Полная версия

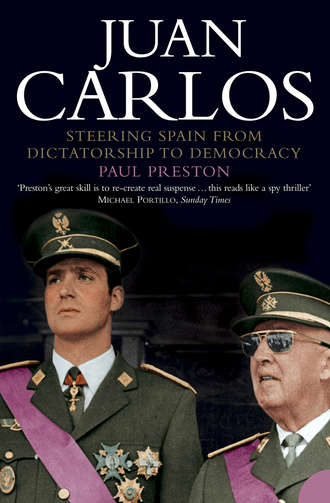

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

On 29 March, Maundy Thursday, the entire family, dressed in black, attended morning mass and took communion at the small church of San Antonio de Estoril near the sea front. The principal Maundy Thursday service, which they also intended to attend, would not take place until the evening. In those days, Catholics still had to prepare for communion by fasting from midnight of the previous day. Rather than fast for 24 hours, the family had taken communion at the early mass. After a frugal lunch, Don Juan and Juan Carlos accompanied Alfonsito to the Estoril golf club where he was taking part in a competition (the Taça Visconde Pereira de Machado). Despite the cold blustery weather, Alfonsito won the semi-final and was looking forward to playing in the final on Easter Saturday. With no sign of a let-up in the cold wind and showers, the Spanish royal family went home. At 6 p.m. they attended the evening mass in the church of San Antonio and then returned home. At 8.30 p.m., the car of the family doctor, Joaquín Abreu Loureiro, screeched to a halt outside the Villa Giralda. Apparently, Juan Carlos and Alfonsito had been in the games room on the first floor of the house, engaged in target practice with a small calibre. 22 revolver, while waiting for dinner. A recent gift, the pistol was, at any reasonable distance, relatively innocuous. Nevertheless, there had been an accident in which Alfonso was shot and died almost immediately.

On Friday 30 March, the Portuguese press carried a laconic official communiqué about Alfonso’s death issued by the Spanish Embassy in Lisbon. ‘Whilst his Highness the Infante Alfonso was cleaning a revolver last evening with his brother, a shot was fired hitting his forehead and killing him in a few minutes. The accident took place at 20.30 hours, after the Infante’s return from the Maundy Thursday religious service, during which he had received holy communion.’ The decision to make this anodyne statement and to impose a blanket of silence over the details was taken personally by Franco.15

Inevitably, however, there were rumours that the gun had been in Juan Carlos’s hands at the time of the fatal shot. Within three weeks, these rumours were being stated as undisputed fact in the Italian press.16 They were not denied by Don Juan at the time nor have they ever been denied by Juan Carlos since. Shortly after tire accident, Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora, a monarchist and member of Opus Dei on Don Juan’s Privy Council who later served Franco as Minister of Public Works, met Pedro Sainz Rodríguez and commented later: ‘His short and portly figure was woebegone because a pistol had gone off in Prince Juan Carlos’s hand and killed his brother Alfonso.’ It is now widely accepted that Juan Carlos’s finger was on the trigger when the fatal shot was fired.17

In her autobiography, Doña María de las Mercedes neither denied nor confirmed that it was Juan Carlos who was holding the gun when it went off. On the other hand, she directly contradicted the official statement. Doña María explained that, on the previous day, the boys had been fooling around with the gun, shooting at streetlamps. Because of this, Don Juan had forbidden them to play with the weapon. While waiting for the evening service, the two boys became bored and went upstairs to play with the gun again. They were getting ready to shoot at a target when the gun went off shortly after 8 p.m.18 One possibility, later suggested by Doña María to her dressmaker, Josefina Carolo, is that Juan Carlos playfully pointed it at Alfonsito and, unaware that the gun was loaded, pulled the trigger. In similar terms, Juan Carlos apparently told a Portuguese friend, Bernardo Arnoso, that he pulled the trigger not knowing that the gun was loaded, and that it went off and the bullet ricocheted off a wall and hit Alfonsito in the face. The most plausible suggestion, possibly made by the boys’ sister Pilar to the Greek author Helena Matheopoulos, is that Alfonsito left the room to get a snack for himself and Juan Carlos. Returning with his hands full, he pushed the door open with his shoulder. The door knocked into his brother’s arm. Juan Carlos involuntarily pulled the trigger just as Alfonsito’s head appeared around the door.19

