Полная версия

The New English Table: 200 Recipes from the Queen of Thrifty, Inventive Cooking

Serves 4

200g/7oz buckwheat groats

4 large or 8 small herring fillets

1-2 eggs, lightly beaten

sunflower oil

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

For the sauce:

2 egg yolks

2 teaspoons Dijon mustard

300ml/½ pint light olive or sunflower oil

lemon juice, to taste

3 hardboiled egg whites, chopped (see Kitchen Note below)

1 tablespoon capers, rinsed, squeezed and chopped

5 cornichons (baby gherkins), chopped

1 shallot, finely chopped

leaves from 1 sprig of parsley, chopped

leaves from 2 sprigs of tarragon, chopped

leaves from 2 sprigs of chervil, chopped (if available)

First make the sauce. Put the egg yolks in a bowl with the mustard, then gradually whisk in the oil bit by bit until you have a thick emulsion. Add the remaining sauce ingredients, taste and add a pinch of fine sea salt if necessary. Set to one side.

Season the groats with salt and pepper. Dip the herring fillets in the beaten egg, then roll them in the buckwheat groats. Pour enough oil into a heavy-bottomed frying pan to cover the base well. Heat the oil and fry the herrings over a medium to high heat for about 2 minutes on each side, until the groats are golden and the fish is firm. Eat hot, with the sauce.

BUFFALO MILK

Buffalo Milk Yoghurt with Lavender Honey and Pear Salad

There has been an invasion, a friendly one, that has won the hearts and minds of food lovers everywhere. Buffalo roam the English fields – but not the entire countryside, thank goodness. They like to wallow to cool their muscles and, while it is a cute sight to see their ears and nostrils poking above the water in rivers and shallow ponds, it is a terrible job for the herdsmen to winch them out of their happy, wet haven and milk them.

Milking is the best possible use for them. Their meat is almost fatless, which makes it attractive to some, but I’d rather eat native beef with its marbling of fat, and on other days, buffalo yoghurt and cheese. Buffalo milk is a little volatile – it needs to be very fresh when made into yoghurt or fresh cheese, or it will have an overripe flavour that can be off-putting. I am not a milk drinker, so turn it into a rich, creamy, white-as-chalk yoghurt and serve it with flower honey and ripe pears – a healthy breakfast, but I would not be at all ashamed to put it on the table as a hurried pudding after lunch. There’s no need, if you are short of time, to arrange it on plates as in the recipe below. Instead, just let everyone d-i-y. The yoghurt can go, ice cold, into a large earthenware bowl with a ladle, the honey on the table and a bowl of pears.

Buying buffalo milk

Higher Alham Farm, near Shepton Mallet, produces milk, yoghurt and an excellent, not quite authentic, organic buffalo cheese to eat fresh with salads. Its products are available at Pimlico, Notting Hill, Stoke Newington and Archway farmers’ markets in London. Mail order is available for a minimum quantity: www.buffalo-organics.co.uk; tel: 01749 880221.

Buffalo Milk Yoghurt with Lavender Honey and Pear Salad

To make the yoghurt, you will need four 250ml/9fl oz jars, spotlessly clean, and a warm place such as an airing cupboard. Automatic yoghurt makers are available from Lakeland Ltd (www.lakeland.co.uk; tel: 015394 88100).

You can, of course, buy the yoghurt, or use a good whole dairy milk brand that you are devoted to, but …

Serves 8

1 litre/1¾ pints fresh buffalo milk

4 tablespoons live yoghurt

For the lavender honey and pear salad:

6 Cornice pears, peeled, quartered and sliced

juice of ½ lemon

2 heaped tablespoons lavender honey

a few lavender buds, if available

Warm the milk to boiling point, then leave it to cool to just above blood temperature – about 38°C/100°F. Stir in the live yoghurt and put it into jars. Seal and put in a warm place (about 29°C/84°F) for about 6 hours, until set.

Put the pears into a bowl, squeeze over the lemon juice, then pour over the honey. Gently stir, or turn the pears over so they get a good coating of the honey, which will thin as you do this. Add a little pinch of lavender buds. Eat the yoghurt with the pear salad spooned over.

