Полная версия

The New English Table: 200 Recipes from the Queen of Thrifty, Inventive Cooking

Buying asparagus

To find your nearest asparagus grower, see www.british-asparagus.co.uk (tel: 01507 602427). To find a farmers’ market, check your local council website or www.lfm.ore.uk for London markets.

For mail-order asparagus, contact Sandy Patullo, who grows exceptional asparagus and sea kale (another delicious edible stalk) in Scotland: Eassie Farm, By Glamis, Angus DD8 1SG; tel: 01307 840303.

All the major supermarkets sell British asparagus in season.

Asparagus with Pea Shoots and Mint

Pea shoots are an established vegetable now. They have been stocked by Sainsbury for the past three years and I often see them in markets. They are increasingly available in good food shops, too, and you can get them via mail order from Goodness Direct (www.goodnessdirect.co.uk; tel: 0871 871 6611).

When they are cooked – lightly fried in a little oil or butter, or even steamed for a minute – they have all the taste of a good, sweet garden pea, or indeed a frozen pea, but with the added bonus of being lively plants. They appear around the same time as English asparagus and, while I am always happy to eat asparagus plain, the combination of the sweetness in the pea shoots and the unique grassy flavour of the asparagus is joyfully vernal.

Serves 4–6

1kg/2¼lb new-season asparagus

2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

4 punnets of pea shoots

a few small mint leaves

finely grated zest of ½ lemon

sea salt and freshly ground white pepper

For the sauce:

1 shallot, chopped

a grating or two of nutmeg

2 wineglasses of white wine

1 teaspoon white wine vinegar

225g/8oz unsalted butter, softened

Pare away the outer skin of each spear, taking off about 6cm/2½ inches from the base of the stem. Bring a large, shallow pan of water to the boil. Before cooking the asparagus, however, make the sauce. Put the shallot, nutmeg, white wine and white wine vinegar in a small saucepan and bring to the boil. Cook until the liquid has reduced to about 3 tablespoons, then strain it through a sieve and return it to the pan, discarding the shallot. Add the butter, about a teaspoon at a time, whisking it into the liquor over a low heat. When all the butter has been used, the sauce should be thick and creamy.

Add the asparagus to the pan of boiling water; it will need about 5 minutes’ simmering to become just tender. Meanwhile, put the oil in a small frying pan and fry the pea shoots in it until they collapse slightly.

Using tongs, lift the asparagus out of the water and drain on a cloth (I find asparagus breaks up if you tip it into a colander, and that it needs the cloth to get rid of excess water, which can make it soggy). Divide the asparagus between 4–6 warm serving plates and heap the pea shoots over the tips. Give the sauce one final whisk over the heat to amalgamate it (it will split a little if left, but it will ‘come back’), then pour it generously over the asparagus. Season with a little salt and pepper and scatter the mint leaves and lemon zest over the top. Eat immediately and, if you are in festive mode, serve as a starter before Fried Megrim Sole or the lamb with spring vegetables.

Boiled or Steamed Asparagus

I cook asparagus loose, either in boiling salted water in a shallow pan or in a steamer. Today’s varieties seem to take only about 5 minutes for a thick stem. If you have time, pare away the outer skin of the spears up to about 6cm/2½ inches from the base before cooking. This enables you to eat the whole spear, and allows the butter to sink in. Melt about 30g/1oz butter per person, pour it over the cooked asparagus and serve with loose sea salt.

BACON

Bacon and Shellfish

Bacon and Potatoes

Bacon Gravy for Sausages

Light Bacon Stew

Bacon and Apples

Bacon and Potato Salad with Green Celery Leaf and Cider Vinegar

Unhappiness reigns if there is no bacon in the house. It is my mainstay meat, the inexpensive strip of flesh that is the difference between having nothing to cook with and the ability to produce a meal quickly for everyone. It glamorises and adds body, not least its great and addictive flavour, to things such as lettuce and spring greens, and it keeps for weeks.