Doña María de las Mercedes later recalled: ‘I was reading in my drawing room, and Don Juan was in his study, next door. Suddenly, I heard Juanito coming down the stairs telling the girl who worked for us: “No, I must tell them myself”. My heart stood still.’20 Both parents ran upstairs to the games room where they found their son lying in a pool of blood. Don Juan tried to revive him but the boy died in his arms. He placed a Spanish flag over him and, according to Antonio Eraso, a friend of Alfonsito, turned to Juan Carlos and said, ‘Swear to me that you didn’t do it on purpose.’21

Don Alfonso was buried in the cemetery at Cascais at midday on Saturday 31 March 1956. The funeral service was conducted by the Papal Nuncio to Portugal, and was attended by prominent Spanish monarchists and royal figures from several European countries. The desolate Don Juan could barely contain his distress, his eyes full of uncomprehending sorrow. Yet he greeted them all with grace and dignity. The Portuguese government was represented by the President of the Republic. In contrast, the Caudillo was represented merely by the Minister Plenipotentiary of the Spanish Embassy, Ignacio de Muguiro. The Ambassador, Franco’s brother Nicolás, was in bed, recovering from a car accident.22 There were messages of sympathy from all over the world, including one each from General Franco and Doña Carmen Polo.

Juan Carlos attended in the uniform of a Zaragoza officer cadet. His look of vacant desolation masked his inner agony of guilt. After the ceremony, Don Juan took the pistol that had killed Alfonsito and threw it into the sea. There was considerable speculation about the gun’s origins. It has been variously claimed that the weapon had been a present to Alfonsito from Franco or from the Conde de los Andes, or that someone in the Zaragoza military academy had given it to Juan Carlos. The autobiography of Juan Carlos’s mother states discreetly that: The two brothers had brought from Madrid the small six-millimetre pistol and it has never been revealed who gave it to them.’23

Unable to support the presence of his elder son, Don Juan ordered Juan Carlos to return immediately to the Zaragoza academy. General Martínez Campos and Major Emilio García Conde arrived in a Spanish military aircraft in which the Prince was taken back to Zaragoza. The incident affected the Prince dramatically. The rather extrovert figure, so popular with his comrades in the academy for his participation in high jinks and chasing the local girls, now seemed afflicted by a tendency to introspection. Relations with his father were never the same again. Although he would return, superficially at least, to being a fun-loving young man, he was profoundly changed by the event. More alone than ever, he became morose and guarded in his speech and actions.24

The death of her younger son profoundly affected Doña María de las Mercedes who fell into a deep depression, began to drink, and turned ever more for company to her friend Amalín López-Dóriga. Doña María was held partly responsible for the accident by her husband because she had given in to her sons’ repeated requests and allowed them to play with the gun despite their father’s prohibition. According to one such report, by the French journalist Françoise Laot on the basis of interviews with Doña María, she personally unlocked the secreter (writing bureau) where the gun was kept and handed it to Juan Carlos. Françoise Laot would later state that, 30 years after the accident, María de las Mercedes told her, ‘I have never been truly wretched except when my son died.’25 So affected was Doña María that she had to spend some time at a clinic near Frankfurt.

His personal devastation aside, the death of Alfonso significantly weakened the political position of Don Juan. Henceforth, he would be more dependent on the vagaries of the situation of Juan Carlos in Spain. In the words of Rafael Borràs, the distinguished publisher and author of a major biography of Don Juan, the death of Alfonso: ‘deprived the Conde de Barcelona, from the point of view of dynastic legitimacy, of a possible substitute in the event of the Príncipe de Asturias agreeing, against his father’s will, and outside the normal line of succession, to be General Franco’s successor within the terms of the Ley de Sucesión’. Borràs speculates that, had Alfonso lived, his very existence might have conditioned the subsequent behaviour of Juan Carlos in the struggle between his father and Franco.26

The Prince’s uncle, Don Jaime, endeavoured to derive political advantage from the tragedy. His first reaction had been to send a message of sympathy. However, on 17 April 1956 when the Italian newspaper II Settimo Giorno published an account of the accident which pointed the finger at Juan Carlos, he told his secretary Ramón de Alderete: ‘I am distraught to see the tragedy of Estoril dealt with in this way by a journalist who has been used in good faith, because I refuse to doubt the veracity of my unfortunate nephew’s version, as published by my brother. In this situation, and in my position as head of the Borbón family, I can only deeply disagree with the stance of my brother Juan who, in order to prevent future speculation, has neither demanded the opening of an official enquiry into the accident nor called for an autopsy on the body of my nephew, as is normal in such cases.’ These words were reproduced in the French press, presumably via Alderete and with the permission of Don Jaime.

