полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

Somewhere up between the Aller and the Oder there had been settled, from some unknown period, a people of wild and uncultivated habits, who had occasionally appeared in small detachments in the various gatherings of barbarians who had forced their way into the South. Following the irresistible impulse which seems to impel all the settlers in the North, they traversed the regions already occupied by the Heruleans and the Gepides, and paused, as all previous invasions had done, on the outer boundary of the Danube. These were the Longobards or Lombards, so called from the spears, bardi, with which they were armed; and not long they required to wait till a favourable opportunity occurred for them to cross the stream. In the hurried levies of Narses some of them had offered their services, and had been present at the victory over Totila the Goth. They returned, in all probability, to their companions, and soon the hearts of the whole tribe were set upon the conquest of the beautiful region their countrymen had seen. If they hesitated to undertake so long an expedition, two incidents occurred which made it indispensable. Flying in wild fury and dismay from the face of a pursuing enemy, the Avars, themselves a ferocious Asiatic horde which had terrified the Eastern Empire, came and joined themselves to the Lombards. With united forces, all their tents, and wives and children, their horses and cattle, this dreadful alliance began their progress to Italy. The other incident was, that in revenge for the injustice of his master, and dreading his further malice, Narses himself invited their assistance. Alboin, the Lombard king, was chief of the expedition. He had been refused the hand of Rosamund, the daughter of Cunimond, chief of the Gepides. He poured the combined armies of Lombards and Avars upon the unfortunate tribe, slew the king with his own hand, and, according to the inhuman fashion of his race, formed his drinking-cup of his enemy’s skull. He married Rosamund, and pursued his victorious career. He crossed the Julian Alps, made himself master of Milan and the dependent territories, and was lifted on the shield as King of Italy. At a festival in honour of his successes, he forced his favourite wine-goblet into the hands of his wife. She recognised the fearful vessel, and shuddered while she put her lips to the brim. But hatred took possession of her heart. She promised her hand and throne to Kilmich, one of her attendants, if he would take vengeance on the tyrant who had offered her so intolerable a wrong. The attendant was won by the bride, and slew Alboin. But justice pursued the murderers. They were discovered, and fled to Ravenna, where the Exarch held his court. Saved thus from human retribution, Rosamund brought her fate upon herself. Captivated with the prospect of marrying the Exarch, she presented a poisoned cup to Kilmich, now become her husband, as he came from the bath. The effect was immediate, and the agonies he felt told him too surely the author of his death. |A.D. 575.|He just lived long enough to stab the wretched woman with his dagger, and this frightful domestic tragedy was brought to a close.

Alboin had divided his dominion into many little states and dukedoms. A kind of anarchy succeeded the strong government of the remorseless and clear-sighted king, and enemies began to arise in different directions. The Franks from the south of France began to cross the Alps. The Greek settlements began to menace the Lombards from the South. Internal disunion was quelled by the public danger, and Antharis, the son of Cleph, was nominated king. To strengthen himself against the orthodox Franks, he professed himself a Christian and joined the Arian communion. With the aid of his co-religionists he repelled the invaders, and had time, in the intervals of their assaults, to extend his conquests to the south of the peninsula. There he overthrew the settlements which owned the Empire of the East; and coming to the extreme end of Italy, the savage ruler pushed his war-horse into the water as deep as it would go, and, standing up in his stirrups, threw forward his javelin with all his strength, saying, “That is the boundary of the Lombard power.” Unhappily for the unity of that distracted land, the warrior’s boast was unfounded, and it has continued ever since a prey to discord and division. |A.D. 591.|Another kingdom, however, was added to the roll of European states; and this was the last settlement permanently made on the old Roman territory.

