Полная версия

The Birth of Modern Britain: A Journey into Britain’s Archaeological Past: 1550 to the Present

When I learned about the manorial system at school I gained the impression that, once in place, it remained there, pretty much unaltered. This is perhaps where our views have changed the most. We now realise that it was a dynamic system that was modified from one area to another through time, depending not just on the local soil and climate, but on social factors, such as the wealth, power and influence of landlords. We have also discovered that the once clear distinction between the collective Open Field farms of the nucleated landscapes could not necessarily be distinguished from the individually owned farms of the woodland landscapes. In other words, there was Open Field farming in ‘woodland’ areas and vice versa.8 So although the very broad distinction into the three provinces can still be said to hold true, it simply cannot (and must not) be used to predict what one might discover in a randomly selected tract of landscape.

These warnings become even more important from the fourteenth century, when the population was massively reduced following food shortages and the terrible impact of successive waves of plague that then continued right through to the seventeenth century. Although, as I have said, the feudal ‘system’ never really took a firm hold in Britain, even after the Norman Conquest, most of the ties and obligations that did exist began to slip when the rich and powerful could no longer rely on a large, docile and cheap workforce.9 From the fourteenth century peasant farmers and working people realised they were no longer in a buyer’s market, especially when it came to the negotiation of their land tenure and labour contracts. In the western ‘woodland’ regions this less restricted climate began to give rise to a new, dual, rural economy where the families of smaller farmers developed a second string to their bow, which was usually based around something to do with the land, such as spinning and weaving, or coal-mining in places such as the Forest of Dean where coal was readily accessible. These dual economies varied from region to region, but as we will see later they played a crucial role in the development and growth of industry in these areas.

So for practical purposes, we can see the Middle Ages in rural Britain drawing to a close from the mid-fourteenth century onwards, for which reason the following three hundred years have been described as an age of transition in which political and religious changes did not necessarily happen smoothly. But viewed in the longer term they did indeed happen, and what is more, the evidence they left behind can be traced both on and in the ground, for example in the way that people changed their attitudes towards rites of burial and memorial and even in more mundane aspects of life, such as their choice of domestic pottery.10 The effects of these continuing processes of change, however, only became highly visible during the Reformation (c. 1480–1580), a period which saw the rise of Protestantism and the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

I think I can understand why the version of history taught at school paid so much attention to the Open Field farms of medieval Britain. It was, after all, a very different way of doing things and it also gave teachers a chance to discuss the social ties and obligations of feudalism, while at the same time it brought the Church, monasteries, great landowners and manorial courts into the story. I can well remember being struck by the mystery and romance of the times, supposing myself a wandering troubadour strumming a lute at the feet of beautiful maidens. Although on second thoughts, this makes me think I wasn’t quite so young as I once imagined. Anyhow, the period that followed was, if anything, rather more fascinating, because it witnessed social and economic developments that are still affecting British life.

There can be no doubt that in many rural areas, especially in the old Central Province of the English Midlands, the post-medieval period got off to a shaky start. I’ll have more to say about this later, but in essence the general population decline of the later fourteenth, fifteenth and earlier sixteenth centuries, which was ultimately brought about by successive waves of plague, left its mark on early modern towns and villages in the countryside. However, things were about to improve, slowly at first, but then with gathering rapidity.

At this point I must add a quick note about the process known as ‘enclosure’, which I will discuss in greater detail shortly. When we discuss the end of the Open Field system we find it replaced by enclosure. Used in this way the word refers to a change in landownership where several owners are replaced by one. I think many people still labour under the misapprehension that the manorial system and Open Field farming both came to an abrupt end some time between the Battle of Bosworth (1485), which saw the effective end of the Wars of the Roses, and the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when a near-tyrant king effectively pulled the rug of power from under the feet of the Church. At least that is how things appeared. We now realise that both society and landscapes actually take rather longer to modify in so drastic a fashion. As I noted earlier, the seeds of change were planted in the mid-fourteenth century, but that was just the beginning. In many parts of Britain, especially in the Midlands and eastern parts of England, Open Field farms continued through the sixteenth century, but by its end nearly half had succumbed to enclosure. By 1700 three-quarters had been enclosed. So when statutory or parliamentary enclosure (see below, p. 38) began in earnest in the later eighteenth century only a quarter of the Open Fields required enclosure – and of course today we are left with just a single surviving Open Field parish, at Laxton, in Nottinghamshire.11

