полная версия

полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 5, 1920

What is religion? Wright in the American Journal of Theology, Volume XVI, page 385, quotes Leuba as defining religion as a belief in a psychic superhuman power. Wright has objections to this definition on the ground of its narrowness. He attempts to add breadth to the definition in: "Religion is the endeavor to secure the conservation of socially recognized values, through specific actions that are believed to evoke some agency different from the ordinary ego of the individual or from other merely human beings, and that imply a feeling of dependence upon this agency. Religion is the social attitude toward the non-human environment." This is not synonymous with sectarianism, creeds, dogmas or ceremonies. Creeds and ceremonies have to do with ecclesiasticism not with religion per se. Creeds are developments of theology and dogma is an outgrowth of religion and not religion. Modes of worship developed into rites and ceremonies are ecclesiastical means of fostering the religious spirit but not religion. Religion is not a feeling to be imposed from without. Religion is a life and a life-long process. "The religious life is the response the heart of man makes to God, as the heart of the universe. The religious person is one who is conscious of his divinity because of his kinship with the universe through God, and who because of this consciousness seeks fellowship with God and the Godly."

Having arrived at the conclusion concerning education and religion which are given by some of the most representative students of the subjects, let us ascertain some conceptions of religious education. As indicated in the beginning of this topic, religious education is not regarded as a separate entity. It is a part of the process of efficient education. The human organism is a unit. Life is a whole and connects physical, mental and religious phases. The whole personality is the object for consideration for the educator. The emphasis in education varies from physical to mental and from mental to religious, or social. When the emphasis is placed on the social or religious phase the procedure may be properly called religious education.

Professor Hartshorn carries the social idea to an adequate conclusion. He says: "Religious education is the process by which the individual in response to a controlled environment, achieves a progressive, conscious social299 order based on regard for the worth and destiny of every individual." Professor Peabody states the matter in the following words:300 "Religious education is the drawing out of the religious nature, the clarifying and strengthening of religious ideals, the enriching and rationalizing of the sense of God.... The end of religious education is service...." Dewey's idea of education is much akin to the current conceptions of religious education. "The moral trinity of the school is social intelligence, social power and social interests. Our resources are, (1) the life of the school as a social institution in itself, (2) methods of learning and doing work, and (3) the curriculum."301

The goal of general and religious education is the same; namely, the getting of the individual into the highest and most desirable relationship with both the human and non-human elements, in his environment. The standard of each is found in the functional relationship of each to society. Modes of expression and emphasis may vary but the ideals for both are the same. Dr. Haslett302 has given an unique representation of this conception. "Religious education," says he, "is closely related to secular education and is largely dependent upon it. The fundamental laws and principles of psychology and of education require to be recognized as central." Professor Coe303 reminds us, however, that "religious education is not and cannot be a mere application of any generalities in which the university departments of education deal. It is not a mere particular that gets its meaning or finds its test in the general." Religious education deals with original data and with specific problems that rarely appear in the instruction that is called 'general' and that grow out of the specific nature of our educational purpose. In the analysis of these data and in the determination of the method, we can and must use matter contained in general courses of education. But the field of study of religious education is not exhausted there, but is so specific and yet so broad as properly to constitute a recognized branch of educational practice. The religious purpose in religious education yields the point of view and the principles of classification that are important for religious educators.

The conceptions of religious education just passed in review warrant certain deductions. Any institution which meets adequately the requirements of religious education must have genuinely religious men and women in the entire teaching and official force. Such persons will determine the atmosphere and spirit of the institution. These teachers should have clear conceptions of the ideals of religious education. The blind cannot lead the blind. The students must be trained along three fundamental lines, of the religious life. First, he must have some of the intellectual value of religion. He must have social knowledge. He must have the opportunity of expressing the devotional attitude in worship. He must have the outlet of religious energy in social service. The duty of the college will be far from discharged unless it makes provision for laboratory religion where there is a working place for each member. Religion is a life and the college should be a society where this life may be lived in its fullest extent, encouraging practical altruism and giving the protection which an ideal society affords against demoralization.