But be fussy about the bacon you buy. The food industry’s record in the cheap pig meat business is abysmal on both welfare and quality grounds. Pigs reared intensively in Holland and Denmark, major providers of budget pork products to the UK, suffer some unacceptable conditions. Two-thirds of sows (mothers) are tethered and confined in stalls with hard, slatted floors for all their lives. The idea is to make pig rearing super efficient and tidy, to the miserable detriment of the pigs themselves. They are no more than breeding machines, expected to shoot out three litters a year until their bodies pack up. Stalls and tethers are not permitted in indoor pig farms in the UK but sows are kept in farrowing crates during birth and for four weeks after, before being transferred back to a pen – a system that is not ideal but is less cruel. Feed for pigs in both systems is high protein, often heavy in soya (these omnivores consume little flesh), which grows the animal to its bacon weight in swift time so that it will become a highly profitable pig. Processing this meat into bacon, and maximising profit, means injections of brine and phosphates; liquid that you will see seeping from the rasher as it cooks. A big, heavy pack of Danish bacon, the supposed great budget buy, will become shrunken watery slivers in the pan. It is hard to see what is economical about that for the consumer but we assume the industry that produced it is laughing all the way to the till. There is better value in a pack of best smoked streaky from a pig that has been kindly and naturally reared; best of all, if the streaky is cured on the butcher’s premises. Ask for it to be sliced very thinly, so that all the rind is edible and the bacon cooks to a crisp stained-glass window in just a few minutes. Back rashers have their place, too, and it is good to have both cuts at the ready. Smoked bacon tends to be less salty, as it goes through two curing processes, and its flavour pervades other ingredients in recipes in a non-aggressive way. But these flavour comments are personal. Like tea, everyone likes bacon in a different way.

Buying bacon

Buy dry-cured bacon made as near as possible to your home. Ask butchers where they source either the bacon they sell or the pork they make their own from. If you cannot buy anything local, one of the best bacons via mail order is made by Peter Gott, at Sillfield Farm near Kendal in Cumbria (www.sillfield.co.uk; tel: 015395 67609). The flavour of his dry-cured bacon and ‘pancetta’ is beautifully balanced, and is made with pork from free-range rare-breed pigs and wild boar. Furness Fish, Poultry and Game Supplies deal with the mail order: www.morecambebayshrimps.com; tel: 015395 59544.

Bacon and Shellfish

Bacon can switch from being stock food to something exceptional when it is put in the pan with one of its most natural partners. Spend a happy hour piling through a bowl of shell-on North Atlantic prawns that have been added, at the last minute, with 2 tablespoons of butter to a frying pan of bacon. Throw over a handful of chopped dill as you serve. Big king scallops, griddled on a hot plate, can be put on the same plate as streaky bacon ‘sugar canes’: rashers of very thin bacon that are twisted before being roasted in the oven or cooked in a pan over a medium heat for 10 minutes. Serve the scallops and bacon with small beet leaves or baby chard. Tabasco on the table – as it often seems to be.

Bacon and Potatoes

A rasher of bacon, wrapped around a lump of butter or cream cheese with chopped parsley and placed inside a part-baked potato, will, once returned to the oven wrapped in foil for a further 20 minutes’ cooking, make a supper eons more exciting than a wrinkled brown pebble with a sad lozenge of butter sliding around on the top.

Bacon Gravy for Sausages

I use bacon to make instant onion gravy for bangers and mash when I have no stock. Put a chopped rasher into the pan with a chopped onion, add a little butter or oil and cook over a low heat until the onion turns golden. Add a teaspoon of flour, stir well over the heat until it browns a little, then slowly add about 150ml/¼ pint water, stirring all the time. The result is a pale, buff-coloured sauce, not gravy brown, but it tastes fine.

Light Bacon Stew

Smoked pork belly can be cut into chunks, browned in a pan with garlic, onion and celery, then simmered in stock until tender. Serve with boiled potatoes and plenty of parsley. If you have any joints of poultry or fresh rabbit, add and simmer with the bacon.

