полная версия

полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 5, 1920

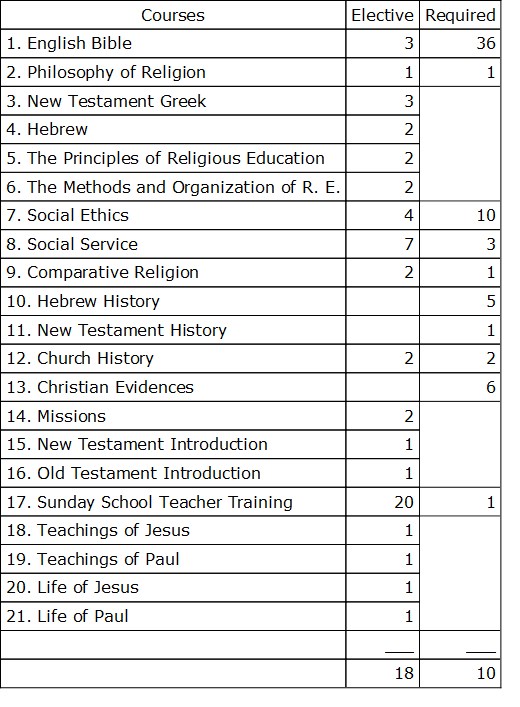

Morehouse College has a combination of the elective and prescribed system relative to the Bible. The English Bible is required in the Freshman year but elective in all of the other years. The following will show the courses in religion which are offered in Negro colleges and will designate the number of institutions offering the several courses as well as whether they are elective or prescribed.

Thus it is seen that the colleges under investigation offer 18 courses for the religious education of those who come under their supervision and prescribe 10 courses for the same purpose.

What is the number enrolled in these curriculum courses? In the 38 private institutions for Negroes of college rank, which come under our observation, there were enrolled for the scholastic year 1916-1917 college students numbering 1,952. The numbers in the several colleges run from 558 to 6. It is interesting to observe that over one-half of that number was registered in four universities as follows: Howard University, 558; Wilberforce University, 202; Fisk University, 208; and Lincoln University, 163. The total is 1,131. Of the remaining 821 Negro college students over fifty per cent of them were distributed as follows among these eight institutions: Talladega College, 66; Virginia Union University, 66; Morehouse College, 65; Benedict College, 60; Bishop College, 60; Atlanta University, 59; Shaw University, 49; and Biddle University, 40. The total is 465. In these twelve colleges and universities we have 1,596 students or over 75 per cent of the total for all of the 38 institutions.

The investigation shows that 1,104 of the 1,952 students are enrolled in these religious education courses. This is more than fifty per cent. In fact, it is 56 per cent of the total number enrolled. Making a comparison of the same institutions which have the majority of students we note a difference in their proportion of students in religious education to the total number enrolled. Howard University has 98; Fisk 110; Lincoln 163; and Wilberforce 60. The total is 331, which is less than a third of the total number enrolled. Talladega has 25; Virginia Union University 51; Shaw University 12; Benedict College 40; Bishop College 40. And the total is 262, which is considerably less than 50 per cent of the remaining 773. But when the twelve schools are taken together they afford 53 per cent of the entire number enrolled in the courses of religious education in the 38 colleges and universities.

The investigation of the amount of credit given for these religious courses reveals facts as interesting as those relative to the number influenced by these courses. We have selected the unit to describe the credit given. By unit we mean a course given 4 or 5 times a week for 36 weeks. This is not intended to be technical. Most of these institutions have 45-minute periods. There are only four exceptions of which three have 60- and one 50-minute periods and a few 55-minute periods. Their periods have been translated in terms of the 45-minute periods for the sake of convenience. The units designate the amount of credit given for both prescribed and elected courses. In the colleges where the elective system is extensive, the units represent the maximum amount of credit which one may receive for courses in religion. For an itemized description of the amount of credit given see chart on last page.

Only one college of the 38 which we had under investigation offered no credit for courses in Bible or correlated subjects. The other 37 offered credit varying from one unit up to six units. Howard University leads in the amount of units offered, and Knoxville College, Virginia Union and Lincoln contend for second place each having four and one-half units. Wilberforce takes third rank with four and one-fourth units. Texas College, one of the smallest in numbers, ties Fisk University for the fourth place. The whole number of institutions investigated offer 85½ units of credit for courses in religious education.

The volunteer courses in colleges have been considered by many exceedingly efficacious for social and religious development. These volunteer courses have various sources. In some few colleges they are offered by the faculty. But in the great majority of cases they come through the channels of the voluntary religious organizations of the respective institutions. The Young Men's Christian Association and the Young Women's Christian Association are the most active sources. The Young People's Societies such as the Christian Endeavor and The Epworth League foster this project in a few of our Negro colleges but very little data can be obtained therefrom, because they keep no accurate records from year to year.

