Полная версия

The New English Table: 200 Recipes from the Queen of Thrifty, Inventive Cooking

Spiced Barley with Leeks, Root Vegetables, Oregano, Nutmeg, Allspice and Butter

Another useful way to eat barley. For 2 people, sweat (gently fry) 1 thinly sliced young leek in butter until soft, then add 150g/5½oz pot barley with a large pinch each of dried oregano, ground nutmeg and ground allspice. Cook for a minute, then add dried root vegetables such as Jerusalem artichokes, beetroot, turnips or squash. Cover with water and simmer for 20 minutes, until the barley is tender. Eat with roast meats – poultry, game birds and lamb – or try with a little fresh soft goat’s cheese, briskly mixed with the barley just as you sit down to eat. A little leafy salad beside …

Barley in Breadcrumbs

Leftovers of the above barley recipe and the recipe on can be rolled into small balls, dipped in seasoned flour, then beaten egg, followed by breadcrumbs, then fried and eaten as a little appetiser.

BEANS

Bean Sprout and Herb Soup

Baked Beans with Bacon, Molasses and Tomato

Pinto Beans and Venison

White Bean Broth with Buttered Tomato and Lettuce

Bean and Herb Salads

Quick Braised Butterbeans

Rifling through the bags of beans in the kitchen drawer, it’s easy to imagine how a geologist feels about his collection of favourite pebbles. Beans make funky percussion noises as they fall around in the bags, a hollow sound reminding us that here is a dry store, a useful source of food. And they are so pretty. Spotty like bird’s eggs, black, purple, white, red and green – it’s a glamorous palette for a humble, economic food. But what a food. My week never passes without a foray into the drawer for one type or another and, depending on whether I use dried beans or canned cooked ones, a pan will soon be simmering with something good under the lid. White beans, garlic and tomatoes are a classic combination; meaty-flavoured brown beans taste good with a hint of sweet-sourness and the richness of added pork; Mexican black beans are a favourite, because they are not too floury; green flageolet beans with shallots and butter is a dish I will keep going back to all my life. More recently, I have discovered that mung bean sprouts are lovely in herby soups.

However, with names like flageolet, haricot and cannellini, we are not talking of one British pulse. All beans sold dried or cooked and canned are imported. But they belong in our kitchens on various counts. One is that we do not grow them – we could, and should, develop some varieties, however – and the other is that we, the British, not famous for eating any beans other than Heinz, would discover that they make a valuable addition to our diet. Beans, along with lentils, grains and peas, need to become a central quotidian food. This is why:

Buying into beans is a humanitarian deed. They are the ultimate low-impact food, being as good for the places where they grow as they are for human nourishment. Their virtues are remarkable: they need little water compared to other food crops, tending to grow well in dry climates (major producers are Africa, India, Pakistan, Turkey and the Middle East); there are hundreds of varieties, so they are a diverse, anti-monoculture food crop whose cultivation benefits soil fertility and increases protection against disease and pests; bean plants also fix nitrogen in the soil, and so are intrinsic to traditional crop rotation as a ‘green manure’ – they also grow well without chemicals in an organic system and tend to be grown with the assistance of pesticides only when the farmer can afford it. A pulse grown in a developing country is usually free of spray. When last tested by the UK’s pesticides residue committee, only 11 out of 81 samples tested positive for residues. These results are quite favourable for the consumer, but it is easy to buy pulses from an organically certified source.

On the downside, beans are still largely a commodity crop and there are very few fairly traded beans on the British market, although Suma, an organic supplier, sells fairly traded aduki and black beans.

On a more selfish note, we should eat more beans because they are so good for us. They are a low-cost way of eating a high-protein food containing plenty of healthy complex carbohydrates. They are packed with vitamins, iron and calcium. It is important to note, however, that while fresh beans are very high in vitamin C, dried beans contain virtually none. The good news is that canned beans, which tend to be cooked using fresh pulses, retain about 50 per cent of their vitamin C. I was delighted to discover this, as I have always felt guilty about buying canned beans, believing I should virtuously go through the whole cooking process. The truth is I rarely have the time, although it must be said that there is a much wider range of dried beans available, including some rare ones like appaloosa beans from America and black turtle beans from China.

