Полная версия

The Birth of Modern Britain: A Journey into Britain’s Archaeological Past: 1550 to the Present

Indeed, anyone blessed with good eyesight could appreciate the devastation that was caused to the landscape of lowland Britain from about 1950 to 1990 when some 400,000 kilometres of hedgerow were destroyed.52 As I noted, much of this was perpetrated in the name of agricultural progress (I almost mistakenly said ‘improvement’) and often with huge injections of taxpayers’ money. The trouble is that any taxpayers with interests other than increased agricultural efficiency were simply ignored. With the single exception of Scheduled Ancient Monuments (i.e. sites protected by law), no regard was taken of any archaeological remains that might be damaged by the new methods of power-farming. After some thirty years of unrestrained destruction, during which the vast majority of lowland sites and monuments were either destroyed or severely damaged, the powers that be reluctantly acknowledged that the plough was a threat to what little remains of our past.53

Let’s finish this chapter by taking the long view. There can be little doubt that there were far larger changes to Britain’s rural landscapes than those that began in and then followed the Second World War. The arrival of farming itself in the Neolithic, around 4500 bc, is an obvious example. The development of the first fields in the earlier Bronze Age, from about 2000 bc, is another. In historic times further eras of change included the later Saxon period (in, say, the three centuries after ad 800), when we saw the rise of the Open Field system and the nucleation of dispersed settlements into more compact villages.54 Finally, and as we have just seen in this chapter, the disruption to rural life caused by successive waves of plague in the two centuries following the Black Death of 1348 was to prove of great importance, as it led directly to the regionalisation of the countryside that was such a prominent feature of the early modern period.

The rural transformations of prehistory and history, however, happened slowly, usually as part of more widespread changes in northern Europe (although the development of fields in Bronze Age Britain does still seem to have been a largely insular development).55 And when I say ‘slowly’, I mean over at least two, and more usually three or four centuries. In the case of the Neolithic adoption of farming, the process took a full millennium. But the changes that the British government decided to push through, in order to meet the threat to food supplies posed by the Nazis across the Channel, happened very rapidly indeed. Something broadly similar took place in the Roman period when southern Britain became, in effect, the western Empire’s ‘bread basket’, providing huge quantities of wheat for the Roman army. But unlike the rural reforms of the Second World War, the Roman changes were reversed in the late fourth and fifth centuries, when the troops were withdrawn – and large areas of the countryside reverted to grassland.56

The rapid movement out of pasture and into cereals and other crops that happened between 1939 and 1945 seems to have had a permanent effect. Recent research has drawn attention to the wartime changes to British farming which were intended to feed the populace, despite Hitler’s U-boat Atlantic blockade.57 Those reforms were urgently needed but they helped turn farmers and landowners from countrymen to businessmen, and everything that followed – especially the grant-driven over-production inspired by Brussels – was made possible by what happened then.

The wartime changes to the farming economy and landscape of Britain do help explain why subsequent developments, largely funded by EEC grant-aid in the form of the Common Agricultural Policy, or CAP, had such different effects on either side of the Channel. The small – tiny by British standards – landholdings of the French countryside were largely sustained by the injection of CAP cash – as, indeed, the legislation had intended from the very outset. But in Britain the far larger landowners and farmers, who had developed their businesses during the war, duly accepted the CAP handouts and used the money to further increase the size, and therefore the profitability, of their operations. They now had the capital to buy up smaller, generally less efficient operations, with the result that commercial farms in Britain grew rapidly in size throughout the seventies and eighties. Meanwhile in France, CAP money continued to support what was in effect a peasant-farming economy.

So ultimately, when I’m out field-walking and I angrily ponder the dark line left in the soil by a recently destroyed hedgerow, I first blame Nazis and then Eurocrats. I suppose it’s much easier than blaming myself, and millions like me, who allowed such terrible things to happen to the countryside of lowland Britain in the last three decades of the twentieth century.

