полная версия

полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 5, 1920

In 1831 Tennessee forbade free persons of color to immigrate into that State under the penalty of fine for remaining and imprisonment in default of payment. Persons emancipating slaves had to give bond for their removal to some point outside of the State358 and additional penalties were provided for slaves found assembling or engaged in conspiracy. Georgia enacted a measure to the effect that none might give credit to free persons of color without order from their guardian required by law and, if insolvent, they might be bound out. It further provided that neither free Negroes nor slaves might preach or exhort an assembly of more than seven unless licensed by justices on certificate of three ordained ministers. They were also forbidden to carry firearms.359 North Carolina, in which Negroes voted until 1834, enacted in 1831 a special law prohibiting free Negroes from preaching and slaves from keeping house or going at large as free men. To collect fines of free Negroes the law authorized that they might be sold.360 The new constitution of the State in 1835 restricted the right of suffrage to white men. South Carolina passed in 1836 a law prohibiting the teaching of slaves to read and write under penalties, forbidding too the employment of a person of color as salesman in any house, store or shop used for trading. Mississippi had already met most of these requirements in the slave code in the year 1830.361

In Louisiana it was deemed necessary to strengthen the slave code. An act relative to the introduction of slaves provided that slaves should not be introduced except by persons immigrating to reside and citizens who might become owners.362 Previous legislation had already provided severe penalties for persons teaching Negroes to read and write and also had made provision for compelling free colored persons to leave the State.363 In 1832 the State of Alabama enacted a law making it unlawful for any free person of color to settle within that commonwealth. Slaves or free persons of color should not be taught to spell, read or write. It provided penalties for Negroes writing passes and for free blacks associating or trading with slaves. More than five male slaves were declared an unlawful assembly but slaves could attend worship conducted by whites yet neither slaves nor free Negroes were permitted to preach unless before five respectable slaveholders and the Negroes so preaching were to be licensed by some neighboring religious society. It was provided, however, that these sections of the article did not apply to or affect any free person of color who, by the treaty between the United States and Spain, became citizens of the United States.364

So many ills of the Negro followed, therefore, that one is inclined to question the wisdom of the insurgent leader. Whether Nat Turner hastened or postponed the day of the abolition of slavery, however, is a question that admits of little or much discussion in accordance with opinions concerning the law of necessity and free will in national life. Considered in the light of its immediate effect upon its participants, it was a failure, an egregious failure, a wanton crime. Considered in its necessary relation to slavery and as contributory to making it a national issue by the deepening and stirring of the then weak local forces, that finally led to the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment, the insurrection was a moral success and Nat Turner deserves to be ranked with the greatest reformers of his day.

This insurrection may be considered an effort of the Negro to help himself rather than depend on other human agencies for the protection which could come through his own strong arm; for the spirit of Nat Turner never was completely quelled. He struck ruthlessly, mercilessly, it may be said, in cold blood, innocent women and children; but the system of which he was the victim had less mercy in subjecting his race to the horrors of the "middle passages" and the endless crimes against justice, humanity and virtue, then perpetrated throughout America. The brutality of his onslaught was a reflex of slavery, the object lesson which he gave brought the question home to every fireside until public conscience, once callous, became quickened and slavery was doomed.

John W. CromwellDOCUMENTS

The publication of the list of names of Negroes who served in some of the Reconstruction conventions and legislatures elicited a number of comments which furnish desirable information. It is earnestly hoped that any one in a position to supply other missing information will follow the example of our friends whose correspondence we give below.

February 24th, 1920.Mr. Carter G. Woodson,

1216 You St., N.W.,

Washington, D. C.

Sir:

In the Journal of Negro History for Jan., 1920, in giving the names of Negroes who were members of the reconstruction convention to frame a constitution for North Carolina in 1867-68, you omit Cumberland county. Permit me to say that the late Bishop James W. Hood represented that county and played a most prominent part and afterward became Ass't Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State. I was a boy at the time but I remember it. That you may know that I am not an adventurer, I enclose you a sketch of myself which was prepared by request for other purposes and show that I speak somewhat from authority. You will kindly return the same. At the same time you are at liberty to use any part of it that may suit your purpose should you so desire.