Given that neither Don Juan nor Juan Carlos responded to Don Jaime’s demand, on 16 January 1957, he took the matter further and gave his secretary the following letter:

‘Reuil-Malmaison 16–1–1957.

Dear Ramón,

Several friends have recently confirmed that it was my nephew Juan Carlos who accidentally killed his brother Alfonso. This confirms something of which I have been certain ever since my brother Juan failed to sue those who had spoken publicly of this terrible situation. It obliges me to ask that you request in my name, when you feel that the time is right, that the appropriate national or international courts undertake a judicial enquiry in order to clarify officially the circumstances of the death of my nephew Alfonso (RIP). I demand that this judicial enquiry take place because it is my duty as Head of the House of Borbón, and because I cannot accept that someone who is incapable of accepting his own responsibilities should aspire to the throne of Spain. With a warm embrace.

Jaime de Borbón.’27

There is no evidence to suggest that Alderete acted on the letter or, if he did, that a court showed an interest in the case. Nevertheless, the combination of insensitivity and ambition demonstrated by Don Jaime was breathtaking.

The Madrid authorities were shaken by the news of the accident. Rumours started to circulate in the capital to the effect that Juan Carlos had been so overcome by grief that he was thinking of renouncing his rights to the throne and joining a friary as penance. In fact, as his father had ordered, Juan Carlos was back in Zaragoza within 48 hours of the accident. Franco’s relative silence on this issue was eloquent. Commenting on the tragedy to one of Don Juan’s supporters, he said with a total lack of sympathy ‘people do not like princes who are out of luck’. It was a recurrent theme. Two years later, he explained why he did not favour press references to Alfonsito: )‘The memory could cast shadows over his brother for the accident and make simple folk dwell on the bad luck of the family when people like their Princes to have lucky stars.’28 Perhaps most cruelly of all, within a year of the accident, Franco had permitted the Ministry of Education to sanction the publication and use in secondary schools of a textbook entitled La moral católica (Catholic Morality) which used the incident to explore the limits of personal culpability.29 Years later, Don Juan himself related that, when they met in 1960, Franco had justified keeping him off the throne by saying that the Borbón family was doomed: ‘Just look at yourself, Your Highness: two haemophiliac brothers; another deaf and dumb; one daughter blind; one son shot dead. Such an accumulation of disasters in a single family is not something that could possibly appeal to the Spanish people.’30

Franco’s lack of sympathy was a reflection of his hostility to Don Juan, of his own lack of humanity and perhaps too of the fact that, in March 1956, he was cooling on the idea of a monarchist succession. The scale of Falangist discontent that had been evident since the meeting at Las Cabezas seems to have led to him mulling over the mutual dependence between Caudillo and single party. This was manifested in the cabinet reshuffle of 16 February 1956. The liberal Christian Democrat Minister of Education, Joaquín Ruiz Giménez, was dropped, a punishment for his failure to control unrest in the universities. He was replaced by a conservative Falangist academic, Jesús Rubio García-Mina. Raimundo Fernández Cuesta, the Secretary-General of the Movimiento, was also removed for his failure to control Falangist indiscipline. He had been engaged in preparations to tighten up the Francoist laws lest any future king try to free himself from the ideals of the Movimiento. He was replaced by the sycophantic Falangist zealot, José Luis de Arrese. Alarmingly, for both Don Juan and for those who were looking forward to the eventual creation of a Francoist monarchy, the Caudillo commissioned Arrese to take over the programme of constitutional preparations for the post-Franco future.31

Arrese took his commission to be the preparation of an entirely Falangist future for the regime – one that would have no room for Don Juan nor even for Juan Carlos. The enthusiasm with which he went about his ambitious task would soon provoke a significant polarization of the Francoist coalition. Franco’s cabinet changes were ill-considered reactions to a deep-rooted split at the heart of his coalition. The Ley de Sucesión had been a cunning way of neutralizing regime monarchists and outmanoeuvring Don Juan. However, the prospect of a future monarchy, even a Francoist one, alienated the Falange. And Franco had few options but to cling to the Falange. If the Falange were weakened, the Caudillo’s fate would lie less in his own hands than in those of the senior Army officers who wanted an earlier rather than a later restoration of the monarchy. The situation required a complex balancing act and Arrese was more human cannonball than tightrope walker. The violent protests of Falangist students in February 1956 had been a symptom of a long death agony rather than of youthful vitality. With his mind elsewhere, occupied by the inexorable rise of Moroccan nationalism, and thus underestimating the seriousness of the crisis, Franco had responded instinctively by reasserting Falangist pre-eminence within his coalition. He was not controlling events but letting himself be driven by them.32

