Полная версия

The Birth of Modern Britain: A Journey into Britain’s Archaeological Past: 1550 to the Present

These projects involved the digging of numerous channels to carry water from a main cut, usually alongside a natural river, and from there into a series of subsidiary streams carefully positioned to distribute it evenly across the meadow. These flooded meadows could be extensive, covering many acres, and their construction also involved the erection of numerous sluice gates which had to be opened and closed in a specific order, depending on what was needed. In fact the actual business of operating and maintaining water meadows required labour, plus considerable skill and experience, which might help explain why they failed to thrive after the opulent period known as Victorian high farming (which I’ll explain later) was brought to an end by the great agricultural depression of the 1870s.28

Ultimately water meadows were intended to extend the initial flush of spring and early summer grass, both through simple watering and by the laying down of a very thin layer of flood-clay (alluvium) which provided early season nourishment to the growing grass. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and well into the nineteenth, water meadows made the keeping of sheep and the growing of corn on the chalk downlands of Wessex and southern England such a profitable business. This is because the rather thin grass cover of the chalk downs doesn’t really start growing in earnest until May, so the new water meadows on the richer soils of the valley bottoms meant that abundant grazing was now available in March and April, when stocks of hay were nearly exhausted. Almost as important, it also meant that the arable parts of the farm now had an even more plentiful supply of 29 manure.

There is now a general consensus that the concept of a short-lived and as such truly revolutionary period of agricultural ‘improvement’ is mistaken and instead we should be thinking of a more extended era of ‘improvement’, from, say, 1500 to 1850. And many, myself included, would reckon that such a length of time – some 350 years – was more evolutionary than revolutionary.30 It’s roughly the same length of time that separates the present from the execution of King Charles I. With all of this in mind, I prefer to refer to the period as the era of agricultural development – because it could be argued that, with hindsight, some of the so-called ‘improvements’ were actually nothing of the sort.31

Whatever one’s definition of the period, the changes I have just been discussing are generally seen to have been the result of pioneering work carried out by enlightened, reform-minded, high-profile individuals, who are usually lumped together under the general heading of agricultural ‘Improvers’. Jethro Tull, largely I suspect because of the 1970s rock band named after him, is the best known of these ‘Improvers’. I remember being taught at school that he invented the seed drill, whereas in reality he urged its adoption and was a great believer in it. He didn’t actually invent it. Other important ‘Improvers’ were the 1st Earl of Leicester, Thomas William Coke (1754–1842) of Holkham Hall, Norfolk (known at the time as ‘Coke of Norfolk’), and the Whig Cabinet Minister Charles ‘Turnip’ Townshend (1674–1738) who helped to promote the Norfolk four-course rotation. We must not forget that the period also saw the introduction of important new breeds of livestock through the researches of men like Robert Bakewell (1725–95), of Dishley Grange, who farmed the heavy clay lands of Leicestershire.32

When one reads the correspondence of the different ‘Improvers’ it is hard not to be carried along by their sheer infectious enthusiasm. It is abundantly clear that they were convinced that their work was important for the general good of society. They were not in it either to create agricultural ‘improvements’ for their own sake, or just to make money (although that helped). The concept of ‘improvement’ had a philosophical basis firmly rooted in the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. It was seen as a part of the new rational ideal, the triumph of civilisation over nature. It’s not for nothing that great agricultural ‘Improvers’, such as Coke of Norfolk, were also keen landscape gardeners. As with the new style of farming ‘Neatness, symmetry and formal patterns, so typical of the eighteenth-century landscape garden, represented the divide between “culture” and “nature”. Indeed, many landlords saw little difference between the laying out of parks around their houses and the new farmland beyond.’33

The ‘Improvers’ were undoubtedly remarkable men, but for various reasons to do with their social status at the time, or their enthusiasm for the promotion of a pet project (such as Tull and the seed drill), they have been treated more favourably by history than many of their humbler contemporaries. Modern research is, however, starting to redress this imbalance, largely thanks to detailed studies of individual estates and farms by historians such as Susanna Wade Martins, whose work is helping to transform our understanding of the period.