Buying beans

I buy from Infinity Foods, a workers’ co-operative in Brighton that sells a vast range of high-quality pulses. (See www.infinityfoods.co.uk; tel: 01273 424060). Monika Linton imports great beans for her London-based business, Brindisa, both dried and bottled, rather than canned (www.brindisa.com; tel: 020 8772 1600).

Basics when preparing dried beans

Unlike lentils, beans need to be soaked before cooking or they will split. If you soak them in cold water for several hours or overnight, then boil them for the correct amount of time, they should stay intact and slip lightly around the pan, mixing well with the other ingredients. It would be good to have a chart of cooking times for beans but no such thing can exist. The cooking time depends on size and type and also, more crucially, on how recently the beans were picked and dried – the older a bean is, the longer it takes to cook. It must be said that most beans sold in the UK are fairly aged, so expect to leave them for a good 1½–2 hour simmer. Test after about 50 minutes, though, just in case they are done. Overdone beans are floury and disgusting.

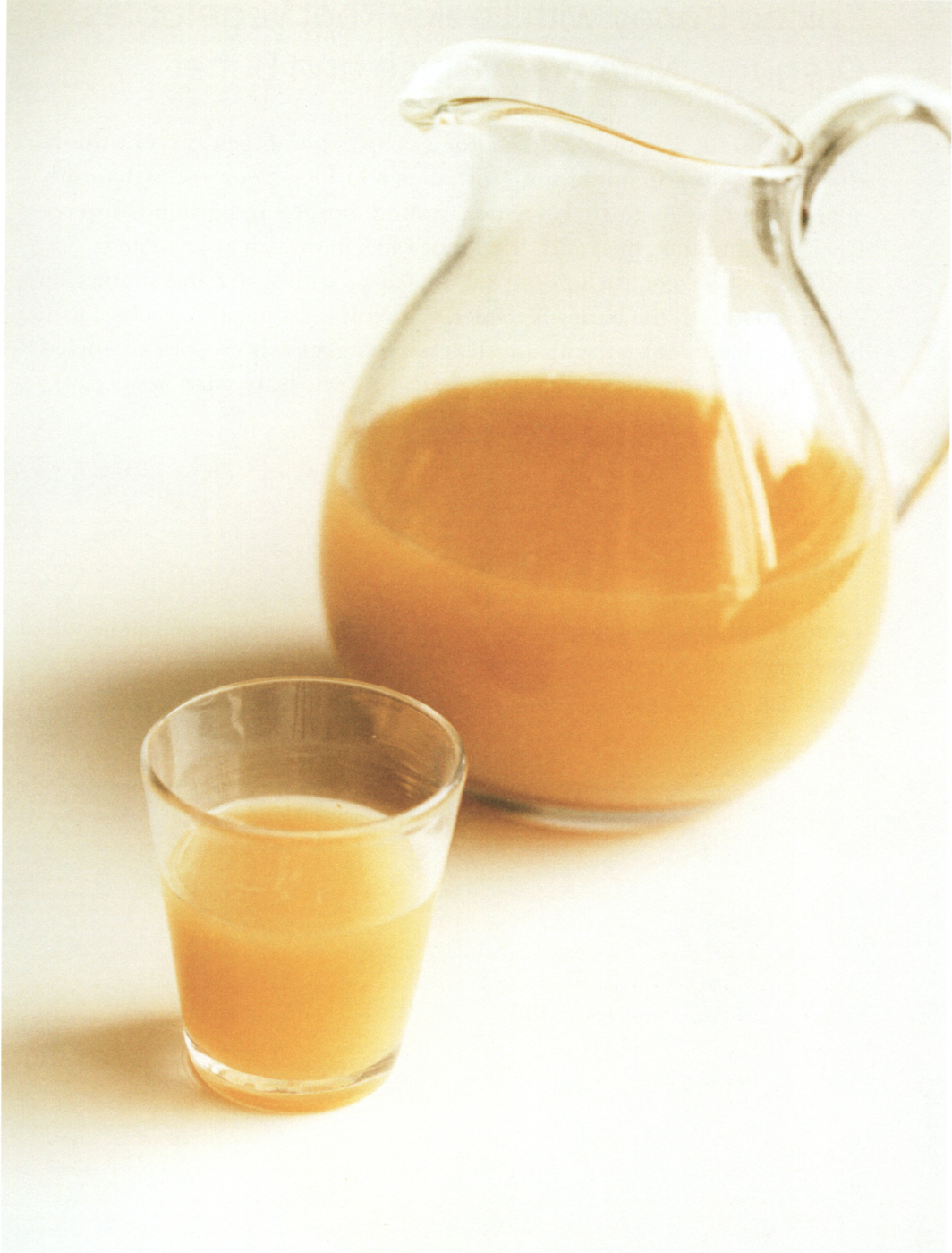

Bean Sprout and Herb Soup

A light soup, finished with a herb sauce. With a supply of fresh chicken stock, brewed from the bones after the roast (see here), this broth can be made in about 5 minutes. I have used mung bean sprouts, which are popular in Southeast Asian cooking. It is easy to buy fresh ones, but I have a three-tier clear plastic seed ‘sprouter’, known to the family as the ‘farm’, in which the beans grow to a useable sprout within a week or so. Mung beans have very little flavour when raw but take on a delicate, fresh, beany taste as soon as they land in the pan.

Serves 2

2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

2 spring onions, chopped

1 garlic clove, chopped

2 handfuls of mung bean sprouts and seed sprouts (any kind)