CAULIFLOWER

Cauliflower with Lancashire Cheese

Leftovers

Crisped Cauliflower with Breadcrumbs and Garlic

Cauliflower Soup

I am an admirer of cauliflower but I am not sure about anyone else. It was astonishing to hear from a farmer, standing with him in a giant cauliflower patch near Preston, that the British are colour sensitive about the vegetable. Unless it is spotlessly white, no one will buy it. On the day of my visit to this mecca of cauli growing, the sun was out and the cauliflowers were swiftly turning yellow. The farmer told me he would grub the whole lot into the ground: it wasn’t just the supermarkets who would be reluctant to buy them, the shoppers wouldn’t touch them.

On that basis, I think we need some recipes for this vegetable that, when fresh, is less sulphurous, less aggressive, more … poetic than a cabbage. Mark Twain was right when he said that a cauliflower is a cabbage with a college education.

Cauliflower with Lancashire Cheese

The cheese sauce for this dish is a basic that you can pour over other leafy vegetables to make a filling supper – try it with Swiss chard, Brussels sprouts, curly kale, spinach, lettuce hearts and beetroot tops.

Serves 4–6

1 large cauliflower, broken into chunks (use the leaves if they look fresh, slicing them into thin strips)

a pinch of ground mace or a few gratings of nutmeg

600ml/1 pint milk

1 bay leaf

40g/1½oz butter

40g/1½oz plain flour

200g/7oz Lancashire cheese, grated

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Fill a large pan with water and bring it to the boil. Add a pinch of salt and the cauliflower and boil for about 7 minutes, until just tender but not soft. Meanwhile, put the spice, milk and bay leaf into a small pan and bring to the boil. Pour into a jug and set to one side. Melt the butter in the same pan and add the flour. Mix to a paste and cook over a low heat until the paste has a sandy texture. Gradually whisk in the hot milk (having removed the bay leaf), making sure there are no lumps. Bring the sauce to the boil, stirring all the time. Add the cheese and stir once more, then remove from the heat. Season with salt and pepper.

Put the cauliflower in a shallow ovenproof dish and pour the sauce over the top. Either brown it under the grill or bake for a few minutes in an oven preheated to 240°C/475°F/Gas Mark 9, until browned on top.

Cauliflower leftovers

Crisped Cauliflower with Breadcrumbs and Garlic

I like to fry previously boiled cauliflower with fresh breadcrumbs in a little oil, with a peeled garlic clove (to be removed later), then eat it with orecchiette, the little ‘ears’ of pasta that so effectively collect the broken, crisp pieces of cauliflower and crumbs. Grate some Parmesan cheese over the top.

Cauliflower Soup

Gently fry a chopped onion in butter or oil, then add the cooked cauliflower. Season with a little English mustard powder, cover with milk and stock (50/50) and bring to the boil. Liquidise and season, then serve hot with a little cream and chopped chives – or my favourite herb, chervil, if you can get it.

Glorious Rehash – A New Generation of Leftovers

Thin, melting slices of rare roast beef, eaten with a mustard dressing tinted with anchovies and capers; cockles in a hotpot of seafood broth, served with a garlic sauce; little cauliflower florets crisped in a pan with breadcrumbs and olive oil; the lightest shrimp shell and straw mushroom broth, made warmer still with needles of fresh ginger; a radiant, creamy squash soup, flavoured with melted, brandy-washed cheese; or perhaps a dish of rice spiked with allspice and green pistachios, cooked in a pan with shards of roast lamb …

A menu that sounds richly indulgent but which is a good deed: in all these dishes there is something that might otherwise have been thrown away. Leftovers – the skeletons, shells, skins and extra flesh of foods deserving of a better future. Landfill that became a tummy full.

If you pay more for the best raw materials, it makes sense to use up every little bit. When a cut of well-hung meat from a slow-reared, grass-fed animal costs between twice and four times as much as one that was reared indoors and forced to grow fast on an unnatural diet, spreading the cost becomes an economic necessity. But this is not the only reason to reduce waste. It is estimated that one-third of the food bought in the UK is thrown away, ending up in landfill where it rots, emitting methane, a major contributing factor to climate change. The value of this food is estimated at £8 billion yearly – sympathy wanes, in certain cases, with complaints about paying more for better food.