I hope readers will forgive me, but at this point I cannot help thinking how strange it is that certain remarkable people can drift in and out of one’s life, barely leaving a ripple in their wake. Only later do you kick yourself for not seeking out their views at the time. It’s rather like being the man who chose to argue the price of eggs with Sir Isaac Newton. In the case of Susanna Wade Martins, her husband Peter was the director of an Anglo-Saxon excavation I took part in, in 1970, at their home village in Norfolk. Susanna was around and about, but I knew her interests lay outside our dig and, afflicted by the myopia of youth, I failed to discover what she was researching at the time. A major lost opportunity, that.

Over the years, and perhaps more than anyone else, Susanna has thrown light on the lives of individual farmers; maybe this is in part because her academic work is deeply rooted in the experience that she and Peter have acquired running their own small farm. Indeed, as I have related elsewhere, we bought our first four sheep from them, back in the early 1980s.34 Peter warned me that sheep could become addictive – and he was dead right.

Susanna sees the initial development of modern British farming as being the responsibility of ‘yeoman farmers’. These men and their families emerged from the slow collapse of the feudal system and became very much more common in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Yeomen were independent, small farmers who usually owned most, if not all of their own land. Later, they might enter into tenancy agreements with larger landowners, while retaining a core of land for themselves. In some instances they used the profits of their land to acquire estates and to better themselves in the greater worlds of politics and industry. A good example of a successful yeoman family were the Brookes of Coalbrookdale who did so much to develop the iron industry there in the later sixteenth century – but more on them in Chapter 5.

It was yeoman farmers who developed the system of ‘up and down husbandry’ in the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This system involved a sort of long-term rotation where the land was cropped for arable – usually cereals – for, say, seven successive years, before it was returned to pasture to recover for a slightly longer period of up to a dozen years. This sort of farming was very productive and was adopted across most of the English Midlands. Interestingly, although the population of Britain was rising from 1670, grain prices actually fell year on year – which indicates, if anything can, the productivity of ‘up and down husbandry’.35

Landowners only start to become generally interested in agricultural ‘improvement’ from round about 1750, following directly upon the demonstrable successes of what some have called the ‘yeoman’s revolution’ of the seventeenth and earlier eighteenth centuries.36 Prior to 1750, most landowners had invested any profits from their estates, not so much in farm improvements as in extra land or in additions to their stately homes. After that date they (and their agents), having seen what the yeoman farmers were able to achieve, decided also to invest time, money and ingenuity in improvements to their own farms.

By the mid-eighteenth century the attitude of most British landowners to their tenants had begun to change significantly. A national market was also beginning to emerge for farm produce. Prices for wheat rose steadily and then shot up when Britain declared war on France, in 1793. It now became a patriotic duty to ‘improve’. These developments allowed landlords to increase their rents, and tenants to pay them. After 1750 both yeoman farmers and successful tenant farmers had prospered and were now in a position to negotiate new tenancy deals that stipulated realistic rents and encouraged landowners to invest capital in the new farm businesses.

From the mid-eighteenth century the old subservient relationship of tenant and landlord was gradually being replaced by partnerships where both parties profited from a shared enterprise. From as early as the Restoration (1660) independent yeoman farmers began to be replaced by a growing body of tenant farmers, and the more successful of these were able to take advantage of the wholesale reorganisation of estates that was happening through enclosure, which, as we have seen, was well under way when King Charles II resumed the throne.

To place these developments within context, the century from 1640 saw London’s population increase by 70 per cent, and the growing metropolis was successfully fed by farms linked into the system of markets via a well-used specialised network of drove roads, which allowed sheep and cattle to be driven long distances from places as far afield as Scotland, down to specialised farms in East Anglia and the Home Counties, where they could be fattened for slaughter.37 So the system worked and both landowners and their tenants prospered. But Susanna Wade Martins points out that the landowners were not looking for tenants motivated by Enlightenment ideals; instead they sought practical men who would be able to maximise income from their farms.38 Social attitudes were changing.

This very broad-brush account of the first two centuries of post-medieval farming forms the background to the relatively few buildings of the period that still survive in the landscape. As we saw in the case of Shapwick, our best chances of learning about early modern times come from studying the final years of the Middle Ages. Rather strangely, perhaps, I cannot find studies that are specifically addressed towards rural sites and landscapes of the decades that followed the medieval period. It’s almost as if nobody cares. More to the point, I suspect this void reflects one of the great historic divides in British archaeology, between the academic worlds of medievalists and post-medievalists or industrial archaeologists. In the past two decades, however, detailed regional research projects, although often geared towards specific periods and problems, no longer just ignore those topics that are not of immediate interest to them.39 Along with a greater emphasis on entire landscapes rather than specific sites has come the realisation that continuity has more to teach than a narrow concentration on a particular period.