225g/8oz canned or cooked lentils, drained of any liquid

600ml/1 pint chicken stock

sea salt

For the sauce:

leaves from 3 sprigs of parsley, finely chopped

1 teaspoon chopped chives

4 basil leaves, torn

2 tablespoons freshly grated Parmesan cheese (or other mature cheese, such as Twineham Grange or pecorino)

1 tablespoon pine nuts, toasted in a dry frying pan until golden

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

Heat the oil in a pan, add the spring onions and garlic and cook for about 2 minutes, until soft and translucent but not browned. Add the sprouts, lentils and stock and bring to the boil. Simmer for 1 minute and then remove from the heat. Taste and add salt if necessary.

Mix the sauce ingredients together, breaking up the pine nuts as much as possible with the back of a wooden spoon. Spoon the sauce over the soup once it is ladled into bowls.

Baked Beans with Bacon, Molasses and Tomato

The nation’s favourite canned meal was once a pottage, which was exported to the Americas by early settlers and became Boston baked beans – a dish of salt pork and haricot beans sweetened with molasses (but not tomatoes, which I have added here to keep up with modern tradition). An earthenware pot or cast-iron casserole with a well-fitting lid prevents the beans and sauce drying out during cooking. Try to find good bacon – dry-cured from naturally reared pork will let a gentle meaty flavour seep into the beans.

Serves 4

175g/6oz white haricot or navy beans

4 tablespoons cold-pressed sunflower oil (or extra virgin olive oil)

2 thick slices of green (unsmoked) back bacon

1 onion, finely chopped or grated

1 garlic clove, finely chopped

200ml/7fl oz passata (puréed tomatoes)

1 dessertspoon molasses

1 tablespoon English mustard

1 tablespoon Worcestershire sauce

sea salt

Soak the beans in plenty of water overnight or for 24 hours, then drain.

