Полная версия

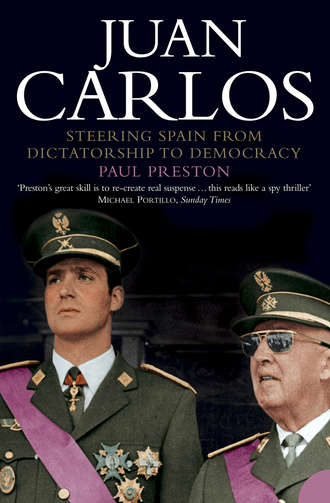

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

Juan Carlos’s classmates at Las Jarillas remember him as a fun-loving child, who worked hard at his academic assignments, was an average student, excelled at sports, and was open and generous.7 As a result, Juan Carlos made solid friendships at his new school. This was underlined by the fact that none of the boys from Las Jarillas would later try to exploit their relationship with the King. It was also shown in the warmth with which they still spoke of Juan Carlos, 50 years later. In 1998, on Juan Carlos’s 60th birthday, a Spanish magazine interviewed the King’s old school friends. Alonso Álvarez de Toledo recalled how, although they were aware of Juan Carlos’s importance at the time (if only because he often received illustrious visitors), they soon accepted him as one of the gang. Jaime Carvajal y Urquijo agreed, describing the young Juan Carlos as ‘an ordinary kid, joyful, naughty, with a heart of gold, a wonderful companion’. Juan Carlos’s cousin, Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias, recalled being surprised at the time by Juan Carlos’s acute intuition and by his already highly developed sense of responsibility. He also recalled how little spare time they had at Las Jarillas, spending, as they did, most of their hours studying or playing sports. According to Carlos de Borbón, Juan Carlos and Jaime Carvajal were the best sportsmen, the latter being the most academically gifted of the group.8

The day at Las Jarillas began with daily mass at which Juan Carlos often served as an altar boy. This was followed by the ritual raising of the Spanish flag. Although classes followed the general Spanish curriculum, there was – as might have been expected of a school whose teachers were all fervent monarchists – a degree of laxity when it came to Francoist political indoctrination. Fernando Falcó y Fernández de Córdoba remembered that, when they sat the exam for what the regime called ‘Formación del Espíritu Nacional’ (Formation of the National Spirit), none of the class knew the Falangist hymn ‘Cara al sol’ by heart. To avoid the scandal that this might provoke in Franco’s Spain, the exam question was magically replaced by another. The children were also given the opportunity to experience some aspects of ordinary life at Las Jarillas. José Luis Leal Maldonado recalled that the Las Jarillas football team always lost to the visiting team of the Las Palomas school. Juan José Macaya recalled a day when the boys discovered a hen house in the grounds of the estate. In spite of – or perhaps in reaction to – the discipline enforced at the school, they proceeded to kill several hens.9

In spite of Juan Carlos’s apparent contentment, certain aspects of his new life in Spain must have been difficult. Outside monarchist circles, his arrival in Spain had been greeted by some with a wave of ill feeling. With the exception of the monarchist daily ABC, the controlled press had marked his arrival with a series of articles featuring malicious and laconic comments about the young Prince, as well as carefully selected, mostly blurry photographs which made him look devious and sly.10 Rumours were spread to the effect that the young Prince was a sadist who watered the plants at Las Jarillas with lime in order to kill them.11 Already at the age of ten, he was obliged to devote many hours to replying to the many cards and letters that arrived for him. He also served an apprenticeship in the boring business of official audiences for the endless streams of monarchists who, after securing the appropriate permission from the Duque de Sotomayor, visited him. Among them was the ineffable General José Millán Astray who arrived accompanied by his permanent escort of Legionnaires. He startled the Prince by shouting, ‘Highness! May the Virgin protect us.’ The tedium was mitigated by the obligatory gifts which ranged from boxes of chocolates to a magnificent electric car.12

A week before the end of his first term, Juan Carlos was visited by the monarchist General Antonio Aranda, a Nationalist hero of the Civil War. Aranda took notes of their conversation: ‘the boy is very likeable, lively and intelligent, I was utterly charmed by him since I thought he would be more sullen and he’s quite the opposite. He asked me about the Army and aeroplanes. This is what excites him and when I explained things to him in detail, he was really pleased. Just then, from the downstairs room where we were talking, we spotted a group of overdressed ladies and gentlemen arriving and the Prince, with total spontaneity and frankness, burst out, “What a drag! They’re coming to interrupt us! Weren’t you really having a good time telling me all this stuff? I know I was enjoying listening to you. Why don’t those people just go away?”’ The Duque de Sotomayor glided in to inform the Prince that he had to receive these new visitors. It was indicative of the ambiguous loyalties of the supposed supporters of Don Juan that Aranda’s notes soon found their way onto Franco’s desk.13