Evolution of Religious Education in Negro Colleges and UniversitiesThe problem of religious education in Negro institutions is real. On the basis of the investigation we are able to point out some prominent phases of the problem. The first element of this problem is the teacher. There are in Negro colleges, 22 teachers of religious education who have had no professional training for the work. This means that one-fourth of the entire corp of teachers of religion in these institutions are without the prestige, at least, of even the semblance of professional training. Two main causes account for this. These institutions have not those who are professionally trained on their faculties and they lack funds to procure the service of such persons. In the next place they think it is not necessary.

One observation here is important. These services seem to be significant in proportion to the participation in them by the students themselves. The Sunday School and the Young People's meetings are the most popular services for the students. They do the things in which they have a volitional interest. We cannot thrust our religious experiences upon the students from without. They must achieve their own religious experience in contact with the environment in which they live. The prayer meetings in all except four institutions follow a program which was effective for those who lived in another civilization. The traditional Negro prayer meeting does not function religiously in the life of the Negro college student.

One of the big problems of religious education is compulsion in regard to religious services. Where should that stop? Many are beginning to think that the religious value of the services is often nullified by the compulsory attendance. There are many conscientious objectors among the students who think the removal of compulsion would be conducive to better religious development. But the likelihood of some swinging from one extreme to the other is very great. It is still a problem left for the religious educators in the colleges to solve. The solution must result in the conservation of the good found in the compulsory system and the good to be found in freedom of choice.

Expressional activities are increasing in Negro colleges but with few exceptions these are inadequate in scope and number. It is true that not enough students are able to share in the social service projects. This is really one of, if not the most important factors in religious education. Men gain religious power by acting out their beliefs, allowing their convictions to flow out into service.

There is an unfortunate lack of coordination of religious agencies in Negro colleges. Frequently we find several organizations attempting to do the same thing and each makes a miserable failure in the attempt. More than that, this lack of coordination and correlation results in duplications which surely mean wasted energy and non-effectiveness. If all of the religious agencies were supervised in such a way that each would know his specific task and would not overlap that of other agencies, much more effective work would be the result.

There are signs of hope in the religious education of these Negro colleges. The almost unanimous recognition of the religious motive in efficient education by the educators and the manifest consciousness of needs of better religious education have been mentioned. There are others. An increasing number of trained teachers from Northern, Eastern and Western colleges and universities is evident. These men and women are coming from the institutions where the points of view and training represented in the previous chapter are found. The summer schools of the various colleges and universities in the North, East and West are offering many of these modern religious education courses and larger numbers of the teachers of religious education are availing themselves of the opportunities. Much literature of religious education published recently is finding its way to these schools, the most notable of which is the Religious Education Magazine.

