Полная версия

The Birth of Modern Britain: A Journey into Britain’s Archaeological Past: 1550 to the Present

I have always had an interest in what one might term modern archaeology and found I had more time for it after I had completed work on the report of my excavations at Flag Fen, a process that occupied me, night and day, for some five years in the mid-1990s. When that was finished I decided I really had to get out more, see the world and ‘get a life’. But I still had a deep and abiding interest in the past and the story behind the creation of modern Britain. So I found my attention was gradually shifting forwards in time. I was, however, completely astonished by the sheer diversity I encountered when I delved more deeply into the archaeology of modern times. It wasn’t just about the obvious themes: the growth of industry or agriculture and the development of towns. I also found that students and researchers were approaching even these topics from unexpected directions, often with surprising results. This was one of the other reasons I decided it was impossible to present a ‘balanced’ view of the archaeology of post-medieval times and have opted instead to examine projects and ideas that give one a new slant or perspective, if not a ‘sideways’ look at the period. Although there are a few excellent history books that cast their nets wider,14 too often such accounts approach early modern Britain from the viewpoint of the great and the good. Theirs is a story of major politicians, generals, bishops, kings, queens and princes. Mine, I hope, will be about everyone else.

Finally, I must say a few words about the way this book has been organised. Readers of the three other volumes of this four-part archaeological history of Britain will have grown used to a straightforward chronological layout. In fact, I’ll be quite honest and admit that, for the sake of consistency, I tried to organise this book in the same way. But sadly it just didn’t work. I found I was attempting an impossibly difficult juggling act with too many balls in the air at one time. Put another way, too much was happening too quickly across too many different areas of life to sustain a coherent narrative, especially when I switched themes, at which point, like a bad television documentary, I was forced to summarise or recapitulate ‘the story so far’. Anyhow, after a few weeks I abandoned the unequal struggle and decided instead to follow a series of general themes, chapter by chapter. These topics will, however, be approached chronologically. Of course an author is never a good judge of such things, but, fingers crossed, I think it works rather better than I once dared to hope.

* I use the terms Scheduled (for ancient sites) and Listed (for standing buildings) to denote that these places are protected by Act of Parliament.

Chapter One

Market Forces: Fields, Farming and the Rural Economy

SO FAR MY investigation of Britain’s archaeological past has taken me almost two millennia this side of prehistory, my own area of expertise. I am now deep within unknown territory, what medieval adventurers might have described as terra incognita. With this in mind I trust readers will forgive me if I follow an old excavator’s principle and work from the known to the unknown.

So I want to start our exploration of Britain in the post-medieval period in the farms and fields of the countryside. There, at least, I feel reasonably at home and not just because I was brought up in a small village, but because over the past thirty-odd years my wife Maisie and I have kept a small sheep farm which would regularly make a tiny profit, until, that is, 2001, when the market value of British livestock collapsed, rather like wheat prices after the Black Death. In our case the miscreants have been BSE/scrapie, foot-and-mouth (twice) and now the dreaded Bluetongue in all its grisly variants. More recently, and much to our surprise, things have picked up. This improvement followed directly on the bursting of the bankers’ bubble in 2008, when the collapse of cheap credit forced an international reassessment of what matters in life. At last people have recognised that the era of cheap food was always unsustainable. Anyhow, my interest in sheep-farming has given me insights into, and much sympathy for, historic and ancient farmers. So let’s start our journey where the food that nourishes human life originates: with farms, with farmers, and their families.

I would guess that over the years archaeologists have excavated hundreds, if not thousands, of prehistoric, Roman and medieval farms, farmyards and field systems. I myself have dug upwards of a dozen. But with one exception, which I will discuss shortly, I cannot think of a single post-medieval or modern farm that has been treated in this way.* This simple fact illustrates, if anything can, how different is the way that post-medieval archaeology is carried out. There are fewer excavations and instead far, far more effort goes into the accurate surveying of upstanding remains which are then painstakingly tied in with the documentary evidence. So that’s how things are done and to some extent it makes complete sense, because why dig when you can measure and survey at a fraction of the cost?

