полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

Three or four more fantastic figures, “which the likeness of a kingly crown have on,” pass before our eyes, and at last we observe the powerful and substantial form of Diocletian, and feel once more we have to do with a real man. |A.D. 284.|A Druidess, we are told, had prophesied that he should attain his highest wish if he killed a wild boar. In all his hunting expeditions he was constantly on the look-out, spear in hand, for an encounter with the long-tusked monster. Unluckily for a man who had offended Diocletian before, and who had basely murdered his predecessor, his name was Aper; and unluckily, also, aper is Latin for a boar. This fact will perhaps be thought to account for the prophecy. It accounts, at all events, for its fulfilment; for, the wretched Aper being led before the throne, Diocletian descended the steps and plunged a dagger into his chest, exclaiming, “I have killed the wild boar of the prediction.” This is a painful example of how unlucky it is to have a name that can be punned upon. Determined to secure the support of what he thought the strongest body in the State, he gratified the priests by the severest of all the many persecutions to which the Christians had been exposed. By way of further showing his adhesion to the old faith, he solemnly assumed the name of Jove, and bestowed on his partner on the throne the inferior title of Hercules. In spite of these truculent and absurd proceedings, Diocletian was not altogether destitute of the softer feelings. The friend he associated with him on the throne—dividing the empire between them as too large a burden for one to sustain—was called Maximian. They had both originally been slaves, and had neither of them received a liberal education. Yet they protected the arts, they encouraged literature, and were the patrons of modest merit wherever it could be found. They each adopted a Cæsar, or lieutenant of the empire, and hoped that, by a legal division of duties among four, the ambition of their generals would be prevented. But the limits of the empire were too extended even for the vigilance of them all. In Britain, Carausius raised the standard of revolt, giving it the noble name of national independence; and, with the instinctive wisdom which has been the safeguard of our island ever since, he rested his whole chance of success upon his fleet. Invasion was rendered impossible by the care with which he guarded the shore, and it is not inconceivable that even at that early time the maritime career of Britain might have been begun and maintained, if treason, as usual, had not cut short the efforts of Carausius, who was soon after murdered by his friend Allectus. The subdivision of the empire was a successful experiment as regarded its external safety, but within, it was the cause of bitter complaining. There were four sumptuous courts to be maintained, and four imperial armies to be paid. Taxes rose, and allegiance waxed cold. The Cæsars were young, and looked probably with an evil eye on the two old men who stood between them and the name of emperor. However it may be, after many victories and much domestic trouble, Diocletian resolved to lay aside the burden of empire and retire into private life. His colleague Maximian felt, or affected to feel, the same distaste for power, and on the same day they quitted the purple; one at Nicomedia, the other at Milan. Diocletian retired to Salona, a town in his native Dalmatia, and occupied himself with rural pursuits. He was asked after a while to reassume his authority, but he said to the persons who made him the request, “I wish you would come to Salona and see the cabbages I have planted with my own hands, and after that you would never wish me to remount the throne.”