There are thirty-six Young Men's Christian Associations in the colleges comprising this study. All of the co-educational institutions and those for women especially have the Young Women's Christian Association. Therefore, we have thirty-six Young Men's Christian Associations and thirty-six Young Women's Christian Associations in these private colleges and universities. Fourteen institutions report Bible study classes for men under the direction of students, more or less prepared. The membership in these classes is one hundred and seventy. Only five report Bible classes for women.

Mission study classes are also offered under the supervision of the Association in some of the colleges. The men in eleven colleges attend the mission study classes and number three hundred nine. The women have such provisions in two colleges with a membership of eighteen. The numbers in these classes fluctuate from year to year depending largely on two factors, the leaders of the respective association and the leaders of the classes. The personnel of the student body is also a factor. It is among the things natural that from time to time changes in the personnel of the student body bring changes of interest and there is no guarantee of fixity so far as numbers are concerned. It is the ideal of the Central Associations to have the classes sustained each year with an increased efficiency, but all of the institutions testify to the fluctuation caused by the human element in the problem. These courses are mostly mapped out, even to the assigning of specific texts by accepted authors, by the International Association.

To what extent do religious services figure in this work? Worship has always played an important part in the life of human beings. Whether man is in Babylonia worshipping the stars, or in Egypt at the Isis-Osiris shrine, or whether he ascends Mount Olympus with Homer, he is a worshipper. He may ascend to the indescribable, unthinkable realms with Plotinus or he may with twentieth century enlightenment claim allegiance to the God designated Father of all. Yet he worships. It will prove interesting to note the stimulation of this instinct under the supervision of the Negro colleges and universities.

The chapel services claim our attention first because it was unanimously denoted in the questionnaires as one of the services which these institutions emphasize in the life of the students; many of them point out its significance even for the teachers. Every one of these institutions require daily chapel attendance at a service, which lasts on the average one-half hour among the thirty-eight institutions investigated. In nine-tenths of the announcements or bulletins sent from these institutions to prospective students, the chapel attendance is emphasized as one of the rigid requirements of the institutions. In four-fifths of these same institutions, chapel attendance is recorded by some member of the faculty or some one deputized by the authority vested with that right.

What value is the chapel service to the religious development? This cannot be answered indiscriminately. The answer depends upon the chapel activities. One should ask what happens at the chapel service. One student answered that question thus: "The chapel is the place where the president gets us all together to give us all a general 'cussing out' instead of taking us one by one." This expresses the sentiment of several hundred students in those colleges included in our study. During this investigation I visited and had reports from 21 chapel services. Out of the 21 investigated, 19 were exhibits of the opportune reprimand, with the president or his vice-president or the dean performing the task effectively. But it would be a gross injustice even to the twenty-one institutions referred to, if we should leave the impression that the sum total of chapel services is described in the remarks relative to reprimands. A professor of one of the leading Negro colleges, in defending the chapel service, said the "calling down" is merely the introduction and conclusion of the chapel exercises to give opportunity for ex-officio display.

There is obtaining in Negro institutions another condition which perhaps does not suffice as a legitimate excuse for the daily reprimand but at least explains it or is provocative of it. I have in mind the indiscriminate assembling of students from the high school or preparatory department and too often from the grammar school along with the college students. Very often the official censor of morals aims his remarks at some grammar school or high school character of notoriety, but is democratic enough to include "some of you students." There are only two of these colleges of the entire 38 where the high school students are separated from the college students for chapel services. In all cases, except these two, they all assemble in the same auditorium at the same time with the same privileges and under the same circumstances. The most prominent index of distinction between a Junior college student and a Junior High School student in chapel is the locus of the seats.

The chapel exercises are led by the president, chaplain university pastor, or some member of the faculty. Occasionally local and visiting ministers are asked to serve in this capacity. Where the members of the faculty lead they either come in their turn serving every morning, or whenever chapel services take place, until relieved by members of the faculty who likewise serve for a designated period.

The nature of the service varies very slightly in these colleges and universities. One might readily get the impression that they all have the same model. They all begin with religious music selected in most cases by the one who has the music of the institution under supervision. Scripture reading or a brief moral, æsthetic, or ethical address follows. Then prayer usually closing with the Lord's Prayer. In seven of the institutions the scripture reading follows the prayer. A song usually closes the devotional period, but not the chapel exercises. It is subsequent to this song that the moral admonition undisguised usually follows. This is the time when visitors of distinction and otherwise, entertain or detain the students.

The attitude of the students has much to do with the religious value received from the chapel service. All of the authorities have estimated that their particular chapel services have excellent effects upon the students, judging from their attitude at chapel, which they describe as fair. They are confronted, however, with the problem not so easily solved in answering the question. It is extremely difficult for them to distinguish just what part of that attitude comes from the influence of rules and regulations regarding chapel attendance and what part comes from choice.

