Полная версия

The Birth of Modern Britain: A Journey into Britain’s Archaeological Past: 1550 to the Present

The evolving patterns of farmyard layout are important as they illustrate the changing attitudes and outlook of the great landowners, and those who served and advised them. Sometimes, but not always, these shifts in emphasis mirror developments in the design of the great parks and gardens they helped to finance. More often than not, however, they reflect wider changes in the worlds of politics, trade or economics and latterly, too, of agricultural science. The recent survey of model farms by English Heritage has revealed that four broad phases can be discerned, beginning with the philosophy of ‘Improvement’ whose underlying principles could be defined as beauty, utility and profit. This phase, which I’ve discussed in Chapter 1, lasted from 1660 until 1790 and was followed by one of ‘Patriotic Improvement’ (1790– 1840). During these years farming and profitable estate management were seen as patriotic duties at a time when Britain was often at war with France, and food prices generally remained firm. George III set an example to all by employing the well-known land agent Nathaniel Kent to manage the farms and other resources of Windsor Great Park profitably.

The third phase (1840–75) was characterised by ‘Practice with Science’ and coincides with the time of Victorian high farming. The final phase, ‘Retrenchment’, from 1875 to 1939, saw estates hit by the collapse of prices and the farming depression of the 1870s. This was a result of many factors, including the import of cheaper food, especially grain, shipped in bulk from overseas. It could also be seen as a much-delayed after-effect of Peel’s repeal of the protectionist Corn Laws of 1846.

In the 1850s and 1860s, British farming was able to cope with the freed-up market, but the large-scale importation of grain, made possible by the introduction of larger ocean-going vessels from the 1870s, caused major problems. After that, British farming entered a prolonged recession which continued, with a few relatively minor ups and downs, until the Great Depression of the 1930s, followed by the Second World War, when many of the great estates started to disintegrate – a process that was hastened in the post-war years by the introduction of death duties and other taxes on inherited wealth.

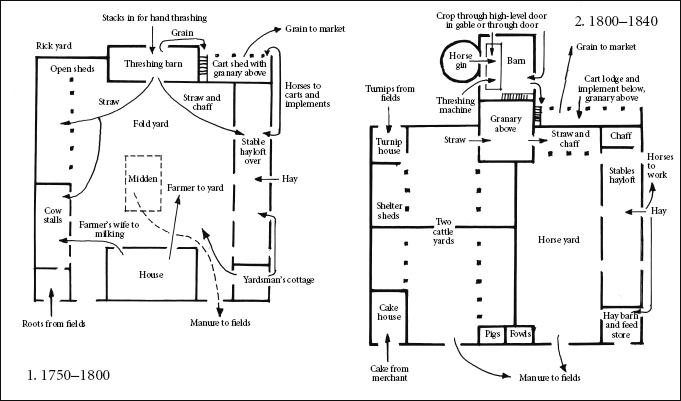

This brief history of the development of later post-medieval estates could readily have been derived from historical sources alone, but what makes the recent survey of model farms so important is the large number of buildings that were measured and photographed right across England. The owners and workers were also able to provide the surveyors with information on how the different spaces were actually used within living memory. The result is a hugely important body of information which will undoubtedly form the basis of many studies in the future. But to give an idea of its general scope, they have provided English Heritage with brief county-by-county summaries of the principal estates, their best surviving farms and a glimpse of their histories.22 It makes fascinating reading as it stands, but the information behind it has also been used to construct four plans of typical farm layouts between 1750 and 1900, which I have reproduced here.23

All farm buildings, whether on large lowland estates or on small upland family farms, were constructed to provide shelter for livestock and to keep stored crops dry. They could also be used for threshing and other crop-processing tasks, and for the preparation of fodder (e.g. hay and straw) or feed (e.g. grain or turnips) for livestock. Other uses, such as specialised milking parlours, became increasingly popular later, especially in farms near large cities. One additional important function of a post-medieval farmyard was the converting of chemically ‘hot’ raw animal dung to benign, nutrient-rich manure for spreading on fields. This is a biological process that involves the storage of the material in a muck heap, or midden, in well-drained conditions, with or without a roof.