The characteristic of this century is its utter confusion and want of order. There was no longer the unity even of despotism at Rome to make a common centre round which every thing revolved. There were tyrants and competitors for power in every quarter of the empire—no settled authority, no government or security, left. In the midst of this relaxation of every rule of life, grew surely, but unobserved, the Christian Church, which drew strength from the very helplessness of the civil state, and was forced, in self-defence, to establish a regular organization in order to extend to its members the inestimable benefits of regularity and law. Under many of the emperors Christianity was proscribed; its disciples were put to excruciating deaths, and their property confiscated; but at that very time its inner development increased and strengthened. The community appointed its teachers, its deacons, its office-bearers of every kind; it supported them in their endeavours—it yielded to their directions; and in time a certain amount of authority was considered to be inherent in the office of pastor, which extended beyond the mere expounding of the gospel or administration of the sacraments. The chief pastor became the guide, perhaps the judge, of the whole flock. While it is absurd, therefore, in those disastrous times of weakness and persecution to talk in pompous terms of the succession of the Bishops of Rome, and make out vain catalogues of lordly prelates who sat on the throne of St. Peter, it is incontestable that, from the earliest period, the Christian converts held their meetings—by stealth indeed, and under fear of detection—and obeyed certain canons of their own constitution. These secret associations rapidly spread their ramifications into every great city of the empire. When by the friendship, or the fellowship, of the emperor, as in the case of the Arabian Philip, a pause was given to their fears and sufferings, certain buildings were set apart for their religious exercises; and we read, during this century, of basilicas, or churches, in Rome and other towns. The subtlety of the Greek intellect had already led to endless heresies and the wildest departures from the simplicity of the gospel. The Western mind was more calm, and better adapted to be the lawgiver of a new order of society composed of elements so rough and discordant as the barbarians, whose approach was now inevitably foreseen. With its well-defined hierarchy—its graduated ranks, and the fitness of the offices for the purposes of their creation; with its array of martyrs ready to suffer, and clear-headed leaders fitted to command, the Western Church could look calmly forward to the time when its organization would make it the most powerful, or perhaps the only, body in the State; and so early as the middle of this century the seeds of worldly ambition developed themselves in a schism, not on a point of doctrine, but on the possession of authority. A double nomination had made the anomalous appointment of two chief pastors at the same time. Neither would yield, and each had his supporters. All were under the ban of the civil power. They had recourse to spiritual weapons; and we read, for the first time in ecclesiastical history, of mutual excommunications. Novatian—under his breath, however, for fear of being thrown to the wild beasts for raising a disturbance—thundered his anathemas against Cornelius as an intruder, while Cornelius retorted by proclaiming Novatian an impostor, as he had not the concurrence of the people in his election. This gives us a convincing proof of the popular form of appointing bishops or presbyters in those early days, and prepares us for the energy with which the electors supported the authority of their favourite priests.

But, while this new internal element was spreading life among the decayed institutions of the empire, we have, in this century, the first appearance, in great force, of the future conquerors and renovators of the body politic from without. It is pleasant to think that the centuries cast themselves more and more loose from their connection with Rome after this date, and that the barbarians can vindicate a separate place in history for themselves. In the first century, the bad emperors broke the strength of Rome by their cruelty and extravagance. In the second century, the good emperors carried on the work of weakening the empire by the softening and enervating effects of their gentle and protective policy. The third century unites the evil qualities of the other two, for the people were equally rendered incapable of defending themselves by the unheard-of atrocities of some of the tyrants who oppressed them and the mistaken measures of the more benevolent rulers, in committing the guardianship of the citizens to the swords of a foreign soldiery, leaving them but the wretched alternative of being ravaged and massacred by an irruption of savage tribes or pillaged and insulted by those in the emperor’s pay.

The empire had long been surrounded by its foes. |A.D. 273.|It will suffice to read the long list of captives who were led in triumph behind the car of Aurelian when he returned from foreign war, to see the fearful array of harsh-sounding names which have afterwards been softened into those of great and civilized nations. It is in following the course of some of these that we shall see how the present distribution of forces in Europe took place, and escape from the polluted atmosphere of Imperial Rome. In that memorable triumph appeared Goths, Alans, Roxolans, Franks, Sarmatians, Vandals, Allemans, Arabs, Indians, Bactrians, Iberians, Saracens, Armenians, Persians, Palmyreans, Egyptians, and ten Gothic women dressed in men’s apparel and fully armed. These were, perhaps, the representatives of a large body of female warriors, and are a sign of the recent settlement of the tribe to which they belonged. They had not yet given up the habits of their march, where all were equally engaged in carrying the property and arms of the nation, and where the females encouraged the young men of the expedition by witnessing and sometimes sharing their exploits in battle.

