Полная версия

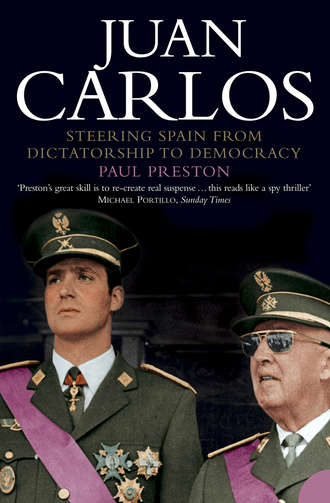

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

The delay in resolving Juan Carlos’s immediate future hardly mattered since, in the wake of his operation, he was in no fit state to be sent anywhere and spent the winter of 1954 convalescing in Estoril. Nevertheless, Gil Robles was appalled to learn that, while awaiting the reply to his letter of 23 September, Don Juan had permitted negotiations with the Caudillo to continue through the mediation of the Conde de los Andes, the recently appointed head of Don Juan’s household. However, these talks would take place in the shadow of other events, and unexpectedly their eventual fruit would be the Caudillo’s agreement to a private meeting with Don Juan to discuss the details of the Prince’s education in Spain.48

Behind his apparent confidence, Franco still had concerns about monarchist opposition. Already, in February 1954, he had received a visit from several generals, including the influential Captain-General of Barcelona, Juan Bautista Sánchez. To his outrage, the generals touched on the forbidden subject of his eventual death and politely asked if he had made arrangements for the monarchist succession thereafter.49 Then, while still contemplating Don Juan’s letter of 23 September, Franco was alarmed to be informed that the coming out of Don Juan’s eldest daughter, the Infanta María Pilar, had given rise to 15,000 applications for passports from Spanish monarchists who wished to travel to Portugal to pay homage to the royal family. Franco’s oft-repeated claims that there were no monarchists in Spain were severely dented. Twelve thousand applications were refused but 3,000 monarchists made the journey to Estoril for the celebrations held on 14 and 15 October. Along with the cars of aristocrats and senior Army officers there were also charabancs packed with significant numbers of the more modest middle classes.

The Caudillo’s brother Nicolás, the Spanish Ambassador to Portugal, was present at the spectacular ball given at the Hotel do Parque in Estoril, at which the great Amalia Rodrigues sang traditional Portuguese fados. He reported back to El Pardo about the warmth and spontaneous enthusiasm that had greeted the words of Don Juan when he spoke of his hope of seeing a Spain in which all were equal before the law and referred to ‘the Catholic monarchy which is above any transitory circumstances’. Nicolás probably did not mention that he had clapped furiously when Don Juan took to the dance floor with his daughter or that his wife, Isabel Pasqual del Pobil, had eagerly joined in the shouts of ‘¡Viva el Rey!’ Carmen Polo was quick to express her disgust to her husband when this was reported back to her.50 Franco’s fury was directed against the aristocratic guests, and he talked of removing the privilege of a diplomatic passport enjoyed by the highest ranking nobility, the grandes de España, ‘because they use it to conspire against the regime’.51

The strength of the monarchist challenge was further brought home to Franco in the course of limited municipal ‘elections’ held in Madrid on 21 November 1954, the first since the Civil War. They were presented by the regime as genuine elections because one third of the municipal councillors would be ‘elected’ by an electorate of ‘heads of families’ and married women over the age of 30. Enthusiastically supported by the newspaper ABC, there were four monarchists up against the four Movimiento candidates put up by the regime. The monarchists were harassed and intimidated by Falangist thugs and by the police. The Movimiento press network mounted a huge propaganda campaign that presented these elections as a kind of referendum. The entire issue was seriously mishandled, exposing as it did the farce of Franco’s claim that all Spaniards were part of the Movimiento. Monarchist publicity material was destroyed and voting urns were spirited away to prevent scrutiny of the count. Inevitably, official results gave a substantial victory to the Falangist candidates. It was clear that there had been official falsification and the monarchists claimed to have received over 60 per cent of the vote.52 At first, Franco was happy to believe that the municipal elections constituted an outpouring of popular acclaim for him. However, a stream of complaints from prominent monarchists and a threat of resignation from Antonio Iturmendi, the traditionalist Minister of Justice, made even the Caudillo begin to doubt the official interpretation of events. He was shocked when General Juan Vigón, now Chief of the General Staff, but still a fervent monarchist, told him that military intelligence services had discovered that the bulk of the Madrid garrison had voted for the monarchist candidates. He was appalled to hear Vigón stating that: ‘The regime lost the elections of 21 November.’ This indication that support was gathering for Don Juan compelled Franco to take action.53