If torn-out hedgerows are a prominent feature of the rural landscape bequeathed to us by the later twentieth century, then so-called ‘agri-mansions’ must be another. These large houses, built by successful farmers, contractors and farm managers, feature all the trappings of the more affluent outer suburbs, from swimming pools to gazebos and barbecues able to grill a medium-sized elephant. Large four-wheel-drives may be seen on their appropriately vast paved forecourts. These places were not built to conceal wealth. Far from it. They are latter-day symbols of power and prosperity: expressions in brick and stone of individual success and personal wealth. And as such, of course, they are nothing new.

*More to the point, nor can Dr Audrey Horning (University of Leicester).

Chapter Two

‘Polite Landscapes’: Prestige, Control and Authority in Rural Britain

IF THERE IS ONE aspect of Britain that is widely celebrated abroad it must surely be the literally astonishing beauty of its parks and country houses. I use the word ‘literally’ because I’ve long been addicted to house and church visiting and I still come across scenes in parks and gardens that make me gasp in astonishment. I will never forget, for example, a visit to Stourhead in Wiltshire, once the home of perhaps Britain’s greatest early archaeologist/antiquary, Sir Richard Colt Hoare. The park around Stourhead was designed by his ancestor Henry Hoare II and has remained open to visitors since the 1740s.1 The carefully laid-out walk around the great artificial lake takes one past a succession of beautifully positioned temples, vistas and grottoes.

As a keen gardener myself, I am convinced that the main reason why the layout of the grounds at Stourhead work so well is that Hoare created them gradually, by degrees. Unlike most garden designers today, he did not start with a blank piece of paper and then impose his design on the landscape. Instead, the design is the landscape, only subtly, and sometimes not so subtly, modified to fit its creator’s long-term vision. For me, Stourhead, together with Stowe (Buckinghamshire), Painshill (Surrey) and the water gardens at Studley Royal (North Yorkshire) are some of the greatest achievements of British art and design. One reason for their success is the discipline acquired by accepting the confines of their respective landscapes; I think this is why such gardens are infinitely superior to the stage-design set pieces one encounters today at events like the Chelsea Flower Show.

I well remember the hot autumn day when my wife Maisie and I first visited Stourhead. We had almost finished the descent from the last of the great garden buildings, the Temple of Apollo, and as we walked down the path we were both thinking similar thoughts, along the lines of a cool drink and a large sandwich. We approached the houses of Stourton, the estate village that successive owners of Stourhead had subtly altered to make more attractive, when my gaze was suddenly taken by a glint off the water to my left. I had forgotten all about the lake in my eagerness to find lunch and almost missed one of the greatest man-made views in the British landscape, over to the Palladian bridge and across the lake towards the Pantheon. I was so captivated by the scene before me that I then spent the next half-hour wrestling with cameras and tripod, attempting to take the perfect photograph. Meanwhile, lucky Maisie was grabbing something to eat before the pub closed for the afternoon.

Of course that view at Stourhead was no accident and was always meant to be the visitor’s final coup de théâtre. After more than two and a half centuries it had lost none of its power or magic. A succession of inspired individuals have contributed to the growth and development of the British landscaped park, which is still regarded by many as the nation’s greatest contribution to world art, so I would like to make it clear from the very outset that in this chapter I shall not attempt even a superficial history of its development, as others are far better qualified to do that than I.2 Instead, I want to look at what archaeology can reveal about what was happening around the periphery of the great houses, parks and gardens; at how the estates and houses that went with them were built and run; and how private individuals and public authorities together organised life for the ordinary inhabitants of rural Britain.

But first, a few words on garden history and archaeology which over the past thirty or so years have become sub-disciplines in their own right.3 One of their spin-offs has been the movement to restore old or overgrown parks and gardens to something approaching their former glories. This in turn has led people to research into more abstract subjects, like Georgian aesthetics and attitudes to landscape, because you cannot attempt sympathetic restoration without appreciating the subtleties of what the original gardeners and landscape designers were trying to achieve.4 There have been a number of major excavation projects like those by Brian Dix, at Hampton Court Palace, or the great ruined Jacobean house at Kirby Hall, Northamptonshire, which have subsequently been followed by the restoration of entire formal gardens.5 Garden archaeology has established itself as a subdiscipline in its own right. These highly specialised digs make extensive use of historical documents, and a variety of clever procedures, such as the meticulous plotting of the many rusted nails used to join the edging boards of long-lost flowerbeds.

