полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

But Rome, spared by the influence of the bishop from the ravage of the Huns, could not escape the destroying enmity of Genseric and the Vandals. Dashing across from Africa, these furious conquerors destroyed for destruction’s sake, and affixed the name of Vandalism on whatever is harsh and unrefined. For fourteen days the spoilers were at work in Rome, and it is only wonderful that after so many plunderings any thing worth plundering remained. When the sated Vandals crossed to Carthage again, the Gothic and Suevic kings gave the purple to whatever puppet they chose. Afraid still to invest themselves with the insignia of the Imperial power, they bestowed them or took them away, and at last rendered the throne and the crown so contemptible, that when Odoacer was proclaimed King of Italy, the phantom assembly which still called itself the Roman Senate sent back to Constantinople the tiara and purple robe, in sign that the Western Empire had passed away. Zeno, the Eastern ruler, retained the ornaments of the departed sovereignty, and sent to the Herulean Odoacer the title of “Patrician,” sole emblem left of the greatness and antiquity of the Roman name. It may be interesting to remember that the last who wore the Imperial crown was a youth who would probably have escaped the recognition of posterity altogether, if he had not, by a sort of cruel mockery of his misfortunes, borne the names of Romulus Augustulus—the former recalling the great founder of the city, and the latter the first of the Imperial line.

Thus, then, in 476, Rome came to her deserved and terrible end; and before we trace the influence of this great event upon the succeeding centuries, it will be worth while to devote a few words to the cause of its overthrow. These were evidently three—the ineradicable barbarity and selfishness of the Roman character, the depravation of manners in the capital, and the want of some combining influence to bind all the parts of the various empire into a whole. From the earliest incidents in the history of Rome, we gather that she was utterly regardless of human life or suffering. Her treatment of her vanquished enemies, and her laws upon parental authority, upon slaves and debtors, show the pitiless disposition of her people. Look at her citizens at any period of her career—her populace or her consuls—in the field of battle or in the forum, you will always find them the true descendants of those blood-stained refugees, who established their den of robbers on the seven hills, and pretended they were led by a man who had been suckled by a wolf. While conquest was their object, this sanguinary disposition enabled them to perform great exploits; but when victory had secured to them the blessings of peace and safety, the same thirst for excitement continued. They cried out for blood in the amphitheatre, and had no pleasure in any display which was not accompanied with pain. The rival chief who had perilled their supremacy in the field was led in ferocious triumph at the wheel of his conqueror, and beheaded or flogged to death at the gate of the Capitol. The wounded gladiator looked round the benches of the arena in hopes of seeing the thumbs of the spectators turned down—the signal for his life being spared; but matrons and maids, the high and the low, looked with unmoved faces upon his agonies, and gave the signal for his death without remorse. They were the same people, even in their amusements, who gave order for the destruction of Numantium and Carthage. But cruelty was not enough. They sank into the wildest vices of sensuality, and lost the dignity of manhood, and the last feelings of self-respect. Never was a nation so easily habituated to slavery. They licked the hand that struck them hardest. They hung garlands for a long time on the tomb of Nero. They insisted on being revenged on the murderers of Commodus, and frequently slew more citizens in broils in the street and quarrels in the theatre, than had fought at Cannæ or Zama. It might have been hoped that the cruelty which characterized the days of their military aggression would be softened down when they had become the acknowledged rulers of the world. Luxury itself, it might be thought, would be inconsistent with the sight of blood. But in this utterly detestable race the two extremes of human society seemed to have the same result. The brutal, half-clothed savage of an early age conveyed his tastes as well as his conquests to the enervated voluptuary of the empire. The virtues, such as they were, of that former period—contempt of danger, unfaltering resolution, and a certain simplicity of life—had departed, and all the bad features were exaggerated. Religion also had disappeared. Even a false religion, if sincerely entertained, is a bond of union among all who profess its faith. But between Rome and its colonies, and between man and man, there was soon no community of belief. The sweltering wretches in the Forum sneered at the existence of Bacchus in the midst of his mysteries, and imitated the actions of their gods, while they laughed at the hypocrisy of priests and augurs, who treated them as divine. A cruel, depraved, godless people—these were the Romans who had enslaved the world with their arms and corrupted it with their civilization. When their capital fell, men felt relieved from a burden and shame. The lessons of Christianity had been thrown away on a population too gross and too truculent to receive them. Some of gentler mould than others had received the Saviour; but to the mass of Romans the language of peace and justice, of forgiveness and brotherhood, was unknown. It was to be the worthier recipients of a pure and elevating faith, that the Goth was called from his wilderness and the German from his forest.