The earliest estate farms (1750–1800) were based on a courtyard plan with the house on one side and the barn opposite. On either side of the yard were stables and animal sheds with a muck heap at the centre of the yard. In this layout the house was an integral part of the farmyard as nearly all the labour, including threshing, was carried out by hand. In the next period (1800–40) the house has been completely detached from the yard, which has now become E-shaped, with a main two-storey threshing barn at right angles to the long range, from which sprang three parallel ranges (the arms of the ‘E’), where the horses and livestock were housed and fed. By this period many tasks were now mechanised, the power being provided either by horses or water. On many farms you can still spot the circular walls that surrounded a horse ‘gin’, where a horse or horses pulled or pushed a long arm, rather like a treadmill.

FIG 6 The layout of typical model or estate farms in England around 1750–1800 (left) and 1800–1840 (right).

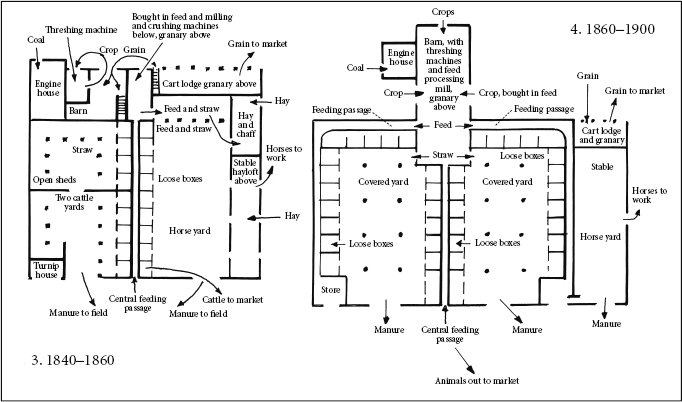

FIG 7 The layout of typical model or estate farms in England around 1840–1860 (left) and 1860–1900 (right).

The plan of earlier Victorian estate farms (1840–60) remained essentially E-shaped, but now the layout had become increasingly industrial, with the functions of the barn moved closer to the livestock accommodation. By this time, too, imported feeds were becoming more important and machinery previously used to thresh home-produced corn was now used to process the new feeds. The fattening of livestock was also becoming better understood and animals were separated into individual stalls or smaller groups to prevent undue competition. Some of these stalls were serviced by way of a central feeding passage. These better designed and more compact yards were often roofed over to keep the middens dry, thereby speeding up and improving manure production.

In the final decade of Victorian high farming the builders of model farms turned their attention to livestock units when the earlier plan with a central barn at right angles to the other ranges reappeared, but this time the building functioned more as a feed-processing factory than a barn. In the late nineteenth century (1860–1900) all livestock was housed in stalls that were conveniently accessed by feeding passages. By this time labour was becoming more expensive and routine tasks such as feeding and mucking out were made as straightforward as possible, with feed in some instances being moved on trolleys and tramlines. The two central covered yards continued to be used for the maturation of muck into manure.

I can well recall sitting down to watch television on freezing winter nights when I was working at the Royal Ontario Museum, in Toronto, in the 1970s. Inevitably I sometimes felt rather homesick, which is probably why I watched repeats of all the episodes of Upstairs, Downstairs, a British TV series then being shown in Canada. I still think it was a fabulous series, beautifully researched and acted, and quite rightly hugely popular in Britain and North America. What I didn’t realise at the time was how remarkably archaeological the approach of the programme makers was, because they showed precisely how a great house was serviced and operated; this is not something one can generally read about in novels of the period, which tended to focus on the goings-on of the great and the good ‘upstairs’.

Television costume dramas have played an important part in the way that country houses are now shown to the public, with greater attention at long last being paid to the servants’ hall, the cellars, the kitchens and the butler’s pantry – not to mention the stables, carriage house and scullery. I for one would far rather look at a nineteenth-century kitchen range than a display case stuffed with Meissen porcelain – or, indeed, some luckless volunteer dressed up rather awkwardly as a Georgian ladies’ maid or a footman. I find that the practical things of daily life, such as tools and implements, especially if they still retain the patina and scars of repeated use, have a power to re-create the past, something that fine objects often lack.

The service ranges of large country houses were where the work took place. Often they were of comparable size to the space occupied by the family itself. It was not uncommon to find that several entire storeys, or sometimes complete wings, were occupied by the domestic servants and there was a network of stairs and passages that allowed them to go about their daily duties without bumping into anyone from the employer’s family. In larger houses the world ‘below stairs’ was indeed a world – and, as Upstairs, Downstairs showed so well, it was often as vigorous and exciting as that in the great drawing rooms ‘upstairs’.