The triumph of Probus, when only seven years had passed, presents us with a list of the same peoples, often conquered but never subdued. Their defeats, indeed, had the double effect of showing to them their own ability to recruit their forces, and of strengthening the degraded people of Rome in the belief of their invincibility. After the loss of a battle, the Gothic or Burgundian chief fell back upon the confederated tribes in his rear; a portion of his army either visited Rome in the character of captives, or enlisted in the ranks of the conquerors. In either case, the wealth of the great city and the undefended state of the empire were permanently fixed in their minds; the populace, on the other hand, had the luxury of a noble show and double rations of bread—the more ambitious of the emperors acting on the professed maxim that the citizen had no duty but to enjoy the goods provided for him by the governing power, and that if he was fed by public doles, and amused with public games, the purpose of his life was attained. The idlest man was the safest subject. A triumph was, therefore, more an instrument of degradation than an encouragement to patriotic exertion. The name of Roman citizen was now extended to all the inhabitants of the empire. The freeman of York was a Roman citizen. Had he any patriotic pride in keeping the soil of Italy undivided? The nation had become too diffuse for the exercise of this local and combining virtue. The love of country, which in the small states of Greece secured the individual’s affection to his native city, and yet was powerful enough to extend over the whole of the Hellenic territories, was lost altogether when it was required to expand itself over a region as wide as Europe. It is in this sense that empires fall to pieces by their own weight. The Roman power broke up from within. Its religion was a source of division, not of union—its mixture of nations, and tongues, and usages, lost their cohesion. And nothing was left at the end of this century to preserve it from total dissolution, but the personal qualities of some great rulers and the memory of its former fame.

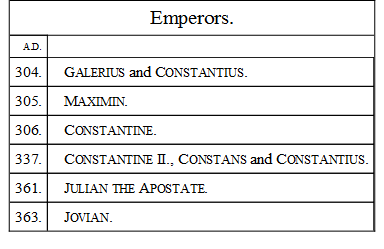

FOURTH CENTURY

Donatus, Eutropius, St. Athanasius, Ausonius, Claudian, Arnobius, (303,) Lactantius, (306,) Eusebius, (315,) Arius, (316,) Gregory Nazianzen, (320-389,) Basil the Great, Bishop Of Cesarea, (330-379,) Ambrose, (340-397,) Augustine (353-429,) Theodoret, (386-457,) Martin, Bishop of Tours.

THE FOURTH CENTURY

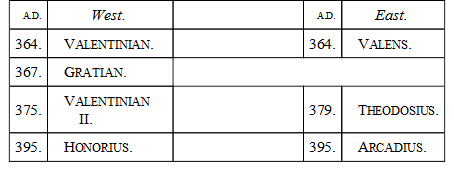

THE REMOVAL TO CONSTANTINOPLE – ESTABLISHMENT OF CHRISTIANITY – APOSTASY OF JULIAN – SETTLEMENT OF THE GOTHSAs the memory of the old liberties of Rome died out, a nearer approach was made to the ostentatious despotisms of the East. Aurelian, in 270, was the first emperor who encircled his head with a diadem; and Diocletian, in 284, formed his court on the model of the most gorgeous royalties of Asia. On admission into his presence, the Roman Senator, formerly the equal of the ruler, prostrated himself at his feet. Titles of the most unmanly adulation were lavished on the fortunate slave or herdsman who had risen to supreme power. He was clothed in robes of purple and violet, and loaded with an incalculable wealth of jewels and gold. It was from deep policy that Diocletian introduced this system. Ceremony imposes on the vulgar, and makes intimacy impossible. Etiquette is the refuge of failing power, and compensates by external show for inherent weakness, as stiffness and formality are the refuge of dulness and mediocrity in private life. There was now, therefore, seated on the throne, which was shaken by every commotion, a personage assuming more majestic rank, and affecting far loftier state and dignity, than Augustus had ventured on while the strength of the old Republic gave irresistible force to the new empire, or than the Antonines had dreamt of when the prosperity of Rome was apparently at its height. But there was still some feeling, if not of self-respect, at least of resistance to pretension, in the populace and Senators of the capital. Diocletian visited Rome but once. He was attacked in lampoons, and ridiculed in satirical songs. His colleague established his residence in the military post of Milan. We are not, therefore, to feel surprised that an Orientalized authority sought its natural seat in the land of ancient despotisms, and that many of the emperors had cast longing eyes on the beautiful towns of Asia Minor, and even on the far-off cities of Mesopotamia, as more congenial localities for their barbaric splendours. By a sort of compromise between his European origin and Asiatic tastes, the emperor Constantine, after many struggles with his competitors, having attained the sole authority, transferred the seat of empire from Rome to a city he had built on the extreme limits of Europe, and only divided from Asia by a narrow sea. All succeeding ages have agreed in extolling the situation of this city, called, after its founder, Constantinople, as the finest that could have been chosen. All ages, from the day of its erection till the hour in which we live, have agreed that it is fitted, in the hands of a great and enterprising power, to be the metropolis and arbiter of the world; and Constantinople is, therefore, condemned to the melancholy fate of being the useless and unappreciated capital of a horde of irreclaimable barbarians. To this magnificent city Constantine removed the throne in 329, and for nearly a thousand years after that, while Rome was sacked in innumerable invasions, and all the capitals of Europe were successively occupied by contending armies, Constantinople, safe in her two narrow outlets, and rich in her command of the two continents, continued unconquered, and even unassailed.