At the end of term, Juan Carlos returned home to Estoril for the Christmas holidays. Towards the end of December, José María Gil Robles took his own children and Juan Carlos to the zoo in Lisbon. With great sensibility, he reflected on the power struggle between Don Juan and Franco, in which the Prince played the role of shuttlecock. Gil Robles was struck by Juan Carlos’s subdued and sombre demeanour: ‘He is still just a child and entirely likeable, but I find him serious beyond his years and even rather sad, as though he were aware of the battle being fought over him. Watching him play in the park yesterday, and later at home, I could not avoid a feeling of sorrow. He is a loveable child. When I think about his future, I feel real compassion for him. What does the future hold for this little boy who, at the age of ten, is the object of such a bitter struggle?’14

In January 1949, Juan Carlos returned to Las Jarillas. However, his sojourn there was dependent on the continuing ceasefire between his father and the dictator. Hostilities were once more imminent. Gil Robles complained bitterly that Franco was failing to fulfil any of the promises made to Don Juan on the Azor. Instructions had been issued that any references to Don Juan had to be to ‘His Highness the Conde de Barcelona’ which appalled the monarchists who referred to him as ‘His Majesty King Juan III’. Juan Carlos was denied the right to use his proper title of Príncipe de Asturias, and was to be referred to only as ‘His Royal Highness Prince Juan Carlos’.15 Throughout 1949, the relationship between Franco and Don Juan deteriorated and Juan Carlos would be the victim. Although Gil Robles and Sainz Rodríguez continually urged Don Juan to recognize that Franco would never make way for the monarchy, he continued to hope, on the basis of the blandishments of Danvila.

The Caudillo made occasional token gestures to ingratiate himself with monarchists, by giving the impression that he was devoted to their cause. Although determined never to cede power to Don Juan, Franco wanted to maintain the credibility bestowed by the link with him. At the end of February, for instance, he attended a mass in El Escorial on the anniversary of the death of Alfonso XIII and was extremely anxious to secure the presence of Juan Carlos at the annual parade to commemorate the Nationalist victory in the Civil War. According to Gil Robles, ‘He is determined that the Prince should watch the parade from a special tribune, lower than his own. The troops in the march-past will be ordered to render him full honours.’ Under intense pressure from Gil Robles, Don Juan informed a disappointed Danvila that his son would not be attending the parade.16 On 18 May 1949, at the opening of the Cortes, as if in retaliation, Franco made a long, rambling, self-congratulatory speech including, en passant, disparaging remarks about Alfonso XIII and his mother Queen María Cristina.17 As a result, Don Juan’s more militant supporters urged Juan Carlos’s immediate return to Estoril.

Oblivious to the gathering storm clouds, Juan Carlos returned to Estoril at the end of May 1949 for summer holidays which would last for nearly 17 months. At the beginning of July, Don Juan wrote to Eugenio Vegas Latapié, inviting him to Portugal and commenting, ‘Juanito is back from Spain full of the joys of spring. He always remembers you with great affection.’ Juan Carlos himself wrote to Vegas Latapié on 17 July, repeating the invitation. After a cruise in the Mediterranean with the entire family, Don Juan left for a hunting party in Scotland on 23 August. Vegas arrived at about the same time and spent nearly a month with Juan Carlos, one day taking him to see a doctor because he had broken a finger. When asked how he broke it, the boy replied ‘thumping my sister Pilar’.18 In opposition to the views of Gil Robles and Sainz Rodríguez, Queen Victoria Eugenia believed that Juan Carlos should return to Las Jarillas after the summer holidays. She was concerned that the boy’s life should not be turned upside down yet again although, in her determination to see her family once more on the throne in Madrid, she also inclined to Danvila’s view that Franco should be placated at all costs. Juan Carlos remained in Estoril while Don Juan dithered.

