полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

|A.D. 181.|

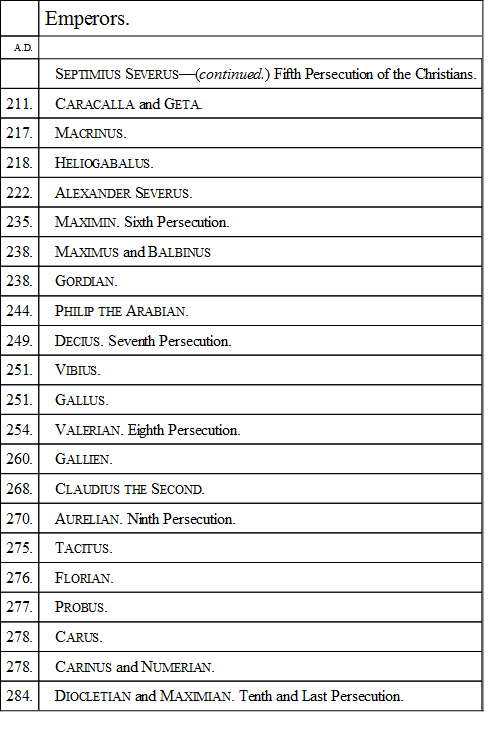

With the death of the excellent Marcus Aurelius the golden age came to a close. Commodus sat on the throne, and renewed the wildest atrocities of the previous century. Nero was not more cruel—Domitian was not so reckless of human life. He fought in the arena against weakly-armed adversaries, and slew them without remorse. He polluted the whole city with blood, and made money by selling permissions to murder. Thirteen years exhausted the patience of the world, and a justifiable assassination put an end to his life. There was an old man of the name of Pertinax, originally a nickname derived from his obstinate or pertinacious disposition, who now made his appearance on the throne and perished in three months. It chanced that a certain rich man of the name of Didius was giving a supper the night of the murder to some friends. The dishes were rich, and the wine delicious. Inspired by the good cheer, the guests said, “Why don’t you buy the empire? The soldiers have proclaimed that they will give it to the highest bidder.” Didius knew the amount of his treasure, and was ambitious: he got up from table and hurried to the Prætorian camp. On the way he met the mutilated body of the murdered Pertinax, dragged through the streets with savage exultation. Nothing daunted, he arrived at the soldiers’ tents. Another had been before him—Sulpician, the father-in-law and friend of the late emperor. A bribe had been offered to each soldier, so large that they were about to conclude the bargain; but Didius bade many sesterces more. The greedy soldiery looked from one to the other, and shouted with delight, as each new advance was made. |A.D. 193.|At last Sulpician was silent, and Didius had purchased the Roman world at the price of upwards of £200 to each soldier of the Prætorian guard. He entered the palace in state, and concluded the supper, which had been interrupted at his own house, on the viands prepared for Pertinax. But the excitement of the auction-room was too pleasant to be left to the troops in Rome. Offers were made to the legions in all the provinces, and Didius was threatened on every side. Even the distant garrisons of Britain named a candidate for the throne; and Claudius Albinus assumed the imperial purple, and crossed over into Gaul. More irritated still, the army in Syria elected its general, Pescennius Niger, emperor, and he prepared to dispute the prize; but quietly, steadily, with stern face and unrelenting heart, advancing from province to province, keeping his forces in strict subjection, and laying claim to supreme authority by the mere strength of his indomitable will, came forward Septimius Severus, and both the pretenders saw that their fate was sealed. Illyria and Gaul recognised his title at once. Albinus was happy to accept from him the subordinate title of Cæsar, and to rule as his lieutenant. Didius, whose bargain turned out rather ill, besought him to be content with half the empire. Severus slew the messengers who brought this proposition, and advanced in grim silence. The Senate assembled, and, by way of a pleasant reception for the Illyrian chief, requested Didius to prepare for death. The executioners found him clinging to life with unmanly tenacity, and