Preheat the oven to 150°C/300°F/Gas Mark 2. Heat the oil in a casserole and add the bacon, onion and garlic. Cook over a medium heat until soft. Add the beans, then the passata, plus enough water to cover the beans by 3cm/1¼ inches. Add the molasses and bring up to a simmer. Cover, place in the oven and bake for about 3 hours, until the beans are tender. You may need to add more water to prevent them drying out. About half an hour before you eat, add the mustard and Worcestershire sauce. Finally, add a little salt to bring out the flavour of the beans. Eat with fried eggs or any type of hot sausage, including black pudding.

Pinto Beans and Venison

The suet in this dish is optional but it does give it an amazing flavour. This is a good braise to eat with polenta or wild rice. Alternatively, serve with boiled long grain rice, or sourdough bread that has been brushed with oil and toasted.

Serves 6

225g/8oz pinto or Mexican black beans

1 tablespoon beef dripping or extra virgin olive oil

1kg/2¼lb venison, cut into

1cm/½ inch cubes

2 heaped tablespoons grated beef suet (optional)

2 onions, finely chopped

4 garlic cloves, chopped

4 chipotle chillies, soaked in hot water for 30 minutes, then deseeded and chopped

2 teaspoons ground cumin

½–1 teaspoon cayenne pepper (to taste)

½ teaspoon ground cloves

600ml/1 pint beef stock – plus more to make it soupy, if necessary (see here)

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Soak the beans in plenty of water overnight or for 24 hours. The next day, drain the beans and put them in a pan. Cover with fresh water, bring to the boil and simmer for 1–1½ hours, until tender. Drain and set aside.

Heat the dripping or oil in a large casserole (preferably cast iron) and brown the meat well over a reasonably high heat. Lower the heat, then add the suet, if using, plus the onions, garlic, chillies and spices and cook for 2–3 minutes. Cover with the stock and simmer with the lid partly on for approximately 1 hour, until the meat is tender. Add the beans and cook over a very low heat for 15 minutes. Skim off any fat that floats on the surface. Taste for seasoning and serve.