It is all perfectly rational, but nevertheless the digger/excavator deep down inside me feels a bit uneasy: surely without entirely new and unexpected information from the ground there is always a danger that observations derived from surveys can somehow be made to ‘fit’ the documentary evidence? True, these two strands of research can together combine to reveal fascinating stories, but, speaking entirely for myself, I sometimes enjoy seeing theories – even my own – being turned rudely upside down. The inevitable rethink that follows can be wonderfully invigorating and is far cheaper than a bottle of Champagne. That’s what makes the writing up of an excavation such fun: it becomes a prolonged process in which pennies drop with unexpected force, delight and frequency.

British archaeology has a distinguished history of long-term projects in which one or two slightly obsessive characters – and I’m happy to number myself among them – assemble a team of similarly slightly obsessive people who then work closely together, often lubricated with quantities of drink and coffee, to reveal the archaeological story of a particular place or region. In my various books on Britain’s archaeology I have had good reason to thank these people whose work I have ransacked for ideas. Often these long-term projects can produce fascinating tales that develop gradually over the years and become suffused with a life and vigour all of their own. One of the very best of them is about the archaeology of the small Somerset parish of Shapwick. We first visited this village on the edge of the marshy Somerset Levels in Britain in the Middle Ages.1 As I explained there, one of the slightly obsessive characters behind the Shapwick project is my old friend Professor Mick Aston, better known to millions of viewers today as the grey-haired archaeologist in the stripy jumper on Time Team.

Although not religious himself, Mick will go to great lengths to help a church in difficulties and when, in the summer of 2007, I read in our local paper that the magnificent building in Long Sutton needed urgent repairs to its roof, I thought of Mick, and together we organised a public lecture, which was to launch the vicar’s appeal for funds. The church is rather extraordinary. Like many around the Wash, it is very large and appears on the outside to be quite late – maybe fourteenth century – but when you enter be prepared for a surprise, because the interior is almost completely Norman, and Norman of a very high order. Mick got wildly excited and was convinced that the superb workmanship around us was Cluniac (a monastic order famous for its first-rate buildings). This book isn’t about the Middle Ages (and I’ll get to the point in a moment), but Mick’s presence drew a huge crowd and the church was thronged with people. There were stalls selling local books and magazines, and the nearby village hall supplied a stream of people contentedly munching their way through vast Fenland cow pies. I was forcibly struck by the scene and realised that the church had suddenly become what it was in medieval times: the centre of a bustling community and not the exalted, pious and remote place that so many country churches have become since the liturgical reforms of Victorian times.

The following morning Mick appeared clasping what had to be the thickest paperback book I have ever seen. He thudded it down on my desk. It was, or rather is, a staggering 1,047 pages long and includes a CD-ROM of many hundreds more. Having written one or two thickish tomes myself, I know just how much effort it must have taken Mick, and his long-term collaborator, Chris Gerrard, to write and assemble such a Goliath. And now, a few weeks later, I have more or less digested its main findings and it is indeed an astonishing work of great scholarship. It is the account of a survey that took place over a decade, from 1989 to 1999, and involved the methodical field-walking and selected excavation of most of the parish of Shapwick.2

Field-walking, incidentally, is the process whereby a group of archaeologists walk slowly over a field, carefully following a grid. As they walk they put any finds they can see on the surface into bags which are marked with a grid reference. Strange as it may seem, this can be very hard work: on wet days heavy clay sticks to your boots and soon your shoulders start to ache because your head is permanently inclined towards the ground; by this stage, too, the constant dipping down to pick up finds gets to the muscles in your back and calves.

You might think that field-walking would best be done in the warmth of summer, but in fact it doesn’t work like that. Obviously land put down to woodland, grass or permanent pasture can’t be fieldwalked, but neither can ground that has been freshly ploughed or harrowed. Ideally, cultivated land should be left to the mercies of wind, rain and frost for at least three weeks before it is walked. That way, finds are washed clean and can readily be spotted on the surface. After a day’s walking, the bags are taken somewhere dry where they are emptied, the finds washed and divided into various categories, such as bone, flint, tile, pottery, brick and clay tobacco pipe fragments (which are common on post-medieval sites of the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries).

