Полная версия

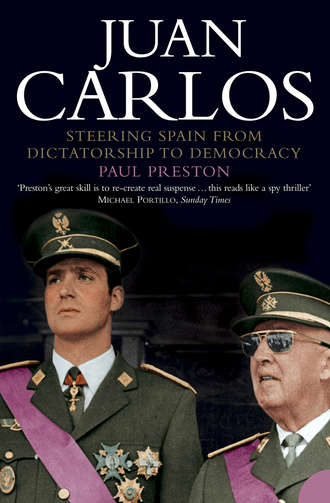

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

Revelling in the weakness revealed by this exchange, Franco twisted the knife further by fostering the claims to the throne of various Carlist pretenders. Accordingly, the ever-busy Pedro Sainz Rodríguez came up with a scheme to strengthen Don Juan’s position. This took the form of an orchestrated ceremony at Villa Giralda on 20 December 1957 involving a delegation of 44 of the most prominent members of the rival dynastic group, the Comunión Tradicionalista. After a solemn mass, Don Juan, wearing the red beret of the Carlists, accepted the principles of the medieval absolute monarchy dear to the Traditionalists. They, for their part, declared that they regarded him as the legitimate heir to the throne. The consequence was that a majority of the Carlists lined up behind Don Juan, although a significant minority of hardliners would continue to push the claims of Don Javier de Borbón Parma and his son Hugo.74

The prize was insufficient to justify the fact that, as the paladin of a liberal monarchy, Don Juan was making two grave errors. Not only was he committing himself to principles inimical to the interplay of political parties, but he was also confirming to Franco the debility of his position. Far from being above partisan interests, he was showing that he had to wheel and deal in order to gain support. When he wrote to inform Franco officially, the Caudillo replied with a patronizing letter of considerable cunning, picking up precisely on this point. He expressed his satisfaction that Don Juan had finally linked up with the only real monarchists (by which he meant those who rejected the liberal constitutional monarchy of his father, Alfonso XIII). He then went on to point out the contradiction of this new position with Don Juan’s previously liberal stance. ‘I refer to the repeated manifestation of your desire to be King of all Spaniards. There can be no argument that the Pretender to the throne of Spain might one day wish to feel that he could be King of all Spaniards. This is normal in monarchical situations in all countries. Everyone who accepts and respects an established order must respect its supreme authorities just as they must treat all citizens with the love given to subjects. But when there are citizens who, from abroad or inside the country, betray or combat their Fatherland, or declare themselves to be agents in the service of foreign powers, such words could well be erroneously interpreted.’ The letter concluded with the condescending advice that Don Juan not make public declarations without first seeking his approval.75

Many of Don Juan’s advisers, like Ruiseñada, believed that a rapprochement with Franco was the only route to the throne. Ruiseñada himself died in mysterious circumstances in France on 23 April 1958. His death in a sleeper compartment of a stationary train in the railway station of Tours, coming a year after the demise of his fellow conspirator Bautista Sánchez gave rise to suspicions of foul play. However, the death was almost certainly the result of natural causes.76 Other monarchists thought that the growing unpopularity of the regime should incline the Pretender to keep his distance. In fact, their hopes were entirely misplaced. Every time that Franco spoke to his cousin Pacón about Don Juan, it was to lament his liberal connections. He muttered that if Don Juan were to accept the postulates of the Movimiento without reservations, there would be no legal impediment. However, it was clear that Franco had no confidence in Don Juan ever doing so. In early June 1958, he said to Pacón: ‘I’m already 65 and it’s only natural that I should prepare my own succession, since something might happen to me. For this, the only possible princes are Don Juan and Don Juan Carlos who are, in that order, the legal heirs. It’s such a pity about Don Juan’s English education, which is of course so liberal.’ He would reveal his lack of trust in Don Juan even more clearly in mid-March 1959 when telling Pacón that Don Juan, ‘is entirely in the hands of the enemies of the regime who want to wipe out the Crusade and the sweeping victory that we won’.77

In May 1958, while the 20-year-old Juan Carlos was still completing his course as a naval cadet, he sailed as a midshipman in the Spanish Navy’s sailing ship, the Juan Sebastián Elcano. It was to cross the Atlantic, putting in at several US ports. At the same time, Don Juan was engaged in a dangerous adventure. In an effort to put behind him the tragedy of Alfonsito, he had decided to sail the Atlantic in his yacht, the Saltillo, following the route of Christopher Columbus. When he reached Funchal in Madeira, he was awaited by Fernando María Castiella, the Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs. Castiella had been sent by Franco to persuade Don Juan to abandon the voyage.78 It is likely that this was motivated less by concerns for Don Juan’s safety than by fears that a successful journey might increase his prestige.