Bacon and Apples

An easy small lunch dish that can be woven into a plate of cooked yellow lentils and a slice of Appleby Cheshire cheese. Nearly perfect. It will be no good, though, made with any one of that terrible trinity of juice bombs – Gala, Braeburn or Granny Smith – and, sad to say, Bramleys will fall to bits. Cox’s Orange Pippins are best, or another apple with a good, fibrous texture and matt skin (see here).

I prefer to use thinly cut smoked streaky bacon for this, but if you like a thick cut, or prefer to use back or middle rather than streaky, that’s fine, too.

Serves 2

a large knob of butter

4 rashers of smoked streaky bacon, cut into 2cm/¾ inch strips (remove the rind first if they are cut thick)

2 eating apples, cored and cut into segments

light brown muscovado sugar

freshly ground black pepper

Melt the butter in a frying pan, add the bacon and cook until it loses its transparency and becomes crisp. Add the apples and fry both for 4–5 minutes until the apples are tender, gently turning them occasionally but not too often or they will break up. Sprinkle a pinch of muscovado sugar over the apples, then twist over some black pepper. With the bacon, salt is not needed.

Serve with yellow-brown Umbrian lentils – cooked as for green lentils but substituting real ale, more stock or water for the wine.

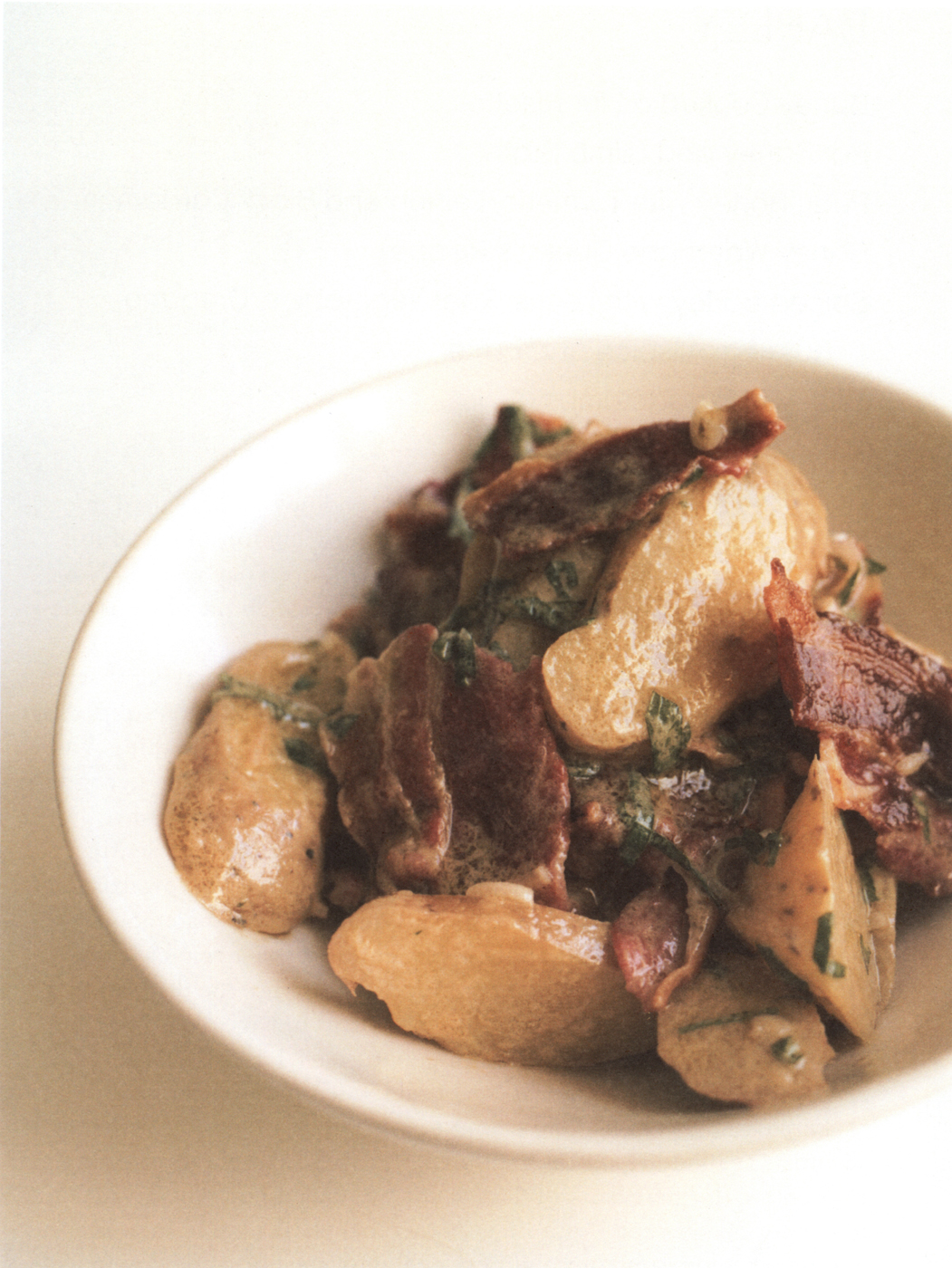

Bacon and Potato Salad with Green Celery Leaf and Cider Vinegar

Be sure to chop the celery leaves finely for this warm salad so there is all the flavour and no fibrous texture. This is a perfectly good and economical dish to eat alone – the bacon means you need no other protein, but you could follow it with some cheese and buttered oatcakes.

Serves 4

20 new potatoes

6 rashers of smoked streaky bacon. cut very thin, or the rind cut off

1 teaspoon sugar

1 tablespoon Dijon mustard

175ml/6fl oz light olive oil or sunflower oil

1 tablespoon cider vinegar or apple vinegar

2 tablespoons water

a handful of celery leaves, finely chopped

2 shallots, chopped

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Cook the potatoes in boiling water until just tender but not too soft. Drain, cut each one in half and set aside. Meanwhile, cut the rashers in half and put them in a frying pan (with no fat). Place over a medium heat and cook for about 10 minutes, turning once or twice, until crisp as a cracker.