One of the common religious agencies among Negro colleges is the college church. Twenty-nine of these colleges have church services every Sunday, either morning, afternoon or evening. In twelve institutions they have preaching twice a day. All of them require attendance at church. The nine which have no preaching service at their places every Sunday have it occasionally and make up the deficit by requiring the students to attend a neighboring church, in most cases a church of the denomination under whose auspices the institution is operated. The students attending so far as the requirements of the colleges are concerned are those who live in college dormitories. In no case has this requirement affected students living in the community, beyond campus control. This means that the attendance at the college church aside from that given by those under dormitory supervision is voluntary. A large proportion of the students, therefore, attend other churches, the where and why of which is not known by the investigator. The proportion attending the college churches, however, is ascertained.

The "boarding" students are the church goers so far as the college churches are concerned. The number of college students living in the dormitories of these various institutions is 651 or just a fraction over one-third of the entire number enrolled in the thirty-eight private institutions. The other students, numbering 1,301, go whither they please so far as the institutions are concerned, and no data as to the number attending the college church are available. In these churches the pastors are usually the presidents or some other member of the faculty. In two instances the pastors are called chaplains and have other religious functions during week days. In four cases, the pastors and presidents are identical. This assures the college church which operates on the basis just stated, a good pastor. There are eighteen which have these pastors. Eleven have no pastors or chaplains but invite ministers of the city or neighboring cities to conduct their religious services on Sunday. This service is had at the time which is most convenient for pastors of local churches. The most frequently used hour is from three or three-thirty to four-thirty or five in the afternoon.

The established churches have prayer meeting during the week on one of the following nights: Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday or Saturday. Just why Friday night is boycotted one is unable to say. The "luck" psychology may not have had any part in establishing the tradition along that line. Here again we find the law of the "Medes and Persians" working effectively in securing corporeal attendance. The students are required to be there and are there in a body at least. The times for convening these prayer meetings are chiefly two. Just after supper in nine of the institutions and at the close of the "study" period in twenty-five. Four have the hours between seven and eight o'clock in the evening or thereabouts.

The Sunday School is a prevalent religious agency among the Negro colleges and universities. We find a Sunday School reported in thirty-seven of these. In these Sunday Schools the teachers who reside at the college dormitories constitute a part of the Sunday School faculty. Some of the advanced students are used as teachers and officers.

Another phase of religious service prescribed by several colleges is the Young People's Society. They are all of the same general nature. They take different names such as the Epworth League, The Baptist Young People's Union, the Allen Christian Endeavor and so forth, depending in the main upon their denominational affiliation. Thirty colleges expect their boarding students to be present at these meetings. These thirty institutions have 388 students of college rank living in the dormitories of these respective institutions. Thus three hundred eighty-eight students attend these Sunday afternoon or Sunday evening meetings.

Five colleges which are co-educational have the "quiet" hour for girls on Sunday afternoon. It was designed to be religious or semi-religious at least. Each girl goes to her room and remains there quiet for a designated period of time. During this time she is expected to read her Bible or some religious book, or engage in some meditation which is in keeping with the holy day. Where this idea originated, the writer is unable to say. He, with those who have observed this mystical quiet hour, is puzzled concerning its religious efficacy. One naturally asked those in authority why not a "quiet" hour for the boys as well. There seems to be either a very high compliment paid to the boys or quite an unpardonable insinuation on the inherited tendencies of the girls.

The nature of the Sunday services and the Sunday School is evident without further elaboration. Perhaps a more detailed description of the prayer meeting and the Young People's meeting is in order. A common element is seen in the prayer meetings, "sentence prayers" and singing. Several students think I should add a third, namely, sleeping. Another very frequent activity is the testimony of religious achievements, disappointments and hopes. Eleven colleges have topics which are posted each week prior to the meeting. These topics are religious in the orthodox sense but three of the eleven have pushed far away from the shore of orthodoxy and discuss current topics of vital interest. In these three institutions the meeting re-resembles a forum where every one expresses his opinion, and exhausts his energy on favorite themes. The Young People's meetings without exception, according to reports, have two common phases. The first is the study and discussion of the specified topics, accompanied of course with music and prayers. This might be called the devotional phase of the meeting. Then there is a change in program, in which the literary side is given precedent. Music of a classical nature constitutes the feature of the program.

One of the all important interrogations in this connection is the feeling of the students concerning these religious organizations mentioned. Do they function in the lives of the students? Do they feel that these organizations are vital to them or do they feel as one student in an eastern university? When interviewed he said: "Oh, well, I guess they are pretty good. I suppose they are among the necessary evils of college life."