The Lombards were a less civilized horde than any of their predecessors. The Ostrogoths had rapidly assimilated themselves to the people who surrounded them, but the Lombards looked with haughty disdain on the population they had subdued. By portioning the country among the chiefs of the expedition, they commenced the first experiment on a great scale of what afterwards expanded into the feudal system. There were among them, as among the other northern settlers, an elective king and an hereditary nobility, owing suit and service to their chief, and exacting the same from their dependants; and already we see the working of this similarity of constitution in the diffusion throughout the whole of Europe of the monarchical and aristocratic principle, which is still the characteristic of most of our modern states. From this century some authors date the origin of what are called the “Middle Ages,” forming the great and obscure gulf between ancient and modern times. Others, indeed, wish to fix the commencement of the Middle Ages at a much earlier date—even so far back as the reign of Constantine. They found this inclination on the fact that to him we are indebted for the settlement of barbarians within the empire, and the institution of a titled nobility dependent on the crown. But many things were needed besides these to constitute the state of manners and polity which we recognise as those of the Middle Ages, and above them all the establishment of the monarchical principle in ecclesiastical government, and the recognition of a sovereign priest. This was now close at hand, and its approach was heralded by many appearances.

How, indeed, could the Church deprive itself of the organization which it saw so powerful and so successful in civil affairs? A machinery was all ready to produce an exact copy of the forms of temporal administration. There were bishops to be analogous to the great feudataries of the crown; priests and rectors to represent the smaller freeholders dependent on the greater barons; but where was the monarch by whom the whole system was to be combined and all the links of the great chain held together by a point of central union? The want of this had been so felt, that we might naturally have expected a claim to universal superiority to have long ere this been made by a Pope of Rome, the ancient seat of the temporal power. But with his residence perpetually a prey to fresh inroads, a heretical king merely granting him toleration and protection, the pretension would have been too absurd during the troubles of Italy, and it was not advanced for several years. The necessity of the case, however, was such, that a voice was heard from another quarter calling for universal obedience, and this was uttered by the Patriarch of Constantinople. Rome, we must remember, had by this time lost a great portion of her ancient fame. It was reserved for this wonderful city to rise again into all her former grandeur, by the restoration of learning and the knowledge of what she had been. At this period all that was known of her by the ignorant barbarians was, that she was a fresh-repaired and half-peopled town, which had been sacked and ruined five times within a century, that her inhabitants were collected from all parts of the world, and that she was liable to a repetition of her former misfortunes. They knew nothing of the great men who had raised her to such pre-eminence. She had sunk even from being the capital of Italy, and could therefore make no intelligible claim to be considered the capital of the world. Constantinople, on the other hand, which, by our system of education, we are taught to look upon as a very modern creation compared with the Rome of the old heroic ages of the kings and consuls, was at that period a magnificent metropolis, which had been the seat of government for three hundred years. The majesty of the Roman name had transferred itself to that new locality, and nothing was more natural than that the Patriarch of the city of Constantine, which had been imperial from its origin, and had never been defiled by the presence of a Pagan temple, should claim for himself and his see a pre-eminence both in power and holiness. Accordingly, a demand was made in 588 for the recognition throughout the Christian world of the universal headship of the bishopric of Constantinople. But at that time there was a bishop of Rome, whom his successors have gratefully dignified with the epithet of Great, who stood up in defence, not of his own see only, but of all the bishoprics in Europe. Gregory published, in answer to the audacious claim of the Eastern patriarch, a vigorous protest, in which these remarkable words occur:—“This I declare with confidence, that whoso designates himself Universal Priest, or, in the pride of his heart, consents to be so named—he is the forerunner of Antichrist.” It was therefore to Rome, on the broad ground of the Christian equality of all the chief pastors of the Church, that we owe this solemn declaration against the pretensions of the ambitious John of Constantinople.