We have just seen that, although the dissolution of the great monastic house of Glastonbury had an immediate effect on landownership at Shapwick, the direct effect on patterns of farming was relatively slight. Only somewhat later, when the process of emparkation had got under way, did the longer-term results of the shift in landownership become evident in the landscape. In some places, however, the Dissolution had a sudden and dramatic effect. And nowhere was this more evident than in the Fens where a vast area of new land was drained, largely through the good offices of the Earls and then the Dukes of Bedford who had acquired money plus the vast estates of Thorney Abbey during the Dissolution; this provided the basis for the region’s prosperity from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries.12 We will see shortly that drainage, mostly to improve pasture, rather than to provide new arable land, was to become an important feature of the second phase of post-medieval farming improvements of the early and mid-eighteenth century.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries we see a gradual move away from the Open Field system of farming towards a more complex set of regional patterns which better reflected local soil types, transport networks and what today we would call marketing opportunities. It was never simply a matter of finding the best soil to grow a particular crop. Take, for example, the vegetable farms around Sandy in Bedford. Here, as any vegetable gardener could tell you, the Ouse Valley terrace gravels in their natural state are rather too light and well drained to grow the top-quality brassicas, such as the Brussels sprouts that are still such a noted speciality of the region; and it was only the addition of much manure and fertiliser, together with the ready availability of the vast market provided by a rapidly growing London population, that allowed the vegetable trade to develop successfully.

Plotting the development of early modern (1550–1750) farming has been a process which has owed much to economic historians and geographers, such as Joan Thirsk and Eric Kerridge, and without the basis of their pioneering research the recent work of more archaeologically orientated scholars, such as Susanna Wade Martins and Tom Williamson, would not have been possible. Today agricultural history is going through a very exciting period indeed. Thanks to people like Joan Thirsk we have long since abandoned some of the rather simplistic ideas – I almost said ideals – exemplified by terms such as the Agricultural Revolution and are now in the throes of creating a new history of rural Britain, based more on facts unearthed from survey and from detailed examination of sources such as estate records, than on over-arching concepts that sound good, but actually mean little. I shall return to the evidence for the timing of that supposed agricultural ‘revolution’ shortly.

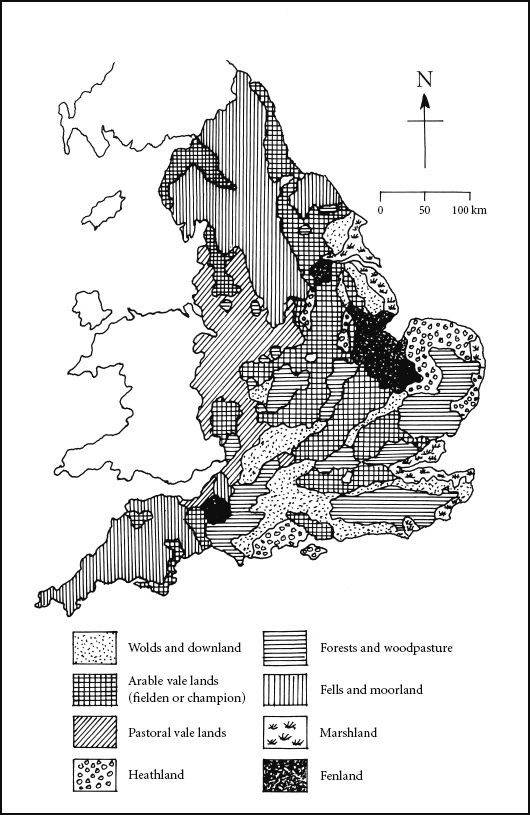

In the later 1950s and 1960s Kerridge, followed in the seventies and eighties by Thirsk, together with other economic historians, began to produce maps that plotted the extent of early modern agricultural specialisation in England. These maps were actually plotting complexity, so they themselves can be daunting to read. But I make no apologies for that. I don’t think it’s necessary to grapple with precise details of individual regions, unless, of course, one has a specific interest, but the overall picture is nonetheless important, so I have reproduced Thirsk’s simplified general plan here. This map was based on two more complex maps, the first of which showed English agricultural regions in the century and a half from the start of the sixteenth century (actually from 1500 to 1640); the second illustrated how the situation developed in the following century or so, from 1640 to 1750.13