Put the sugar, mustard, oil, vinegar and water in a bowl and mix until well emulsified. Stir in the celery leaves and shallots. Taste and add salt if necessary, then season with black pepper.

Put the potatoes in a big bowl, throw the crisp rashers over the top and pour over the dressing. Mix well. It doesn’t matter if the rashers break up – that way it just tastes better.

BARLEY

Barley Cooked as for Risotto

Pot Barley and Lamb Broth

Pearl Barley with Turmeric, Lemon and Black Cardamom

Barley Water (the Queen’s Recipe)

Spiced Barley with Leeks, Root Vegetables, Oregano, Nutmeg, Allspice and Butter

Barley in Breadcrumbs

Superseded by wheat in almost all recipes, and now mainly used in brewing, barley is an ideal grain to rediscover from the annals of lost food plants and bring back into use in modest, everyday recipes. Now is a good time to think about eating grains other than the obvious ones, and to enjoy as many food plants as possible.

Before getting on to the science bit, I have to start by saying that since using new grains in my kitchen, life has got a lot more interesting. After years of pasta, risotto and pilav, suddenly I am tasting something with a totally new feel, scent and taste. I am yet to get some of these new grains past my children, who are happier to fork up basmati and penne. But my mother, who tried to feed us the then unfashionable Puy lentils in the 1970s, provoked a memory that must have steered me towards them when they properly arrived on the scene nearly 20 years later. So now when I put the new grains on the table and hear the inevitable refusal from the children, I know that they hear adults praise the dish, and I hope their curiosity will one day provoke them to have a try. I am sure they will do it when I am not looking, but I have learned that there is no point in making a child eat something when they are not ready.

Discovering, cooking and eating new grains matters. According to scientists at Biodiversity International, the organisation campaigning to preserve the gene bank of ‘lost’ foods, we depend on wheat, rice and maize for 50 per cent of our diet – a fact that challenges human health and opens to question our ability to deal with the effects of climate change. They say that people who eat more diverse diets are less prone to killer diseases, such as cardiovascular illness, cancer and diabetes. They also claim that avoiding the bank of over 7,000 edible plants means we miss out on essential nutrients.