At the time, the Spanish Ambassador to the United States was José María de Areilza, the one-time Falangist who had only very recently become a partisan of Don Juan. As recently as 1955, Areilza had written to Franco protesting at the presence in Spain of Juan Carlos as a ‘Trojan horse’ whose presence delighted ‘all the reds and separatists’.79 Now, newly converted to liberalism, he informed the authorities in Washington of the fact that the Prince was aboard the training ship and alerted the American press. The Embassy was showered with invitations for the Prince in Washington, New York and elsewhere. Serious damage to the storm-battered Saltillo gave Areilza the excuse needed to arrange to have Don Juan picked up by the US coastguard and brought to the Embassy. Once Don Juan was installed there, Areilza was able to incorporate him into the various events arranged for Juan Carlos. The Ambassador requested permission from Franco to receive Don Juan and his son at the Spanish Embassy. However, to the delight of the Americans and the embarrassment of Madrid, Areilza went beyond his instructions and the presence of the two members of the Spanish royal family was converted almost into a State visit. There were much-publicized visits to the Library of Congress, the Pentagon and Arlington Cemetery, to West Point and, in New York, to Cardinal Spellman’s residence, to the Metropolitan Opera, and to the offices of the New York Times.80

While Juan Carlos and Don Juan were in the United States, López Rodó was continuing to beaver away at his plan for the post-Franco monarchy. The first fruit of his work as head of Carrero Blanco’s secretariat of the Presidencia was the Ley de Principios del Movimiento (Declaration of the Fundamental Principles of the Movimiento). The text was presented to the Cortes by Franco himself on 17 May 1958. It was clear that López Rodó had worked on the gradual reform to which he had referred in his conversations with Ruiseñada and Don Juan. The twelve principles were an innocuously vague and high-minded statement of the regime’s Catholicism and commitment to social justice, but within them could be discerned the formal decoupling of the regime from Falangism. The seventh principle stated that: ‘The political form of the Spanish State, within the immutable principles of the Movimiento Nacional and the Ley de Sucesión and the other fundamental laws, is the traditional, Catholic, social and representative monarchy.’81 The biggest obstacle to Don Juan, or his son, ever accepting the idea of a monarchy tied to the regime was the Falange. Now it was shifting slightly. Of the Movimiento Nacional understood as being the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS, central to schemes such as that of Arrese, there was nothing in Franco’s speech.

The text made it appear as if Franco was edging towards the idea of a monarchical restoration, and many monarchists eagerly interpreted the speech in those terms. So soon after Arrese’s aborted plans, this constituted a puzzling u-turn that can be explained largely in terms of López Rodó’s influence. Franco had left the drafting of his speech to Carrero Blanco and he in turn had left it to López Rodó. Either because he had not fully digested its implications, or else because they simply did not bother him, he had not discussed the text in cabinet before making the speech. In the Cortes, several ministers had revealed their dismay at its apparent departure from Falangism by ostentatiously failing to applaud. After a lengthy conversation with Franco in the wake of the speech, Pacón reached the conclusion that none of this mattered, since it was clear that Franco had no intention of leaving power before death or incapacity obliged him to do so. Pacón asked him if he excluded Don Juan as a possible successor in such a case. Franco replied: ‘The designation of a King is the task of the Consejo del Reino but I certainly don’t exclude him. If Don Juan accepts the principles of the Movimiento unreservedly, there is no legal reason to exclude him.’ That Pacón had got it right was revealed on 6 June 1958, when Franco made Agustín Muñoz Grandes Chief of the General Staff replacing Juan Vigón. Muñoz Grandes was to ensure that the Caudillo’s wishes would be carried out if he died or were incapacitated. The appointment made it unequivocally clear that Franco had no intention of handing over to any successor before that time.82