Instructions were sent to Nicolás Franco in Lisbon to inform Don Juan that he was now ready to meet him. Since Franco had never had any doubts about the kind of education that he wanted for the Prince, there was, from his point of view, no need for a meeting. The boy’s personal needs were of no concern to him. His surprising agreement to meet the Pretender was merely a reaction to growing evidence of the strength of monarchist feeling within Spain. The encounter was to be no more than a propaganda stunt to neutralize that feeling. He had no intention of making any concessions. In his much delayed reply of 2 December 1954 to Don Juan’s September letter, Franco wrote in dismissive terms, limiting the agenda for the meeting. He made it clear that Juan Carlos had to be educated according to the principles of the Movimiento in order to be in tune with ‘the generations that were forged in the heat of our Crusade’. This was a matter on which, according to Franco, there could be no misunderstanding. If the Prince were not to be educated in this way, it would be better for him to go abroad, since: ‘the monarchy is not viable outside the Movimiento.’ Altogether better would be for the Prince to be educated in Spain under Franco’s vigilance.

It was an irony – and one that Franco was anxious to conceal from Don Juan – that the neutralization of the monarchists and the consolidation of his own plans for the succession were probably now his greatest concern. Hitherto, his most effective weapon in silencing Don Juan had been to conjure up successive revivals of the Falange. This also served to strengthen his argument to Don Juan that, as Caudillo, he could tolerate no restoration of the line that fell in 1931, but rather only the installation of a Falangist monarchy. However, the unexpected success of the monarchists in the Madrid ‘elections’ showed that the Falange was increasingly anachronistic while the monarchist option seemed more in tune with the outside world. The policies of autarchic self-sufficiency favoured by both Franco and the Falange had brought Spain to the verge of economic disaster. At the very least, it would be prudent to convince the royalists among his own supporters of his own good faith as a monarchist – hence the meeting. Don Juan and his supporters might believe that they would be discussing ways of hastening a restoration but Franco’s letter showed again that he would hand over power only on his death or total incapacity and then only to a king who was committed to the unconditional maintenance of the dictatorship.

It was clear that Franco saw the education of Juan Carlos as the preparation of precisely such a king. That did not necessarily mean that there was certainty as to the Prince’s eventual succession to the throne. Apart from encouraging the claim of Don Jaime and his sons, Franco now had another candidate nearer home. On 9 December, his first grandson had been born and his sycophantic son-in-law, Cristóbal Martínez-Bordiu, suggested changing the baby’s name by reversing his matronymic and patronymic. The formal agreement by a servile Cortes on 15 December to his name being Francisco Franco Martínez-Bordiu made the new arrival a potential heir to his grandfather. Alarm spread in monarchist circles that Franco planned to establish his own dynasty.54 This was exacerbated when the Conde de los Andes reported on the harshness of Franco’s tone during their negotiations on the agenda to be discussed in the forthcoming meeting between the Caudillo and Don Juan. Outlining his own plan for the Prince’s education, he had told the astonished count that: ‘If Don Juan does not accept such an education for his son, or his son does not agree to it, the Prince should not return to Spain and that will mean that he has renounced the throne and that I will consider myself free of any understanding with him.’ Pacón noted in his diary that a meeting was utterly pointless because he knew that nothing would make Franco deviate from the plan that he had laid out. He bluntly told Pacón, ‘If Don Juan wants his son ever to reign in Spain, he must submit to my wishes, which are for his own good and for that of the fatherland, by entrusting the boy’s education to me. It must be without interference from anyone and handed over only to people that I trust totally.’55

Don Juan set off for Spain by car on 28 December 1954. Franco left El Pardo at 8 a.m. on the next morning in a Cadillac and with a convoy of guards. Both were headed for a halfway point between Madrid and Lisbon – Navalmoral de la Mata in the province of Cáceres in Extremadura. Arriving in Spain that evening was an emotional moment for Don Juan, the first time that he had set foot in his homeland since his failed attempt to join the Nationalist forces in 1936. The meeting – at Las Cabezas, the estate of the Conde de Ruiseñada, Juan Claudio Güell, the Pretender’s new representative in Spain – lasted from 11.20 a.m. to 7.30 p.m. with a late lunch break. At the steps of the mansion, the ever-affable Don Juan greeted Franco cordially and had created a relaxed atmosphere by the time that they sat before a roaring fire. He felt confident, telling Franco that he had received thousands of messages of support from Spain including telegrams from four Lieutenant-Generals. However, such references to the current debate on the monarchist succession went over Franco’s head as relating to a far distant and theoretical future. This became clear when he began to talk of the possibility of separating the functions of Head of State and Head of Government. He would do so only, he said, when his health gave out, or he ‘disappeared’ or because the good of the regime, with the evolution of time, required it, ‘but, as long as I have good health, I don’t see any advantages in change’.