One of the best of these new regional studies has examined some twelve parishes in the heart of the Central Province on the Buckinghamshire–Northamptonshire border.40 Recently the principal results of the Whittlewood Survey, as it is known, have been published and they show clearly that it can be very risky to make sweeping statements about rural settlement at the close of the Middle Ages. It would seem that while some villages, especially in those areas where the settlement pattern had been concentrated or ‘nucleated’, to use the correct term, were actually abandoned, others shrank, sometimes forming two sub-settlements within the same parish. This is not an uncommon pattern in lowland England. Indeed, the village where I grew up at Weston, in north Hertfordshire, had two clear centres, a smaller one around the Norman church and a larger, slightly later one around the village crossroads and the principal inn, the Red Lion, where I spent much of my youth.

Although on a larger scale than Shapwick, the Whittlewood Survey also combined detailed documentary research with field-walking and limited excavation and they were able to demonstrate the extent to which individual villages had changed their shape at the close of the Middle Ages. One example should illustrate the point.41 Although most of the shrinkage that villages experienced during the later Middle Ages resulted in the random loss of houses, rather like gaps in a set of teeth, such a haphazard pattern was not universal, however, and it would seem that people were aware that communities needed to remain coherent, if not intact. This sometimes gave rise to village layouts where whole districts rather than single houses were abandoned.

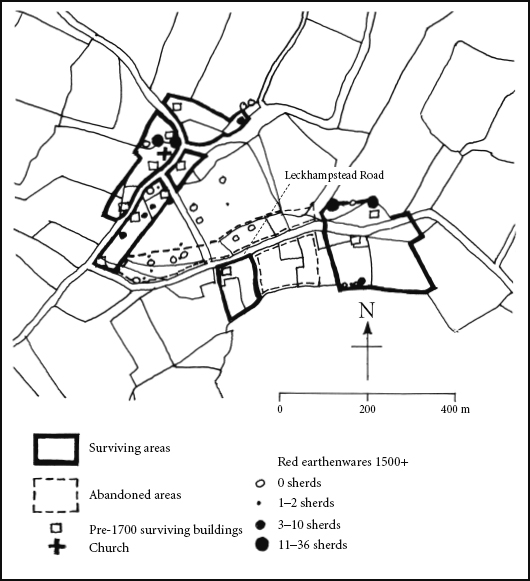

The Whittlewood Survey showed that the centre of the village of Akeley in Buckinghamshire, along the existing Leckhampstead Road, had been abandoned quite early (by 1400). The survey was based on an enclosure map of 1794 which marked the houses of the main village around the medieval church and an outlying hamlet to the east of the by then long-abandoned Leckhampstead Road community. Plainly a map as late as 1794 cannot be taken as an accurate illustration of the later and post-medieval settlement pattern, so the survey also recorded the presence of houses that probably pre-dated 1700. In addition, they dug a series of very small test pits where the finds were carefully retrieved and sieved. These pits revealed a fascinating picture. They completely failed to discover sherds of Red Earthenware pottery, so characteristic of the sixteenth century and later, either around the abandoned Leckhampstead Road settlement, or in the fields between the two surviving communities, where, by contrast, such pottery was abundant. Clearly both these settlements thrived in the sixteenth century.

FIG 3 A survey of the Buckinghamshire village of Akeley, based on an enclosure map of 1794. The distribution of pottery and of surviving buildings that pre-date 1700 clearly show that the centre of the original medieval village had been abandoned. Documentary sources suggest this happened very early, before 1400, but the new pattern continued largely unaltered into the sixteenth century.

