died 450,) Cyril, Bishop of Alexandria, (412-444.)

THE FIFTH CENTURY

END OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE – FORMATION OF MODERN STATES – GROWTH OF ECCLESIASTICAL AUTHORITYWe find the same actors on the stage when the curtain rises again, but circumstances have greatly changed. After his escape from Stilicho, Alaric had been “lifted on the shield,” the wild and picturesque way in which the warlike Goths nominated their kings, and henceforth was considered the monarch of a separate and independent people, no longer the mere leader of a band of predatory barbarians. In this new character he entered into treaties with the emperors of Constantinople or Rome, and broke them, as if he had already been the sovereign of a civilized state.

In 403 he broke up from his secure retreat on the Adriatic, and burst into Italy, spreading fire and famine wherever he went. Honorius, the Emperor of the West, fled from Milan, and was besieged in Asti by the Goths. Here would have ended the imperial dynasty, some years before its time, if it had not been for the watchful Stilicho. This Vandal chief flew to the rescue of Honorius, repulsed Alaric with great slaughter, and delivered his master from his dangerous position. The grateful emperor entered Rome in triumph, and for the last time the Circus streamed with the blood of beasts and men. |A.D. 408.|He retired after this display to the inaccessible marshes of Ravenna, at the mouths of the Po, and, secure in that fortress, sent an order to have his preserver and benefactor murdered; Stilicho, the only hope of Rome, was assassinated, and Alaric once more saw all Italy within his grasp. It was not only the Goths who followed Alaric’s command. All the barbarians, of whatever name or race, who had been transplanted either as slaves or soldiers—Alans, Franks, and Germans—rallied round the advancing king, for the impolitic Honorius had issued an order for the extermination of all the tribes. There were Britons, and Saxons, and Suabians. It was an insurrection of all the manly elements of society against the indescribable depravation of the inhabitants of the Peninsula. The wildest barbarian blushed in the midst of his ignorance and rudeness to hear of the manners of the highest and most distinguished families in Rome. Nobody could hold out a hand to avert the judgment that was about to fall on the devoted city. Ambassadors indeed appeared, and bought a short delay at the price of many thousand pounds’ weight of gold and silver, and of large quantities of silk; but these were only additional incitements to the cupidity of the invader. Tribe after tribe rose up with fresh fury; warriors of every hue and shape, and with every manner of equipment. The handsome Goth in his iron cuirass; the Alan with his saddle covered with human skin; the German making a hideous sound by shrieking on the sharp edge of his shield; and the countryman of Alaric himself sounding the “horn of battle,” which terrified the Romans with its ominous note—all started forward on the march. At the head of each detachment rode a band, singing songs of exultation and defiance; and the Romans, stupefied with fear, saw these innumerable swarms defile towards the Milvian bridge and close up every access to the town. There was no corn from Sicily or Africa; a pest raged in every house, and hunger reduced the inhabitants to despair. The gates were thrown open, and all the pent-up animosity of the desert was poured out upon the mistress and corrupter of the world. For six days the city was given up to remorseless slaughter and universal pillage. The wealth was incalculable. The captives were sold as slaves. The palaces were overthrown, and the river choked with carcasses and the treasures of art which the barbarians could not appreciate. “The new Babylon,” cries Bossuet, the great Bishop of Meaux, “rival of the old, swelled out like her with her successes, and, triumphing in her pleasures and riches, encountered as great a fall.” And no man lamented her fate.

|A.D. 410.|

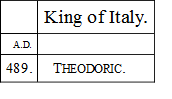

Alaric, who had thus achieved a victory denied to Hannibal and Pyrrhus, resolved to push his conquests to the end of Italy. But on his march towards the Straits of Sicily, illness overtook him. His life had been unlike that of other men, and his burial was to excite the wonder of the Bruttians, among whom he died. A large river was turned from its course, and in its channel a deep grave was dug and ornamented with monumental stone. To this the body of the barbaric king was carried, clothed in full armour, and accompanied with some of the richest spoils of Rome; and then the stream was turned on again, the prisoners who had executed the works were slaughtered to conceal the secret of the tomb, and nobody has ever found out where the Gothic king reposes. But while the Busentino flowed peaceably on, and guarded the body of the conqueror from the revenge of the Romans, new perils were gathering round the throne of the Western emperor. As if the duration of the empire had been inseparably connected with the capital, the reverence of mankind was never bestowed on Milan or Ravenna, in which the court was now established, as it had been upon Rome. Britain had already thrown off the distant yoke, and submitted to the Saxon invaders. Spain had also peaceably accepted the rule of the three kindred tribes of Sueves and Alans and Vandals. Gaul itself had given its adhesion to the Burgundians (who fixed their seat in the district which still bears their name) and offered a feeble resistance to any fresh invader. Ataulf, the brother of Alaric, came to the rescue of the empire, and of course completed the destruction. He married the sister of Honorius, and retained her as a hostage of the emperor’s good faith. He promised to restore the revolted provinces to their former master, and succeeded in overthrowing some competitors who had started up to dispute with Ravenna the wrecks of former power. He then forced his way into Spain, and the hopes of the degenerate Romans were high. But murder, as usual, stopped the career of Ataulf, and all was changed. |A.D. 415.|The emperor ratified the possessions which he could not dispute, and in the first twenty years of this century three separate kingdoms were established in Europe. This was soon followed by a Vandal conquest of the shores of Africa, which raised Carthage once more to commercial importance, united Sicily, Corsica, and Sardinia to the new-founded state, and by the creation of a fleet gained the command of the Mediterranean Sea, and threatened Constantinople itself.