As a general rule, many of the features revealed by garden archaeologists can be very slight. Although they are from a much earlier period, I’m put in mind of the shallow trenches dug for the elaborate box hedges at the palatial Fishbourne Roman villa in Sussex.6 Very similar traces have been found at the two sites just mentioned, Hampton Court and Kirby Hall. In many instances even these slight remains can be detected without putting a spade in the ground, through the use of various geophysical surveys.

Put simply, geophysics involves the use of highly sophisticated machines which are wheeled, dragged or lifted across the ground, and in the process record certain aspects of what lies beneath the surface.7 Resistivity meters measure minute fluctuations in the soil’s ability to conduct an electrical charge; magnetometers can detect tiny changes in the local magnetic field. Both techniques can reveal buried wells, post holes, ditches and walls.

Recently an entirely new generation of machines has come into being. Known as GPR, or ground penetrating radar, these instruments detect the way that radio waves are distorted and reflected back to a receiver on the surface. GPR plots a succession of buried layers and can penetrate deep into the ground. A particularly useful geophysical technique to industrial archaeologists is known by the rather unlovely name of magnetic susceptibility sampling, or ‘Mag Sus’ for short. Mag Sus can detect areas of magnetic enhancement caused by burning and can provide a fairly accurate indication of the temperatures involved – so it can readily distinguish, for example, between a bonfire and a furnace. More to the point, its results are instantaneous.

The rapid development of fast, lightweight, portable computers has revolutionised geophysics. When I began in archaeology in the early 1970s, I would routinely have to wait a week or a fortnight for my survey reports. Today it’s usual to have finished results in an hour or two. Indeed, when filming for Time Team, our resident geophysicist, Dr John Gater, has been known to produce an accurate printout in minutes.

Although, of course, they are deeply wonderful (and France, for example, is full of them), I have to say I don’t find strictly formal gardens very attractive, largely, I suppose, because I can imagine myself spending weeks and weeks meticulously trimming pyramids of box hedging and quietly going mad in the process. My own favourite restored garden is the one at Painshill in Surrey, which was originally laid out by Charles Hamilton between 1738 and 1773.8 As at Stourhead, visitors perambulate around a great lake and are treated to a series of contrived views which include the usual colonnaded temples and a magnificent Turkish tent, successfully and imaginatively re-created in fibreglass. Perhaps the greatest feat of restoration at Painshill involved the rebuilding of a fanciful watery grotto, complete with side chambers, waterfalls and glittering crystal spar stalactites.

Today it is true to say that gardens are places of beauty and pleasure, but they have largely ceased to be instruments of political advancement and even intrigue. While most gardens were indeed permanent fixtures, some were created for a specific purpose, often the visit of a monarch and his or her court, and were always intended to be temporary – rather like the show gardens at Chelsea. Much controversy has recently been caused by the reconstruction at Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire of such a temporary garden, created by Robert Dudley, Earl of Essex, to impress Elizabeth I when she made a two-week visit there for nineteen days, between 9 and 27 July 1575. Dudley, of course, is famous for being the Queen’s favourite and we can only imagine what might have been his true motives for creating such a magnificent showpiece, which cost English Heritage the eye-watering sum of £2,100,000 to reconstruct, largely on the basis of a sketch and a single, albeit detailed, eyewitness letter.9

The garden is now permanently open to the public and it does give visitors a good impression of the lengths that people were prepared to go to impress the Tudor court, although doubts remain as to the so-called ‘eyewitness’ letter, which may have been a contemporary spoof or satire on Dudley’s pretensions. But even if it was, one could argue that the garden it depicts might have been the sort of creation that would have been inspired by such a royal visit. On the other hand, there is some archaeological evidence to support it, such as the discovery by Brian Dix of fragments of a fountain similar to the one described in the letter. Taking all things together, I tend to accept that the garden was indeed constructed and I find the controversy, which has already generated at least one television documentary, fascinating. The modern re-creation was constructed just before the financial crisis and only six months later, in less profligate times, it now appears an excess. Doubtless the original garden impressed Her Majesty, but if I had been one of the impoverished tenants of the Dudley estate I might well have been rather less enthusiastic.