But the faith had to be purified itself before it was fitted for the reception of the new conquerors of the world. The dissensions of the Christian Churches had added only a fresh element of weakness to the empire of Rome. There were heretics everywhere, supporting their opinions with bigotry and violence—Arians, Sabellians, Montanists, and fifty names besides. Torn by these parties, dishonoured by pretended conversions, the result of flattery and ambition, the Christian Church was further weakened by the effect of wealth and luxury upon its chiefs. While contending with rival sects upon some point of discipline or doctrine, they made themselves so notorious for the desire of riches, and the infamous arts they practised to get themselves appointed heirs of the rich members of their congregations, that a law was passed making a conveyance in favour of a priest invalid. And it is not from Pagan enemies or heretical rivals we learn this—it is from the letters still extant of the most honoured Fathers of the Church. One of them tells us that the Prefect Pretextatus, alluding to the luxury of the Pontiffs, and to the magnificence of their apparel, said to Pope Damasus, “Make me Bishop of Rome, and I will turn Christian.” “Far, then,” says a Roman Catholic historian of our own day, “from strengthening the Roman world with its virtues, the Christian society seemed to have adopted the vices it was its office to overcome.” But the fall of Roman power was the resurrection of Christianity. It had a Resurrection, because it had had a Death, and a new world was now prepared for its reception. Its everlasting truths, indeed, had been full of life and vigour all through the sad period of Roman depravation, but the ground was unfitted for their growth; and the great characteristic of this century is not the conquest of Rome by Alaric the Goth, or the dreadful assault on Europe by Attila the Hun, or the final abolition of the old capital of the world by Odoacer the Herulean, but rather the ecclesiastical chaos which spread over the earth. The age of martyrs had passed—the philosophers had begun their pestiferous tamperings with the facts of revelation—and over all rioted and stormed an ambitious and worldly priesthood, who hated their opponents with more bitterness than the heathens had displayed against the Christians, and ran wild in every species of lawlessness and vice. The deserts and caves which used to give retreat to meditative worshippers or timid believers, now teemed with thousands of furious and fanatical monks, who rushed occasionally into the great cities of the empire, and filled their streets with blood and rapine. Guided by no less fanatical bishops, they spread murder and terror over whole provinces. Alexandria stood in more fear of these professed recluses than of an army of hostile soldiers. “There is a race,” says Eunapius, “called monks—men indeed in form, but hogs in life, who practise and allow abominable things. Whoever wears a black robe, and is not ashamed of filthy garments, and presents a dirty face to the public view, obtains a tyrannical authority.” False miracles, absurd prophecies, and ludicrous visions were the instruments with which these and other impostors established their power. Mad enthusiasts imprisoned themselves in dungeons, or exposed themselves on the tops of pillars, naked, except by the growth of their tangled hair, and the coating of filth upon their persons,—and gained credit among the ignorant for self-denial and abnegation of the world.

All the high offices of the Church were so lucrative and honourable as to be the object of universal desire.