However, many of his supporters, including the Duque de Alba, Franco’s wartime Ambassador in London, expressed outrage at Franco’s exploitation of his good will. Gil Robles and Sainz Rodríguez worked at persuading Don Juan to drop the duplicitous Danvila and to refuse to allow Juan Carlos to return to Spain. He finally made up his mind after a long conversation with Gil Robles on 26 September 1949. Attempting to put some backbone into his master, Gil Robles baldly pointed out that his collaboration with Franco had severely undermined his credibility. The same man who had been moved by Juan Carlos’s sadness some months earlier now said, ‘Your Majesty must consider that the Prince is the only weapon that he has left against Franco. If you agree in the same terms as last year, you will be disarmed for good.’ Yet again it was obvious that, in Estoril, the needs of a future monarchical restoration would always be of far greater importance than the needs of the child. Don Juan was finally shaken out of his indecision when the plain-speaking Gil Robles made a prophetic warning: ‘Do not think you are indispensable. Within a few years, many will be placing their hopes on the Prince: some in good faith; others out of sheer ambition.’19

At the end of September 1949, Don Juan sent a note, drafted by Gil Robles, informing Franco that, since the agreements made during the Azor meeting had not been fulfilled, the Prince could not remain in Spain.20 Franco responded threateningly in mid-October, with a lengthy note, ‘whose two principal characteristics,’ noted Gil Robles, ‘are overweening arrogance and bad grammar.’ Denying that he had made any promises on the Azor, Franco stated that the benefits of Juan Carlos’s presence in Spain were all on the side of the royal family but also made it clear that he had no plans to replace the dictatorship. His messenger, the servile Danvila, also passed on the Caudillo’s demand that, during his forthcoming State visit to Portugal, Don Juan should pay him a courtesy call at the Palacio de Queluz. Made aware by Gil Robles that this would simply lead to his public humiliation, Don Juan declined. Franco insisted, even going so far as instructing his brother Nicolás to threaten Don Juan that the Cortes would pass a law specifically excluding him from the throne. Don Juan’s snub was the only blot on a spectacular public relations success for Franco. He had arrived in Portugal on the battlecruiser Miguel de Cervantes at the head of a flotilla of 11 warships. The Caudillo’s chagrin may be imagined when he discovered that, as the Spanish fleet left the Tagus estuary, Admiral Moreno, realizing that Don Juan was wistfully watching from the shore, had ordered the ship’s company to form up and render him full honours.21

Don Juan felt troubled that his son would not be returning to Spain. After all, he believed that it was important that Juan Carlos should be educated as a Spaniard in the country over which, one day, he was destined to reign. At the back of his mind was the preoccupation, prompted by the insidious Danvila, that in keeping Juan Carlos in Portugal he might be ruining the family’s chance of a return to the throne. Gil Robles suspected that he was seeking any pretext to send his son back to Las Jarillas. Certainly, he had made no alternative preparations for the resumption of the child’s education in Estoril. In consequence, the 1949–1950 academic year must have been a depressing one for the nearly 12-year-old Juan Carlos. It was good to be back with his family, although Don Juan was often away travelling or hunting. Having coped with separation a year before by becoming closely attached to his classmates at Las Jarillas, he had been torn away from them and now missed them. Kept together as a cohort in the hope that he would eventually rejoin them, they had been moved, for the 1949–1950 academic year, to the ground floor of the palace belonging to the Duque and Duquesa de Montellano in Madrid’s Paseo de la Castellana.

In Portugal, Juan Carlos had to make do with work arranged by the stern Father Zulueta or sent by José Garrido and he rattled around Villa Giralda, missing the friends that he had made in Spain. He was too young to understand why he had been separated from them but not too young to resent it. The disruption to his education and his life again showed how little he mattered within the bigger diplomatic game. It is impossible to calculate how the callous exploitation of his person affected Juan Carlos’s attitude to his father. However, the frequency with which he later spoke of certain individuals being ‘like a second father’ is revealing. Such references would include, bizarrely, Franco, and, much more understandably, José Garrido, and later, the man who would run his household in Spain, Nicolás Cotoner, the Marqués de Mondéjar. Although he always spoke respectfully of Don Juan, perhaps subconsciously Juan Carlos felt that his father had not behaved towards him in the way that a ‘real father’ should.