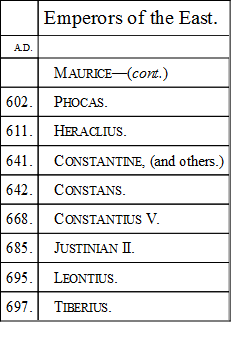

But Constantinople itself was about to fade from the minds of men. Dissatisfied with the opposition to its supremacy, the Eastern Church became separated in interest and discipline and doctrine from its Western branch. The intercourse between the two was hostile, and in a short time nearly ceased. The empire also was so deeply engaged in defending its boundaries against the Persians and other enemies in Asia, that it took small heed of the proceedings of its late dependencies, the newly-founded kingdoms in Europe. It is probable that the refined and ostentatious court of Justinian, divided as it was into fanatical parties about some of the deepest and some of the most unimportant mysteries of the faith, and contending with equal bitterness about the charioteers of the amphitheatre according as their colours were green or blue, looked with profound contempt on the struggles after better government and greater enlightenment of the rabble of Franks, and Lombards, and Burgundians, who had settled themselves in the distant lands of the West. The interior regulations of Justinian formed a strange contrast with the grandeur and success of his foreign policy. By his lieutenants Belisarius and Narses, he had reconquered the lost inheritance of his predecessors, and held in full sovereignty for a while the fertile shores of Africa, rescued from the debasing hold of the Vandals; he had cleared Italy of Ostrogoths, Spain even had yielded an unwilling obedience, and his name was reverenced in the great confederacy of the Germanic peoples who held the lands from the Atlantic eastward to Hungary, and from Marseilles to the mouth of the Elbe. But his home was the scene of every weakness and wickedness that can disgrace the name of man. Kept in slavish submission to his wife, he did not see, what all the rest of the world saw, that she was the basest of her sex, and a disgrace to the place he gave her. Beginning as a dancer at the theatre, she passed through every grade of infamy and vice, till the name of Theodora became a synonym for every thing vile and shameless. Yet this man, successful in war and politic in action, though contemptible in private life, had the genius of a legislator, and left a memorial of his abilities which extended its influence through all the nations which succeeded to any portion of the Roman dominion, and has shaped and modified the jurisprudence of all succeeding times. He was not so much a maker of new laws, as a restorer and simplifier of the old; and as the efforts of Justinian in this direction were one of the great features by which the sixth century is distinguished, it will be useful to devote a page or two to explain in what his work consisted.

The Roman laws had become so numerous and so contradictory that the administration of justice was impossible, even where the judges were upright and intelligent. The mere word of an emperor had been considered a decree, and legally binding for all future time. No lapse of years seems to have brought a law once promulgated into desuetude. The people, therefore, groaned under the uncertainty of the statutes, which was further increased by the innumerable glosses or interpretations put upon them by the lawyers. All the decisions which had ever been given by the fifty-four emperors, from Adrian to Justinian, were in full force. All the commentaries made upon them by advocates and judges, and all the sentences delivered in accordance with them, were contained in thousands of volumes; and the result was, when Justinian came to the throne in 526, that there was no point of law on which any man could be sure. He employed the greatest jurisconsults of that time, Trebonian and others, to bring some order into the chaos; and such was the diligence of the commissioners, that in fourteen months they produced the Justinian Code in twelve books, containing a condensation of all previous constitutions. A.D. 527.In the course of seven years, two hundred laws and fifty judgments were added by the emperor himself, and a new edition of the Code was published in 534. |A.D. 533.|Under the name of Institutes appeared a new manual for the legal students in the great schools of Constantinople, Berytus, and Rome, where the principles of Roman law are succinctly laid down. The third of his great works was one for the completion of which he gave Trebonian and his assessors ten years. It is called the Digest or Pandects of Justinian, because in it were digested, or put in order in a general collection, the best decisions of the courts, and the opinions and treatises of the ablest lawyers. All previous codes were ransacked, and two thousand volumes of legal argument condensed; and in three years the indefatigable law-reformers published their work, wherein three million leading judgments were reduced to a hundred and fifty thousand. Future confusion was guarded against by a commandment of the emperor abolishing all previous laws and making it penal to add note or comment to the collection now completed. The sentences delivered by the emperor, after the appearance of the Pandects, were published under the name of the Novellæ; and with this great clearing-out of the Augean stable of ancient law, the salutary labours of Trebonian came to a close. In those laws are to be seen both the virtues and the vices of their origin. They sprang from the wise liberality of a despot, and handle the rights of subjects, in their relation to each other, with the equanimity and justice of a power immeasurably raised above them all. But the unlimited supremacy of the ruler is maintained as the sole foundation for the laws themselves. So we see in these collections, and in the spirit which they have spread over all the codes which have taken them for their model, a combination of humanity and probity in the civil law, with a tendency to exalt to a ridiculous excess the authority of the governing power.