To be established archbishop of a diocese cost more lives than the conquest of a province. When the Christian community needed support from without, they had recourse to some rich or powerful individual, some general of an army, or governor of a district, and begged him to assume the pastoral staff in exchange for his military sword. Sometimes the assembled crowd cried out the name of a favourite who was not even known to be a Christian, and the mitre was conveyed by acclamation to a person who had to undergo the ceremonies of baptism and ordination before he could place it on his head. Sometimes the exigencies of the congregation required a scholar or an orator for its head. It applied to a philosopher to undertake its direction. He objected that his philosophy had been declared inconsistent with the Christian faith, and his mode of life contrary to Christian precept. They forgave him his philosophy, his horses and hounds, his wife and children, and constituted him their chief. Age was of no consequence. A youth of eighteen has been saluted bishop by a cry which seemed to the multitude the direct inspiration of Heaven, and seated in the chair of his dignity almost without his knowledge. Once established on his episcopal seat, he had no superior. The Roman Bishop had not yet asserted his supremacy over the Church. Each prelate was sovereign Pontiff of his own see, and his doctrines for a long time regulated the doctrines of his flock. Under former bishops, Milan had been Arian, under Ambrose it was orthodox, and with a change of master might have been Arian again. The emperors had occasionally interfered with their authoritative decisions, but generally the dispute was left in divided dioceses to be settled by argument, when the rivals’ tempers allowed such a mode of warfare, but more frequently by armed bands of the retainers of the respective creeds, and sometimes by an appeal to miracles. But with this century a new spirit of bitterness was let loose upon the Church. Councils were held, at which the doctrines of the minority were declared dangerous to the State, and the civil power was invoked to carry the sentence into effect. In Africa, where the great name of Augustin of Hippo admitted no opposition, the Donatists, though represented by no less than two hundred and seventy-nine prelates, were condemned as heretics, and given over to the persecuting sword. But in other quarters the dissidents looked for support to the civil power, when it happened to be of their opinion in Church affairs. Rome chose Clovis, the politic and energetic Frank, for its guardian and protector, and the Arians threw themselves in the same way on the support of the Visigoths and Burgundians. A difference of faith became a pretext for war. Clovis, who envied his neighbours their territories south of the Loire, led an expedition against them, crying, “It is shameful to see those Arians in possession of such goodly lands!” and everywhere a vast activity was perceptible in the Church, because its interests were now connected with those of kings and peoples. In earlier times, discussions were carried on on a great variety of doctrines which, though widely spread, were not yet authoritatively declared to be articles of faith. St. Jerome himself, and others, had had to defend their opinions against the attacks of various adversaries, who, without ceasing to be considered true members of the Church, wrote powerfully against the worship of martyrs and their relics; against the miracles professedly wrought at their tombs; against fasting, austerities, and celibacy. No appeal was made on those occasions either to the Bishop of Rome as head of the Church, or to the emperor as head of the State. Now, however, the spirit of moderation was banished, and the decrees of councils were considered superior to private or even diocesan judgment. Life and freedom of discussion were at an end under an enforced and rigid uniformity. But the struggle lasted through the century. It was the period of great convulsions in the State, and disputations, wranglings, and struggle in the Church. How these, in a State tortured by perpetual change, and a Church filled with energy and fire, acted upon each other, may easily be supposed. The doubtful and unsteady civil government had subordinated itself to the turbulent ardour of the perplexed but highly-animated Church. After the conquest of Rome, where was the barbaric conqueror to look for any guide to internal unity, or any relic of the vanished empire by which to connect himself with the past? There was only the Church, which was now not only the professed teacher of obedience, peace, and holiness, but the only undestroyed institution of the State. The old population of Rome had been wasted by the sword, and famine, and deportation. The emperors of the West had left the scene; the Roman Senate was no more. There was but one authority which had any influence on the wretched crowd who had returned to their ancient capital, or sought refuge in its ruined palaces or grass-grown streets from the pursuit of their foes; and that was the Bishop of the Christian congregation—whose palace had been given to him by Constantine—who claimed already the inheritance of St. Peter—and who carried to the new government either the support of a willing people, or the enmity of a seditious mob.

|A.D. 489.|

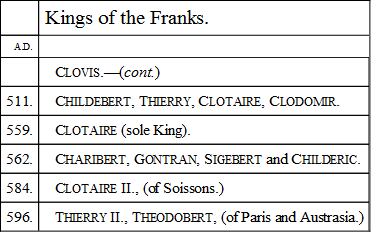

A new hero came upon the scene in the person of Theodoric, the Ostrogoth. Odoacer tried in vain to resist the two hundred thousand warriors of this tribe who poured upon Italy in 490, and, after a long resistance in Ravenna, yielded the kingdom of Italy to his rival. Theodoric, though an Arian, cultivated the good opinion of the orthodox, and gained the favour of the Roman Bishop. He had almost a superstitious veneration for the dignities of ancient Rome. He treated with respect an assembly which called itself the Senate, but did not allow his love of antiquity to blind him to the degeneracy of the present race. He interdicted arms to all men of Roman blood, and tried in vain to prevent his followers from using the appellation “Roman” as their bitterest form of contempt. Lands were distributed to his followers, and they occupied and improved a full third of Italy. Equal laws were provided for both populations, but he forbade the toga and the schools to his countrymen, and left the studies and refinements of life, and offices of civil dignity, to the native race. The hand that holds the pen, he said, becomes unfitted for the sword. But, barbarian as he was called, he restored the prosperity which the fairest region of the earth had lost under the emperors. Bridges, aqueducts, theatres, baths, were repaired; palaces and churches built. Agriculture was encouraged, attempts were made to drain the Pontine Marshes; iron-mines were worked in Dalmatia, and gold-mines in Bruttium. Large fleets protected the coasts of the Mediterranean from pirates and invaders. Population increased, taxes were diminished; and a ruler who could neither read nor write attracted to his court all the learned men of his time. Already the energy of a new and enterprising people was felt to the extremities of his dominions. A new race, also, was established in Gaul. Klodwig, leader of the Franks, received baptism at the hands of St. Remi in 496, and began the great line of French rulers, who, passing his name through the softened sound of Clovis, presented, in the different families who succeeded him, eighteen kings of the name of Louis, as if commemorative of the founder of the monarchy.