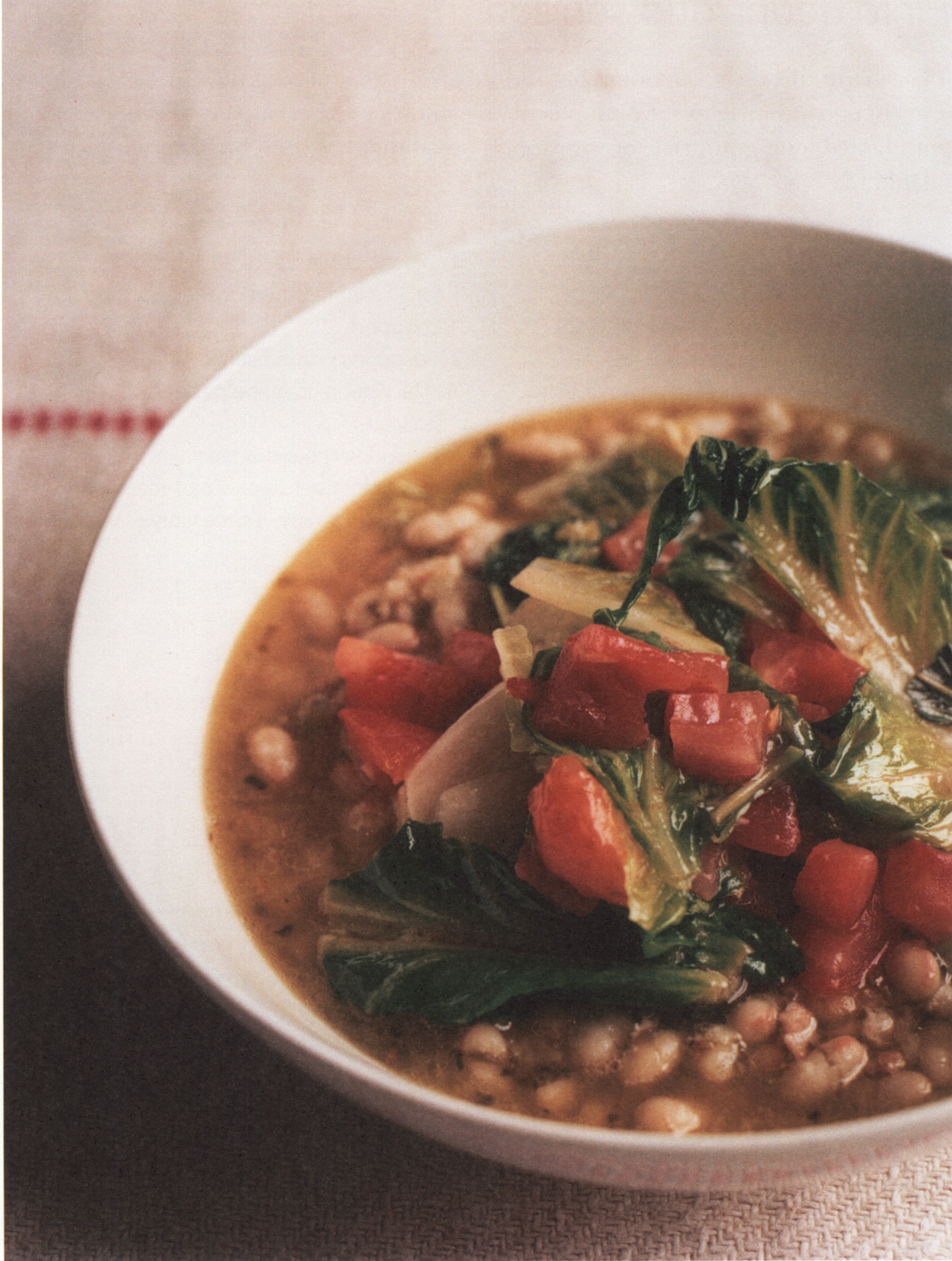

White Bean Broth with Buttered Tomato and Lettuce

White beans make textured soups that keep their elegance. They are the favourite bean of Italian cooks for this purpose. They have a mild, slightly floury taste and texture that absorbs the flavours of other ingredients.

Use cannellini beans or white haricots for this soup. Haricots are usually only available dried; they are a round bean, staying firm and smooth even after a long simmer in the pan. Cannellini are kidney shaped and can become quite soft. They are the better choice for busy cooks, since canned ones are easily available. The best lettuce to use is Cos, sometimes called Romano, or the heart of any other large-leaf lettuce.

Serves 4

4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves, chopped

1 white or red onion, finely chopped

1 celery stick and leaves, chopped

1 small fennel bulb and leaves, chopped

1–2 pinches of dried oregano

2 cans (about 470g drained weight) of white cannellini beans, drained – or use 200g/7oz dried haricot beans, soaked in cold water overnight, then simmered in fresh water for 1–1½ hours, until tender

1.2 litres/2 pints vegetable or meat stock (see here, here and here)

sea salt

To serve:

55g/2oz butter

1 garlic clove, chopped

4 small Cos hearts, cut into quarters, or the hearts of 2 larger lettuces, roughly chopped (use the outer leaves for salad)

4 plum tomatoes, skinned and diced

4 tablespoons grated Twineham Grange cheese (English Parmesan), or a hard ewe’s milk cheese such as Lord of the Hundreds or Somerset Rambler – or real Italian Parmesan

a small handful of basil leaves

a little extra virgin olive oil

Heat the oil in a large pan and add the garlic, onion, celery, fennel and oregano. Cook over a low heat for about 2 minutes until their edges begin to soften. Add the beans and stock and bring to the boil. Cook for about 5 minutes, then taste for salt.