With very great respect, I am

Respectfully,(Signed) Geo. C. ScurlockThe sketch of this participant in the Reconstruction follows:

Mr. George C. Scurlock, from the year 1874 was a prominent figure in the Republican party in North Carolina. In the year above stated, when he had barely reached his majority, he was nominated for member of the Board of Education, at a time when all the schools, white and colored, were under the same board. His opponent was one of the most prominent Democrats in the city and a majority of the electorate was white. So popular was Mr. Scurlock that he defeated his Democratic opponent at the polls by a handsome majority and served out his term to the satisfaction of his constituents.

In 1876 he was a delegate to the State Convention that nominated the late Judge Settle for Governor and canvassed the State for him. He was again a delegate to the State Convention in each succeeding four years up to and including the year 1896. In the latter year he headed the delegation. In the campaign of that year, at the request of the State Executive Committee, he canvassed 21 counties in the State for McKinley and Hobart, all of which were carried for the Republican ticket. So pleased was the Committee with the canvass he was making, he was highly commended in letters from the Chairman while still canvassing.

In 1890 he was urged by leading Republicans of his district, including such men as ex-Governor Brogden, to become the Republican candidate for Congress. Long before the convention convened it was evident that he was the strongest man in the field. When the convention met and was organized, ex-Governor Brogden took the platform and in a ringing speech paying a high tribute to the subject of this sketch, placed him in nomination. Before the end of the roll call of counties his nomination was made unanimous. In his canvass for election he had the hearty support of the State organization and many of the leading colored and white Republicans in and without his district and State. In 1892 he was unanimously chosen as a delegate to the Republican National Convention, which met in Minneapolis.

As far back as 1883 he was appointed a clerk in one of the Departments at Washington by Secretary Teller. He held this position until under a Democratic administration he was for partisan reasons asked to resign. President Harrison, recognizing his ability, appointed him Postmaster of his city, Fayetteville.

For more than 20 years he was a leader in the party and so recognized by the late Judge Buxton and such men as the late ex-Congressman O. H. Dockery, and Judges Boyd and Pritchard, now on the bench. Outside his State his ability as an organizer and canvasser was recognized by Hon. J.S. Clarkson and the late William E. Chandler and M.S. Quay.

In a letter of April 8, 1919, Bishop N.H. Heard says:

I was born and raised in Elbert County, Georgia (born a slave), June 25th, 1850. I taught school in '69, 70, '71, and '72. Was a candidate for the Legislature of Georgia in 1872. Attorney General Amos J. Ackerman, of Grant's Cabinet, was in the convention that nominated me, and he canvassed and voted for me. In 1873 I went to Abbeville County, S.C., and taught '73, '74, and '75. Was Deputy U.S. Marshall in 1876 and elected to the South Carolina Legislature.

Mr. M.N. Work has discovered the following:

In the ten years 1876-1886, Negroes were elected to the South Carolina Legislature as Democrats. The Columbia (South Carolina) State in its issue of December 24, 1918, advised that an effort be made to have Negroes enroll in Democratic precinct clubs and participate in the primaries of the State along with white men. As a precedent for this, it was pointed out that: "In 1876 when the Democrats redeemed the State from misrule, they appealed to the Negroes to join their party, and a minority of Negroes, more numerous, perhaps than is generally supposed, wore the 'red shirt.' Many of them did valuable service in behalf of respectable government. During the ten years following that time, until the primary election took the place of the convention system in all but two or three of the counties, the Democratic Negroes were given political recognition. From Barnwell, Colleton, Orangeburg, and Charleston Negro Democrats were elected to the legislature and in a number of counties other Negroes were elected to such offices as coroner and county commissioner.