The promulgation of the Ley de Principios del Movimiento had taken place while Juan Carlos and his father were in New York. After their visit was over, Don Juan made the hazardous trip back across the Atlantic in the Saltillo. On reaching the Portuguese port of Cascáis on 24 June, several dozen enthusiastic Spanish monarchists were waiting to congratulate him on his remarkable maritime exploits. On the quayside, Franco’s new Ambassador to Portugal, José Ibáñez Martín, was jostled. When a Portuguese journalist asked the name of the man who had replaced Nicolás Franco in the Lisbon Embassy, several voices replied in unison ‘sinvergüenza’ (scoundrel). As Don Juan posed for photographers, the Ambassador tried to insinuate himself into the frame. Ibáñez Martín was seized and dragged to one side by an ardent young monarchist who had to be restrained from throwing him into the water. When Ibáñez Martín protested to Don Juan, he was ignored. At the reception held afterwards, there was booing when someone announced that a delegation of Procuradores from the Cortes planned to ask Don Juan to accept the Ley de Principios del Movimiento. In his speech, Don Juan declared: ‘I won’t return as Franco’s puppet. I will be King of all Spaniards.’ He told the dissident General Heli Rolando de Telia that only prudence prevented him making a full public break with Franco. Full reports on the various incidents soon reached the Caudillo.83

Even without these declarations, the Caudillo now had yet another reason for resenting Don Juan. Franco always claimed that his real vocation was in the Navy. Only ten years earlier, on 12 October 1948, at the monastery of La Rábida where Christopher Columbus kept vigil on the night before setting out from Palos de Moguer on his historic voyage, Franco had awarded himself the title of Gran Almirante de Castilla (Lord High Admiral of Castile). Considering himself to be the twentieth-century Christopher Columbus, he must have been deeply irritated by the adulation showered on Don Juan for his real maritime achievements.84 Franco was even more displeased when a report from the security services about Don Juan reached him. It consisted of a transcription of a lengthy conversation with a German journalist. Don Juan denounced the illegitimacy of Franco’s tenure of power and stated categorically that the next King had to be committed to national reconciliation.85

It was hardly surprising that the Caudillo’s determination not to hand over the baton for a very long time was reiterated in his end-of-the-year broadcast on New Year’s Eve 1958. Despite the fact that the Spanish economy was on the verge of collapse, with inflation soaring and working-class unrest on the increase, he dedicated the bulk of his lengthy speech (30 pages in its printed version) to a hymn of praise to the Movimiento. In particular, he presented it as the institutionalization of his victory in the Civil War. The underlying message of his obscure ramblings was that the future succession would take place only in accordance with the principles of the Movimiento. Denouncing the failures of the Borbón monarchy in terms of ‘frivolity, lack of foresight, neglect, clumsiness and blindness’, he claimed that anyone who did not recognize the legitimacy of his regime was suffering from ‘personal egoism and mental debility’. After these unmistakable allusions to his person, Don Juan could hardly feel secure about his position in the Caudillo’s plans for the future.86

Franco’s words made it clear that he was keen to dampen the ardour of those monarchists who had taken the Ley de Principios del Movimiento as implying that a handover of power to Don Juan was imminent. Their optimism was exposed at a monarchist gathering in Madrid on 29 January 1959. Progressive supporters of Don Juan held a dinner at the Hotel Menfis to launch an association known as Unión Española. The days of aristocratic courtiers like Danvila or Ruiseñada were now giving way to something altogether more modern. Unión Española was the brainchild of the liberal monarchist lawyer and industrialist, Joaquín Satrústegui. Although Gil Robles was present, he did not make a speech. Those who did – including the Socialist intellectual from the University of Salamanca, Professor Enrique Tierno Galván – made it clear that the monarchy, to survive, could not be installed by a dictator but had to be re-established with the popular support of a majority of Spaniards. The hawk-like Satrústegui directly contradicted Franco’s end-of-year declaration that the Crusade was the fount of the regime’s legitimacy.

To the outrage of the Caudillo, Satrústegui, who had fought on the Nationalist side in 1936, argued that the tragedy of a civil war could not be the basis for the future. He specifically confronted Franco’s oft-repeated demand that Don Juan swear loyalty to the ideals of the uprising of 18 July 1936, saying ‘a civil war is something horrible in which compatriots kill one another … the monarchy cannot rest on such a basis.’ He brushed aside the idea of an ‘installed’ monarchy enshrined in the Ley de Sucesión, declaring openly that ‘Today, the legitimate King of Spain is Don Juan de Borbón y Battenberg. He is so as the son of his father, the grandson of his grandfather and heir to an entire dynasty. These, and no others, are his titles to the throne.’ Franco was livid when he read the texts of the Hotel Menfis after-dinner speeches and fined Satrústegui the not inconsiderable sum of 50,000 pesetas. That the penalties were not more severe, comparable for instance to those meted out to left-wing opponents, derived from the fact that Franco did not want to be seen to be persecuting the followers of Don Juan.87 Given that victory in the Civil War, as he repeatedly stated, was the basis of his own ‘legitimacy’, Franco could not help but be appalled by what had been said and by the fact that Don Juan refused to disown Satrústegui. He told his cousin Pacón that the monarchy of either Don Juan or Juan Carlos, if not based on the principles of the Movimiento, would be the first step to a Communist takeover.88