Melt the butter in a separate pan, add the garlic and lettuce hearts and cook gently until soft; add the tomatoes and stir once. Divide the soup between 4 serving bowls and spoon the lettuce-tomato mixture on top. Scatter the grated cheese over the top with the basil. Shaking over a few drops of extra virgin olive oil will turn up the flavour.

Bean and Herb Salads

Plain cooked beans, either drained straight from the can or from a store you have prepared yourself, can be mixed with herbs, olive oil and lemon juice then seasoned to make a salad that can be eaten with almost anything. I tend to choose either white haricot beans or cannellini beans for this job because they have the tenderest skins. You can make an exotic and piquant version, however, with black Mexican beans (unavailable canned but will cook in about an hour), chopped grilled peppers, garlic, red chilli and coriander. It is very important not to overcook the beans. Their skins should remain intact and the ‘kernels’ inside must not be floury but should have a little bite to them.

Quick Braised Butterbeans

I can buy tins of butterbeans from the late-night grocer’s across the road. Drained, then flung into a pan with a couple of tablespoons of olive oil, a chopped garlic clove and spring onion, a teaspoon of organic Marigold stock powder and a little water, they make a bean stew in no time. I throw over a chopped hot red chilli, shake on some extra virgin olive oil, then eat them from a bowl.

BEEF

The cheap cuts

Grilled Goose Skirt with Salad Leaves and Berkswell Cheese

Top of the Rump with Lemon and Parsley Butter

Flank with Tarragon Butter Sauce

Braised Shin of Beef with Ale

Cold Salt Beef and Green Sauce

The valuable cuts

Roast Rare Aged Beef Sirloin with a Mustard and Watercress Sauce

Raw Beef with Horseradish, Sorrel and Rye Bread

Leftovers

Beef with Horseradish Sauce on Crisp Bread

Beef with Pumpkin Seeds and Carrot

Sauce for Pasta

Braised Beef and Fungi

Beef Stock

Dripping

My attitude to beef has recently moved into a new phase. It is easy to pinpoint when my original decision to eat less but better beef was made, because it was at the same time that I had the urge to write about food. My first piece 15 years ago was about a butcher. At the time I was motivated by the plight of the closing high-street butcher’s shops. They were – on the whole – the best place to source delicious beef, but they were closing down due to the arrival of the larger ‘superstores’. I was equally motivated by the matter of welfare: free-ranging animals, travelling only a short distance to the slaughterhouse, produce beef with a low PH and so more tenderness. When livestock are stressed, the acidity in their muscles is raised, affecting the finished result when cooked. But then, a year later, the BSE scandal exploded, when the link was made between the cattle disease bovine spongiform encephalitis and the human form, vCJD, and the whole subject of beef once more needed some examination. Two significant events had come to light. The first was that, revoltingly, beef animals had been fed the remains of their own species. This had been done purely in the name of profit – give an animal high-protein feed and it will grow at an alarming rate, becoming ready for slaughter, with lots of meat on its bones, nice and quick. The full, disgraceful disclosure of the participation of the livestock feed industry and the attitude of the Ministry of Agriculture (now Defra) and many (but not all) farmers was mind-blowing. The second significant event was the remedy introduced by the authorities to wipe out the disease in the British herd.

Meat changed by a scandal

The remedy dreamt up by the Ministry and its scientific advisers became known as the Over-Thirty-Month Scheme (OTMS), and simply meant that no cow – dairy or beef – was allowed to live longer than 30 months, because scientists said that the disease only developed in animals over this age. This had the peculiar effect of shortening the time farmers had to fatten up their beef steers, putting them under pressure in a way that has damaged the quality of beef and the national herd itself. Every farmer had to comply with it, including the substantial number who had never fed their beef animals meat and bone meal. It is not known whether the OTMS was actually responsible for reducing the number of cases; it was rumoured to be the idea of the supermarket chains, which wanted a clear-cut strategy that would boost consumer confidence.