The two detailed maps are, however, important because they illustrate well the growing complexity of the post-medieval farming landscape. Both show a sharp distinction between mixed farming (arable and pasture) and pasture farming, which in turn is subdivided into woodland pasture and open pasture. All three main categories are then further subdivided into different varieties of mixed, woodland and open pasture farming. In the earlier map there is still a broad swathe of mixed farming that extends if not quite from Somerset, then from the south, through the Midlands, Lincolnshire, most of east Yorkshire and up to County Durham and Northumberland. Although this zone has altered somewhat from the Central Province of the earlier Middle Ages it is still broadly recognisable, despite now extending into parts of Norfolk, Kent and Essex. By the time we get to the second map, the areas of mixed farming have slipped south and east, largely departing from the medieval pattern.

FIG 2 Map showing the farming regions of early modern England (1500–1750).

The principal difference between the two maps is the far greater complexity of the second, later, one. Take just two regions. Post-medieval innovations are perhaps most marked in my own area, the Fens, which are shown in the earlier map (and indeed in the simplified one reproduced here) as a single region, given over to open pastoral farming involving stock-fattening with horse-breeding, dairying, fishing and fowling. After 1640, and the first phase of widespread, though still incomplete drainage, the earlier style of farming has been confined to a narrow area of marshland around the Wash, whereas the bulk of Fenland now comprises two broad areas, one to the north of silty soils that are devoted to stock- and pig-keeping, fattening, and corn-growing, while to the south the more peaty land is still mainly used for grazing and, of course, no cereals are grown. Incidentally, somewhat later, in the earlier nineteenth century, following the introduction of steam pumps, we see a further near-complete transformation of this particular landscape.

In Kent and Sussex, although the distinctive oval shape of Wealden geology continues to exert an influence (as indeed it does to this day), the varieties of farming become very much more complex in the period covered by the later map. This in part reflects the arrival of entirely new ideas, such as the introduction of fruit orchards and hop fields. The point to emphasise here is that early modern farming was a dynamic and increasingly specialised business which was becoming ever more dependent on the growth of towns and cities. Nowhere was this more important than around the two principal capitals of Edinburgh and London, which by the end of the Middle Ages had come to dominate the region and countryside around them. The areas peripheral to the large towns and cities not only provided food and raw materials for the growing urban population, but perhaps as significantly, they also provided a constantly renewing pool of labour, especially following the recurrent waves of plague that bedevilled many of the larger cities in later medieval and early post-medieval times.

We are still in the realms of general economic history and I want soon to come down to earth and see how individual farms and fields were adapted as economic conditions changed around them. But first we must briefly examine the idea of the ‘Agricultural Revolution’ which is traditionally thought to have happened between 1760 and 1830. A slightly longer view (1700–1850) would allow the main events to have happened in three stages, the first stage being completed sometime around 1750–70. These initial developments involved the introduction of new crops, especially root crops such as turnips, which we now know were pioneered not in Britain, but in the Low Countries, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.14

As early as 1600 growing Dutch influence had seen the introduction of cabbages, cauliflowers, turnips, carrots, parsnips and peas to market gardens around London. Turnips were introduced to East Anglia from Holland in the mid-sixteenth century and they then formed an important element in the famous Norfolk four-course (crop) rotation of wheat, turnips, barley, clover and/or grasses.15 The Norfolk four-course rotation required the land to lie fallow for less time (if the land had become too depleted the final crop of clover and/ or grass could be extended for an additional season).This cycle of crops produced more grazing and fodder in the form of turnips which in turn resulted in more and fatter livestock and, perhaps just as important, more manure to be spread on the fields. I also believe it must have given livestock farmers greater security and peace of mind.