killed him when he had reigned but seventy days. One other competitor remained, the general of the Syrian army—the closest friend of Severus, but now separated from him by the great temptation of an empire in dispute. This was Niger, from whom an obstinate resistance was expected, as he was equally famous for his courage and his skill. But fortune was on the side of Severus. Niger was conquered after a short struggle, and his head presented to the victor. Was Albinus still to live, and approach so near the throne as to have the rank of Cæsar? Assassins were employed to murder him, but he escaped their assault. The treachery of Severus brought many supporters to his rival. The Roman armies were ranged in hostile camps. Severus again was fortunate, and Albinus, dashing towards him to engage in combat, was slain before his eyes. He watched his dying agonies for some time, and then forced his horse to trample on the corpse. A man of harsh, implacable nature—not so much cruel as impenetrable to human feelings, and perhaps forming a just estimate of the favourable effect upon his fortunes of a disposition so calm, and yet so relentless. The Prætorians found they had appointed their master, and put the sword into his hand. He used it without remorse. He terrified the boldest with his imperturbable stillness; he summoned the seditious soldiery to wait on him at his camp. They were to come without arms, without their military dress, almost like suppliants, certainly not like the ferocious libertines they had been when they had sold the empire at the highest price. “Whoever of you wishes to live,” said Severus, frowning coldly, “will depart from this, and never come within thirty leagues of Rome. Take their horses,” he added to the other troops who had surrounded the Prætorians, “take their accoutrements, and chase them out of my sight.” Did the Senate receive a milder treatment? On sending them the head of Albinus, he had written to the Conscript Fathers alarming them with the most dreadful threats. And now the time of execution had come. He made them an oration in praise of the proscriptions of Marius and Sylla, and forced them to deify the tyrant Commodus, who had hated them all his life. He then gave a signal to his train, and the streets ran with blood. All who had borne high office, all who were of distinguished birth, all who were famous for their wealth or popular with the citizens, were put to death. He crossed over to England and repressed a sedition there. His son Caracalla accompanied him, and commenced his career of warlike ardour and frightful ferocity, which can only be explained on the ground of his being mad. He tried even to murder his father, in open day, in the sight of the soldiers. He was stealing upon the old man, when a cry from the legion made him turn round. His inflexible eye fell upon Caracalla—the sword dropped from his unfilial hand—and dreadful anticipations of vengeance filled the assembly. The son was pardoned, but his accomplices, whether truly or falsely accused, perished by cruel deaths. At last the emperor felt his end approach. He summoned his sons Caracalla and Geta into his presence, recommended them to live in unity, and ended by the advice which has become the standing maxim of military despots, “Be generous to the soldiers, and trample on all beside.”

