Полная версия

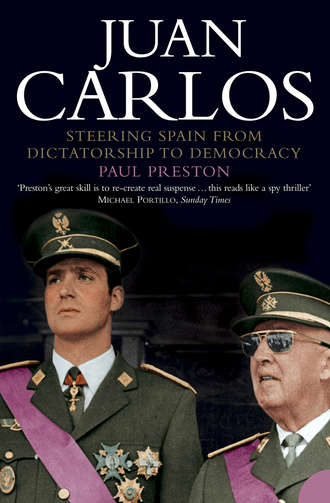

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

The Spanish censorship machinery blocked all attempts from Estoril to have the correct version published. To rub salt into the wound, the Spanish press printed accusations that Don Juan had dishonestly omitted the references that in fact Franco had added. Don Juan was understandably annoyed by Franco’s underhand dealing. However, he wrote him an astute letter, drawing his attention to this apparent interference by third parties anxious to undermine the cordial relations between them. Giving Franco the perfect let-out, he wrote: ‘I imagine that Your Excellency had nothing to do with these changes to what we agreed which, like me, you must have seen for the first time in print.’ However, Franco replied quite brazenly that he had expressly authorized the changes, which he declared to be ‘tiny’ and merely clarifications of what they had agreed at Las Cabezas. Moreover, he reproached Don Juan for publishing the agreed text on the grounds that the communiqué was to be issued only in Madrid. Franco told his cousin Pacón, ‘The note published by the press was brought already drafted by Don Juan. I made some objections. When I reached Madrid and I realized that it lacked a few words about the Movimiento Nacional, I had no hesitation about adding them since Don Juan had not objected when they were mentioned in our conversation. There was no need to consult with him since I knew that he would have to agree.’121

At some level, Don Juan must have known that Franco wanted him to abdicate in favour of his son. Presumably hoping to dispel his own fears, at Las Cabezas, Don Juan had told Franco that he had been asked by Harold Macmillan, the British Prime Minister, if there was any truth in rumours that he was planning to do so. He told Franco that he had vehemently denied having any such intention but had no doubt that the gossip quoted by Macmillan had emanated from Madrid.122 Don Juan had every reason to be concerned. In early April, just a few days after the publication of the communiqué, Carrero Blanco spoke to Benjamin Welles, the correspondent of the New York Times. Carrero dismissed monarchist claims that the Las Cabezas meeting had reasserted Don Juan’s position. ‘Juan Carlos will be King one day. If anything suddenly happens to Franco, he will have to ascend the throne.’ The startled American journalist asked, ‘What about Don Juan? Is he not first in line?’ Carrero Blanco paused interminably before answering dismissively, ‘He is already too old.’123

Juan Carlos returned to Spain in April 1960 to take up residence in the ‘Casita del Infante’, sometimes known locally as the ‘Casita de Arriba’, a small palace on the outskirts of El Escorial, which had been prepared for Franco lest he needed a refuge during the Second World War. It was also known as ‘Casa de los Peces’ (the House of the Fishes), because behind the house there was a pond full of baby carp. Once established there, it was not long before he was received in audience by the Caudillo. It was apparent that Franco’s contempt for Don Juan was matched by a growing affection for the Prince. He continually muttered to Pacón that the Pretender was surrounded by evil influences, such as Sainz Rodríguez, whom he denounced as a leftist and a freemason. ‘Don Juan lives with a coterie of enemies of the regime of whom the most dangerous is Sainz Rodríguez.’ When Pacón innocently asked if Sainz Rodríguez had not once been one of his ministers, Franco replied that he didn’t know him then and had appointed him only at the insistence of Ramón Serrano Suñer. This was a lie, since they had been friends in Oviedo when Franco was stationed there as a Major. On 27 April, he wrote to Don Juan: ‘in the last few days, I had occasion to receive the Prince and talk with him at length. I found him much more grown up than in my last interviews with him and very sensible in his judgements and opinions.’ He invited Juan Carlos to return soon for lunch. The writing on the wall for the Prince’s father was clearer than ever.124

Sir Ivo Mallet, the British Ambassador in Madrid, was in no doubt that Franco had no intention of standing down until he had seen whether Juan Carlos was a suitable successor. It is hardly surprising that, in late May, Don Juan told Benjamin Welles of his anxiety that his son might be ‘persuaded by the atmosphere, by flattery and by propaganda into abandoning his loyalty to his father and accepting the position of Franco’s candidate for the throne’. To prevent this happening, he said, he had appointed as the head of the Prince’s household the Duque de Frías. What is extraordinary is that Don Juan appears not to have discussed his fears with his son.125