Some months earlier, prominent Falangists had presented Franco with a memorandum demanding the swift implementation of their ‘unfinished revolution’. It was effectively a blueprint for a more totalitarian one-party State structure with no place for the monarchy of Don Juan.33 Franco now seemed to be giving the green light for his new Secretary-General to implement the memorandum’s recommendations. Arrese’s plans were seen by Traditionalists, monarchists and Catholics as a totalitarian scheme which would block even limited pluralism under a restored monarchy.34

With the help of Rafael Calvo Serer, the Conde de Ruiseñada, at the time Don Juan’s representative in Spain, elaborated a scheme to block Arrese’s plans by hastening the restoration of the monarchy. Ruiseñada was equally devoted to both Don Juan and to Franco. For some time, he had been in contact with General Juan Bautista Sánchez, the Captain-General of Barcelona, an austere and eminently decent man who was appalled at what he saw as the corruption of the regime. Now, the so-called ‘Operación Ruiseñada’ envisaged a bloodless, negotiated pronunciamiento, rather like that of General Miguel Primo de Rivera in 1923. The lead would be taken by the Barcelona garrison, with the agreement of the other Captains-General, and Franco would be persuaded to withdraw from active politics to the decorative position of ‘regent’. While the restoration of the monarchy was implemented, day-to-day running of the government would be assumed by Bautista Sánchez. The involvement of Bautista Sánchez – the most respected professional in the Armed Forces – helped secure the support of other monarchist generals against Arrese. Don Juan had considerable doubts as to whether this wildly optimistic scheme had any hopes of success but, concerned by Arrese’s plans, agreed to let it go ahead.35

Needless to say, Franco’s intelligence services, which bugged most of Don Juan’s telephone conversations with Spain, were aware of what was being plotted. It was thus all the easier for Arrese, on a tour of the south with the Caudillo, to persuade him that a Falangist future rather than a monarchist one would be truer to his legacy. Franco gave vent to his impatience with Ruiseñada and Don Juan in speeches to which he gave, according to a delighted Arrese, ‘a twist of superfalangism and aggression that seemed to many to be announcing the beginning of the final triumphant era’. In Huelva on 25 April 1956, the Caudillo delighted his audience with an unmistakable and insulting reference to the monarchists and to Juan Carlos. He declared that: ‘We take no notice of the clumsy plotting of several dozen political intriguers nor their kids. Because if they got in the way of the fulfilment of our historic destiny, if anything got in our way, just as we did in our Crusade, we would unleash the flood of blueshirts and red berets which would crush them.’36 At a huge meeting of Falangists in Seville on 1 May, he passionately denounced the enemies of the Falangist revolution. In a passage of his speech that seemed to be directed at Don Juan personally, he referred openly to his own near-monarchical status. Describing the Movimiento with himself at the pinnacle, he said: ‘We are a monarchy without royalty, but a monarchy all the same.’ Stating that national life had to be based on the ideals of the Falange, he declared that: ‘the Falange can live without the monarchy but what could not survive is a monarchy without the Falange.’37 Many Francoists were happy enough to go along with the Movimiento as long as it remained a vague umbrella institution, but defining it so closely to Falangist terms led many to re-evaluate their own preferences.

One of them, the Minister of Justice, the Traditionalist Antonio Iturmendi, was sufficiently alarmed to commission one of his brightest collaborators to produce a critical analysis of Arrese’s preliminary sketches for constitutional change. It was a decision that would have considerable impact on the later trajectory of Juan Carlos. The man given the job was the Catalan monarchist and professor of administrative law, Laureano López Rodó. His report was to be a blueprint of his growing commitment to the cause of Juan Carlos.38 The deeply religious and austere López Rodó, who would quickly rise to a discreet but considerable eminence, was a typical senior member of Opus Dei, quietly confident, hard-working and efficient.