Franco was clearly at his ease, talking without pause or even a sip of water, and he proceeded to give Don Juan an interminable, rambling history lesson. Don Juan commented later that it was like listening to an obsessive grandfather boasting about his past. In fact, Franco’s reminiscences about his own military exploits could be seen as a sly attempt to humiliate Don Juan, who had not been allowed to fight in the Civil War. Efforts by Don Juan to get a word in edgeways and turn the discussion to the timing of the transition to the monarchy and the terms of the post-Franco future met with a frosty response. Franco did not hesitate to criticize many prominent monarchists as drunks and gamblers, accusing Pedro Sainz Rodríguez, about whom he had the most neurotic delusions, of being a freemason. When Don Juan praised Sainz Rodríguez as a faithful counsellor, in whom he had complete confidence, Franco replied, ‘I have never trusted anyone.’

Don Juan’s suggestion of the introduction of freedom of the press, an independent judiciary, social justice, trade union freedom and proper political representation merely reinforced Franco’s conviction that he was the puppet of dangerous aristocratic meddlers who were probably freemasons. Through the impenetrable and self-satisfied verbiage glimmered the Caudillo’s message. As he had already informed the Conde de los Andes: if Don Juan did not bow to his demand that Juan Carlos be educated under his tutelage, he would consider it as a renunciation of the throne. The needs, let alone the wishes, of Juan Carlos simply did not enter into the debate. Faced with Franco’s ultimatum, Don Juan thus agreed that his son be educated at the three military academies, at the university and at Franco’s side. However, he made it quite clear that none of this constituted a renunciation of his own rights. With the greatest reluctance, Franco accepted an anodyne joint communiqué whose terms implicitly, if not explicitly, recognized the hereditary rights to the throne of the Borbón dynasty. It was a minor victory for Don Juan that his name should appear alongside that of Franco.56

The joint communiqué aside, Franco had made no real concessions about a future restoration, or rather installation, as he called it. Nevertheless, the theatrical gesture of meeting Don Juan had, for the moment, drawn the sting of the monarchists and gave the impression that progress was being made. In his end of year message on 31 December 1954, he made it quite clear that he had conceded nothing to Don Juan. Using the royal ‘we’, he stressed that the monarchist forms enshrined in the Ley de Sucesión had nothing to do with the monarchy of Alfonso XIII. In the wake of the Las Cabezas meeting, the Caudillo was publicly affirming that he did not renounce his right, enshrined in the Ley de Sucesión, to choose a successor to guarantee the continuity of his authoritarian regime.57

Chatting with Pacón on the same day, Franco claimed that, at Las Cabezas, Don Juan had asked him if he thought it was necessary to abdicate in order that his son should have the right to inherit the throne. The exchange is not recorded in other accounts of the meeting. Indeed, those accounts suggest that what Don Juan actually said was that allowing his son to be educated in Spain did not constitute an abdication of his own rights. However, if it was not just wishful thinking on Franco’s part and Don Juan did ask the question, it could be interpreted as a ploy to force Franco to acknowledge the dynastic rights of the family. If, at Franco’s behest, Don Juan had abdicated in favour of his son, the Caudillo would have been committing himself to choosing Juan Carlos as his successor. It is unlikely that the question of abdication was raised in the precise terms recounted by Franco to his cousin. However the subject was raised, Franco’s reply, at least in his own account to Pacón, was a masterpiece of cunning.

Unwilling to reduce his options, the Caudillo allegedly replied, ‘I do not think that the problem of your abdication needs to be raised today, as we are here to discuss your son’s education, but since you’ve mentioned it, I must tell you that I believe that Your Highness rendered himself incompatible with today’s Spain, because against my advice that Your Highness remain silent and make no declarations, you published a manifesto in which you refused to collaborate with the regime and thus made yourself incompatible with it.’ He went on to talk of his ‘inclination’ to name as his successor a direct heir to Alfonso XIII. However, he also mentioned the strong temptation to nominate a prince from the Traditionalist branch of the family as a reward to the Carlists for their role in the Civil War and their loyalty thereafter. If the conversation took place as he claimed, it revealed his determination both to humiliate Don Juan and to keep open his own options.58

At the point at which Juan Carlos was about to return to Spain to be educated as a possible successor to Franco, his own interests as a human being were being sacrificed for a gamble. Franco could choose between a Carlist, Don Juan, Juan Carlos, Don Jaime or his son Alfonso and, perhaps, even the newborn Francisco Franco Martínez-Bordiu. Neither Juan Carlos nor his father can have been unaware of this. It must have been difficult for Juan Carlos not to feel like a shuttlecock in someone else’s game.