In England the petty kingdoms of the Heptarchy were in the course of formation, and though, when viewed closely, we seemed a divided and even hostile collection of individual tribes, the historian combines the separate elements, and tells us that, before the fifth century expired, another branch of the barbarians had settled into form and order, and that the Anglo-Saxon race had taken possession of its place.

With these newly-founded States rising with fresh vigour from among the decayed and festering remains of an older society, we look hopefully forward to what the future years will show us.

SIXTH CENTURY

Boethius, Procopius, Gildas, Gregory of Tours, Columba, (520-597,) Priscian, Columbanus, Benedict, Evagrius, (Scholasticus,) Fulgentius, Gregory the Great.

THE SIXTH CENTURY

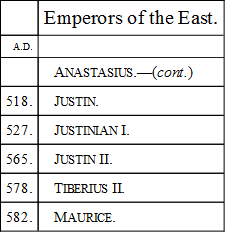

BELISARIUS AND NARSES IN ITALY – SETTLEMENT OF THE LOMBARDS – LAWS OF JUSTINIAN – BIRTH OF MOHAMMEDTheodoric, though not laying claim to universal empire in right of his possession of Rome and Italy, exercised a sort of supremacy over his contemporaries by his wisdom and power. He also strengthened his position by family alliances. His wife was sister of Klodwig or Clovis, King of the Franks. He married his own sister to Hunric, King of the Vandals, his niece to the Thuringian king. One of his daughters he gave to Sigismund, King of the Burgundians, and the other to Alaric the Second, King of the Visigoths. Relying on the double influence which his relationship and reputation secured to him, he rebuked or praised the potentates of Europe as if they had been his children, and gave them advice in the various exigencies of their affairs, to which they implicitly submitted. He would fain have kept alive what was left of the old Roman civilization, and heaped honours on the Senator Cassiodorus, one of the last writers of Rome. “We send you this man as ambassador,” he said to the King of the Burgundians, “that your people may no longer pretend to be our equals when they perceive what manner of men we have among us.” But his rule, though generous, was strict. He imprisoned the Bishop of Rome for disobedience of orders in a commission he had given him, and repressed discontent and the quarrels of the factions with an unsparing hand. But the death of this great and wise sovereign showed on what unstable foundations a barbaric power is built. Frightful tragedies were enacted in his family. His daughter was murdered by her nephew, whom she had associated with her in the guardianship of her son. But vengeance overtook the wrong-doer, and a strange revolution occurred in the history of the world. The emperor reigning at Constantinople was the celebrated Justinian. He saw into what a confused condition the affairs of the new conquerors of Italy had fallen. Rallying round him all the recollections of the past—giving command of his armies to one of the great men who start up unexpectedly in the most hopeless periods of history, whose name, Belisarius, still continues to be familiar to our ears—and rousing the hostile nationalities to come to his aid, he poured into the peninsula an army with Roman discipline and the union which community of interests affords. |A.D. 535.|In a remarkably short space of time, Belisarius achieved the conquest of Italy. The opposing soldiers threw down their arms at sight of the well-remembered eagles. The nations threw off the supremacy of the Ostrogoths. Belisarius had already overthrown the kingdom of the Vandals and restored Africa to the empire of the East. He took Naples, and put the inhabitants to the sword. He advanced upon Rome, which the Goths deserted at his approach. The walls of the great city were restored, and a victory over the fugitives at Perugia seemed to secure the whole land to its ancient masters. But Witig, the Ostrogoth, gathered courage from despair. He besought assistance from the Franks, who had now taken possession of Burgundy; and volunteers from all quarters flocked to his standard, for he had promised them the spoils of Milan. Milan was immensely rich, and had espoused the orthodox faith. The assailants were Arians, and intent on plunder. Such destruction had scarcely been seen since the memorable slaughter of the Huns at Châlons on the Marne. The Ostrogoths and Burgundian Franks broke into the town, and the streets were piled up with the corpses of all the inhabitants. There were three hundred thousand put to death, and multitudes had died of famine and disease. The ferocity was useless, and Belisarius was already on the march; Witig was conquered, in open fight, while he was busy besieging Rome; Ravenna itself, his capital, was taken, and the Ostrogothic king was led in triumph along the streets of Constantinople.