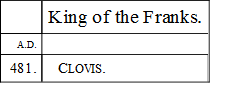

With so many provinces not only torn from the empire, but erected into hostile kingdoms, nothing was wanting but some new irruption into the still dependent territories to put a final end to the Roman name. And a new incursion came. In the very involved relations existing between the emperors of the East and West, it is difficult to follow the course of events with any clearness. While the deluded populace of Constantinople were rejoicing in the fall of their Italian rival, they heard with amazement, in 441, that a savage potentate, who had pitched his tents in the plains of Pannonia and Thrace, and kept round him, for defence or conquest, seven hundred thousand of those hideous-featured Huns who had spread devastation and terror all over the populations of Asia, from the borders of China to the Don, had determined on stretching his conquests over the whole world, and merely hesitated with which of the doomed empires to begin his career. His name was Attila, or, according to its native pronunciation, Etzel; and it soon resounded, louder and more terrifying than that of Alaric the Goth. The Emperor of the East sent an embassy to this dreadful neighbour, a minute account of which remains, and from which we learn the barbaric pomp and ceremony of the leader of the Huns, and the perfidy and debasement of the Greeks. An attempt was made to poison the redoubtable chief, and he complained of the guilty ambassador to the very person who had given him his instructions for the deed. Unsatisfied with the result, the Hunnish monarch advanced his camp. Constantinople, anxious to ward off the blow from itself, descanted to the savage king on the exposed condition and ill-defended wealth of the Italian towns. Treachery of another kind came to his aid. An offended sister of the emperor sent to Attila her ring as a mark of espousal, and he now claimed a portion of the empire as the dowry of his bride. When this was refused, he reiterated his old claim of satisfaction for the attempt upon his life, and ravaged the fields of Belgium and Gaul, in the double character of avenger of an insult and claimant of an inheritance. It does not much matter under what plea a barbarous chieftain, with six hundred thousand warriors, makes a demand. It must be answered sword in hand, or on the knees. The newly-established Frankish and Burgundian kings gathered their forces in defence of their Christian faith and their recently-acquired dominions. Attila retired from Orleans, of which he had commenced the siege, and chose for the battle-field, which was to decide the destiny of the world, a vast plain not far from Châlons, on the Marne, where his cavalry would have room to act, and waited the assault of all the forces that France and Italy could collect. The Visigoths prepared for the decisive engagement under their king, Theodoric; the Franks of the Saal under Meroveg; the Ripuarian Franks, the Saxons, and the Burgundians were under leaders of their own. |A.D. 451.|It was a fight in which were brought face to face the two conquering races of the world, and upon its result it depended whether Europe was to be ruled by a dynasty of Calmucks or left to her free progress under her Gothic and Teutonic kings. Three hundred thousand corpses marked the severity of the struggle, but victory rested with the West. Attila retreated from Gaul, and wreaked his vengeance on the Italian cities. He destroyed Aquileia, whose terrified inhabitants hid themselves in the marshes and lagoons which afterwards bore the palaces of Venice; Vicenza, Padua, and Verona were spoiled and burned. Pavia and Milan submitted without resistance. On approaching Rome, the venerable bishop, Saint Leo, met the devastating Hun, and by the gravity of his appearance, the ransom he offered, and perhaps the mystic dignity which still rested upon the city whose cause he pleaded, prevailed on him to retire. Shortly after, the chief of this brief and terrible visitation died in his tent on the banks of the Danube, and left no lasting memorial of his irruption except the depopulation his cruelty had caused, and the ruin he had spread over some of the fairest regions of the earth.