"With the extension of the primary system a racial line came to be drawn in the Democratic organization and it was made very nearly impossible for a Negro to participate in it. An exception in the party law provided that Negroes who voted for General Hampton in 1876 and who continued to vote the Democratic ticket in succeeding years be allowed to vote in the primaries, but the rules applying to these cases were in a form so rigid that they reduced the Negro Democratic vote."365

Speech of William H. Gray before the Arkansas Constitutional Convention, 1868 366

William H. Gray, a Negro, and delegate to the convention from Phillips County, rose and spoke as follows:

"It appears to me, the gentleman has read the history of his country to little purpose. When the Constitution was framed, in every State but South Carolina free Negroes were allowed to vote. Under British rule this class was free, and he interpreted that 'we the people' in the preamble of the Constitution, meant all the people of every color. The mistake of that period was that these free Negroes were not represented in propria persona in that constitutional convention, but by the Anglo-Saxon. Congress is now correcting that mistake. The right of franchise is due the Negroes bought by the blood of forty thousand of their race shed in three wars. The troubles now on the country are the result of the bad exercise of the elective franchise by unintelligent whites, the 'poor whites' of the South. I could duplicate every Negro who cannot read and write, whose name is on the list of registered voters, with a white man equally ignorant. The gentleman can claim to be a friend of the Negro, but I do not desire to be looked upon in the light of a client. The Government has made a solemn covenant with the Negro to vest him with the right of franchise if he would throw his weight in the balance in favor of the Union and bare his breast to the storm of bullets; and I am convinced that it would not go back on itself. There are thirty-two million whites to four million blacks in the country, and there need be no fear of Negro domination. The State laws do not protect the Negro in his rights, as they forbade their entrance into the State. (Action of loyal convention of '64). I am not willing to trust the rights of my people with the white men, as they have not preserved those of their own race, in neglecting to provide them with the means of education. The Declaration of Independence declared all men born free and equal, and I demand the enforcement of that guarantee made to my forefathers, to every one of each race, who had fought for it. The constitution which this ordinance would reenact it not satisfactory, as it is blurred all over with the word 'white.' Under it one hundred and eleven thousand beings who live in the State have no rights which white men are bound to respect. My people might be ignorant, but I believe, with Jefferson, that ignorance is no measure of a man's rights. Slavery has been abolished, but it left my people in a condition of peonage or caste worse than slavery, which had its humane masters. White people should look to their own ancestry; they should recollect that women were disposed of on the James River, in the early settlement of the country, as wives, at the price of two hundred pounds of tobacco. When we have had eight hundred years as the whites to enlighten ourselves, it will be time enough to pronounce them incapable of civilization and enlightenment. The last election showed that they were intelligent enough to vote in a solid mass with the party that would give them their rights, and that too in face of the influence of the intelligence and wealth of the State, and in face of threats to take the bread from their very mouths. I have no antipathy toward the whites; I would drop the curtain of oblivion on the sod which contains the bones of my oppressed and wronged ancestors for two hundred and fifty years. Give us the franchise, and if we do not exercise it properly, you have the numbers to take it away from us. It would be impossible for the Negro to get justice in a State whereof he was not a full citizen. The prejudice of the entire court would be against him. I do not expect the Negro to take possession of the government; I want the franchise given him as an incentive to work to educate his children. I do not desire to discuss the question of the inferiority of races. Unpleasant truths must then be told; history tells us of your white ancestors who lived on the acorns which dropped from the oaks of Didona, and then worshipped the tree as a God. I call upon all men who would see justice done, to meet this question fairly, and fear not to record their votes."

In the session of January 29th, he said:

"Negroes vote in Ohio and Massachusetts, and in the latter State are elected to high office by rich men. He had found more prejudice against his race among the Yankees; and if they did him a kind act, they did not seem to do it with the generous spirit of Southern men. He could get nearer the latter; he had been raised with them. He was the sorrier on this account that they had refused him the rights which would make him a man, as the former were willing to do. He wanted this a white man's government, and wanted them to do the legislating as they had the intelligence and wealth; but he wanted the power to protect himself against unfriendly legislation. Justice should be like the Egyptian statue, blind and recognizing no color."