With this hideous incarnation of unpitying firmness on the throne—hopeless of the future, and with dangers accumulating on every side, the Second Century came to an end, leaving the amazing contrast between its miserable close and the long period of its prosperity by which it will be remembered in all succeeding time.

THIRD CENTURY

Clement of Alexandria, Dion Cassius, Origen, Cyprian, Plotinus, Longinus, Hippolitus Portuensis, Julius Africanus Celsus, Origen.

THE THIRD CENTURY

ANARCHY AND CONFUSION – GROWTH OF THE CHRISTIAN CHURCHWe are now in the twelfth year of the Third Century. Septimius Severus has died at York, and Caracalla is let loose like a famished tiger upon Rome. He invites his brother Geta to meet him to settle some family feud in the apartment of their mother, and stabs him in her arms. The rest of his reign is worthy of this beginning, and it would be fatiguing and perplexing to the memory to record his other acts. Fortunately it is not required; nor is it necessary to follow minutely the course of his successors. What we require is only a general view of the proceedings of this century, and that can be gained without wading through all the blood and horrors with which the throne of the world is surrounded. Conclusive evidence was obtained in this century that the organization of Roman government was defective in securing the first necessities of civilized life. When we talk of civilization, we are too apt to limit the meaning of the word to its mere embellishments, such as arts and sciences; but the true distinction between it and barbarism is, that the one presents a state of society under the protection of just and well-administered law, and the other is left to the chance government of brute force. There was now great wealth in Rome—great luxury—a high admiration of painting, poetry, and sculpture—much learning, and probably infinite refinement of manners and address. But it was not a civilized state. Life was of no value—property was not secure. A series of madmen seized supreme authority, and overthrew all the distinctions between right and wrong. Murder was legalized, and rapine openly encouraged. It is a sort of satisfaction to perceive that few of those atrocious malefactors escaped altogether the punishment of their crimes. If Caracalla slays his brother and orders a peaceable province to be destroyed, there is a Macrinus at hand to put the monster to death. |A.D. 218.|But Macrinus, relying on the goodness of his intentions, neglects the soldiery, and is supplanted by a boy of seventeen—so handsome that he won the admiration of the rudest of the legionaries, and so gentle and captivating in his manners that he strengthened the effect his beauty had produced. He was priest of the Temple of the Sun at Emesa in Phœnicia; and by the arts of his grandmother, who was sister to one of the former empresses, and the report that she cunningly spread abroad that he was the son of their favourite Caracalla, the affection of the dissolute soldiery knew no bounds. Macrinus was soon slaughtered, and the long-haired priest of Baal seated on the throne of the Cæsars, under the name of Heliogabalus. As might be expected, the sudden alteration in his fortunes was fatal to his character. All the excesses of his predecessors were surpassed. His extravagance rapidly exhausted the resources of the empire. His floors were spread with gold-dust. His dresses, jewels, and golden ornaments were never worn twice, but went to his slaves and parasites. He created his grandmother a member of the Senate, with rank next after the consuls; and established a rival Senate, composed of ladies, presided over by his mother. Their jurisdiction was not very hurtful to the State, for it only extended to dresses and precedence of ranks, and the etiquette to be observed in visiting each other. But the evil dispositions of the emperor were shown in other ways. He had a cousin of the name of Alexander, and entertained an unbounded jealousy of his popularity with the soldiers. Attempts at poison and direct assassination were resorted to in vain. The public sympathy began to rise in his favour. The Prætorians formally took him under their protection; and when Heliogabalus, reckless of their menaces, again attempted the life of Alexander, the troops revolted, proclaimed death to the infatuated emperor, and slew him and his mother at the same time.

A.D. 222Alexander was now enthroned—a youth of sixteen; gifted with higher qualities than the debased century in which he lived could altogether appreciate. But the origin of his noblest sentiments is traced to the teaching he had received from his mother, in which the precepts of Christianity were not omitted. When he appointed the governor of a province, he published his name some time before, and requested if any one knew of a disqualification, to have it sent in for his consideration. “It is thus the Christians appoint their pastors,” he said, “and I will do the same with my representatives.” When his justice, moderation, and equity were fully recognised, the beauty of the quotation, which was continually in his mouth, was admired by all, even though they were ignorant of the book it came from: “Do unto others as you would that they should do unto you.” He trusted the wisest of his counsellors, the great legalists of the empire, with the introduction of new laws to curb the wickedness of the time. But the multiplicity of laws proves the decline of states. In the ancient Rome of the kings and earlier consuls, the statutes were contained in forty decisions, which were afterwards enlarged into the laws of the Twelve Tables, consisting of one hundred and fifty texts. The profligacy of some emperors, the vanity of others, had loaded the statute-book with an innumerable mass of edicts, senatus-consultums, prætorial rescripts, and customary laws. It was impossible to extract order or regularity from such a chaos of conflicting rules. The great work was left for a later prince; at present we can only praise the goodness of the emperor’s intention. But Alexander, justly called Severus, from the simplicity of his life and manners, has held the throne too long. The Prætorians have been thirteen years without the donation consequent on a new accession.