This has been a century of wonderful revolutions. We have seen the kingdom of the Ostrogoths take the lead in Europe under the wise government of Theodoric the Great. We have seen it overthrown by an army of very small size, consisting of the very forces they had so recently triumphed over in every battle; and finally, after the victories over them of Belisarius and Narses, we have seen the last small remnant of their name removed from Italy altogether and eradicated from history for all future time. But, strange as this reassertion of the Greek supremacy was, the rapidity of its overthrow was stranger still. A new people came upon the stage, and established the Lombard power. The empire contracted itself within its former narrow bounds, and kept up the phantom of its superiority merely by the residence of an Exarch, or provincial governor, at Ravenna. The fiction of its power was further maintained by the Emperor’s official recognition of certain rulers, and his ratification of the election of the Roman bishops. But in all essentials the influence had departed from Constantinople, and the Western monarchies were separated from the East.

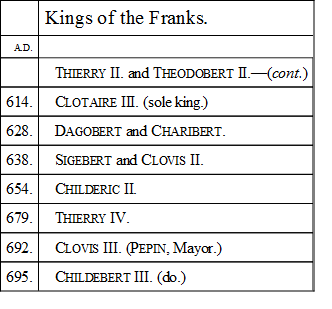

In the Northwest, the confederacy of the Franks, which had consolidated into one immense and powerful kingdom under Clovis, became separated, weakened, and converted into open enemies under his degenerate successors.

But as the century drew to a close, a circumstance occurred, far away from the scene of all these proceedings, which had a greater influence on human affairs than the reconquest of Italy or the establishment of France. This was the marriage of a young man in a town of Arabia with the widow of his former master. In 564 this young man was born in Mecca, where his family had long held the high office of custodiers and guardians of the famous Caaba, which was popularly believed to be the stone that covered the grave of Abraham. But when he was still a child his father died, and he was left to the care of his uncle. The simplicity of the Arab character is shown in the way in which the young noble was brought up. Abu Taleb initiated him in the science of war and the mysteries of commerce. He managed his horse and sword like an accomplished cavalier, and followed the caravan as a merchant through the desert. Gifted with a high poetical temperament, and soaring above the grovelling superstitions of the people surrounding him, he used to retire to meditate on the great questions of man’s relation to his Maker, which the inquiring mind can never avoid. Meditation led to excitement. He saw visions and dreamed dreams. He saw great things before him, if he could become the leader and lawgiver of his race. But he was poor and unknown. His mistress Cadijah saw the aspirations of her noble servant, and offered him her hand. He was now at leisure to mature the schemes of national regeneration and religious improvement which had occupied him so long, and devoted himself more than ever to study and contemplation. This was Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam, who retired in 594 to perfect his scheme, and whose empire, before many years elapsed, extended from India to Spain, and menaced Christianity and Europe at the same time from the Pyrenees and the Danube.

SEVENTH CENTURY

Nennius, (620,) Bede, (674-735,) Aldhelm, Adamnanus.