One reason why post-medieval archaeology is so important is that it allows us better to understand what archaeologists sometimes refer to as ‘formation processes’. In the past these tended to be assumed or were simply taken for granted, which was a shame, because in fact they are crucially important. So what are they? Perhaps the simplest way to think about them is to ponder the many possible ways that archaeological deposits were formed in the very first instance. Take an obvious example: when rubbish was swept under a reed mat or when coins slipped through holes in a tinker’s pockets to land in the mud of a garden path. Some could have been formed through deliberate dumping (what today we would call ‘fly-tipping’), or during religious offerings, sacrifices or perhaps in the course of a cataclysmic event, such as a fire, earthquake, hurricane, tsunami or the eruption of a great volcano.

Usually one can rule out certain options. Earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are generally infrequent in Britain, for example. But then it gets more complex. Dredging of the Thames to allow larger ships upstream in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries revealed huge quantities of Bronze Age weapons and human skulls. At the time it was assumed that these had been washed into the river from settlements along the shoreline. Somewhat later people preferred to think that much of this material had been lost when ancient travellers had attempted to ford the river. Today we tend to regard most of these river finds as being the result of deliberate religious offerings to the waters. In fact, there is precious little by way of hard and fast evidence to support any of these suggestions. As a general rule such explanations tend to depend on which theories are currently fashionable in academic circles – and nowadays ideas centring around religion and ritual are much in favour.

So let’s suppose that we’ve emptied the contents of our field-walking bags onto a table. The first problem one has to address is simple: how did these hundreds (more usually thousands) of things find their way into, and onto, the ground? Now with very ancient prehistoric material it can be difficult to decide what surface finds actually represent. Soft, poorly fired pottery rarely survives attack by the humic acids in the ploughsoil, and bone succumbs quite quickly as well. So their absence does not mean that they were never there in the first place. As a result, all one is usually left with is flint. And it’s usually impossible or very difficult to decide whether a scattering of flints originated from a permanent village, a camp or a temporary squat, where a handful of hunters stopped to prepare a few new arrowheads after breakfast.

Such conundrums can be easier to unravel in Roman and medieval times when the appearance of bricks, roof tiles and mortar can signal the existence of demolished buildings. But again, although Roman pottery is harder and tends to survive rather better in the soil, bone can soon vanish and iron rapidly rusts away to nothing. Only in post-medieval times does material survive so well in the topsoil that it becomes possible to decide with some certainty how, and indeed why, it originally became incorporated into the earth. And strangely, as Shapwick has shown so clearly, the manner in which some of this material seems to have found its way into the topsoil could be unexpected.

Viewed from an historical perspective, the end of the Middle Ages was traumatic, what with the Reformation, the rise of the Tudors and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. But although these were indeed major events, we will see that their actual impact on the growth and development of Britain’s rural and urban landscapes was surprisingly small. Of course specific sites – and here I am thinking most particu-larly of rural and urban monastic estates – were dramatically affected, but the general run of the landscape was not. It is becoming increas-ingly clear that many of the processes that became self-evident in the mid-sixteenth century had roots very much earlier, usually in the mid-fourteenth; this was the period which witnessed the first impacts of the successive waves of plague we generally refer to as the Black Death. We can see this continuity particularly clearly in the distribution of surface finds at Shapwick.

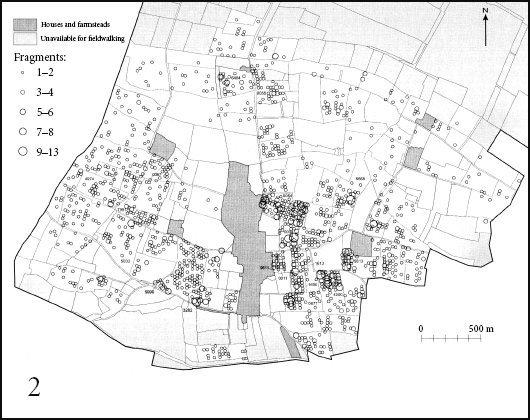

FIG 1 Three maps of Shapwick, Somerset showing (1) the distribution of later medieval (twelfth–fifteenth centuries) and (2) post-medieval (sixteenth– eighteenth centuries) pottery; map 3 shows the distribution of unidentified brick and tile fragments. These maps clearly demonstrate that there was no break in settlement at the close of the Middle Ages.