Among the favourite leaders selected by Alexander for their military qualifications was one Maximin, a Thracian peasant, of whose strength and stature incredible things are told. He was upwards of eight feet high, could tire down a horse at the gallop on foot, could break its leg by a blow of his hand, could overthrow thirty wrestlers without drawing breath, and maintained this prodigious force by eating forty pounds of meat, and drinking an amphora and a half, or twelve quarts, of wine. This giant had the bravery for which his countrymen the Goths have always been celebrated. He rose to high rank in the Roman service; and when at last nothing seemed to stand between him and the throne but his patron and benefactor, ambition blinded him to every thing but his own advancement. He murdered the wise and generous Alexander, and presented for the first time in history the spectacle of a barbarian master of the Roman world. Other emperors had been born in distant portions of the empire; an African had trampled on Roman greatness in the person of Septimius Severus; a Phœnician priest had disgraced the purple in the person of Heliogabalus; Africa, however, was a Roman province, and Emesa a Roman town. But here sat the colossal representative of the terrible Goths of Thrace, speaking a language half Getic, half Latin, which no one could easily understand; fierce, haughty, and revengeful, and cherishing a ferocious hatred of the subjects who trembled before him—a hatred probably implanted in him in his childhood by the patriotic songs with which the warriors of his tribe kept alive their enmity and contempt for the Roman name. The Roman name had indeed by this time lost all its authority. The army, recruited from all parts of the empire, and including a great number of barbarians in its ranks, was no longer a bulwark against foreign invasion. Maximin, bestowing the chief commands on Pannonians and other mercenaries, treated the empire as a conquered country. He seized on all the wealth he could discover—melted all the golden statues, as valuable from their artistic beauty as for the metal of which they were composed—and was threatening an approach to Rome to exterminate the Senate and sack the devoted town. In this extremity the Senate resumed its long-forgotten power, and named as emperors two men of the name of Gordian—father and son—with instructions “to resist the enemy.” But father and son perished in a few weeks, and still the terrible Goth came on. His son, a giant like himself, but beautiful as the colossal statue of a young Apollo, shared in all the feelings of his father. Terrified at its approaching doom, the Senate once more nominated two men to the purple, Maximus and Balbinus: Balbinus, the favourite, perhaps, of the aristocracy, by the descent he claimed from an illustrious ancestry; while Maximus recommended himself to the now perverted taste of the commonalty by having been a carter. Neither was popular with the army; and, to please the soldiers, a son or nephew of the younger Gordian was associated with them on the throne. But nothing could have resisted the infuriated legions of the gigantic Maximin; they were marching with wonderful expedition towards their revenge. At Aquileia they met an opposition; the town shut its gates and manned its walls, for it knew what would be the fate of a city given up to the tender mercies of the Goths. Meanwhile the approach of the destroyer produced great agitation in Rome. The people rose upon the Prætorians, and enlisted the gladiators on their side. Many thousands were slain, and at last a peace was made by the intercession of the youthful Gordian. Glad of the cessation of this civic tumult, the population of Rome betook itself to the theatres and shows. Suddenly, while the games were going on, it was announced that the army before Aquileia had mutinied and that both the Maximins were slain. |A.D. 235.|All at once the amphitheatre was emptied; by an impulse of grateful piety, the emperors and people hurried into the temples of the gods, and offered up thanks for their deliverance. The wretched people were premature in their rejoicing. In less than three months the spoiled Prætorians were offended with the precaution taken by the emperors in surrounding themselves with German guards. They assaulted the palace, and put Maximus and Balbinus to death. Gordian the Third was now sole emperor, and the final struggle with the barbarians drew nearer and nearer.