Concerning intermarriage between whites and Negroes, Mr. Bradley, a delegate to the convention, having offered to insert in the constitution, a clause "forbidding matrimony between a white person and a person of African descent," on which point nearly all of the members spoke pro and con in that and the following days, Mr. Gray said:

"It was seldom such outrages were committed at the North, where there are no constitutional provisions of the kind proposed. He saw no necessity of inserting any in the present constitution. As for his people, their condition now would not permit any such marriages. If it was proposed to insert a provision of the kind, he would move to amend by making it an offence punishable with death for a white man to cohabit with a Negro woman." At another time he observed on the same subject, that "there was no danger of intermarriage, as the greatest minds had pronounced it abhorrent to nature. The provision would not cover the case, as the laws must subsequently define who is a Negro; and he referred to the law of North Carolina, declaring persons Negroes who have only one-sixteenth of Negro blood. White men had created the difficulty, and it would not be impossible to draw the line which the gentleman desired established."

CORRESPONDENCE

The following letter written primarily to correct certain errors has been productive of much good in bringing to light a number of facts which the public should know:

140 Cottage Street, New Haven, Conn., February 23, 1920.Dr. Carter G. Woodson,

1216 You Street, Washington.

My dear Dr. Woodson:

I find the latest number of your Journal most interesting and permanently valuable, like those that have preceded. I think that the publication is gaining a position in its particular field which promises to make it an accepted authority on historical questions. This makes it the more essential for manifest errors to be carefully guarded against and eliminated from contributed articles.

I observe on page 5 the designation "Tillston College" of The American Missionary Association; the correct name is Tillotson College, for the institution at Austin, Texas. The footnote gives Brawley as authority. I do not have this book at hand but have a suspicion that the erroneous spelling is found there also.

Another statement in the same article which seems to me erroneous in a more serious matter is found at the bottom of page 4, where it is assumed that in 1863 "only 5 per cent of the Negro population was literate." In your book on The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861 you have stated very solid reasons for believing 10 per cent to be about the right estimate. This accords also with the U.S. Census figures of 1870, set forth in a table of which I sent you a copy. Is it not a matter of vital significance to our American history which of these statements is to be accepted? Yesterday I saw posted on the wall of a New Haven church the statement of 5 per cent. It used to be considered allowable to make wild statements on this subject when presenting the claims of Southern education. Indeed I have known the statement to be made in such a connection, that none of the Negroes could read or write before the war. I yield to no one in my estimate of the importance of the work of Northern teachers and Northern schools in the education of the colored people. But their value is not magnified by such exaggerated and reckless over-statement. Rather is it brought under serious question and damaging suspicion.

You have done and are still doing most valuable work in the interest of historical accuracy, and to clear away the fogs of misconstruction and misapprehension concerning the Negro people which have prevailed for at least a hundred years. I could wish that you might see your way as an editor to insist on alteration in a manuscript containing such a misstatement, or at least add an editorial comment on the point.

Wishing for your Journal continued and increasing circulation and popular support, I remain,

Faithfully, yours,G. S. Dickerman.The editor made the following reply:

February 28 1920.Dr. G. S. Dickerman,

140 Cottage Street,

New Haven, Conn.

My dear Dr. Dickerman:

I have your interesting letter in which you make a strong plea for accuracy in the writing of history that the Negro may receive justice at the hands of those represented as treating the records of the race scientifically. You insist that, prior to the emancipation of the race, more than five per cent of the Negro population was literate, and refer to my Education of the Negro Prior to 1861 to support you in that statement. You must observe, however, that I maintain that ten per cent of the adult Negroes had the rudiments of education. It might, therefore, be possible for some one to prove that less than ten per cent of the whole Negro population was at that time able to read and write.