Although the population declined in the later Middle Ages, the housing stock was deteriorating. This partly reflected the fact that many medieval buildings were made of timber, which soon begins to decay if maintenance ceases for any length of time. So the houses of ordinary rural people of the sixteenth and earliest seventeenth century are remarkably scarce. Very often the best way to find them is to examine seemingly late medieval buildings, which often, on closer inspection, prove to be more complex. A good example of this is given by Maurice Barley in his very readable and pioneering study The English Farmhouse and Cottage (1961).42 Maurice used to be the Chairman of the Nene Valley Research Committee when I excavated at Fengate, in Peterborough, during the 1970s, and I used to look forward to his site visits keenly. He was excellent company and like many of his contemporaries was equally at home in an excavation or working out the different phases of a medieval house. He certainly needed these skills when it came to a house in Glapton, Nottinghamshire, which was torn down in the senseless orgy of post-war destruction in 1958.

The Glapton farmhouse showed how a post-medieval farmer had made the most of the then dire housing supply by adapting an earlier, medieval, cruck-built barn sometime around 1600.43 Readers of Britain in the Middle Ages will recall that crucks were those long, curved beams that ran from the foot of the walls up to the apex of the roof.44 Many crucks were made from black poplar which was abundant at the time and which always curves its trunk away from the prevailing winds. But what makes this building so fascinating is the fact that the original medieval cruck beams had been numbered by the carpenters who erected them. Maurice quickly spotted this and was able to deduce that the eastern bay had been demolished when the building of the new conversion began.

So our anonymous Nottinghamshire farmer – who knows? Possibly an early yeoman – had spotted the Glapton barn as being ripe for conversion. The original building was of three bays and he still required half of it (i.e. 1½ bays) as a barn, for storage. He converted the remaining half-bay into a small farmhouse which he extended well beyond the old barn, mostly to the east – just as one sees so often today when Victorian barns are converted into houses, or second homes. The new timber-framed house was laid out in a way that was not strictly speaking medieval, but would nonetheless have been familiar to someone from the Middle Ages: there was a hall and parlour facing each other on either side of a cross-passage which led to service rooms (dairy, kitchen and buttery) behind the parlour. The house continued to be modified in various small ways for the rest of its long, but sadly finite, life.

If, as the Glapton barn/house showed, physical evidence for the rise of the first yeoman farmer families can be hard to track down, the success of their descendants has left a distinctive mark on the landscape, in the form of some fine seventeenth-century houses. These houses indeed proclaim the message ‘We have done well in life’, but without the over-the-top ostentation and tasteless vulgarity of the much later ‘financial crisis’ profiteers. The latter eyesores are aggressive and lack any charm whatsoever, whereas their seventeenth-century antecedents reflect the fact that their builders were still rooted in the real world of cattle and sheep, ploughs and ploughmen. I suppose in the final analysis the surviving yeoman farmhouses of Britain can justify their prominent place in the countryside, because they were based on genuine risk and on real, non-paper products that actually fed the rapidly growing population.

The century after 1720 witnessed the rise of a new type of carefully laid out and planned farm whose architecture reflected the classical ideals of the great landowners of the time. These buildings are often Italianate in style, reflecting Palladian grace just as much as the need to house cattle or store turnips. What a great shame it is that modern farmers have completely abandoned any attempt to give their crudely functional buildings any architectural merit at all. It’s as if they felt obliged to proclaim that their structures were erected to do the job cheaply and efficiently and to hell with the look of the landscape. They could learn much from later eighteenth-century architects such as Daniel Garrett or Samuel Wyatt whose elegant Italianate farm buildings still function as they were originally intended. Some of his best-known creations can be seen around the estate of ‘Coke of Norfolk’, at Holkham Hall.45