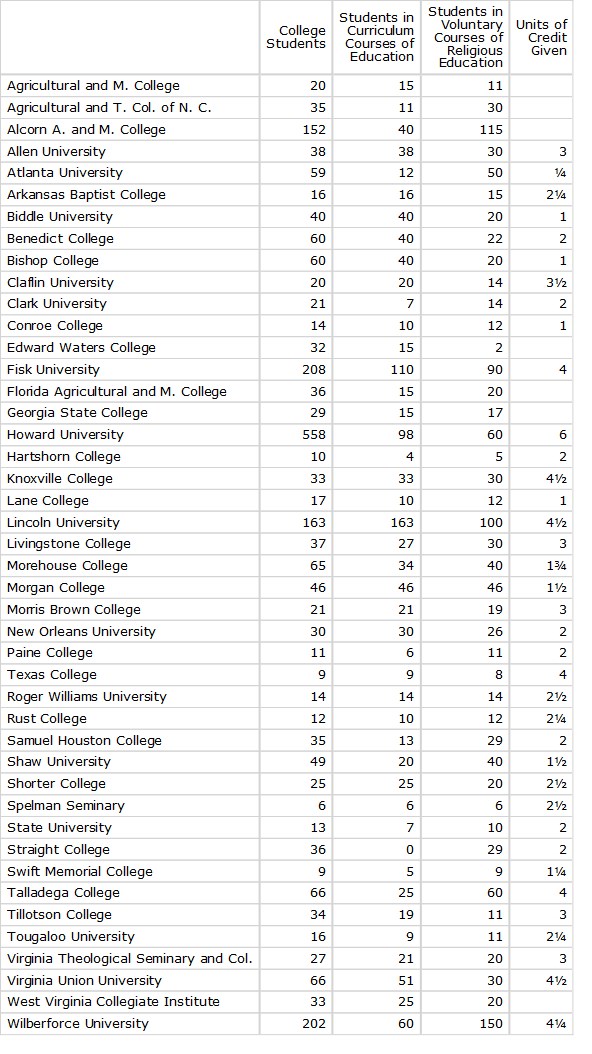

Table Showing Statistics on Religious Education in Negro Colleges

THE AFTERMATH OF NAT TURNER'S INSURRECTION 304

Nat Turner was a man below the ordinary stature, though strong and active. He was of unmixed African lineage, with the true Negro face, every feature of which was strongly marked. He was not a preacher, as was generally believed, though a man of deep religious and spiritual nature, and seemed inspired for the performance of some extraordinary work. He was austere in life and manner, not given to society, but devoted his spare moments to introspection and consecration. He thought often of what he had heard said of him as to the great work he was to perform. He eventually became seized with this idea as a frenzy. To use his own language he saw many visions. "I saw white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle," said he, "and the sun darkened—the thunder rolled in the heavens, and blood flowed in streams and I heard a voice saying, 'Such is your luck, such you are called to see and let it come rough or smooth you must surely bear it,'"305 This happened in 1825. He said he discovered drops of blood on the corn as though it were dew from heaven, that he found on the leaves in the woods hieroglyphic characters and numbers, with the forms of men in different attitudes, portrayed in the blood and representing the figures he had previously seen in the heavens.306 These were without doubt creatures of Nat Turner's own imagination made by him with coloring matter to make the Negroes believe that he was a prophet from God.

Receiving, as he says, further directions from the Holy Spirit, he communicated his designs to four of his most confidential friends. July 4, 1831, the anniversary of American Independence, was the day on which the work of death was to have been begun. Nat Turner hesitated and allowed the time to pass by, when, the mysterious signs reappearing, he determined to begin at once the bloody work. Sunday, August 21, he met those who had pledged their cooperation and support. They were Hark Travis, Henry Porter, Samuel Francis, Nelson Williams, Will Francis and Jack Reese, with Nat Turner making the seventh. They worked out their plans while they ate in the lonely woods of Southampton their feast of consecration, remaining at the feast until long after midnight. The massacre was begun at the house of Joseph Travis, the man to whom Nat Turner then belonged. Armed with a hatchet Turner entered his master's chamber, the door having been broken open with the axe, and aimed the first blow of death. The hatchet glanced harmless from the head of the would-be victim and the first fatal blow was given by Will Francis, the one of the party who had got into the plot without Nat Turner's suggestion. All of his master's household, five in number, soon perished.307

The insurgents procured here four guns, several old muskets with a few rounds of ammunition. At the barn, under the command of Nat Turner the party was drilled and maneuvered. Nat Turner himself assumed the title of General Cargill with a stipend of ten dollars a day. Henry Porter, the paymaster, was to receive five dollars a day, and each private one dollar. Thence they marched from plantation to plantation until by Monday morning the party numbered fifteen with nine mounted. Before nine o'clock the force had increased to forty and the insurgents had covered an extent of territory two or three miles distant from the first point of attack, sweeping everything before them. Nat Turner generally took his station in the rear, with fifteen or twenty of the best armed and reliable men at the front, who generally approached the houses as fast as their horses could run for the double purpose of preventing escapes and striking terror. His force continued to increase until they numbered sixty, all armed with guns, axes, swords, and clubs, and mounted. This line of attack was kept up until late Monday afternoon, when they reached a point, about three miles distant from Jerusalem, the county seat, where Nat Turner reluctantly yielded to a halt while some of his forces went in search of reenforcements. He was eager to push on to the county seat as speedily as possible and capture it. This delay proved the turning point in the enterprise.

Impatient at the delay of his men who had turned aside, Turner started to the mansion house whither they had gone and on their return to the wood found a party of white men who had pursued the bloody path of the insurrectionists and disposed of the guard of eight men whom Turner had left at the roadside. The white men numbered eighteen and were under the command of Captain Alexander P. Peete. They had been directed to reserve their fire until within thirty paces, but one of their number fired on the insurgents when within about one hundred yards. Half of the whites beat a precipitate retreat when Nat Turner ordered his men to fire and rush on them. The few remaining white men stood their ground until Turner approached within fifty yards, when they too followed the example of their comrades, fired and retreated with several wounded. Turner pursued and overtook some of them and their complete slaughter was only prevented by the timely arrival of a party of whites approaching in another direction from Jerusalem.