If we examine the shapes and layout of these domestic ranges they can tell us a great deal about the social changes that were taking place in early modern times, especially if the excavations are on a reasonably large scale. A few small slit trenches might establish construction dates and that sort of thing, but one needs an entire range to be stripped and excavated if one is to understand how it was used. Happily, this is exactly what has happened in a fine Jacobean (formerly) country house now surrounded by the streets and dwellings of modern Birmingham. I had been aware for some time of the presence of a great house as one drove towards the city centre on that long stretch of raised road south of the M6, but, to be honest, I had dismissed it as something Victorian – which I’m now aware was an error on my part. But I’ve been back there since and taken a closer look, and to my surprise I was completely wrong. Aston Hall really is rather special: a large three-storey Jacobean house with prominent turrets and banks of chimneys, elevated on a natural terrace and still dominating the landscape, which, as I’ve said, consists mainly of modern urban buildings. The notable exception is the village of Aston’s medieval parish church nearby, and a small park, which manages to retain a reminder of the area’s once rural surroundings.

Today Aston Hall is run by Birmingham City Council Museums and Galleries and in 2009 it reopened after a £13 million programme of repair and refurbishment, which included extensive excavation.24 As the digs were a part of a major project they took place on a suitably large scale. Anything else and the results would inevitably have proved less conclusive and, of course, far less exciting.

The house itself was built between 1618 and 1635 by Sir John Holte, probably to the designs of John Thorpe, and it represents a clear statement of the new relationship between master and servant that had developed in post-medieval times.25 Had Aston Hall been built in the early fifteenth century the kitchens, pantries and other domestic rooms would have been inside the main buildings, together with servants’ accommodation which was not kept particularly separate from that of the owner’s family. Although the family would have dined at a separate high table, when eating on public occasions few efforts were made in the Middle Ages to separate the lives of the domestic staff from those they were serving. All of that changed quite rapidly in the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when new houses were designed to keep the activities of resident domestic staff separate from the daily lives of the owner’s family.

In new houses of the seventeenth century, domestic staff would have been housed in their own quarters in either a basement or a separate wing and additional sleeping space would have been provided in the (often rather draughty) attics. For the first time, these various rooms would have been linked by their own network of stairs and passages which meant that the owner’s family need never contact a servant unless, that is, he or she wanted to. Similarly, although the kitchens remained in the main house (but very much within the domestic area), the rooms where other household activities took place, such as the brewhouse, stores, washing rooms, bakehouse and dairy were removed either to separate wings, or (as at Aston Hall) an altogether separate Service Range.

The Service Range at Aston was very carefully positioned at the foot of a slope some twenty-five metres from the main house, and largely concealed by a tall brick wall. It is interesting that Dugdale’s 1656 view of the house uses perspective to give the impression that the Stable Range is even more removed and it entirely conceals the Service Range. Indeed, guests at the great house need never have been aware that the Service Range even existed. The main house and its North Wing formed one side of the domestic Stable Court, which was open to the west but enclosed to north and east by the Service and Stable Ranges. Inside the North Wing were the kitchen, the wine and beer cellars, scullery and servants’ sleeping quarters on the upper floor. This arrangement meant that no guest or member of the owner’s family need ever have to look out onto the Stable Court.

In anthropological terms the increasing separation of ‘those upstairs’ from ‘them downstairs’ might be seen as hierarchical, but the developing social hierarchies did not stop there. Below stairs, and fully recognised by the owner’s family, we see an emerging ranked society in which senior household servants, such as the butler, who waited directly on the owner, the cook and housekeeper and others were accommodated within the domestic apartments of the main house, which at Aston Hall were in the North Wing. Junior servants would have to find their sleeping spaces in the Service Range or attics.

I must have read thousands of excavation reports and a high proportion of them have been almost unendurably dull. This sad situation has arisen because over the past twenty or so years, ever since changes in planning law made it compulsory for developers to pay for archaeological examination of sites they were about to destroy, large numbers of quite insignificant excavations have had to take place – and then reports be written up. In theory – and in practice, too – these small projects add to our sum of knowledge about a given region and in time they start to produce coherent stories. But it is not a rapid process and much of the work is, at best, humdrum. That is why most archaeological contractors leap at the chance of doing larger projects, where the element of new research is greater and where it might be possible to write a good, original report. And that is exactly what happened after the Aston Hall excavations, where the team from Birmingham University have combined evidence from the trenches with historical research to produce an absolutely fascinating story. I’ll be quite honest: before I started, I thought a paper about a dig on an abandoned service range would make extremely dry reading, but I was completely mistaken.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.