Don Juan continued to resist his own dawning perception of the scale of Franco’s deception. In late April, he told Sir Charles Stirling, the British Ambassador in Lisbon, that, at Las Cabezas, Franco had undertaken that there would be no further public attacks on members of his family.126 The Caudillo’s sincerity was revealed in May by a series of lengthy articles printed in Arriba, the principal Falangist newspaper. In laughably naïve terms, they blamed freemasonry for all the ills of Spain over the previous 200 years and managed to insinuate that the British royal family was responsible. Don Juan could hardly miss the implication for himself. The articles were signed by ‘Jakin-Booz’, a variant of Franco’s own pseudonym. At the beginning of the 1950s, writing as ‘Jakim Boor’, the Caudillo had written a series of articles and a book denouncing freemasonry as an evil conspiracy with Communism. On the instructions of the Ministry of Information and Tourism, this new series of articles was republished in full by the entire Spanish press. It was believed that this time the author was Admiral Carrero Blanco. An official of the Ministry told a British diplomat that, as a follow-up to accusations that Don Juan was a freemason, these articles were intended to stress the royal origins of freemasonry and bring the monarchy into disrepute.127

The Spanish edition of Life magazine for 13 June 1960 carried an article on Don Juan in which he was quoted as saying that whatever form the restored monarchy might take, it would not be a dictatorship. Franco had thereupon communicated to Don Juan his displeasure at being called a dictator. Distribution of the magazine had been held up by the censors in Spain and Don Juan had been obliged to write and point out that he had merely stated that he himself would not be a dictator. Besides, he asked, how else could one describe Franco’s form of government? Don Juan believed that Franco eventually agreed to its release only because this was the first thing he had ever asked of him. However, according to the account given to the British Embassy by Benjamin Welles, Franco had said that if Don Juan wanted to commit political suicide, he did not see why he should do anything to stop him by holding up the article.128 In October, Franco showed Don Juan what he really thought. The Marqués de Luca de Tena, owner of ABC, gave a lecture to a monarchist club in Seville in which he extolled the Ley de Sucesión and the Franco regime. However, because he had pointed out that monarchists must accept the hereditary principle, saying: ‘A king is king because he is the son of his father’ and that, ‘if a king comes, the only possible king is Don Juan III,’ a report of the lecture in ABC was banned.129

In the early autumn of 1960, in his capacity as president of Don Juan’s Privy Council, José María Pemán asked Franco to reveal his plans with regard to the succession. The Caudillo replied that he would be succeeded by the ‘traditional monarchy’, whose ‘incumbent’ he told Pemán with a straight face was Don Juan. He described him as ‘a good man, a gentleman and a patriot’. Compounding this farrago of deception, he denied that Don Juan had been eliminated and claimed that the thought of choosing Juan Carlos instead had never crossed his mind. He said that the Prince, ‘because of his age, is an unknown quantity’. In any case, he then went on to reveal that he had no intention of proclaiming the monarchy for a very long time: ‘My health is good and I can still be useful to my Fatherland.’130

CHAPTER FOUR A Life Under Surveillance 1960–1966

In October 1960, Franco received a perceptive report on Juan Carlos from one of his intelligence agents in Portugal. Commenting on the Prince’s presence at the celebration of his parents’ silver wedding anniversary, he wrote: ‘It is certainly the case that Juan Carlos seems more mature by the day, despite the patience and the humility that he has to put on in front of his father. Don Juan treats him harshly, even more so when there is someone present, and is constantly saying “your place is behind me”. It produces discord. The split probably won’t come because there’ll be a marriage and with it a new house, a new life and distance from his father who has got him tightly bound, like the feet of young Chinese girls in iron shoes. At the moment, and we know this from several sources, Juan Carlos is keen to get back to Spain and is fed up with his father and with his grandmother Doña Victoria Eugenia, whose company he finds every day more irksome. Marriage then is a political solution, a device so that the cord doesn’t break altogether.’ Franco must have been delighted to read that: ‘Juan Carlos feels happy only when he is away from Villa Giralda and with his Spanish friends. He has two personalities, one serious, sad and submissive towards his father, and the other when he is out of Don Juan’s sight, among his friends.’1

At the time, it was strongly rumoured that the announcement of his engagement to María Gabriella di Savoia was imminent. The persistence of these rumours provoked frequent denials from Estoril. In early January 1961, as part of this process, Don Juan gave a long interview to Il Giornale d’Italia

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.