More immediately significant, at the beginning of July 1956, General Antonio Barroso Sánchez-Guerra protested to the Caudillo about Arrese’s activities. He was just about to replace Franco’s cousin Pacón as head of the Caudillo’s military household. Along with two other monarchist generals, one of whom may well have been Bautista Sánchez, he discussed with Franco a version of the Operación Ruiseñada, in which a military directory would take over and hold a plebiscite on the issue of monarchy or republic, in the confident expectation that such a consultation would produce support for the monarchy.39 While hardly likely to go along with Operación Ruiseñada, Franco was sufficiently sensitive to military opinion to begin gradually to restrain Arrese. Nonetheless, when he made a speech to the Consejo Nacional de FET y de las JONS on 17 July 1956, the 20th anniversary of the military uprising, he used notes provided by Arrese, ‘to ensure that he did not say anything, either influenced by other sectors of the Movimiento or in an effort to calm liberal and monarchist anxieties, that might put us in an embarrassing situation later on’.40 Essentially a long hymn of praise to his own achievements, although not without passing praise for Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, the speech reassured Falangists that a future monarchical successor would not be allowed to use his absolute powers to bring about a transition to democracy.41

Unaware that the tide was turning against him, Arrese went ahead with his plans, distributing a draft to members of the Consejo Nacional, the supreme consultative body in the Francoist firmament. Although his text recognized Franco’s absolute powers for life, it left the decision as to his royal successor at the mercy of the Consejo Nacional and the Secretary-General of the Falange. When the text was distributed, there was uproar in the Francoist establishment, and monarchists, Catholics, archbishops and generals joined together in outrage. There were protests from three cardinals, a government minister (the Conde de Vallellano, Minister of Public Works) and several generals, at what seemed to be an attempt to give the Movimiento totalitarian control over Spain and block the return of the monarchy.42 By early January 1957, Arrese had been obliged to dilute his text sufficiently to satisfy his military and clerical opponents.43

Between the two poles of the proposal of Operación Ruiseñada for a negotiated transition to Don Juan and Arrese’s plans for a resurgent Falangism, there emerged a middle option favoured by Luis Carrero Blanco, who had recently been promoted to Admiral. To the detriment of Don Juan and the benefit of Juan Carlos, this would ultimately be adopted by Franco. It consisted of an attempt to build on the Ley de Sucesión by elaborating the legislative framework for an absolute monarchy, in order to guarantee the continuity of Francoism after the death of the Caudillo. The legal expert commissioned to produce a blueprint was Laureano López Rodó. Carrero Blanco had been immensely impressed by López Rodó’s critique of Arrese’s text. Recognizing his talent and capacity for hard work, at the end of 1956 Carrero Blanco asked him to set up a technical secretariat in the Presidencia del Gobierno (the office of the President of the Council of Ministers) to prepare plans for a major administrative reform.44 As Secretary-General of the Presidencia, the doggedly loyal Carrero Blanco was Franco’s political chief of staff. As Franco began to relax his grip on day-to-day politics, Carrero Blanco was gradually metamorphosing into a Prime Minister. López Rodó, in his turn, would swiftly become Carrero’s own chief of staff.

The Opus Dei was thus well placed for the future but was still hedging its bets. Just as Rafael Calvo Serer was banking on Don Juan being Franco’s eventual successor, López Rodó was working on a long-term plan for a gradual evolution towards the monarchy in the person of Prince Juan Carlos. His plans would not come to fruition for many years. For the moment, Bautista Sánchez and other partisans of Don Juan were trying to implement the Operación Ruiseñada in order to marginalize Franco and place Don Juan upon the throne. Bautista Sánchez was under constant surveillance by Franco’s intelligence services, and therefore did not attend, in December 1956, a meeting of military and civilian monarchists involved in the scheme who gathered under the cover of a hunting party at one of the estates of Ruiseñada, El Alamin near Toledo.45 Nevertheless, Bautista Sánchez continued to be seen by the regime as dangerous, particularly when, in mid-January 1957, another transport users’ strike broke out in Barcelona. Although not as violent as that of 1951, the coincidence of anti-regime demonstrations at the university alarmed the authorities.46 Bautista Sánchez was highly critical of the Civil Governor of the province, General Felipe Acedo Colunga, for the brutal force with which demonstrations of workers and students were crushed. Franco perceived this as tantamount to giving moral support to the strikers.47