It is nearly impossible for farmers to get their beef animals up to a saleable weight in just two and a half years. So what can they do? They can’t feed meat and bone meal protein, because that is now banned – so in comes the cereal diet: soya, maize and other grains that are high in proteins and speed up growth. They then cross breeds with large, fast-growing Continental-type cattle and take the animals off that windy hill where they burn up far too many calories, instead making sure they spend more time in the shelter of a barn, getting pig-fat. Out of this the consumer gets flavourless, loose-grained meat, unsuitable for British butchers’ cuts (the only exception is when butchers take the trouble to hang the meat on the bone for as long as possible). Consumers are further compromised because such beef, even though cross bred with non-native cattle, is still called by its British breed name – Aberdeen Angus, for example.

This news has altered my view of beef again. I now choose beef guided by three principles:

Slow grown means that, where possible, I buy ‘aged’ beef that is over 30 months old – the OTMS was lifted in November 2005. The farmers who rear such beef must jump through hoops to do this: completing extra paperwork, moving livestock in separate transportation from others, and using abattoirs specially dedicated to the slaughter of older animals. Farmers who produce ‘aged’ beef complain that it is hard to profit from the extra effort, but the resulting meat is well worth it in terms of flavour. What really matters now, however, is the third principle: grass fed. Feeding beef animals grass ticks all the boxes in terms of healthy environment and healthy consumers.

Grass-fed beef is good food. The fat that is marbled through it contains higher levels of essential omega-3 fatty acids, including the nutritionally important EPA and DHA. Beef animals fattened on a high-protein (from grain such as soya and maize), high-energy diet, rather than on grass, will have a low ratio of omega-3 in their fat compared to other fats. To be healthy, humans need to eat fats in the correct proportion or the risk of disease, specifically heart disease, is increased. It is now thought that it is not so much burger culture that made one in four Americans fat and unhealthy but the way in which beef steers were reared. Eating meat containing the right balance of the right fats raises dietary levels of conjugated lineolic acid (CLA), protecting against cancer and – essentially – discouraging weight gain because our bodies know exactly how to process such fat: burning it and not storing it as body fat.

US beef farmers are great proponents of maize feed, and ‘park’ their cattle in ‘feedlots’ – sheds or grassless fields where they are literally stuffed with maize. If you have been fed beef with yellow fat, you will recognise this beef. In the UK there is often that depressing sensation as you drive through the countryside that the crops growing in fields are mostly there to feed animals and not you. Even the wheat in the field could be for the feed bin rather than the bread bin. Compare the amount of pasture you see to the quantity of grain crops. We also import great quantities of cereal across the Atlantic to feed livestock, especially soya – much of it GM – which is high in protein and used to fatten beef animals before slaughter.

Feeding cattle grass slows down their growth. If it were the only feed available, there would be fewer beef animals on the market. We would be healthier, and so would the economy, unburdened by the cost of an obesity epidemic. However, the price of all beef would rise steeply towards the price now paid for organic and grass-fed beef. This is unavoidable, but using beef differently in the kitchen will help offset the cost. Learn to identify which are the cheap cuts to enjoy regularly and which are special. Pay more but make better use of the beef you buy. Use up leftovers, learn ways with cold beef, make stock and cook with the dripping (see here).

Buying beef

For beef to cook well, it must be hung properly. Hanging beef on the bone in temperatures just above 2°C breaks down the tough fibres – the meat is slowly decomposing. Beef should be hung for at least three weeks but I have bought joints from sides that have hung for up to five weeks. This beef will be visibly darkened by oxidisation on the outside but don’t be put off – it will taste delicious. Always ask if the beef has been actually hung and not matured in plastic bags stacked in a freezer. This method never has the same effect but meat is increasingly matured this way, partly due to new regulations that insist that the cuts destined to be beef mince should not be hung for as long as the roasting joints. This means the sides have to be cut up and jointed early, and cannot physically hang.