The case for eating leftovers has not historically been helped by gloomy offerings of unidentifiable rissoles, khaki-hued ‘mystery’ vegetable soups, or bubble and squeak. An occasional plate of fried, leftover greens and mash is bearable but taken weekly it is tedious. There are other ways: using the colour and fragrance of fresh herbs from a pot on the windowsill, trying interesting seasonings, adding piquant dressings, wrapping with good bread or thin, olive oil pastry. Abandon bubble and squeak, take those cooked sprouts or spring greens, shred them and fry them instead in butter with cooked rice or whole grains of wheat; add ras al hanout, a Moroccan spice mix, then perhaps some chopped celery and shredded cold cooked chicken, game or lamb; sprinkle with black onion seeds once piping hot, then serve with creamy Greek yoghurt and fresh coriander. Suddenly you have in front of you a feast, even if one grown from humble beginnings. As for the spare cooked potato, mix it with a little potato flour and beaten egg, then make it into little patties; fry them and eat with smoked haddock, fresh peppery watercress and soured cream. Two typical leftover Sunday lunch foods become two extra, economical meals.

Broth, or stock, is the tea of bones. How can a nation that is self-confessedly addicted to tea not feel the same about stock made from chicken carcasses, beef shins, fish bones or prawn shells? Like tea, stock warms the soul and revives flagging energy levels. It is impossible not to feel good after eating food made with stock. It is even time-economic: once in the pan, it bubbles along unassisted, ready to use in an hour, or to bottle and freeze. A risotto or soup made with real stock has reserves of natural, heavenly flavour that underpin the goodness in the other ingredients and cut the need for salt. Doctors should prescribe stock – and go some way to preventing heart trouble. Casting pearls before swine may seem all too easy, but eat the pig from the tips of its toes to the end of its ears and there will be money for gems.

CELERY

Green Celery, Crayfish and Potato Salad

Celery Soup

Celery Stock

Farmers and shops are dismissive of celery – you only have to watch the harvest to witness this, which I did one horrible wet day in Cambridgeshire. It is a magnificent-looking crop, tall and leafy, its big strong heart and root deep in the Fens. But as it is pulled out of the ground, the pickers immediately cut off all or most of the heart, then lop all but a few leaves from the top, leaving just 30cm/12 inches of stalk. I have a nasty suspicion that this execution, which is not practised in southern Europe where celery is sold in its gorgeous entirety, is carried out in order that the celery head will fit in the average carrier bag. It is true that no one is quite sure what to do with celery, except use it as a base for stews or stick it in a jug and put it out with the cheeseboard.

It’s nice to emerge from a market with a mane of foliage flying out behind you, and tap into a vegetable that has a flavour I can only describe as important. Celery is as much a seasoning as a main ingredient. Even the leaves, where the flavour is at its most intense, are useful and should not be wasted.

Buying celery

The original ‘Fenland’ celery is still grown in deep furrows in the Fens, and is available from October to December in Waitrose. You can use ordinary celery in any of the following recipes, but look out for heads with leaves.

Green Celery, Crayfish and Potato Salad

Jane Grigson’s salad of mussels, potatoes and celery inspired this rare, crayfish-packed version, which I made on my return from the Fens clutching a whole celery plant saved from the picker’s knife. I fancied that freshwater crayfish roam the streams around the fields where the celery and potatoes grow, circling them. So, as it does with other things that share a landscape, like pork and apples, it seemed right that they ended up in the same bowl. The result is a fresh and unusual salad, the sweetness of the crayfish pitched against the sharp, savoury celery, with the potato in between, mopping up the dressing.

For information on buying crayfish.

Serves 4 as a main course

600g/1lb 5oz new potatoes

280g/10oz celery sticks

200g/7oz shelled, cooked crayfish

4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

juice of 1 lemon

leaves from 2 sprigs of flat-leaf parsley

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Put the potatoes in a pan of water and bring to the boil. Cook until the point of a knife will slip in with just a little resistance. Remove from the heat, drain and immediately rinse with cold water to prevent further cooking. Allow to cool, then cut into slices 5mm/¼ inch thick. Put in a large bowl.

Pull any tough strings from the celery sticks and wash off any dirt. Slice them thinly across the grain, then rinse and pat dry.

Add the celery and crayfish to the bowl of potatoes and toss together with the oil, lemon juice, parsley, some freshly ground black pepper and a pinch of salt flakes. Use celery leaves for decoration.