|A.D. 540.|

But the conqueror of the Ostrogoths fell into disfavour at court. He was summoned home, and a great man, whom his presence in Italy had kept in check, availed himself of his absence. Totila seemed indeed worthy to succeed to the empire of his countryman Theodoric. He again peopled the utterly exhausted Rome; he restored its buildings, and lived among the new-comers himself, encouraging their efforts to give it once more the appearance of the capital of the world. But these efforts were in vain. There was no possibility of reviving the old fiction of the identity of the freshly-imported inhabitants and the countrymen of Scipio and Cæsar. Only one link was possible between the old state of things and the new. It was strange that it was left for the Christian Bishop to bridge over the chasm that separated the Rome of the Consulship and the Empire from the capital of the Goths. Yet so it was. While the short duration of the reigns of the barbaric kings prevented the most sanguine from looking forward to the stability of any power for the future, the immunity already granted to the clerical order, and the sanctuary afforded, in the midst of the wildest excesses of siege and storm, by their shrines and churches, had affixed a character of inviolability and permanence to the influence of the ecclesiastical chief. At Constantinople, the presence of the sovereign, who affected a grandeur to which the pretensions to divinity of the Roman emperors had been modesty and simplicity, kept the dignity of the Bishop in a very secondary place. But at Rome there was no one left to dispute his rank. His office claimed a duration of upwards of four hundred years; and though at first his predecessors had been fugitives and martyrs, and even now his power had no foundation except in the willing obedience of the members of his flock, the necessity of his position had forced him to extend his claims beyond the mere requirements of his spiritual rule. During the ephemeral occupations of the city by Vandals and Huns and Ostrogoths, and all the tribes who successively took possession of the great capital, he had been recognised as the representative of the most influential portion of the inhabitants. As it naturally followed that the higher the rank of a ruler or intercessor was, the more likely his success would be, the Christians of the orthodox persuasion had the wisdom to raise their Bishop as high as they could. He had stood between the devoted city and the Huns; he had promised obedience or threatened resistance to the Goths, according to the conduct pursued with regard to his flock by the conquerors. He had also lent to Belisarius all the weight of his authority in restoring the power of the emperors, and from this time the Bishop of Rome became a great civil as well as ecclesiastical officer. All parties in turn united in trying to win him over to their cause—the Arian kings, by kindness and forbearance to his adherents; and the orthodox, by increasing the rights and privileges of his see. And already the policy of the Roman Pontiffs began to take the path it has never deserted since. They looked out in all quarters for assistance in their schemes of ambition and conquest. Emissaries were despatched into many nations to convert them, not from heathenism to Christianity, but from independence to an acknowledgment of their subjection to Rome. It was seen already that a great spiritual empire might be founded upon the ruins of the old Roman world, and spread itself over the perplexed and unstable politics of the barbaric tribes. No means, accordingly, were left untried to extend the conquests of the spiritual Cæsar. When Clovis the Frank was converted by the entreaties of his wife from Arianism to the creed of the Roman Church, the orthodox bishops of France considered it a victory over their enemies, though these enemies were their countrymen and neighbours. And from henceforth we find the different confessions of faith to have more influence in the setting up or overthrowing of kingdoms than the strength of armies or the skill of generals. Narses, who was appointed the successor of Belisarius, was a believer in the decrees of the Council of Nice. His orthodoxy won him the support of all the orthodox Huns and Heruleans and Lombards, who formed an army of infuriated missionaries rather than of soldiers, and gained to his cause the majority of the Ostrogoths whom it was his task to fight. Totila in vain tried to bear up against this invasion. The heretical Ostrogoths, expelled from the towns by their orthodox fellow-citizens, and ill supported by the inhabitants of the lands they traversed, were defeated in several battles; and at last, when the resisting forces were reduced to the paltry number of seven thousand men, their spirits broken by defeat, and a continuance in Italy made useless by the hostile feelings of the population, they applied to Narses for some means of saving their lives. He furnished them with vessels, which carried them from the lands which, sixty years before, had been assigned them by the great Theodoric, and they found an obscure termination to so strange and checkered a career, by being lost and mingled in the crowded populations of Constantinople. This was in 553. The Ostrogoths disappear from history. The Visigoths have still a settlement at the southwest of France and in the rich regions of Spain, but they are isolated by their position, and are divided into different branches. The Franks are a great and seemingly well-cemented race between the Rhine and the sea. The Burgundians have a form of government and code of laws which keep them distinct and powerful. There are nations rising into independence in Germany. In England, Christianity has formed a bond which practically gives firmness and unity to the kingdoms of the Heptarchy; and it might be expected that, having seen so many tribes of strange and varying aspect emerge from the unknown regions of the East, we should have little to do but watch the gradual enlightenment of those various races, and see them assuming, by slow degrees, their present respective places; but the undiscovered extremities of the earth were again to pour forth a swarm of invaders, who plunged Italy back into its old state of barbarism and oppression, and established a new people in the midst of its already confused and intermixed populations.