As I have discovered to my cost, in seasons when late winter rains continue into March and April it can be unwise to turn young animals out onto muddy fields and waterlogged pasture. As any livestock farmer knows to his cost, fast-grown grass is deficient in minerals and both ewes and lambs can soon develop ‘grassland staggers’. So you house them for longer, but the next thing you discover is that the hay and straw they have been happily consuming over winter simply lack the nourishment that growing lambs so desperately need and soon they start to look thin, lanky and bony. They also lack vigour and don’t rush about in that wildly enthusiastic, but completely mad and pointless fashion that can make them so endearing. In such situations today one buys in (expensive) supplements usually in the form of ‘cake’, but as farmers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries knew only too well, the sprouting heads of growing parsnips and the roots themselves were almost equally nutritious – and a lot cheaper.

Perhaps the most significant reform that enabled changes to happen in the British countryside was the concept of enclosure. Having said that, we shouldn’t go overboard in our enthusiasm. For a start, huge areas of the later medieval landscape had never come into collective ownership and large estates, both private and owned by ecclesiastical authorities, were already in existence in the Middle Ages. As we saw at Shapwick, the latter could readily be transferred to private ownership. Many of the small farms of the two later medieval woodland provinces began to rationalise their holding first in later medieval times and with increasing rapidity from the sixteenth century. This was enclosure, but not carried out by individual Acts of Parliament, as was to happen much later. It has been termed ‘enclosure by agreement’ and it also involved the dismantling of Open Field farms and the taking in of common land.

Although we should record that in many instances the ‘agreement’ was imposed by a rich landowner and his lawyers (and this is particularly true in the case of the many large enclosures of Tudor times that were created to make vast, open sheep runs). The main era of enclosures by agreement was in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and today these landscapes can still be seen to cover large tracts of countryside in the west and south-west of England, especially in Devon and Cornwall.16 As a general guide, early enclosures of this sort often preserve features of earlier landscapes in their layout, such as the gentle reversed S boundaries of abandoned Common Fields. That distinctive shape, incidentally, was a ‘fossil’ left by years and years of strip ploughing, where the plough teams had restricted space to turn at each end, thereby leaving a slightly sinuous furrow.17

Modern landscapes that arose through early enclosure, or enclosure by agreement, and by means of parliamentary enclosure appear very different. Not only do the early enclosures incorporate previous features, such as those reversed S boundaries, but although they are generally square-ish or rectilinear, their fields certainly don’t follow a rigid pattern and it is usually obvious that they arose as a series of distinct, one-off agreements. As such they tend to follow the shape and ‘grain’ of the topography rather better than the later (often parliamentary) enclosures which were accurately surveyed in. As a consequence, in these later enclosures dead straight lines and right angles predominate. Although many would disagree with me, I still like these later landscapes which I find have a charm all of their own – maybe it’s because I grew up in them that I feel at ease there.

Parliamentary enclosure took place rather later in our story, generally in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Essentially it was a response to the increasing pace of enclosure by agreement in those areas of central and eastern England where the medieval Open Field system had left a complex legacy of sometimes quite large parishes with numerous smallholdings belonging to many tenant and owner-occupier farmers. In such complex situations agreement was often difficult or impossible. So the passing of individual Acts of Enclosure was seen as a way through these problems. In theory at least it was a fair and transparent system where the process of enclosure was overseen by a parliamentary commissioner who also saw to it that the land was surveyed and parcelled up by official surveyors. But there was much scope for potential abuse: for example, areas of common land and so-called ‘wastes’ (where nobody claimed actual ownership) had to be reapportioned among the landowners of the parish. And as so often happens, the actual results were rather different and by the end of the process the big estates had done very nicely thank you, while substantial landowners and rising yeoman farmers also generally increased the size of their holding; more importantly, these holdings were now arranged more rationally and could be farmed much more efficiently. But small farmers often ended up proportionately worse off than their larger neighbours.