It’s a bit of a tall order to expect anyone to keep 7,000 foods in their larder, but the basic message is that the balance of our diet has been lost. Daily bread should not always be wheat but occasionally another grain or, better still, a combination of several. In terms of the environment, demand for a diverse diet encourages more innovation in agriculture. The monoculture dominated by wheat, rice and maize is vulnerable to disease and pests but widening the range of crops ‘confuses’ these threats – one crop’s enemy is not that of another. A pest that destroys a certain breed may not touch others. Hence less need to treat with pesticides, a longer season (given that different strains of species ripen at intervals) and so more food. There is also evidence that cultivating a greater number of grains, vegetables and fruits can benefit the wealth of farming communities in developing countries. It’s obvious, though, isn’t it? With just three main grain plants dominating the food chain, and every country fighting to make money from farming and be a part of the global marketplace, there are going to be those at a natural disadvantage – namely those farmers who do not receive subsidies and nations who pay levies on exports.

In the UK, the range of grains we can include in our own diet includes rye, oats, spelt and the various strains among these species. Likewise we could expand our repertoire on the vegetable and fruit front, too (see Apples). Barley is a good starting point. It is the oldest cultivated grain in not only Europe and the Middle East but also possibly the world. Some historians believe that it may have been grown in China before rice. Looking at my store of pearl and pot barley, I wondered about this. Pearl barley, like white rice, has had all the bran milled away, leaving a mild-flavoured grain; pot barley still retains some bran, whose oils turn up the flavour volume. Barley has lower protein levels than wheat, hence its gradual decline – it was thought the poor could never be fed on such a grain – but it is sad to miss out on its delicate nature. Why not use it in a recipe and divert attention away from rice for a change?

Buying barley

Pearl barley is available in every supermarket but you may have to go to a wholefood store for pot barley – the one with the bran. The Infinity Foods brand of organic pot barley is widely available (www.infinityfoods.co.uk; tel: 01273 424060).

Barley Cooked as for Risotto

White pearl barley can be treated in exactly the same way as Arborio rice to make an Italian-style risotto. For 2 people, melt a tablespoon of butter in a heavy-bottomed pan, then add 1 finely chopped shallot. Cook for a minute, then add 150g/5/½oz pearl barley. Cook for another 30 seconds, then pour in a wineglass of white wine and bring to the boil. Begin to add either chicken, vegetable or veal stock a ladleful at a time, allowing the barley to absorb the stock before adding more. When the barley is tender, beat in another tablespoon of butter. Season with salt and pepper and serve with grated cheese. For an indigenous dish, use a British hard, aged ewe’s milk cheese, such as Lord of the Hundreds or Somerset Rambler, or a cow’s milk cheese such as Twineham Grange (a Parmesan taste-alike made in the southeast). Add a vegetable, if you wish – the green kernels of broad beans, or Cos lettuce. The barley would also be good with shellfish, omitting the cheese: add North Atlantic prawns at the second butter stage, first using their shells to make the stock that ‘feeds’ the barley.

Pot Barley and Lamb Broth

More soup to eat regularly, leaving a store of it in the fridge and returning to it until it is finished. This time a broth, heartened with lamb or mutton. You don’t want a soup that is too thick and grainy here but a clear, brown broth, with just enough pearl barley to make it a lunch. The sauce will brighten it, dragging a winter dish into spring. If you use mutton instead of lamb, be aware that there is often a lot of fat on it. If you make the broth the day before you eat, skim off the hardened fat but leave a little – it is not only very good for you but carries a robust, muttony taste.