Before setting out for Las Cabezas, Don Juan had written to the Caudillo’s wartime artillery chief, General Carlos Martínez Campos y Serrano (the Duque de la Torre), asking him to be the head of the Prince’s household in Spain and thus charging him with the supervision of his son’s military education. Stiff and austere, the 68-year-old Martínez Campos was known for his dour seriousness, his acute intelligence and his sharp tongue. His marriage had broken down, and by his own admission, he had failed in the education of his own children. Even Franco was moved to comment: ‘God help the boy with that fellow!’59 Nevertheless, it was a choice that provoked considerable satisfaction at El Pardo. Until recently, Martínez Campos had, after all, been Military Governor of the Canary Islands. The general reported to Franco on 27 December. Pacón noted in his diary: ‘The Duque de la Torre is totally trustworthy and utterly loyal to the Caudillo.’ In fact, this was not entirely true – Martínez Campos was loyal and obedient, but he had considerable reservations about Franco personally and about the way in which he treated Don Juan. Juan Carlos later commented that the Duke ‘didn’t get on’ with Franco. Now, in the course of their conversation, Martínez Campos mentioned Don Juan’s annoyance at the way in which Franco, in laying out his plans for the Prince’s education, had ridden roughshod over his own rights as a father to educate his son. The Caudillo was unmoved, reiterating blithely his view that it was one thing to educate a son, another to train a Prince to reign. He added that, if Don Juan didn’t like it, he could do whatever he liked but would lose the chance of ever seeing his son on the throne.60 Once more, it was being made crystal clear that the personal interests of the 15-year-old adolescent mattered little in the wider political game being played out.

When General Juan Vigón, Chief of the General Staff and a fervent monarchist, heard of the choice of Martínez Campos and the arrangements for Juan Carlos, he was shocked, exclaiming, ‘It’s the wrong way to go about this! It’s playing politics rather than educating the boy!’61 Martínez Campos himself was hardly less critical of his own appointment. He remarked to a family friend, ‘This is women’s work.’62 It is fair to say, therefore, that the selection of this rigid and irritable soldier was based not on any consideration of Juan Carlos’s needs but on the fact that he had enjoyed good relations with Franco. It was typical of Martínez Campos’s style that, once in charge, he would prevent Juan Carlos receiving visits from his beloved old tutor, Eugenio Vegas Latapié. In his eyes, the deeply conservative Vegas Latapié was a subversive.63 The consequence of the meeting at Las Cabezas, as far as Juan Carlos was concerned, was that, in early 1955, he would be obliged to leave Estoril once more and start preparing for the entrance examinations for the Zaragoza military academy.

The preparations for this began on 5 January 1955, when Martínez Campos telephoned Major Alfonso Armada Comyn, an intelligent aristocratic artillery officer, son of the Marqués de Santa Cruz de Rivadulla, to arrange a clandestine meeting. As they drove through Madrid, Martínez Campos passed him the letter from Don Juan. ‘Congratulations, General,’ said Armada as he handed it back. With a mixture of contempt and indignation, the general spat out: ‘Are you just pretending to be stupid or are you really thick? Do you think it is possible that I would waste time just so you could congratulate me for something that I don’t like, didn’t ask for and is worrying the hell out of me? Can’t you understand that they’ve dropped me in it?’ A chastened Armada replied in a whisper, ‘Then refuse.’ ‘No,’ replied the general, ‘that wouldn’t be right. It’s an honour, an uncomfortable one, full of responsibilities, especially being dumped on me now that I’m old and I was never any good at bringing up my own children. But let’s not waste time. I don’t have to give you explanations. You’re young and have many children. Both you and your wife know palace life and its secrets.’