THE SEVENTH CENTURY

POWER OF ROME SUPPORTED BY THE MONKS – CONQUESTS OF THE MOHAMMEDANSThis, then, is the century during which Mohammedanism and Christianity were marshalling their forces—unknown, indeed, to each other, but preparing, according to their respective powers, for the period when they were to be brought face to face. We shall go eastward, and follow the triumphant march of the warriors of the Crescent from Arabia to the shores of Africa; but first we shall cast a desponding eye on the condition and prospects of the kingdoms of the West. Conquest, spoliation, and insecurity had done their work. Wave after wave had passed over the surface of the old Roman State, and obliterated almost all the landmarks of the ancient time. The towns, to be sure, still remained, but stripped of their old magnificence, and thinly peopled by the dispossessed inhabitants of the soil, who congregated together for mutual support. Trade was carried on, but subject to the exactions, and sometimes the open robberies, of the avaricious chieftains who had reared their fortresses on the neighbouring heights. Large tracts of country lay waste and desolate, or were left to the happy fertility of nature in the growth of spontaneous woods. Marshes were formed over whole districts, and the cattle picked up an uncertain existence by browsing over great expanses of poor and unenclosed land. These flocks and herds were guarded by hordes of armed serfs, who camped beside them on the fields, and led a life not unlike that of their remote ancestors on the steppes of Tartary. A man’s wealth was counted by his retainers, and there was no supreme authority to keep the dignitaries, even of the same tribe, from warring on each other and wasting their rival’s country with fire and sword. Agriculture, therefore, was in the lowest state, and famines, plagues, and other concomitants of want were common in all parts of Europe. One beautiful exception must be made to this universal neglect of agriculture, in favour of the Benedictine monks, established in various parts of Italy and Gaul in the course of the preceding century. Religious reverence was a surer safeguard to those lowly men than castles or armour could have been. No marauder dared to trespass on lands which were under the protection of priest and bishop. And these Western recluses, far from imitating the slothful uselessness of the Eastern monks, turned their whole attention to the cultivation of the soil. In this they bestowed a double benefit on their fellow-men, for, in addition to the positive improvement of the land, they rescued labour from the opprobrium into which it had fallen, and raised it to the dignity of a religious duty. Slavery, we have seen, was universally practised in all the conquered territories, and as only the slaves were compelled to the drudgeries of the field, the work itself borrowed a large portion of the degradation of the unhappy beings condemned to it; and robbery, pillage, murder, and every crime, were considered far less derogatory to the dignity of free Frank or Burgundian than the slightest touch of the mattock or spade. How surprised, then, were the haughty countrymen and descendants of Clovis or Alboin to see the revered hands from which they believed the highest blessings of Heaven to flow, employed in the daily labour of digging, planting, sowing, reaping, thrashing, grinding, and baking! At first they looked incredulously on. Even the monks were disposed to consider it no part of their conventual duties. But the founder of their institution wrote to them, “to beware of idleness, as the greatest enemy of the soul,” and not to be uneasy if at any time the cares of the harvest hindered them from their formal readings and regulated prayers. “No person is ever more usefully employed than when working with his hands or following the plough, providing food for the use of man.” And the effects of these exhortations were rapidly seen. Wherever a monastery was placed, there were soon fertile fields all round it, and innumerable stacks of corn. Generally chosen with a view to agricultural pursuits, we find sites of abbeys at the present day which are the perfect ideal of a working farm; for long after the outburst of agricultural energy had expired among the monks of St. Benedict, the choice of situation and knowledge of different soils descended to the other ecclesiastical establishments, and skill in agriculture continued at all times a characteristic of the religious orders. What could be more enchanting than the position of their monastic homes? Placed on the bank of some beautiful river, surrounded on all sides by the low flat lands enriched by the neighbouring waters, and protected by swelling hills where cattle are easily fed, we are too much in the habit of attributing the selection of so admirable a situation to the selfishness of the portly abbot. When the traveller has admired the graces of Melrose or of Tintern—the description applies equally to almost all the foundations of an early date—and has paid due attention to the chasteness