Being baffled, Nat Turner with a party of twenty men determined to cross the Nottaway river at the Cypress Bridge and attack Jerusalem where he expected to procure additional arms and ammunition from the rear. After trying in vain to collect a sufficient force to proceed to Jerusalem, the insurgents turned back toward his rendezvous and reached Major Thomas Ridley's, where forty assembled. He placed out sentinels and lay down to sleep, but there was to be no sleep that night. An attack on his forces was at hand, and the embarrassment which ensued left him with one half, but Turner, determined to recruit his forces, was proceeding in his effort to rally new adherents when the firing of a gun by Hark was the signal for a fire in ambush and a retreat followed. After this Turner never saw many of his men any more. They had killed fifty-five whites but the tide had turned. Turner concealed himself in the woods but was not dismayed, for by messenger he directed his forces to rally at the point from which on the previous Sunday they had started out on their bloody work; but the discovery of white men riding around the place as though they were looking for some one in hiding convinced him that he had been betrayed. The leader then gave up hope of an immediate renewal of the attack and on Thursday, after supplying himself with provisions from the old plantation, he scratched a hole under a pile of fence rails in a field and concealed himself for nearly six weeks, never leaving his hiding place except for a few minutes in the quiet of night to obtain water.

A reign of terror followed in Virginia.308 Labor was paralyzed, plantations abandoned, women and children were driven from home and crowded into nooks and corners. The sufferings of many of these refugees who spent night after night in the woods were intense. Retaliation began. In a little more than one day 120 Negroes were killed. The newspapers of the times contained from day to day indignant protests against the cruelties perpetrated. One individual boasted that he himself had killed between ten and fifteen Negroes. Volunteer whites rode in all directions visiting plantations. Negroes were tortured to death, burned, maimed and subjected to nameless atrocities. Slaves who were distrusted were pointed out and if they endeavored to escape, they were ruthlessly shot down.309

A few individual instances will show the nature and extent of this vengeance. "A party of horsemen started from Richmond with the intention of killing every colored person they saw in Southampton County. They stopped opposite the cabin of a free colored man who was hoeing in his little field. They called out, 'Is this Southampton County?' He replied, 'Yes Sir, you have just crossed the line, by yonder tree.' They shot him dead and rode on."310 A slaveholder went to the woods accompanied by a faithful slave, who had been the means of saving his master's life during the insurrection. When they reached a retired place in the forest, the man handed his gun to his master, informing him that he could not live a slave any longer, and requested either to free him or shoot him on the spot. The master took the gun, in some trepidation, levelled it at the faithful Negro and shot him through the heart.311

But these outrages were not limited to the Negro population. There occurred other instances which strikingly remind one of scenes before the Civil War and during reconstruction. An Englishman, named Robinson, was engaged in selling books at Petersburg. An alarm being given one night that five hundred blacks were marching against the town, he stood guard with others at the bridge. After the panic had a little subsided he happened to make the remark that the blacks as men were entitled to their freedom and ought to be emancipated. This led to great excitement and the man was warned to leave the town. He took passage in the stage coach, but the vehicle was intercepted. He then fled to a friend's home but the house was broken open and he was dragged forth. The civil authorities informed of the affair refused to interfere. The mob stripped him, gave him a considerable number of lashes and sent him on foot naked under a hot sun to Richmond, whence he with difficulty found passage to New York.312

Believing that Nat Turner's insurrection was a general conspiracy, the people throughout the State were highly excited. The Governor of the commonwealth quickly called into service whatever forces were at his command. The lack of adequate munitions of war being apparent, Commodore Warrington, in command of the Navy Yard in Gosport, was induced to distribute a portion of the public arms under his control. For this purpose the government ordered detachments of the Light Infantry from the seventh and fifty-fourth Regiments and from the fourth Regiment of cavalry and also from the fourth Light Artillery to take the field under Brigadier General Eppes. Two regiments in Brunswick and Greenville were also called into service under General William H. Brodnax and continued in the field until the danger had passed. Further aid was afforded by Commodore Eliott of the United States Navy by order of whom a detachment of sailors from the Natchez was secured and assistance also from Colonel House, the commanding officer at Fortress Monroe, who promptly detached a part of his force to take the field under Lieutenant Colonel Worth.313 The revolt was subdued, however, before these troops could be placed in action and about all they accomplished thereafter was the terrifying of Negroes who had taken no part in the insurrection and the immolation of others who were suspected.