Rome was stripped, that Constantinople might be filled. All the wealth of Italy was carried across the Ægean. The Roman Senator was invited to remove with his establishment. He found, on arriving at his new home, that by a complimentary attention of the emperor, a fac-simile of his Roman palace had been prepared for him on the Propontis. The seven hills of the new capital responded to the seven hills of the old. There were villas for retirement along the smiling shores of the Dardanelles or of the Bosphorus, as fine in climate, and perhaps equal in romantic beauty, to Baiæ or Brundusium. There was a capital, as noble a piece of architecture as the one they had left, but without the sanctity of its thousand years of existence, or the glory of its unnumbered triumphs. One omission was the subject of remark and lamentation. The temples were nowhere to be seen. The images of the gods were left at Rome in the solitude of their deserted shrines, for Constantine had determined that Constantinople should, from its very foundation, be the residence of a Christian people. Churches were built, and a priesthood appointed. Yet, with the policy which characterized the Church at that time, he made as little change as possible in the external forms. There is still extant a transfer of certain properties from the old establishment to the new. There are contributions of wax for the candles, of frankincense and myrrh for the censers, and vestures for the officiating priests as before. Only the object of worship is changed, and the images of the heathen gods and heroes are replaced with statues of the apostles and martyrs.

It is difficult to gather a true idea of this first of the Christian emperors from the historians of after-times. The accounts of him by contemporary writers are equally conflicting. The favourers of the old superstition describe him as a monster of perfidy and cruelty. The Church, raised to supremacy by his favour, sees nothing in him but the greatest of men—the seer of visions, the visible favourite of the Almighty, and the predestined overthrower of the powers of evil. The easy credulity of an emancipated people believed whatever the flattery of the courtiers invented. His mother Helena made a journey to Jerusalem, and was rewarded for the pious pilgrimage by the discovery of the True Cross. Chapels and altars were raised upon all the places famous in Christian story; relics were collected from all quarters, and we are early led to fear that the simplicity of the gospel is endangered by its approach to the throne, and that Constantine’s object was rather to raise and strengthen a hierarchy of ecclesiastical supporters than to give full scope to the doctrine of truth. But not the less wonderful, not the less by the divine appointment, was this unhoped-for triumph of Christianity, that its advancement formed part of the ambitious scheme of a worldly and unprincipled conqueror. Rather it may be taken as one among the thousand proofs with which history presents us, that the greatest blessings to mankind are produced irrespective of the character or qualities of the apparent author. A warrior is raised in the desert when required to be let loose upon a worn-out society as the scourge of God; a blood-stained soldier is placed on the throne of the world when the time has come for the earthly predominance of the gospel. But neither is Attila to be blamed nor Constantine to be praised.