Serves 4

1 teaspoon dripping

1kg/2¼ shank of lamb, or mutton (neck, shank), including the bone

1 large carrot, roughly chopped

1 onion, roughly chopped

1 celery stick, roughly chopped

1 bay leaf

1 sprig of thyme

6 tablespoons pearl barley

sea salt

To serve:

1 garlic clove, peeled and cut in half

4 sprigs of flat-leaf parsley, very finely chopped

3 tablespoons olive oil

freshly ground black pepper

Heat the dripping in a large casserole, add the meat and brown on all sides. Add the vegetables and herbs, then pour in enough water to cover and bring to the boil. Skim away any foam that rises to the surface. Simmer for about 1½ hours, until the stock has taken on the flavour of the lamb – taste it – and the meat is falling from the bone. Strain the contents of the pan through a large sieve or colander, retaining the broth. Put the broth back into the pan. Discard the vegetables and herbs and pick the meat off the bone. Add the meat back to the pan with the barley. Bring to the boil again and simmer gently for 25 minutes, until the barley is cooked. It should be slightly chewy in the centre. Taste the broth and add salt if necessary. Skim off any surplus fat.

Rub the garlic clove around the inside of a small bowl to release its juice but no flesh. Add the parsley, oil and black pepper and stir. Add a teaspoon to each bowl of hot broth as it is served.