Sixty-one white persons were killed. Not a Negro was slain in any of the encounters led by Turner. Fifty-three Negroes were apprehended and arraigned. Seventeen of the insurrectionists were convicted, and executed, twelve convicted and transported, ten acquitted, seven discharged and four sent on to the Superior Court. Four of those convicted and transported were boys. There were brought to trial only four free Negroes, one of whom was discharged and three held for subsequent trial were finally executed. It is said that they were given decent burial.314

The news of the Southampton insurrection thrilled the whole country, North as well as South. The newspapers teemed with the accounts of it.315 Rumors of similar outbreaks prevailed all over the State of Virginia and throughout the South. There were rumors to the effect that Nat Turner was everywhere at the same time. People returned home before twilight, barricaded themselves in their homes, kept watch during the night, or abandoned their homes for centers where armed force was adequate to their protection. There were many such false reports as the one that two maid servants in Dinwiddie County had murdered an old lady and two children. Negroes throughout the State were suspected, arrested and prosecuted on the least pretext and in some cases murdered without any cause. Almost any Negro having some of the much advertised characteristics of Nat Turner was in danger of being run down and torn to pieces for Nat Turner himself.

There came an unusual rumor from North Carolina. It was said that Negro insurgents there had burnt Wilmington, massacred its inhabitants, and that 2,000 were then marching on Raleigh. This was not true but there was a plot worked out by twenty-four Negroes who had extended their operations into Duplin, Sampson, Wayne, New Hanover, and Lenoir Counties. The plot having been revealed by a free Negro, the militia was called out in time to prevent the carrying out of these well-laid plans. Raleigh and Fayetteville were put under military defence. Many arrests were made, several whipped and released and three of the leaders executed. One of these, a very intelligent Negro preacher named David, was convicted on the testimony of another Negro.316

The excitement in other States was not much less than in Virginia and North Carolina. In South Carolina Governor Hayne issued a proclamation to quiet rumors of similar uprisings. In Macon, Georgia, the entire population rose at midnight, roused from their beds by rumors of an impending onslaught. Slaves were arrested and tied to trees in different parts of the State, while captains of the militia delighted in hacking at them with swords. In Alabama, rumors of a joint conspiracy of Indians and Negroes found ready credence. At New Orleans the excitement was at such a height that a report that 1,200 stands of arms were found in a black man's house, was readily believed.317

But the people were not satisfied with this flow of blood and passions were not subdued with these public wreakings. Nat Turner was still at large. He had eluded their constant vigilance ever since the day of the raid in August. That he was finally captured was more the result of accident than of design. A dog belonging to some of Nat Turner's acquaintances scented some meat in the cave and stole it one night while Turner was out. Shortly after, two Negroes, one the owner of the dog, were hunting with the same animal. The dog barked at Turner who had just gone out to walk. Thinking himself discovered, Turner begged these men to conceal his whereabouts, but they, on finding out who it was, precipitately fled. Concluding from this that they would betray him, Turner left his hiding place, but he was pursued almost incessantly. At one time he was shot at by one Francis near a fodder stack in a field, but happening to fall at the moment of the discharge, the contents of the pistol passed through the crown of his hat. The lines, however, were closing upon Turner. His escape from Francis added new enthusiasm to the pursuit and Turner's resources as fertile as ever contrived a new hiding place in a sort of den in the lap of a fallen tree over which he placed fine brush. He protruded his head as if to reconnoiter about noon, Sunday, October 30, when a Benjamin Phipps, who had that morning for the first time turned out in pursuit, came suddenly upon him. Phipps not knowing him, demanded: "Who are you?" He was answered, "I am Nat Turner." Phipps then ordered him to extend his arms and Turner obeyed, delivering up a sword which was the only weapon he then had.318