полная версия

полная версияThe Illustrated London Reading Book

CULLODEN

Culloden Moor—the battle-field—lies eastward about a mile from Culloden House. After an hour's climbing up the heathy brae, through a scattered plantation of young trees, clambering over stone dykes, and jumping over moorland rills and springs, oozing from the black turf and streaking its sombre surface with stripes of green, we found ourselves on the table-land of the moor—a broad, bare level, garnished with a few black huts, and patches of scanty oats, won by patient industry from the waste. We should premise, however, that there are some fine glimpses of rude mountain scenery in the course of the ascent. The immediate vicinage of Culloden House is well wooded; the Frith spreads finely in front; the Ross-shire hills assume a more varied and commanding aspect; and Ben Wyvis towers proudly over his compeers, with a bold pronounced character. Ships were passing and re-passing before us in the Frith, the birds were singing blithely overhead, and the sky was without a cloud. Under the cheering influence of the sun, stretched on the warm, blooming, and fragrant heather, we gazed with no common interest and pleasure on this scene.

On the moor all is bleak and dreary—long, flat, wide, unvarying. The folly and madness of Charles and his followers, in risking a battle on such ground, with jaded, unequal forces, half-starved, and deprived of rest the preceding night, has often been remarked, and is at one glance perceived by the spectator. The Royalist artillery and cavalry had full room to play, for not a knoll or bush was there to mar their murderous aim. Mountains and fastnesses were on the right, within a couple of hours' journey, but a fatality had struck the infatuated bands of Charles; dissension and discord were in his councils; and a power greater than that of Cumberland had marked them for destruction. But a truce to politics; the grave has closed over victors and vanquished:

"Culloden's dread echoes are hush'd on the moors;"

and who would awaken them with the voice of reproach, uttered over the dust of the slain? The most interesting memorials of the contest are the green grassy mounds which mark the graves of the slain Highlanders, and which are at once distinguished from the black heath around by the freshness and richness of their verdure. One large pit received the Frasers, and another was dug for the Macintoshes.

Highland Note-Book.

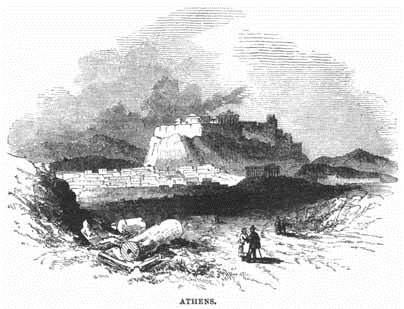

ATHENS

The most striking object in Athens is the Acropolis, or Citadel—a rock which rises abruptly from the plain, and is crowned with the Parthenon. This was a temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva, and was built of the hard white marble of Pentelicus. It suffered from the ravages of war between the Turks and Venetians, and also more recently in our own time. The remnant of the sculptures which decorated the pediments, with a large part of the frieze, and other interesting remains, are now in what is called the Elgin collection of the British Museum. During the embassy of Lord Elgin at Constantinople, he obtained permission from the Turkish government to proceed to Athens for the purpose of procuring casts from the most celebrated remains of sculpture and architecture which still existed at Athens. Besides models and drawings which he made, his Lordship collected numerous pieces of Athenian sculpture in statues, capitals, cornices, &c., and these he very generously presented to the English Government, thus forming a school of Grecian art in London, to which there does not at present exist a parallel. In making this collection he was stimulated by seeing the destruction into which these remains were sinking, through the influence of Turkish barbarism. Some fine statues in the Parthenon had been pounded down for mortar, on account of their affording the whitest marble within reach, and this mortar was employed in the construction of miserable huts. At one period the Parthenon was converted into a powder magazine by the Turks, and in consequence suffered severely from an explosion in 1656, which carried away the roof of the right wing.

At the close of the late Greek war Athens was in a dreadful state, being little more than a heap of ruins. It was declared by a Royal ordinance of 1834 to be the capital of the new kingdom of Greece, and in the March of that year the King laid the foundation-stone of his palace there. In the hill of Areopagus, where sat that famous tribunal, we may still discover the steps cut in the rock by which it was ascended, the seats of the judges, and opposite to them those of the accuser and accused. This hill was converted into a burial-place for the Turks, and is covered with their tombs.