I have described how the range and robustness of post-medieval topsoil finds often provide clues as to how they found their way into the ground. Take an obvious example: if surface scatters of brick, tile, cement and plaster are discovered in a field, one might reasonably suppose this was the site of a demolished or collapsed building. Similarly, quantities of pottery and animal bone might indicate the erstwhile presence of rubbish tips. But here we immediately encounter problems, because the idea of useless rubbish is essentially a modern concept, and one which is already, thankfully, on the way out. Even as late as the nineteenth century much rubbish, including human excrement, was actually recycled and spread on the land where it provided a valuable source of nitrogen and other minerals. ‘Night soil’, as the contents of London’s many millions of privies was called, was spread on the fields growing vegetables in Bedfordshire and Middlesex, especially on the lighter gravel soils around Heathrow.

The men given the unenviable task of filling the carts and then transporting and spreading the night soil would smoke a lethal dark shag tobacco in clay pipes, believing this would keep illness, as well as the stink, at bay. Today if you field-walk these fields you will be rewarded by the discovery of thousands of broken pipe fragments. So the discovery of pieces of pipe provides a good indication of how that particular soil might have originated. There are also other clues that allow us to make an informed guess about a deposit’s formation process.

At Shapwick the concentration of small, unidentified brick and tile fragments did show some correspondence with the pottery distribution, but there were also other concentrations further away from the village, some of which could be associated with known demolished post-medieval buildings. Others seemed to have been dumped, most probably after a tile roof had been renewed or repaired. This distribution suggests that brick and tile was finding its way into the ground through a variety of quite different processes. But what about the quite clear replication of the brick/tile distribution with that of the pottery, especially to the immediate east of the village, where both seem to form a concentration in a broad strip, running north–south? We know that this strip was in existence in later medieval times and it is probably best explained as the detritus left, following the spreading of manure.

Today farmers tend to keep their farmyard manure and domestic rubbish separate, but I can remember farms in my childhood where the edible contents of the kitchen pail was fed to pigs and chickens while the stalks and bones were chucked away on the muck heap. Now the muck heap was not the foetid mess that townspeople might suppose. Its purpose was to allow muck to break down – today we would rather primly refer to this process as ‘composting’ – and become manure. This maturation usually took a year or less to complete. It’s worth noting here that if muck is spread onto the fields too soon it has precisely the opposite effect to that intended: it breaks down in the arable ground and in the process removes nitrogen from the soil. And of course it is nitrogen that plants require if they are to grow vigorously.

In the past, household and other debris was placed on muck heaps, which archaeologists, for reasons best known to themselves, like to refer to as ‘middens’. Middens also accumulated burnt wood (for the potash it contains), from which thousands of nails found their way into the soil. In regions where the subsoil was heavy or acidic, farmers would add broken bricks and mortar to help drainage and increase alkalinity. Pottery and glass sherds also helped clay soils to drain, so they were thrown onto the midden along with everything else. Then the process of hand-forking the manure into and out of carts helped break down the pieces of pottery, glass, brick and tile, which would explain the small size of so many of the sherds from that strip immediately east of Shapwick village.

So the distribution of finds from later medieval and post-medieval Shapwick proves beyond much doubt that the villagers continued to live in very much the same place and spread their manure in much the same way from at least the twelfth to the eighteenth centuries. After that time in Britain generally we see the gradual introduction of non-farmyard fertilisers, of which the best known is bird dung from the Peruvian coast, known as guano, but other soil improvers were also used, such as gypsum, chalk and lime.