If the Menfis dinner annoyed Franco, his outrage at a report from his secret service can be imagined. On the day before the Menfis event, Don Juan had received a group of Spanish students in Estoril. If the report written by one of the students was accurate, it presented either a misplaced attempt at humour or the indiscretions of someone who had had too much to drink at lunch. Allegedly, Don Juan had outlined his conviction that, in the event of Franco’s death, all he had to do was head for the Palacio de Oriente in Madrid. Streams of monarchist generals would ensure that he was not challenged. He would abolish the Falange by decree and allow political parties, including the Socialists.89 The report goes some way to explaining the contemptuous manner in which Franco referred to Don Juan in private.

The emergence of Unión Española was merely one symptom of unrest within the Francoist coalition. That Satrústegui could get away with such sweeping criticism of the regime suggested that Franco was losing his grip. Certainly, his inability to deal with the economic crisis other than by relinquishing control to his new team of technocrats suggested that his mind was elsewhere.90To dampen the speculation about his future, Franco permitted Carrero Blanco and López Rodó to continue their work on the elaboration of a constitutional scheme for the post-Franco succession. It would be called the Ley Orgánica del Estado and would outline the powers of the future King. The first draft was given to Franco by Carrero Blanco on 7 March 1959 together with a sycophantic note urging the completion of the ‘constitutional process’: ‘If the King were to inherit the powers which Your Excellency has, we would find it alarming since he will change everything. We must ratify the lifetime character of the magistracy of Your Excellency who is Caudillo which is greater than King because you are founding a monarchy.’ Once the law was drafted, Carrero Blanco proposed calling a referendum. Once this was won – ‘people will vote according to the propaganda that they are fed’ – ‘we could ask Don Juan: do you accept unreservedly? If he says no, problem solved, we turn to the son. If he also says no, we seek a regent.’91

In the wake of the Hotel Menfis affair, Franco was hesitant. He reiterated to Pacón one week later that Don Juan and Prince Juan Carlos must accept that the monarchy could be re-established only within the Movimiento, because a liberal constitutional monarchy ‘would not last a year and would cause chaos in Spain, rendering the Crusade useless. In that way, the way would be open for a Kerensky and shortly thereafter for Communism or chaos in our Fatherland.’92 Unwilling to do anything that might hasten his own departure, he did nothing with the constitutional draft for another eight years.

To increase his freedom of action and to put pressure on Don Juan, Franco continued quietly to cultivate Alfonso de Borbón y Dampierre, the son of Don Juan’s brother Don Jaime. Through the deputy chief of his household, General Fernando Fuertes de Villavicencio, an audience was arranged. Franco liked both Alfonso and his brother Gonzalo and discussed the succession question with them. After asking Alfonso if he was familiar with the Ley de Sucesión, he said, ‘I have made no decision whatsoever regarding who will be called in the future to replace me as Head of State.’ Hearing that Alfonso had been received at El Pardo, José Solís Ruiz, Secretary-General of the Movimiento and other Falangists began to promote the idea of meeting the conditions of the Ley de Sucesión with a príncipe azul (a Falangist prince).93

On 15 September 1958, Juan Carlos would move to the Air Force academy of San Javier in Murcia. He was delighted to be learning to fly and endeared himself to his fellow cadets with his pranks, ably assisted by his pet monkey, Fito, who wore Air Force uniform. Juan Carlos had taught him to salute and shake hands. The relationship with the monkey would see the Prince confined to barracks. Eventually Don Juan obliged him to part company with Fito.94 In the course of the year, the Prince made a number of gestures aimed at consolidating his links with the regime. In the spring of 1959, while still a cadet at the academy, he took part in Franco’s annual victory parade, to celebrate the end of the Civil War. That he was not treated exactly like all the other cadets may be deduced from the fact that, while in Madrid, he stayed at the Ritz where he received many visitors. At some points of the parade, Juan Carlos was applauded. However, at the Plaza de Colón, a group of Falangists and supporters of the Carlist pretender Don Javier, having arrived from the nearby headquarters of the Falange in the Calle Alcalá, began to insult the Prince and shout ‘We don’t want idiot kings.’ The police stood by without interfering. In order to diminish the hostility of the Falange, in late May 1959, Juan Carlos laid a laurel wreath in Alicante on the spot where José Antonio Primo de Rivera had been executed on 20 November 1936. It was to no avail. The Movimiento daily, Pueblo, criticized him for not visiting the historic sites of Francoism with greater frequency.95