Constantly crossing the frontiers, and willingly received in the Roman ranks, the communities who had been long settled on the Roman confines were not the utterly uncultivated tribes which their name would seem to denote. There was a conterminous civilization which made the two peoples scarcely distinguishable at their point of contact, but which died off as the distance from the Roman line increased. Thus, an original settler on the eastern bank of the Rhine was probably as cultivated and intelligent as a Roman colonist on the other side; but farther up, at the Weser and the Elbe, the old ferocity and roughness remained. Fresh importations from the unknown East were continually taking place; the dwellers in the plains of Pannonia, now habituated to pasturage and trade, found safety from the hordes which pressed upon them from their own original settlements beyond the Caucasus, by crossing the boundary river; and by this means the banks were held by cognate but hostile peoples, who could, however, easily be reconciled by a joint expedition against Rome. New combinations had taken place in the interior of the great expanses not included in the Roman limits. The Germans were no longer the natural enemies of the empire. They furnished many soldiers for its defence, and several chiefs to command its forces. But all round the external circuit of those half-conciliated tribes rose up vast confederacies of warlike nations. There were Cheruski, and Sicambri, and Attuarians, and Bruttuarians, and Catti, all regularly enrolled under the name of “Franks,” or the brave. The Sarmatians or Sclaves performed the same part on the northeastern frontier; and we have already seen that the irresistible Goths had found their way, one by one, across the boundary, and cleared the path for their successors. The old enemies of Rome on the extreme east, the Parthians, had fallen under the power of a renovated mountain-race, and of a king, who founded the great dynasty of the Sassanides, and claimed the restoration of Egypt and Armenia as ancient dependencies of the Persian crown. To resist all these, there was, in the year 241, only a gentle-tempered youth, dressed in the purple which had so lost its original grandeur, and relying for his guidance on the wisdom of his tutors, and for his life on the forbearance of the Prætorians. The tutors were wise and just, and victory at first gave some sort of dignity to the reign of Gordian. |A.D. 244.|The Franks were conquered at Mayence; but Gordian, three years after, was murdered in the East; and Philip, an Arabian, whose father had been a robber of the desert, was acknowledged emperor by senate and army. Treachery, ambition, and murder pursued their course. There was no succession to the throne. Sometimes one general, luckier or wiser than the rest, appeared the sole governor of the State. At other times there were numberless rivals all claiming the empire and threatening vengeance on their opponents. Yet amidst this tumult of undistinguishable pretenders, fortune placed at the head of affairs some of the best and greatest men whom the Roman world ever produced. There was Valerian, whom all parties agreed in considering the most virtuous and enlightened man of his time. |A.D. 253.|Scarcely any opposition was made to his promotion; and yet, with all his good qualities, he was the man to whom Rome owed the greatest degradation it had yet sustained. He was taken prisoner by Sapor, the Persian king, and condemned, with other captive monarchs, to draw the car of his conqueror. No offers of ransom could deliver the brave and unfortunate prince. He died amid his deriding enemies, who hung up his skin as an offering to their gods. Then, after some years, in which there were twenty emperors at one time, with army drawn up against army, and cities delivered to massacre and rapine by all parties in turn, there arose one of the strong minds which make themselves felt throughout a whole period, and arrest for a while the downward course of states. |A.D. 276.|The emperor Probus, son of a man who had originally been a gardener, had distinguished himself under Aurelian, the conqueror of Palmyra, and, having survived all his competitors, had time to devote himself to the restoration of discipline and the introduction of purer laws. His victories over the encroaching barbarians were decided, but ineffectual. New myriads still pressed forward to take the place of the slain. On one occasion he crossed the Rhine in pursuit of the revolted Germans, overtook them at the Necker, and killed in battle four hundred thousand men. Nine kings threw themselves at the emperor’s feet. Many thousand barbarians enlisted in the Roman army. Sixty great cities were taken, and made offerings of golden crowns. The whole country was laid waste. “There was nothing left,” he boasted to the Senate, “but bare fields, as if they had never been cultivated.” So much the worse for the Romans. The barbarians looked with keener eyes across the river at the rich lands which had never been ravaged, and sent messages to all the tribes in the distant forests, that, having no occasion for pruning-hooks, they had turned them into swords. But Probus showed a still more doubtful policy in other quarters. When he conquered the Vandals and Burgundians, he sent their warriors to keep the Caledonians in subjection on the Tyne. The Britons he transported to Mœsia or Greece. What intermixtures of race may have arisen from these transplantations it is impossible to say; but the one feeling was common to all the barbarians, that Rome was weak and they were strong. He settled a large detachment of Franks on the shores of the Black Sea; and of these an almost incredible but well-authenticated story is told. They seized or built themselves boats. They swept through the Dardanelles, and ravaged the isles of Greece. They pursued their piratical career down the Mediterranean, passed the pillars of Hercules into the Great Sea, and, rounding Spain and France, rowed up the Elbe into the midst of their astonished countrymen, who had long given them up for dead. A fatal adventure this for the safety of the Roman shores; for there were the wild fishermen of Friesland, and the audacious Angles of Schleswig and Holstein, who heard of this strange exploit, and saw that no coast was too distant to be reached by their oar and sail. But if these forced settlements of barbarians on Roman soil were impolitic, the generous Probus did not feel their bad effect. His warlike qualities awed his foes, and his inflexible justice was appreciated by the hardy warriors of the North, who had not yet sunk under the debasing civilization of Rome. In Asia his arms were attended with equal success. He subdued the Persians, and extended his conquests into Ethiopia and the farthest regions of the East, bringing back some of its conquered natives to swell the triumph at Rome and terrify the citizens with their strange and hideous appearance. But Probus himself must yield to the law which regulated the fate of Roman emperors. He died by treachery and the sword. All that the empire could do was to join in the epitaph pronounced over him by the barbarians, “Here lies the emperor Probus, whose life and actions corresponded to his name.”