It is now becoming clear that the farming and manuring pattern of later medieval times continued into the post-medieval period relatively unaltered, yet this was a period almost of turmoil in the world of local landowners. Glastonbury Abbey, always a prosperous foundation but possibly the richest monastic estate in England by this time, owned land and two manors at Shapwick which were taken over by private landlords after the abbey’s dissolution in November 1539. This led to the enlargement of the mansion at Shapwick House sometime around 1620–40 when a long gallery was added to the medieval building. All this was happening, and yet the basic management of the landscape continued much as before. It is not, however, until the later eighteenth century that we see the village decline in size as the park around Shapwick House was greatly enlarged, a process sometimes referred to as emparkation. We know, for example, that seven houses near the great house were demolished between 1782 and 1787.3 This process continued until the great park was completed in the 1850s, a process which even involved the relocation of the parish church!

At this point I should perhaps admit I’ve been a little unfair because I’ve started this chapter by jumping straight into the deep end of a pool of detail. I did that because I wanted to illustrate the complexities inherent in any attempt to understand how the rural landscape developed at this crucially important period at the very beginning of our story. But our tale is about to get more complicated. In many ways this reflects the reality of modern research into rural archaeology: many of the old certainties have had to be abandoned in the face of a growing mountain of evidence that what might once have been seen as clear national trends actually fail to apply at the local level. But this is nothing new, as we saw in the Middle Ages.

One of the great archaeological breakthroughs in the study of English medieval rural geography happened in the 1950s and 1960s with the recognition that many villages in the English Midlands had either been abandoned or had shrunk massively, usually from some time in the fourteenth century. When mapped out, these villages could be seen to form a Central Province which extended in a broadly continuous swathe from Somerset, through the Midlands, Lincolnshire, eastern Yorkshire and into County Durham and Northumberland.4 The landscapes in this area featured villages that had been reorganised, or ‘nucleated’, by drawing outlying farms into a more focused central village, a process that happened in the centuries on either side of the Norman Conquest. The work of nucleation was carried out by local people, often encouraged by landlords and by other authorities, such as the Church and great monastic houses (as happened at Shapwick).

On both sides of this Central Province of ‘planned’, nucleated or ‘organised’ landscapes, the countryside was less formally structured, with dispersed settlements and smaller hamlets rather than nucleated villages. This landscape has been variously described as ‘ancient’ or ‘woodland’, but as both types are now known to have been very old indeed, I shall stick to the term ‘woodland’ as being slightly less misleading.5 The distinction between the Central Province of nucleated and the provinces of woodland landscapes on either side can be seen in the distribution of known pre-Norman woods and even, to some extent at least, in that of Pagan Saxon (mainly fifth-century) burials.6 So whatever allowed people of the Central Province to accept these changes, it must have been a social process with deeply embedded roots. Even more importantly for present purposes, the three provinces can clearly be distinguished when we plot the distribution of nineteenth-century parliamentary enclosures (about which more shortly). Today the landscape still reflects this tripartite split, with larger villages and more formal rectangular fields still largely confined to what had been the Central Province.

Farming in the woodland landscapes continued much as it had done in the Iron Age. It was based on individual holdings, which operated a mixed system of farming based around livestock and crops in those areas where lower levels of rainfall allowed them to be grown. The larger nucleated villages of the Central Province gave rise to the now famous collective Open Field farms of the Middle Ages where tenant farmers in the village shared their labour between their own holdings and those of the lord of the manor.7 This was the basis of the feudal system, which never developed in Britain to quite the same extent as it did on the Continent. Farmwork itself took place in from two to four huge Open Fields where the individual holdings were organised in strips. Each year the individual Open Fields would grow specified crops or would lie fallow, to be fertilised by grazing livestock. The control of what was in effect a large collective farm lay in the hands of the manorial court, which in turn was overseen by the lord of the manor. This system of farming was particularly well adapted to the heavy clay lands of the Midlands, which require rapid ploughing by many teams of oxen in the spring when conditions are right. Get the timing wrong and you’re left with a porridge-like field of mud.