The boy’s depressing situation at Villa Giralda was exacerbated by anxieties about his godfather and grandfather, Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias, who was gravely ill. Doña María de las Mercedes was desperate to go to Seville to be at the bedside of her dying father. However, in a gratuitously humiliating gesture, Franco denied her permission to enter Spain until the very last moment. When Don Carlos’s situation worsened, she set off anyway but arrived too late. Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias died on 11 November 1949, and Doña María would always hold a grudge against Franco. Years later, she said, ‘I can forgive anything, but Franco, whom I defended in other things to the point of falling out with my friends, I could never forgive for the way he treated my father and for what he did to prevent me arriving in time to see him before he died.’ While at Las Jarillas, Juan Carlos had often spent weekends in Seville with his grandfather. On 14 November, Juan Carlos wrote to one of his friends: ‘I’m sad because of granddad’s death and Mummy is in Seville.’ He was slightly distracted by the arrival of his electric car from Las Jarillas.22

Don Juan continued to waver over his son’s future. Gil Robles advised him not to send Juan Carlos back to Spain, since his presence would be exploited by Franco. Sainz Rodríguez suggested that arrangements for the 1950–1951 academic year could be proposed by the Diputación de la Grandeza (a kind of central committee of the Spanish aristocracy). To make matters worse for Juan Carlos and his father, in December 1949, Don Jaime de Borbón announced that he considered invalid his 1933 renunciation of his rights to the throne on the highly dubious grounds that his physical incapacity had been cured. He attributed this ‘miracle’ to the love of his new German ‘wife’, Carlotte Tiede-mann, a hard-drinking operetta singer. Gil Robles was convinced that Franco was behind this manoeuvre. It was believed that the Caudillo had paid Don Jaime to make his announcement, resolving his immediate debts and providing him with a substantial allowance. Certainly, Franco was looking into ways in which he could make use of Don Jaime’s ambitions.23 His claim to the throne put pressure on Don Juan now, as it would later on Juan Carlos. In the short term, it seemed to determine Don Juan – shortly before disappearing on another hunting jaunt – that his son, who was still without teachers, would continue his education at Estoril, under the alternating supervision of Father Zulueta and José Garrido.24

During a stay in Rome in March 1950, Don Juan was visited by Padre Josémaría Escrivá de Balaguer, the founder of the Opus Dei. Escrivá believed that holiness could be achieved through ordinary work and had created a corps of militant Christians who through austerity, celibacy and devotion to professional excellence lived in a kind of virtual monastery within the real world. At the time, Escrivá was residing in Italy while endeavouring to secure full recognition from the Vatican for the Opus Dei. He was also extremely keen to clinch the support of Franco, for whom he had begun to supervise spiritual retreats at El Pardo in 1944. Now, he reproached Don Juan for keeping his son in Portugal, saying that he was badly advised and ill-informed about the real situation in Spain. He urged him to return the Prince to Spain where he could get a proper patriotic education. Escrivá’s notes of the conversation were dutifully forwarded to Franco. It is probable that at this encounter were sown the seeds of the Opus Dei’s later participation in the education of Juan Carlos.25 Don Juan was looking for a Catholic framework for his son’s development. Initially, he had hoped for the involvement of the Jesuits. Through Danvila, contacts were made with the Spanish province of the Society of Jesus and it was agreed in principle that Jesuits would be chosen as teachers for the Prince. However, when permission was sought from the Vicar General of the Society, the Belgian Father Jean Baptiste Janssens, he issued categoric orders that the proposal was to be rejected. When the request was repeated, he explained that in the experience of the Society of Jesus, the education of royal personages had been ‘pernicious’.26

Finally, in the autumn of 1950, convinced that he had made his point with Franco, Don Juan allowed Juan Carlos to resume his education in Spain. This time, his eldest son was accompanied by his brother, Alfonsito. A new school was set up, not at Las Jarillas, but at the palace of Miramar, the old summer residence of the royal family on the bay of San Sebastián, in the Basque Country. Don Juan seemed to be hoping that distance might diminish the influence of Franco. Again, he made some effort to ensure that his two sons’ academic abilities would be evaluated impartially. The boys at Miramar were thus required to sit, at the end of each academic year, the official exams taken by other children at ordinary schools. Having said that, the ‘normality’ was relative. The examinations were oral and public. When Juan Carlos attended for examination at the Instituto San Isidro in Madrid, his answers had a large crowd breaking into enthusiastic applause. Afterwards, he was seen leaving the examination hall through a great throng of police and clapping well-wishers. The entire process was gushingly reported in the monarchist daily ABC.27

The 16 boys at the school were divided into two groups, one of Juan Carlos’s age and the other of Alfonso’s contemporaries. The older group contained several of Juan Carlos’s pals from Las Jarillas – Jaime de Carvajal y Urquijo, José Luis Leal Maldonado, Alfredo Gómez Torres, Alonso Álvarez de Toledo, and Juan José Macaya. Aurora Gómez Delgado (the French tutor, nurse and housekeeper at Miramar) would later recall that the section of the Miramar palace that housed the school was very beautiful, but also extremely cold. There was no central heating, just one stove on each of the three floors. The permanent teaching staff resided with the boys at Miramar. José Garrido Casanova acted again as headmaster. The stern Father Ignacio de Zulueta taught Latin and religious education, and also organized their weekend outings. Father Zulueta said daily mass at which he would deliver a reactionary sermon. The children would later recall occasions on which Zulueta made them pray for the conversion of the Soviet Union or for the victory of the British Conservative Party in the 1950 elections. In the midst of this particular sermon, Juan Carlos stuck a needle into the bottom of one of his classmates, Carlos Benjumea, whose cry of pain secured him a ferocious dressing-down from the furious priest.