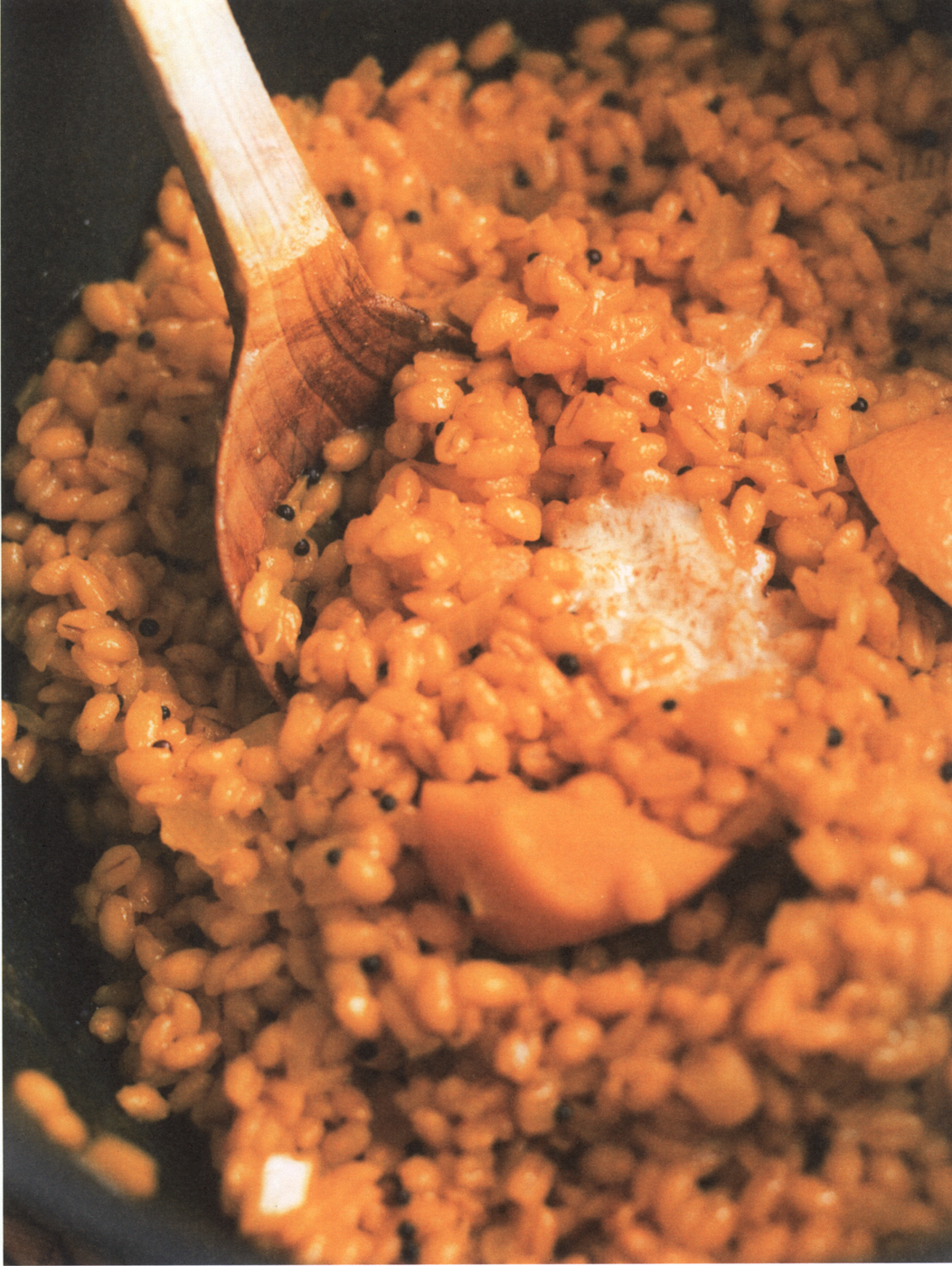

Pearl Barley with Turmeric, Lemon and Black Cardamom

We eat this as an alternative ‘lemon rice’ with curries and dals, or with grilled meat and fish. It is quite possible to adapt this recipe to other grains, such as basmati rice, oat groats, spelt grains or quinoa, if you wish. I like the feel of barley in the mouth – little springy cushions of grain that easily absorb the flavours of whatever they are cooked with.

Serves 4

2 tablespoons sunflower oil

1 white onion, finely chopped or grated

1 teaspoon black mustard seeds

1 black cardamom pod

2 level teaspoons ground turmeric

200g/7oz pearl barley

juice of ½ lemon

sea salt

Heat the oil in a pan, add the onion and mustard seeds and cook over a medium heat until the onion begins to take on some colour – the mustard seeds will make a popping sound. Add the other spices, stir and add the barley. Stir the barley to coat it with the oil and spice mixture, then pour in enough water to come just over 1cm/½ inch above the surface of the barley. Bring to the boil, cover the pan, then turn the heat right down and cook for 25 minutes. Have a peep from time to time – you may need to add a little more water if it is becoming too dry.

When the barley is just tender, add the lemon juice, then taste and add salt if necessary. Try to avoid eating the black cardamom – while it smells heavenly, it is a nasty thing to chew.

Barley Water (the Queen’s Recipe)

Jeremy Lee is a chef who likes to be called a cook. He grew up with good food in his mother’s kitchen and is now dedicated to making it for others. Since meeting him and eating at his restaurant, the Blueprint Café in London, I have been awed by his knowledge, and love his simple approach to good ingredients. He is one of those chefs who resist the temptation to add another ingredient to a dish, and he makes a mustardy salad dressing that will activate your tear ducts at 20 paces. The table and cooking of his mother, Eileen Lee, must have rubbed off; you will always find bottled fruit and pickles lined up on shelves in his restaurant and they are not there for décor. Eileen died suddenly in 2006 but, during a conversation that strayed inexplicably to barley (my, how you’d enjoy my company), Jeremy told me about the barley water she would make for her ‘little clucks’, keeping it in a glass jug in the fridge. ‘The recipe, which was called the Queen’s barley water, was pulled from a newspaper,’ he wrote when he sent me the recipe. ‘It was so refreshing, nourishing and also very good for your skin.’ Making it yields a nice little by-catch – a dish of barley to dress with olive oil, shallots and herbs.

225g/8oz approx. pearl barley

2.5 litres/4 pints water

6 oranges

2 lemons

Demerara sugar to taste

Wash the barley well. Tip it into a pot and cover with the water, then bring to the boil. Lower the heat to a gentle simmer and cook gently for up to an hour, until the barley is tender. Strain the barley (reserve it for another dish) and leave the liquid to cool. Stir in the grated zest of 3 oranges and 1 lemon, then the juice of all the fruits. Add sugar to taste; it should not be too sweet. Pour into a jug and keep in the fridge, drinking within a day or two.