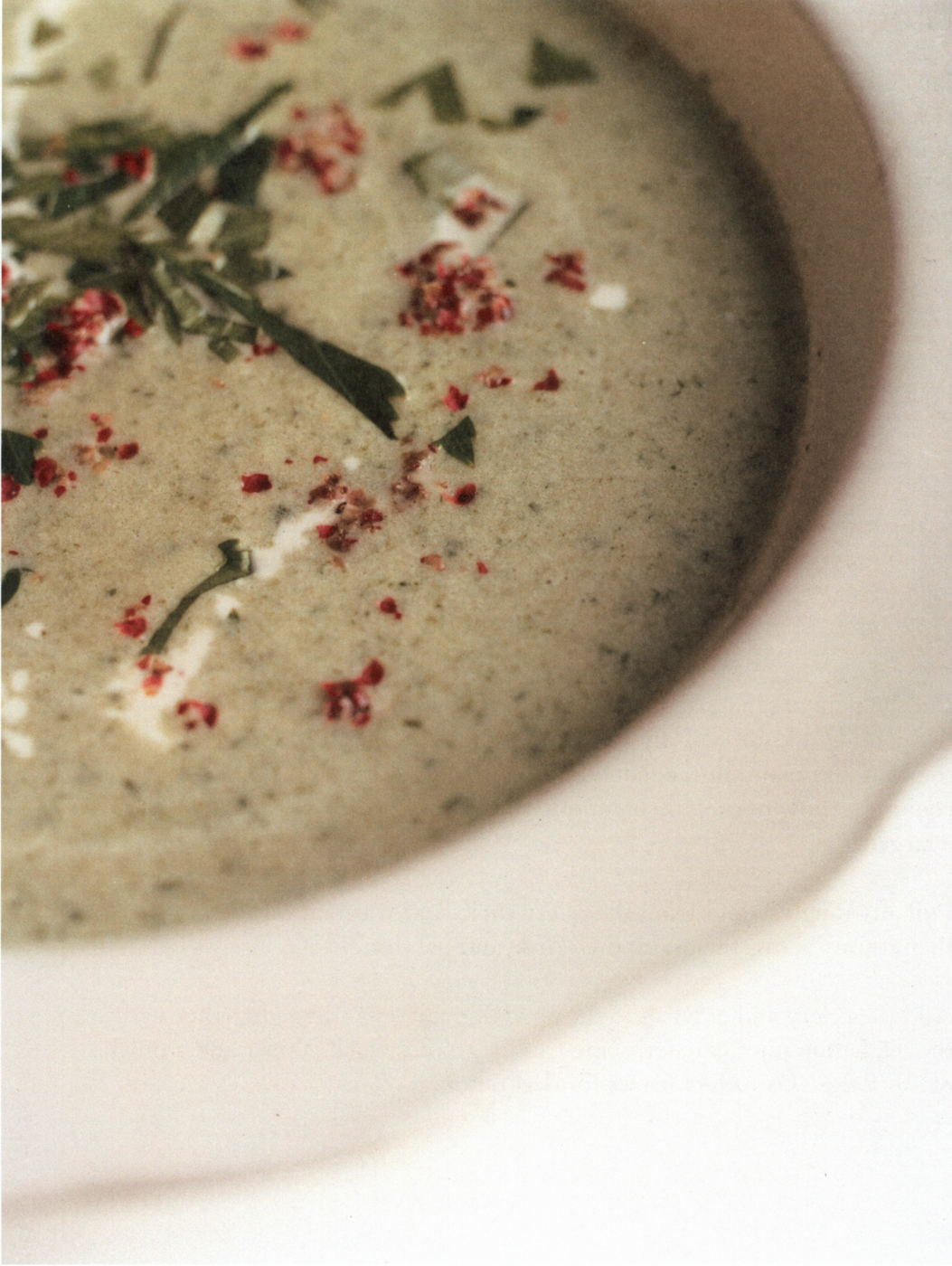

Celery Soup

Celery has awkward bits – namely the strings that run up the length of the stalks. Removing some of them will make this a smoother, creamier soup. Using a mixture of stock and milk gives it a more velvety texture still. The important part is the stewing of the vegetables in butter or oil at the beginning, because it helps to extract the maximum flavour.

Serves 6

½ head of celery, with leaves

85g/3oz butter or 4 tablespoons olive oil

2 white onions, chopped

4 medium potatoes, peeled and cut into dice

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.