Martínez Campos’s choice of Armada was understandable and one that would have profound effects throughout Juan Carlos’s life. The young Major Armada’s credentials, both as a monarchist and as a Francoist, were impeccable. Armada’s father had been a childhood friend of Alfonso XIII, as had his father-in-law, the Marqués de Someruelos. As artillery generals, both were friends of Martínez Campos. At the age of 17, Armada had himself fought as a volunteer on the Nationalist side in the Civil War. In July 1941, shortly after graduating from the artillery academy in Segovia, he had joined the División Azul in order to fight alongside the Germans on the Russian front, for which he was awarded the Iron Cross. After completing his studies at the general staff college, he joined the general staff of the Civil Guard. Now, despite efforts to dissuade the general, Armada was overruled and told to report for duty the next day.64

Martínez Campos instructed Major Armada to prepare lists of officers from the various Army corps who might be recruited as teachers for the young Prince. He was also charged with organizing the staff of the Prince’s residence, choosing suitable companions and arranging Juan Carlos’s studies and even leisure-time reading. Martínez Campos cast aside some of Armada’s suggestions and chose others. A daunting team of officers would supervise the boy’s studies. The Prince’s infantry professor was to be Major Joaquín Valenzuela, the Marqués de Valenzuela de Tahuarda, whose father had been killed in Morocco when he was Franco’s immediate predecessor as head of the Spanish Foreign Legion. The teacher in charge of Juan Carlos’s horse-riding, hunting and sporting development was to be the 50-year-old cavalry major Nicolás Cotoner, Conde de Tendilla, and later to be Marqués de Mondéjar. Brother-in-law to the Conde de Ruiseñada, Cotoner was a grande de España who had fought in the Civil War. He was a firm admirer of Franco which meant that he was viewed with some suspicion in Estoril.65 The chaplain was Father José Manuel Aguilar, a Dominican priest who happened also to be the brother-in-law of Franco’s Minister of Education, the Christian Democrat Joaquín Ruiz Giménez. The history teacher was Ángel López Amo, who had taught Juan Carlos at Las Jarillas. Mathematics was in the hands of a strict naval officer, Lieutenant-Commander Álvaro Fontanals Barón.66

A hint from Martínez Campos had led to the Duque and Duquesa de Montellano graciously putting at the Prince’s disposal their palace in Madrid’s Paseo de la Castellana, where in the 1949–1950 academic year his classmates from Las Jarillas had vainly awaited his return from Estoril. The cost of running the Prince’s establishment was to be met by Carrero Blanco’s Presidencia del Gobierno (the cabinet office). Juan Carlos travelled from Lisbon to Madrid in the company of Martínez Campos on 18 January 1955. This time, there was rather more pomp at his arrival than on his first trip to Spain in November 1948. The Prince travelled by train, in the well-appointed coach in which Franco had made the journey to meet Hitler at Hendaye in October 1940. It is to be supposed that repairs had been effected to the leaks that had blighted Franco’s trip. Juan Carlos was no longer obliged to get off the train on the outskirts of the city. Now, he was met at the Delicias station by the Mayor of the capital, the Conde de Mayalde, by the Captain-General of the region, General Miguel Rodrigo Martínez, and a crowd of several hundred monarchists, most of them aristocrats. His arrival – and unfounded rumours that, at Las Cabezas, Franco had agreed to the return of Alfonso XIII’s mortal remains to Spain – intensified tensions among hardline Falangists. The council of the organization of party veterans, the Vieja Guardia (Old Guard), which attributed to itself responsibility for maintaining the ideological ‘purity’ of the regime, sent a delegation to protest to the Secretary-General of the Movimiento, Raimundo Fernández Cuesta.67

Falangist anger was largely due to the fact that the communiqué issued after the Las Cabezas meeting had immediately sparked off monarchist-inspired rumours that the Caudillo was now actively preparing an early transition to the monarchy. Franco responded quickly to the first mutterings of protest about such a prospect. Within a week of Juan Carlos’s arrival, he gave a widely reproduced interview that dispelled any hopes of his early departure. ‘Although my magistracy is for life,’ he declared pompously, ‘it is to be hoped that there are many years before me, and the immediate interest of the issue is diluted in time.’ Franco was yet again making it clear, to his supporters and to Don Juan, that the monarchy would be a Falangist one in no way resembling that which had fallen in 1931.68 In the face of potential opposition to what seemed to be the appeasement of Don Juan, Franco was asking the docile Falangist hierarchy to postpone the ‘pending revolution’ even longer in return for a Francoist future under a Francoist king.69 Accordingly, in February 1955, he authorized the drafting of laws to block loopholes in the Ley de Sucesión and irrevocably shackle any royal successor to the Movimiento. At the same time, to make this more acceptable to his monarchist supporters, the Falangist edges of the Movimiento would be blurred, censorship of the monarchists would be relaxed, and Eugenio Vegas Latapié was reinstated to the Consejo del Reino.70