The first Parliamentary Act of Enclosure was passed in 1604 and in the eighteenth century these rapidly became the dominant method of enclosure, with some four thousand Acts passed between 1750 and 1830, covering about a fifth of England’s surface area.18 The process continued through the nineteenth century. Apart from a contribution from the taxpayer, most of the cost of parliamentary enclosure was paid for by the larger landowners and this was probably why they tended to fare better than smallholders. It’s not hard to work out why. If one bears in mind what one learned as a child about the ratio of surface to volume, the men with the smallest holdings had proportionately the longer boundaries. These then had to be re-fenced and re-hedged at their owners’ expense. In many instances this was to prove too much so they sold out to their larger neighbours.19

In the English Midlands parliamentary enclosure must be considered successful, but that cannot be said for everywhere, even in England. In upland areas of northern England, for example, parliamentary enclosure often ignored topography and was sometimes frankly irrational. If anything, it made efficient farming more difficult.20

In Scotland enclosure was by agreement, or latterly by imposition of powerful landowners. In the Lowlands the process was well under way in the 1760s and 1770s and in the Highlands towards the end of the century, where they became known as the Highland Clearances; these enclosures often involved the clearance of entire rural populations to make way for sheep pasture and later for moorland game reserves. The Clearances continued late into the nineteenth century when huge numbers of people were either removed to new settlements often within the landowners’ estates along the coastal plain, or were sent abroad, principally to Canada. To give an idea of the scale of the Clearances, some 40,000 people were removed from the Isle of Skye between 1840 and 1880.21

I think it would be a big mistake simply to think of the earlier post-medieval period in terms of big all-transforming movements, such as enclosure. Many poorer rural people lived outside the world of what one might term legalised land tenure. Theirs was an existence where possession was nine-tenths of the law and nowhere was this more evident than in the less prosperous parts of upland, non-Anglicised Wales. Because these holdings were, at best, quasi-legal, they have left little by way of a paper trail. So to track them down, my old friend Bob Sylvester (who initially made his name by sorting out the medieval archaeology of the Norfolk Fens) has had to turn to archaeology.22

According to Bob, the traditional archaeological view of Wales was ‘a single undifferentiated upland landmass, appended to the western side of England’.23 Unfortunately, such attitudes made no allowances for the distinctive landscapes of Wales which often arose through the action of people and communities that were very different from those further east. One such distinctive feature has been termed ‘encroachment’.24 As the population of Wales began to grow from the later seventeenth century, and most particularly in the eighteenth and early nineteenth, impoverished landless people built themselves small houses and laid out smallholdings on the common land of the uplands, usually without the landowner (often the Crown) being aware. These people were often given moral and practical support by local parish councils who did not like seeing perfectly good land being left to stand idle. Sometimes landowners themselves encouraged such encroachment, especially if they were looking for labour to exploit coal and other mineral resources in these otherwise under-populated upland regions.

Informal settlements of this kind are fairly distinctive on the ground. They consist of a seemingly random scatter of small single-family households, within a couple of acres of land. Sometimes the more successful homesteads acquired the additional outbuildings of an upland farm and the various houses are usually served by a single, meandering lane. Encroachments are by no means confined to the uplands and can be found in valley floors, especially on land that was once poorly drained and uncontrolled, such as many of the tributary valleys of the Severn along the border country of Montgomeryshire and Shropshire.25

Despite local difficulties of the sort we have just discussed, the rationalisation of the rural landscape brought about by enclosure of all types meant that farmers and landowners were now able to take practical measures to improve their land. In most cases this involved under-drainage, which was particularly effective in the clay lands of East Anglia, where huge areas were drained in the first half of the nineteenth century. Under-drainage involved the cutting, by hand, of a series of parallel, deep, narrow trenches containing brushwood, gravel, stone or clay pipes, these then emptied into ditches along the field’s edges, which in turn had to be deepened and improved. The work was often paid for by landowners.26 The other major innovation which has left a distinct mark in the landscape, mostly of western Britain (although it was tried without the same success in drier East Anglia, too), was the extensive ‘floating’ of land through the construction of artificial water meadows in the years between 1600 and 1900.27