On 12 December 1959, Juan Carlos’s military training came to an end and he was given the rank of Lieutenant in all three armed services. At the official ceremony at the Zaragoza military academy, the new Minister for the Army, Lieutenant-General Antonio Barroso, in a speech that he had previously submitted for Franco’s approval, paid a special tribute to Juan Carlos and to Queen Victoria Eugenia. Underlining the importance of the occasion for Juan Carlos’s future, Barroso significantly spoke of how ‘your fidelity, patriotism, sacrifice and hard work will compensate you for other sorrows and troubles’.96 It is not clear whether this was a specific reference to the death of his brother or a more general comment on the situation of a young man separated from his family.

Juan Carlos was now 22 and he had matured during his time in the academies although his tastes were exactly what might have been expected in any young man of his age, particularly an aristocrat – girls, dancing, jazz and sports cars. One of his instructors told Benjamin Welles, a correspondent of the New York Times, ‘He is no older than his actual age.’97 Nevertheless, Franco was happy with the progress made by Juan Carlos but ever more distrustful of his father. He told Pacón in early 1960: ‘Don Juan is beyond redemption and with every passing day he’s more untrustworthy.’ When Pacón tried to explain that the Pretender’s objective was a monarchy that would unite all Spaniards, Franco exploded. ‘Don Juan ought to understand that for things to stay as they were during the Second Republic, there was no need for the bloody Civil War … It’s a pity that Don Juan is so badly advised and is still set on the idea of a liberal monarchy. He is a very pleasant person but politically he goes along with the last person to offer him advice … In the event of Don Juan not being able to govern because of his liberalism or for some other reason, much effort has gone into the education of his son, Prince Juan Carlos, who by dint of his effort and commitment has achieved the three stars of an officer in the three services and now is ready to go to university.’98

It is curious that while in public, Franco seemed to favour the cause of other pretenders, such as Don Jaime and his son, and the Carlists; in private, he had reduced the choice essentially to one between Don Juan and Juan Carlos. Although he harboured no hope of Don Juan accepting the principles of the Movimiento, he had little doubt in the case of Juan Carlos. The other candidates served both as reserves but also as a way of exerting pressure on Don Juan and his son. Franco’s growing fondness for Juan Carlos was leading him to assume that he could rely on Don Juan to abdicate in favour of his son. It was a vain expectation. Don Juan wrote to Franco on 16 October 1959, reporting on an interview with General de Gaulle, in which they had discussed the future of Spain. He wrote: ‘I believe that if one day, this situation were to be addressed using the present legal arrangements, it is to be hoped that a conflict will not be provoked by a rash attempt arbitrarily to alter the natural order of the succession which both the Príncipe de Asturias and myself are determined to uphold.’99 The issue of Juan Carlos’s university education was now about to bedevil even more the relationship between his father and the Caudillo.

Don Juan had originally planned for Juan Carlos to go to the prestigious University of Salamanca. This project apparently enjoyed the approval of Franco. For more than a year, the Prince’s tutor, General Martínez Campos, had been making preparations to this end. He had discussed it with the Minister of Education, Jesús Rubio García-Mina, and the Secretary-General of the Movimiento, José Solís Ruiz. He had also been to Salamanca, for talks with the rector of the university, José Bertrán de Heredia. He had found suitable accommodation and had vetted possible teachers. Then, suddenly, without warning, Don Juan began to have doubts about his Salamanca project in late 1959. On 17 December, General Martínez Campos had travelled to Estoril to make the final arrangements. On the following day, there ensued a tense interview at Villa Giralda. The general began with a report on Juan Carlos’s visit to El Pardo on 15 December. Apparently, after Franco had chatted to the Prince about what awaited him in Salamanca, he had told him that, once he was established at the university, he hoped to see him more often. Don Juan reacted by saying that he was thinking of changing his mind about sending his son to Salamanca. A furious Martínez Campos expostulated that any change in the arrangements at this late stage – after Juan Carlos had received his commissions in the three services – would be infinitely damaging for the prestige of Don Juan and of the monarchist cause. He was appalled that it might now look that he had lied in order to ensure that Juan Carlos received his commissions. He insisted that he would not leave Estoril until the issue was settled one way or the other.