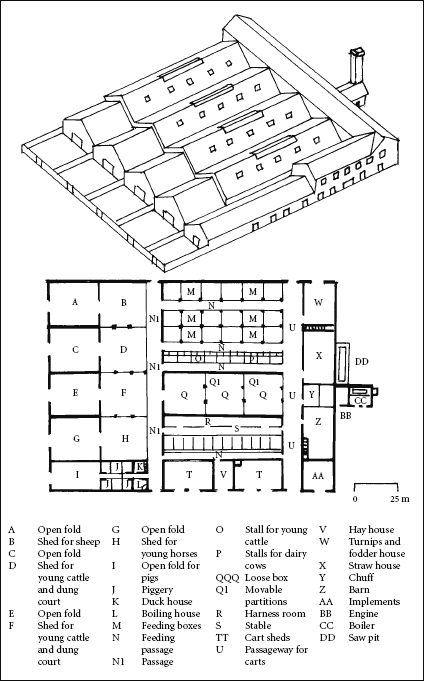

Many of the elegant Italianate buildings of eighteenth-century model farms were still successfully in use during the next major phase of British farming, sometimes known as Victorian high farming, which began around 1830 and lasted until the great agricultural depression of the 1870s. This was a period of unparalleled prosperity which saw the construction not just of well-planned and laid-out new farms, but of farms which, even by today’s standards, would be regarded as industrial. Designs for farms of this sort can be seen in contemporary pages of the sort of journals that progressive landowners read, such as that of the Royal Agricultural Society of England, where the range of buildings by J. B. Denton, illustrated here, first appeared.46 Today nearly every medium-sized farm in Britain can probably boast a few buildings of this era, but those belonging to large estates where capital-rich landowners were able to choose competent tenants and together form mutually beneficial partnerships, are particularly well endowed and have left us a rich legacy of fine farm buildings. I shall have more to say about the development of farms and farming on large rural estates in the next chapter.

FIG 4 The prosperous era known as Victorian high farming lasted for much of the nineteenth century, from 1830 to 1870. It saw an increasing number of close partnerships between landlords and tenants, where the latter acted as efficient managers and the former provided capital. The resulting farms could sometimes resemble large factories. The farm buildings shown here are from a design by J. B. Denton of 1879, and were erected at Thornington, near Kilham, Northumberland, around 1880.

In lowland England, if not in Wales and Scotland, it is probably true to say that the big and medium-sized farms of the nineteenth century have had a disproportionately large influence on the shape of the modern landscape. Recently archaeologists have quite rightly focused attention on these places, which for some reason were largely ignored in the 1970s and 1980s. However, there is also a much older tradition of recording so-called ‘vernacular architecture’ which I will define for present purposes as buildings built by people rather than trained architects often using traditional designs and materials. I say ‘often’, because sometimes buildings that are vernacular in spirit can be fashioned from mass-produced components, such as some converted barracks in Shropshire or the ‘Tin Tabernacle’ in Northamptonshire, which I discuss in Chapter 7.47 There used to be hot debate about what buildings were truly vernacular and which were not. But it was a fruitless debate and today we are less concerned about what is or isn’t ‘truly’ vernacular and now include many threatened nineteenth- and twentieth-century buildings, such as prefabricated temporary school buildings and cinemas.48

Much of the earlier surviving post-medieval rural architecture of Scotland and Wales is vernacular and a surprising amount survives in England, despite, or in some instances because of, the era of high farming.49 Many farming families are quite conservative and were reluctant to demolish earlier buildings, which they often ‘improved’ by adding huge and usually unsympathetic new wings and ranges. My own great-grandfather more than doubled the size of his modest Queen Anne house in Hertfordshire, a few windows of which now appear to squint out from behind a massive red-brick late Victorian pile. Indoors, and with sufficient time to spare, you can just work out the shape of the earlier building.

The post-medieval centuries witnessed the creation of the diverse rural landscapes that we all inhabit. True, there is evidence within those landscapes of much earlier times, but this is often hidden away, as humps and bumps, or sinuous field boundaries. Most of the ‘furniture’ of the countryside, the fences, gates and the drystone walls that surround our fields, were erected in the past two centuries – and if not, you can be certain that they have been extensively repaired in that time. Similarly, although there are indeed a few surviving ancient hedges (although sadly we no longer believe that these can be aged simply by counting their component species50) these will have been laid, interplanted and today trimmed back by mechanised flail-cutters countless times in the last hundred years.

Anyone with even a passing knowledge of the British countryside will be aware that the eastern side of the country has a drier climate, which is why the landscape here is given over to arable and mixed livestock and arable farming. To the west the more moist, Atlantic climate tends to favour pasture. This broad distinction was first mapped by the farm economist James Caird in 1852 and it applies with even greater force today, when grazing livestock are almost completely absent across huge areas of east Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire and East Anglia.51 If livestock are absent I also fear for the knowledge and traditions that were once a part of animal husbandry. The much-parodied grasping ‘barley baron’ whose eyes are only focused on the ‘bottom line’ and whose vision requires him to grub up all trees and hedgerows to create vast prairie-like fields, was, until very recently, not a complete figure of fun. Although most farmers used the availability of EEC grants responsibly, such men indeed existed and their depredations can still be seen, especially in parts of eastern England.