It was the spirit of his system of government to form every society on a strictly monarchical model. There was everywhere introduced a clearly-defined subordination of ranks and dignities. Diocletian, we saw, surrounded the throne with a state and ceremony which kept the imperial person sacred from the common gaze. Constantine perfected his work by establishing a titled nobility, who were to stand between the throne and the people, giving dignity to the one, and impressing fresh awe upon the other. In all previous ages it had been the office that gave importance to the man. To be a member of the Senate was a mark of distinction; a long descent from a great historic name was looked on with respect; and the heroic deeds of the thousand years of Roman struggle had founded an aristocracy which owed its high position either to personal actions or hereditary claims. But now that the emperors had so long concentrated in themselves all the great offices of the State—now that the bad rulers of the first century had degraded the Senate by filling it with their creatures, the good rulers of the second century had made it merely the recorder of their decrees, and the anarchy of the third century had changed or obliterated its functions altogether—there was no way left to the ambitious Roman to distinguish himself except by the favour of the emperor. The throne became, as it has since continued in all strictly monarchical countries, the fountain of honour. It was not the people who could name a man to the consulship or appoint him to the command of an army. It was not even in the power of the emperor to find offices of dignity for all whom he wished to advance. So a method was discovered by which vanity or friendship could be gratified, and employment be reserved for the deserving at the same time. Instead of endangering an expedition against the Parthians by intrusting it to a rich and powerful courtier who desired to have the rank of general, the emperor simply named him Nobilissimus, or Patricius, or Illustris, and the gratified favourite, the “most noble,” the “patrician,” or the “illustrious,” took place with the highest officers of the State. A certain title gave him equal rank with the Senator, the judge, or the consul. The diversity of these honorary distinctions became very great. There were the clarissimi—the perfectissimi—and the egregii—bearing the same relative dignity in the court-guide of the fourth century, as the dukes, marquises, earls, and viscounts of the peerage-books of the present day. But so much did all distinction flow from proximity to the throne, that all these high-sounding names owed their value to the fact of their being bestowed on the associates of the sovereign. The word Count, which is still the title borne by foreign nobles, comes from the Latin word which means “companion.” There was a Comes, or Companion, of the Sacred Couch, or lord chamberlain—the Companion of the Imperial Service, or lord high steward—a Companion of the Imperial Stables, or lord high constable; through all these dignitaries, step above step, the glorious ascent extended, till it ended in the Companion of Private Affairs, or confidential secretary. At the head of all, sacred and unapproachable, stood the embodied Power of the Roman world, who, as he had given titles to all the magnates of his court, heaped also a great many on himself. His principal appellation, however, was not as in our degenerate days “Majesty,” whether “Most Catholic,” “Most Christian,” or “Most Orthodox,” but consisted in the rather ambitious attribute—eternity. “Your Eternity” was the phrase addressed to some miserable individual whose reign was ended in a month. It was proposed by this division of the Roman aristocracy to furnish the empire with a body for show and a body for use; the latter consisting of the real generals of the armies and administrators of the provinces. And with this view the two were kept distinct; but military discipline suffered by this partition. The generals became discontented when they saw wealth and dignities heaped upon the titular nobles of the court; and to prevent the danger arising from ill will among the legions on the frontier, the emperor withdrew the best of his soldiers from the posts where they kept the barbarians in check, and entirely destroyed their military spirit by separating them into small bodies and stationing them in towns. This exposed the empire to the foreign foes who still menaced it from the other side of the boundary, and gave fresh settlements in the heart of the country to the thousands of barbarian youth who had taken service with the eagles. In every legion there was a considerable proportion of this foreign element: in every district of the empire, therefore, there were now settled the advanced guards of the unavoidable invasion. Men with barbaric names, which the Romans could not pronounce, walked about Roman towns dressed in Roman uniforms and clothed with Roman titles. There were consulars and patricians in Ravenna and Naples, whose fathers had danced the war-dance of defiance when beginning their march from the Vistula and the Carpathian range.