Thanking you for your interest in this work, I am

Yours very truly,C. G. Woodson,Director.The tables to which Dr. Dickerman refers were sent to the editor with a letter, both of which follow:

140 Cottage Street, New Haven, Conn., July 14, 1917.Dr. Carter G. Woodson,

1216 You Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C.

Dear Dr. Woodson:

In preparing a chapter on The History of Negro Education for Dr. Jones, of the Phelps Stokes Foundation, I made a study of the Ninth Census and prepared a table of figures which I suggested for publication in a foot note. But my manuscript was so long that it was thought best to eliminate about a third of it and this table with much besides.

I have therefore thrown this Census study into form for publication in an article by itself. If you like you may have it for Journal of Negro History. Of course the Census is not infallible and the Ninth Census has been especially charged with inaccuracy. But it certainly has some meaning, and I think the confirmation of your conclusions is worth noticing.

If you do not wish to use the article please return it to the above address.

Very truly yours,G. S. Dickerman.The Ninth Census on Negro IlliteracyThe treatise of Dr. Carter Godwin Woodson on The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861 offers an impressive array of evidence to show that there were many more Negroes than have usually been supposed who had some literary knowledge while still under slavery. Other evidence bearing on a subject of so great importance cannot but have interest for historians of that period.

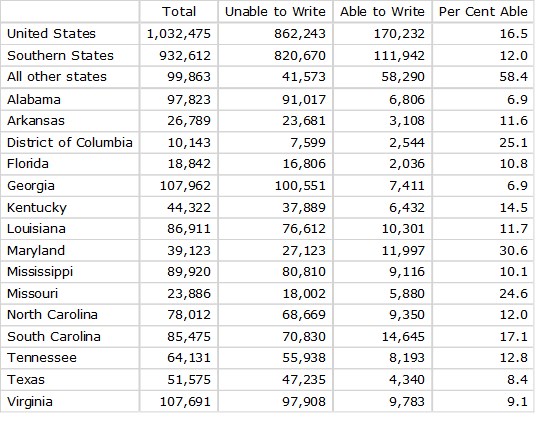

Some of the statistics in the United States Census of 1870 are in point: Figures are there given for the colored men of voting age, that is for those over 21, who were unable to read and write. There are also given the total numbers of colored men of voting age in the several States. Subtracting the former from the latter will then give the number of those able to read and write. The results appear in the table presented below:

Colored Males 21 Years of Age and Upward in 1870; with Reference to their Ability to Write

This Census gives the figures for women of color over 21 years of age who were unable to write; but not the whole number of women of color over 21. If however we assume the proportion of all Negro males to all Negro females to hold the same for those over 21 we arrive at the conclusion that the whole number of women of color over 21 was 1,072,847 for the United States; of whom 946,332 were unable to write and 126,515 were able. That is, in 1870, there were approximately 126,515 women of color of 21 years of age and upward who were able to read and write. This number added to the 170,232, found for the number of literate men, gives a total of 296,747 Negroes of 21 years of age and upward who were able to read and write; which is 14 per cent of the whole number. There must have been a considerable increase between 1863 and 1870, but one can hardly suppose it to have been over 4 per cent, or 84,212, which substantiates the estimate of about 10 per cent of the Negroes as able to read and write at the date of emancipation. We may suppose that the number of those who were able to read, but did not add to this the accomplishment of writing, must have been much larger.

The existence of so large a body of Negroes who already had the rudiments of an education goes far to account for the rapid growth of schools as soon as the Negroes were made free, and especially for that eagerness that was shown for advanced learning which made an almost immediate demand for secondary schools and colleges at the more important centers of population throughout the South. The people had received, in some way or other, a love of education and a start in obtaining it under the old slave system, so that when the new chance came they were ready to make a good use of it.

G. S. Dickerman.BOOK REVIEWS

The Centennial History of Illinois, Volume III. The Era of the Civil War 1848-1870. By Arthur Charles Cole. The Illinois Centennial Commission, Springfield, Illinois, 1919.