of the architecture, and beauty of “the long-resounding aisle and fretted vault,” he sometimes contemplates with a sneer the matchless charm of the scenery, and exceeding richness of the haugh or strath in which the building stands. “Ah,” he says, “they were knowing old gentlemen, those monks and priors. They had fish in the river, fat beeves upon the meadow, red-deer on the hill, ripe corn on the water-side, a full grange at Christmas, and snowy sheep at midsummer.” And so they had, and deserved them all. The head of that great establishment was not wallowing in the fat of the land to the exclusion of envious baron or starving churl. He was, in fact, setting them an example which it would have been wise in them to follow. He merely chose the situation most fitted for his purpose, and bestowed his care on the lands which most readily yielded him his reward. It was not necessary for the monks in those days to seek out some neglected corner, and to restore it to cultivation, as an exercise of their ingenuity and strength. They were free to choose from one end of Europe to the other, for the whole of it lay useless and comparatively barren. But when these able-bodied recluses, if such they may be called, had shown the results of patient industry and skill, the peasants, who had seen their labours, or occasionally been employed to assist them, were able to convey to their lay proprietors or masters the lessons they had received. And at last something venerable was thought to reside in the act of farming itself. It was so uniformly found an accompaniment of the priestly character, that it acquired a portion of its sanctity, and the rude Lombard or half-civilized Frank looked with a kind of awe upon waving corn and rich clover, as if they were the result of a higher intelligence and purer life than he possessed. Even the highest officers in the Church were expected to attend to these agricultural conquests. In this century we find, that when kings summoned bishops to a council, or an archbishop called his brethren to a conference, care was taken to fix the time of meeting at a season which did not interfere with the labours of the farm. Privileges naturally followed these beneficial labours. The kings, in their wondering gratitude, surrounded the monasteries with fresh defences against the envy or enmity of the neighbouring chiefs. Their lands became places of sanctuary, as the altar of the Church had been. Freedmen—that is, persons manumitted from slavery, but not yet endowed with property—were everywhere put under the protection of the clergy. Immunities were heaped upon them, and methods found out of making them a separate and superior race. At the Council of Paris, in 613, it was decreed that the priest who offended against the common law should be tried by a mixed court of priests and laymen. But soon this law, apparently so just, was not considered enough, and the trial of ecclesiastics was given over to the ecclesiastical tribunals, without the admixture of the civil element. Other advantages followed from time to time. The Church was found in all the kingdoms to be so useful as the introducer of agriculture, and the preserver of what learning had survived the Roman overthrow, that the ambitious hierarchy profited by the royal and popular favour. They were the most influential, or perhaps it would be more just to say they were the only, order in the State. There was a nobility, but it was jarring and disunited; there were citizens, but they were powerless and depressed; there was a king, but he was but the first of the peers, and stood in dignified isolation where he was not subordinate to a combination of the others. The clergy, therefore, had no enemy or rival to dread, for they had all the constituents of power which the other portions of the population wanted. Their property was more secure; their lands were better cultivated; they were exempt from many of the dangers and burdens to which the lay barons were exposed; they were not liable to the risks and losses of private war; they had more intelligence than their neighbours, and could summon assistance, either in advice, or support, or money, from the farthest extremity of Europe. Nothing, indeed, added more, at the commencement of this century, to the authority of those great ecclesiastical chieftains, than the circumstance that their interests were supported, not only by their neighbouring brethren, but by mitred abbot and lordly bishop in distant lands. If a prior or his monks found themselves ill used on the banks of the Seine, their cause was taken up by all other monks and priors wherever they were placed. And the rapidity of their intercommunication was extraordinary. Each monastery seems to have had a number of active young brethren who traversed the wildest regions with letters or messages, and brought back replies, almost with the speed and regularity of an established post. A convent on Lebanon was informed in a very short time of what had happened in Provence—the letter from the Western abbot was read and deliberated on, and an