All these troops must be supported—all these dignitaries maintained in luxury. How was this done? The ordinary revenue of the empire in the time of Constantine has been computed at forty millions of our money a year. Not a very large amount when you consider the number of the population; but this is the sum which reached the treasury. The gross amount must have been far larger, and an ingenious machinery was invented by which the tax was rigorously collected; and this machinery, by a ludicrous perversion of terms, was made to include one of the most numerous classes of the artificial nobility created by the imperial will. In all the towns of the empire some little remains were still to be found of the ancient municipal government, of which practically they had long been deprived. There were nominal magistrates still; and among these the Curials held a distinguished rank. They were the men who, in the days of freedom, had filled the civic dignities of their native city—the aldermen, we should perhaps call them, or, more nearly, the justices of the peace. They were now ranked with the peerage, but with certain duties attached to their elevation which few can have regarded in the light of privilege or favour. To qualify them for rank, they were bound to be in possession of a certain amount of land. They were, therefore, a territorial aristocracy, and never was any territorial aristocracy more constantly under the consideration of the government. It was the duty of the curials to distribute the tax-papers in their district; but, in addition to this, it was unfortunately their duty to see that the sum assessed on the town and neighbourhood was paid up to the last penny. When there was any deficiency, was the emperor to suffer? Were the nobilissimi, the patricii, the egregii, to lose their salaries? Oh, no! As long as the now ennobled curial retained an acre of his estate, or could raise a mortgage on his house, the full amount was extracted. The tax went up to Rome, and the curial, if there had been a poor’s house in those days, would have gone into it—for he was stripped of all. His farm was seized, his cattle were escheated; and when the defalcation was very great, himself, his wife and children were led into the market and sold as slaves. Nothing so rapidly destroyed what might have been the germ of a middle class as this legalized spoliation of the smaller landholders. Below this rank there was absolutely nothing left of the citizenship of ancient times. Artificers and workmen formed themselves into companies; but the trades were exercised principally by slaves for the benefit of their owners. These slaves formed now by far the greatest part of the Roman population, and though their lot had gradually become softened as their numbers increased, and the domestic bondsman had little to complain of except the greatest of all sorrows, the loss of freedom, the position of the rural labourers was still very bad. There were some of them slaves in every sense of the word—mere chattels, which were not so valuable as horse or dog. But the fate of others was so far mitigated that they could not be sold separate from their family—that they could not be sold except along with the land; and at last glimpses appear of a sort of rent paid for certain portions of the lord’s estate in full of all other requirements. But this process had again to be gone through when many centuries had elapsed, and a new state of society had been fully established, and it will be sufficient to remind you that in the fourth century, to which we are now come, the Roman world consisted of a monarchy where all the greatness and magnificence of the empire were concentrated on the emperor and his court; that the monarchical system was rapidly pervading the Church; and that below these two distinct but connected powers there was no people, properly so called—the country was oppressed and ruined, and the ancient dignity of Rome transplanted to new and foreign quarters, at the sacrifice of all its oldest and most elevating associations. The half-depopulated city of Romulus and the Kings—of the Consuls and Augustus, looked with ill-disguised hatred and contempt on the modern rival which denied her the name of Capital, and while fresh from the builder’s hand, robbed her of the name of the Eternal City. We shall see great events spring from this jealousy of the two towns. In the mean time, we shall finish our view of Constantine by recording the greatness of his military skill, and merely protest against the enrolment in the list of saints of a man who filled his family circle with blood—who murdered his wife, his son, and his nephew, encouraged the contending factions of the now disputatious Church—gave a fallacious support to the orthodox Athanasius, and died after a superstitious baptism at the hands of the heretical Arius. |A.D. 337.|An unbiassed judgment must pronounce him a great politician, who played with both parties as his tools, a Christian from expediency and not from conviction. It is a pity that the subserviency of the Greek communion has placed him in the number of its holy witnesses, for we are told by a historian that when the emperor, after the dreadful crimes he had perpetrated, applied at the heathen shrines for expiatory rites, the priests of the false gods had truly answered, “there are no purifications for such deeds as these.” But nothing could be refused to the benefactor of the Church. The great ecclesiastical council of this age, (325), consisting of three hundred and eighteen bishops, and presided over by Constantine in person, gave the Nicene Creed as the result of their labours—a creed which is still the symbol of Christendom, but which consists more of a condemnation of the heresies which were then in the ascendant, than in the plain enunciation of the Christian faith. A layman, we are told, an auditor of the learned debates in this great assembly, a man of clear and simple common sense, met some of the disputants, and addressed them in these words:—“Arguers! Christ and his apostles delivered to us, not the art of disputation, nor empty eloquence, but a plain and simple rule which is maintained by faith and good works.” The disputants, we are further told, were so struck with this undeniable truth that they acknowledged their error at once.