I have stated that I have no intention of attempting a history of designed landscapes, but it is worth pointing out that many books that approach the subject from an art historical background tend to ignore the complexity of what actually happened out there in the real world. Today garden fashions come and go with bewildering rapidity: a few years ago everyone was covering their lawns with pergolas and wooden decking, then they painted their garden furniture blue, and now one cannot step into even the smallest back garden without running the risk of toppling into a water feature. Much the same could be said about the past except that then taste was not dictated by television makeover programmes. Of course there were highly influential people, such as ‘Capability’ Brown or Humphrey Repton, whose general influence was widespread but there were also other, often complementary traditions, too.

Recently the landscape archaeologist and historian Tom Williamson has called for a more regional approach to garden archaeology. There is a natural tendency to sing the praises of a particular, often grand garden and to make it sound as if it stood in magnificent isolation, whereas in reality it was often surrounded by parks and horticultural creations of comparable quality. Tom has eloquently pointed out that the estates and homes of less grand, local landowners helped create regional traditions with a unique style all of their own.10 It wasn’t just that earlier traditions remained popular with many people, but sometimes innovations, which the textbooks would have one believe were universally and rapidly adopted, actually failed to find acceptance in certain areas. For instance, the new and characteristically ‘English’ landscape parks of the second half of the eighteenth century failed to catch on in Hertfordshire, where formal plantings of avenues and rides were laid out in the 1760s at major houses such as Cassiobury, Ashridge and Moor Park.11 Such geometric features belonged to an earlier era and went very much against the ‘natural’ spirit of landscape designers, such as Brown or Repton.

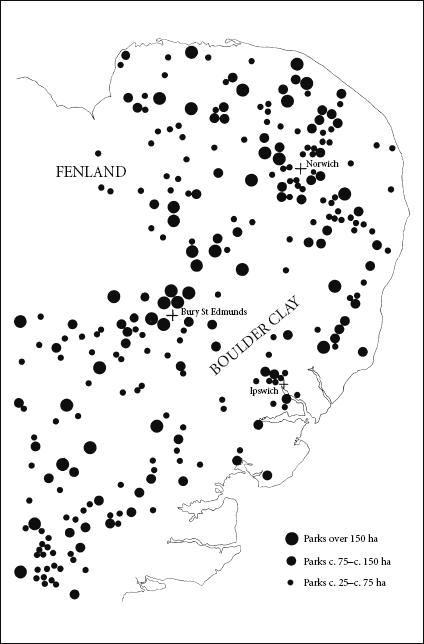

FIG 5 A map showing the distribution of landscape parks in East Anglia in the late eighteenth century.

We ignore these smaller parks and gardens at our peril if we want to create a true picture of the past that is not just based on a few well-known and very grand places. Such information will be invaluable when we come to interpret the remains of lost parks and gardens threatened by the immense expansion of housing that we are told will happen when the current economic downturn ends. Take one example: the large number of parks created in East Anglia in the late eighteenth century. Their quantity is impressive and their distribution pattern very informative.

There are, for instance, very few parks in the Fens, which were then plagued by endemic malaria and were characterised by numerous small landholdings. The heavy clay lands of Suffolk were also poorly emparked, but there were large parks on the poor, sandy soils of Norfolk’s Breckland (north of Bury St Edmunds, mostly around Thetford), where prominent families had owned hunting estates since the Middle Ages. Another interesting development was the proliferation of small parks around the increasingly prosperous urban centres of Norwich, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and south Essex, which was already feeling the influence of London.