Aurora Gómez Delgado was the only woman on the full-time teaching staff. In addition, a group of non-resident part-time teachers came in a few hours a week to teach specialist subjects such as music, physics and gymnastics. Amongst them was Mrs Mary Watt, who started teaching English to the children in their third year at Miramar.28 One of the reasons for Mrs Watt’s late arrival at Miramar may well have been Juan Carlos’s self-confessed reluctance to learn English – the consequence in part of the education he had received at the hands of Eugenio Vegas Latapié, Julio Danvila, Father Zulueta and other Spanish reactionaries. In a 1978 interview for Welt am Sonntag, he explained that: ‘For patriotic reasons I was predisposed against England and I refused to learn the language. My father used to reprimand me for this, as did my grandmother and my teachers. We had lunch with the Queen of England and my father said to Elizabeth II: “Sit next to him so that he feels ashamed at being unable to answer your questions.” That is precisely what happened. I felt deeply ashamed at only being able to speak in French with the Queen, and realized that patriotism had to manifest itself in other ways and that I had to learn English no matter how much it outraged me to do so.’ Juan Carlos would take a long time to master the English language. By his own admission, the early days of his engagement to Sofia were complicated by the fact that his English was still quite poor and she spoke no Spanish.29

Aurora Gómez Delgado claimed later that Juan Carlos’s worst subject was mathematics – a view confirmed by his maths teacher, Carlos Santamaría. He remained indifferent to the Francoist doctrine imparted in the Formación del Espíritu Nacional, writing to his father on 31 January 1954: ‘Today the text books for political formation have arrived and they are unbelievably boring, both for sixth and fourth year but, since we have to get stuck in whether we like it or not, we’ll just have to study it all with patience.’ Despite his block about English, Aurora was struck by the young Prince’s extraordinary gift for foreign languages. She noted too a clear leaning towards the humanities, in particular towards history and literature. Juan Carlos remained passionate about Juan Ramón Jimenez’s Platero y yo and allegedly showed a highly improbable predilection for Molière and French philosophers such as Descartes and Rousseau. During the holidays, like many boys of his age, he would, more appropriately, read adventure stories by Salgari. Juan Carlos also showed a keen interest in music. He enjoyed classical music, Rachmaninov, Beethoven, Bach as well as Spanish zarzuela, but also contemporary music, Mexican rancheras and the hit songs of the day. He would often be heard walking down the corridors singing popular tunes. Excursions within San Sebastián included trips to the stadium of Real Sociedad, where Juan Carlos was able to indulge his support for Real Madrid when they played in the Basque city. His brother Alfonsito supported Atlético de Madrid. Juan Carlos was most notable at Miramar as a keen and gifted sportsman, who enjoyed horse-riding, tennis, swimming and hockey on rollerskates.30 In 1951, the staff was joined by Ángel López Amo, a young Opus Dei member and professor of the History of Law at the University of Santiago de Compostela. This would be one of the first fruits of Don Juan’s meeting in Rome with Padre Escrivá de Balaguer. It constituted the practical beginning of the strong Opus Dei influence in the life of the Prince.

Although it no longer interrupted his schooling, the tension between Don Juan and Franco did not diminish during Juan Carlos’s stay at Miramar. The Caudillo’s international position was improving through ongoing negotiations with the United States to bring Spain into the Western defensive system. As his confidence grew, Franco’s tendency to behave as if he were King of Spain increased. On 10 April 1950, his beloved daughter Carmen married a minor society playboy from Jaén, Dr Cristóbal Martínez-Bordiu, soon to be the Marqués de Villaverde. The preparations and the accumulation of presents were on a massive scale. The press was ordered to say nothing for fear of provoking unwelcome contrasts with the famine and poverty which afflicted much of the country.31 The wedding itself was on a level of extravagance that would have taxed any European royal family. Guards of honour, military bands, and hundreds of guests including all members of the cabinet, the diplomatic corps and a glittering array of aristocrats, took part in a full-scale State occasion.