answer intrusted to the messenger, who again travelled over the immense tract lying between, receiving hospitality at the different religious establishments that occurred upon his way, and everywhere treated with the kindness of a brother. Monasteries in this way became the centres of news as well as of learning, and for many hundred years the only people who knew any thing of the state of feeling in foreign nations, or had a glimpse of the mutual interests of distant kingdoms, were the cowled and gowned individuals who were supposed to have given up the world and to be totally immersed in penances and prayers. What could Hereweg of the strong hand do against a bishop or abbot, who could tell at any hour what were the political designs of conquerors or kings in countries which the astonished warrior did not know even by name; who retained by traditionary transmission the politeness of manner and elegance of accomplishment which had characterized the best period of the Roman power, when Christianized noblemen, on being promoted to an episcopal see, had retained the delicacies of their former life, and wrote love-songs as graceful as those of Catullus, and epigrams neither so witty nor so coarse as those of Martial? Intelligence asserted its superiority over brute force, and in this century the supremacy of the Church received its accomplishment in spite of the depravation of its principles. It gained in power and sank in morals. A hundred years of its beneficial action had made it so popular and so powerful that it fell into temptations, from which poverty or unpopularity would have kept it free. The sixth century was the period of its silent services, its lower officers endearing themselves by useful labour, and its dignitaries distinguishing themselves by learning and zeal. In the seventh century the fruit of all those virtues was to be gathered by very different hands. Ambitious contests began between the different orders composing the gradually rising hierarchy, from the monk in his cell to the Bishop of Rome or Constantinople on their pontifical thrones. It is very sad, after the view we have taken of the early benefits bestowed on many nations by the labours and example of the priests and monks, to see in the period we have reached the total cessation of life and energy in the Church;—of life and energy, we ought to say, in the fulfilment of its duties; for there was no want of those qualities in the gratification of its ambition. Forgetful of what Gregory had pronounced the chief sign of Antichrist, when he opposed the pretension of his rival metropolitan to call himself Universal Bishop, the Bishops of Rome were deterred by no considerations of humility or religion from establishing their temporal power. Up to this time they had humbly received the ratification of their election from the Emperors of the East, whose subjects they still remained. But the seat of their empire was far off, their power was a tradition of the past, and great thoughts came into the hearts of the spiritual chiefs, of inroads on the territory of the temporal rulers. In this design they looked round for supporters and allies, and with a still more watchful eye on the quarters from which opposition was to be feared. The bishops as a body had fallen not only into contempt but hatred. One century had sufficed to extinguish the elegant scholarship I have mentioned, at one time characteristic of the Christian prelates. Ignorance had become the badge of all the governors of the Church—ignorance and debauchery, and a tyrannical oppression of their inferiors. The wise old man in Rome saw what advantage he might derive from this, and took the monks under his peculiar protection, relieved them from the supervision of the local bishop, and made them immediately dependent on himself. By this one stroke he gained the unflinching support of the most influential body in Europe. Wherever they went they held forth the Pope as the first of earthly powers, and began already, in the enthusiasm of their gratitude, to speak of him as something more than mortal. To this the illiterate preachers and prelates had nothing to reply. They were sunk either in the grossest darkness, or involved in the wildest schemes of ambition, bishoprics being even held by laymen, and by both priest and laymen used as instruments of advancement and wealth. From these the Pontiff on the Tiber, whose weaknesses and vices were unknown, and who was held up for invidious contrast with the bishops of their acquaintance by the libellous and grateful monks, had nothing to fear. He looked to another quarter in the political sky, and perceived with satisfaction that the kingly office also had fallen into contempt. Having lost the first impulse which carried it triumphantly over the dismembered Roman world, and made it a tower of strength in the hands of warriors like Theodoric the Goth and Clovis the Frank, it had forfeited its influence altogether in the pitiful keeping of the bloodthirsty or do-nothing kings who had submitted to the tutelage of the Mayors of the Palace.