I mentioned that it was possible to discern distinctive regional styles and one of the best of these is the use of canals in parks and gardens of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries in Suffolk. It is debatable whether this was a result of the area’s proximity to the influence of the Low Countries or reflected the suitability of the heavy, water-retentive clay soils that had been widely used for constructing moats in the Middle Ages. It is, of course, entirely possible that some people in the area simply created their own traditions of garden design as a conscious reaction to the increasing influence exerted by London fashions and popular designers like ‘Capability’ Brown, which many independent local landowners resented.12

We tend to think that the great parks and gardens were the product of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Enlightenment, with perhaps a few Tudor excesses such as Hampton Court, Hatfield and Burghley Houses to point the way forward. In reality, however, members of the upper echelons of medieval society were showing off their power and influence by constructing staged and elaborate approaches to their castles, and by fashioning their own landscaped parks.13 A particularly fine example is to be found on the approaches to the now ruined castle at Castle Acre, in Norfolk. This involved the redirection of a Roman road in the mid-twelfth century, by way of a newly founded Cluniac priory. Even when driving these narrow rural lanes today, this circuitous diversion, which was only done to impress visitors with the family’s piety, still feels distinctly odd.14

By the same token, we also tend to see ‘agri-business’ and industrial farming as rather unpleasant and ultimately unnecessary creations of the later twentieth century, but, again, the reality is rather different. The rapid growth of Britain’s population throughout the nineteenth century meant that the additional mouths had somehow to be fed and although imports could (and did) help to meet the shortage, in pre-refrigeration times the majority of food, especially of milk and meat, had to be produced at home. And here the well-laid-out model farms of the large rural estates were to play a crucially important role.

We will see in Chapter 5 that the monuments to Britain’s industrial past have been cared for and cherished since the subject of industrial archaeology first emerged from the shadows back in the 1960s. But their rural equivalents have only very recently received anything like their fair share of recognition – and almost too late, because numerous farm buildings of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are now becoming rather tatty and even derelict, simply because farmers in the twenty-first century are finding the money for their maintenance harder and harder to come by.15 A proportion has been saved for posterity by conversion to office or light industrial use, but sadly these remain a minority. The rest are quietly slipping into neglect and disrepair.

The great landed estates that were such a feature of the countryside from the seventeenth to the earlier to mid-twentieth centuries have, of course, left us superb country houses, parks and gardens.16 But these were essentially the cherries on the top of the cake. They were the obvious symbols of power and success, but much of the money needed to build and maintain such grand edifices came from the land surrounding them, which therefore needed to be efficiently farmed. And make no mistake: some of the estates could be very large indeed: the Census of 1871 shows that estates of the Duke of Bedford in his home county comprised a staggering 35,589 acres (14,408 hectares).17

By any criteria these estates were major businesses and they needed to be well run. They also had a huge influence on the development of the countryside and of rural communities – a role that has recently been recognised by historical archaeologists.18 But this was also the period when educated people had learned the lessons of the Enlightenment. They were not simply concerned with making money, but needed to establish and maintain their place in society, while at the same time demonstrating their good taste. It was a period, too, when growing urban industries could provide alternative sources of employment for rural people. So for these and other reasons, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw the construction of a series of model farms, the majority of which (as we saw in the previous chapter) were built as partnership ventures between entrepreneurial tenants and their estate landlords.

The slide into disrepair of so many estate farms has happened quite slowly, and bodies such as English Heritage have been able to anticipate events by carrying out surveys of model farms which have given rise to specific reviews and an excellent overall synthesis by the leading authority on the subject, Susanna Wade Martins.19 I have to say that, although I was aware of changes in the design of modern and early modern farm buildings, I was not able to discern any obvious pattern, apart from a general progression from small to large and also from decorative – even whimsical – to the more businesslike and severely functional buildings of Victorian high farming.

I mention whimsicality because sometimes farms occurred within sight of a carefully arranged view from a landscaped park, in which case they needed to be camouflaged to resemble a suitably romantic Gothic pile.20 Susanna gives several examples of these, one of which, illustrated in the pages of the Gentleman’s and Farmer’s Architect for 1762, actually includes corner towers that appear to have been reduced by artillery fire.21 My own favourite is the disguise of a range of farm buildings overlooking the great park at Stowe, Buckinghamshire, which have been made to resemble the turrets and battlements of a not very convincing medieval castle, which looks particularly odd – rather like a brick-built film set – when viewed from the modern road, which passes by on the ‘wrong’ side.