An extensive interview of the students at seven institutions revealed some interesting facts. The presidents or deans from the thirty-eight colleges gave some data and much opinion on the benefits which the students derived from these organizations, according to the students testimonies and the observation of these presidents or deans. I am not inclined to place too much emphasis upon the students' testimony to the presidents, because, the psychological situation of a student who is asked by a college president what he thinks of the church service, Sunday School and Epworth League is not conducive to frankness. This is especially true of students who know what the president wants him to say. It is a sort of begging the question. The average college student is apt to have too much respect for the president's feelings to be frank in such a case. He likewise has a keen sense of self-preservation. He does not want to incur the displeasure of the president.

In the case of five other institutions, therefore, I had students, Y. M. C. A. workers, interview the leaders of various activities in these colleges with a view to getting their candid opinion and the reflection of the opinion of the other students. In these various ways we secured data which represented a high degree of probability to say the least. Ninety-five per cent of the students in Negro colleges reckon the church service on Sunday a beneficial agency for religious functioning. They vary greatly as to the degree of good derived. In eleven institutions the singing and liturgy are placed first in the rank of importance and the prayer last. These same colleges think the sermon takes second place. By many of this same number congregational singing is given a very high place. The general complaint against the sermon is that it is too dry. I think what is meant by this is that the sermon lacks enthusiasm.

There may be two reasons for the impression of the dryness of the sermon, if the complaint is justified. In the first place, a large number of the college pastors begin their sermons on the assumption that a student's religious life is essentially different from that of the average person in a congregation eight blocks away in another church, a matter which cannot always be taken for granted. That assumption conditions his sermons in character of composition and especially in delivery. The minister works on the assumption that the college man will be interested and benefited by science, philosophy and so forth, regardless of how it is presented. In the reaction against excessive emotion he too often swings to the other extreme.

Again the college students in these universities have come from such a variety of environments. It would be a safe estimate to say that in all Negro colleges 90 per cent of the students are Baptist and Methodists. The registrar's records from these 38 organizations show the following: 983 Baptists; 790 Methodists; and 179 divided among the other denominations. This gives the Baptist and Methodists 90.8 per cent of the total enrollment in these 38 institutions. This means then that 90.8 per cent of these students have had a Baptist-Methodist environment for eighteen or twenty years. Well, what does that matter so far as the estimate of the value of sermons delivered to them? It means that, at least, it is not likely that the impression through childhood, youth, and young manhood or womanhood will be easily offset by the college religious environment in one, two, three or four years. Ideals theoretical, of course, change remarkably, but inevitably some elements of satisfaction afforded by the earlier environment will be demanded in the college environment by the students. Then the Baptist-Methodist environment among the Negroes is, if anything at all, an enthusiastic environment. The sermon is one of the conspicuous features. A student affected by such an environment does not necessarily demand all of the crudities but he does not like the swing to the other extreme.

It is the opinion of students and teachers that the Sunday School is beneficial. From answers received it is calculated that 98 per cent of all the college students believe in the Sunday School's beneficent influence in student life. Several included in their remarks criticism of the literature used. The same beneficent functioning was attested to in behalf of the Young People's meetings, but the hammer falls heavily on the mid-week prayer meeting, out of which very few see any good come. One dubs "the prayer meeting, the driest, deadest event, which takes place just at the time when it is most difficult to be interested in such." Many other similar expressions concerning the prayer meetings were made. It was noted, however, that the schools which had been diverged the fartherest from the traditional prayer meeting had the most good to say in behalf of the prayer meeting. In the great majority of instances the opinion is that the prayer meeting is a bore and should be abandoned. A student in one of the southern colleges, expressing what he had reasons for believing was the student's attitude towards prayer meetings, said: "It isn't interesting and isn't even a good sleeping place because one cannot stretch out as he desires."

The general attitude towards the services on Sunday, however, is favorable. These services are considered beneficial. The students feel that they are moral and religious supports, and in all cases they believe with slight modifications that these services could be more effective. A great premium is placed upon congregational singing and the liturgy in the services.

The week of prayer for colleges has become in these institutions as universal as the national holidays. This occasion affects the regular routine of school work in 22 colleges and universities. It is conducted variously. In some colleges the effort consists of a series of prayer and song services offering opportunity to those who have not made a decision for the better life to do so openly. Their names are recorded, and they become members of the college church, where there is one. Otherwise they are provided for through other means. Those who fail to make decisions are made special objects of moral and religious endeavor during the following months. In the other cases of 18 colleges, a religious survey is made of the student body, usually through the Young Men's Christian Association and the Young Women's Christian Association. This survey is made sometimes prior to the week of prayer and personal workers are selected to do campaign work which is to culminate in decisions during the week of prayer. The week of prayer service is conducted by the president, college pastor, or chaplain usually assisted by the members of the divinity school where there is one connected with the institution. Nine colleges have this convocation led by some strong minister from the community. Four surrender the entire task to a professional evangelist.