Ancient of days! august Athena! where,Where are thy men of might—thy grand in soul?Gone, glimmering through the dream of things that were—First in the race that led to Glory's goal;They won, and passed away. Is this the whole?A schoolboy's tale, the wonder of an hour!The warrior's weapon and the sophist's stoleAre sought in vain, and o'er each mouldering tower,Dim with the mist of years, gray flits the shade of power.Here let me sit, upon this massy stone,The marble column's yet unshaken base;Here, son of Saturn, was thy fav'rite throne—Mightiest of many such! Hence let me traceThe latent grandeur of thy dwelling-place.It may not be—nor ev'n can Fancy's eyeRestore what time hath labour'd to deface:Yet these proud pillars, claiming sigh,Unmoved the Moslem sits—the light Greek carols by.Byron.

THE ISLES OF GREECE

The Isles of Greece! the Isles of Greece!Where burning Sappho loved and sung—Where grew the arts of war and peace,Where Delos rose and Phoebus sprung!Eternal summer gilds them yet,But all except their sun is set.The Scian and the Teian muse,The hero's harp, the lover's lute,Have found the fame your shores refuse;Their place of birth alone is mute,To sounds which echo further westThan your sires' "Islands of the Blest."The mountains look on Marathon—And Marathon looks on the sea;And musing there an hour alone,I dream'd that Greece might still be free;For standing on the Persian's grave,I could not deem myself a slave.A King sat on the rocky brow,Which looks o'er sea-born Salamis;And ships by thousands lay below,And men in nations—all were his!He counted them at break of day—And when the sun set, where were they?And where were they? and where art thou,My country? On thy voiceless shoreThe heroic lay is tuneless now—The heroic bosom beats no more!And must thy lyre, so long divine,Degenerate into hands like mine?'Tis something, in the dearth of fame,Though link'd among a fetter'd race,To feel at least a patriot's shame,Even as I sing, suffuse my face;For what is left the poet here?For Greeks a blush—for Greece a tear.Must we but weep o'er days more blest?Must we but blush?—Our fathers bledEarth! render back from out thy breastA remnant of our Spartan dead!Of the three hundred grant but three,To make a new Thermopylae!What! silent still? and silent all?Ah! no!–the voices of the deadSound like a distant torrent's fall,And answer, "Let one living head—But one—arise! we come, we come!"'Tis but the living who are dumb.In vain—in vain: strike other chords;Fill high the cup with Samian wine!Leave battles to the Turkish hordes,And shed the blood of Scio's vine!Hark! rising to the ignoble call—How answers each bold Bacchanal?You have the Pyrrhic dance as yet;Where is the Pyrrhic phalanx gone?Of two such lessons, why forgetThe nobler and the manlier one?You have the letters Cadmus gave—Think ye he meant them for a slave?Fill high the bowl with Samian wine!We will not think of themes like these!It made Anacreon's song divine;He served—but served Polycrates—A tyrant: but our masters thenWere still at least our countrymen.The tyrant of the ChersoneseWas freedom's best and bravest friend—That tyrant was Miltiades!Oh! that the present hour would lendAnother despot of the kind!Such chains as his were sure to bind.Fill high the bowl with Samian wine!On Suli's rock and Perga's shoreExists the remnant of a lineSuch as the Doric mothers bore;And there, perhaps, some seed is sown,The Heracleidian blood might own.Trust not for freedom to the Franks—They have a King who buys and sells;In native swords and native ranks,The only hope of courage dwells:But Turkish force and Latin fraudWould break your shield, however broad.Fill high the bowl with Samian wine!Our virgins dance beneath the shade—I see their glorious black eyes shine;But gazing on each glowing maid,My own the burning tear drop laves,To think such breasts must suckle slaves!Place me on Sunium's marble steep,Where nothing, save the waves and I,May hear our mutual murmurs sweep;There swan-like let me sing and die:A land of slaves shall ne'er be mine—Dash down yon cup of Samian wine!Byron.

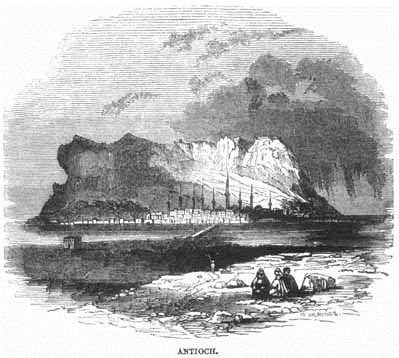

THE SIEGE OF ANTIOCH

Baghasihan, the Turkish Prince, or Emir of Antioch, had under his command an Armenian of the name of Phirouz, whom he had entrusted with the defence of a tower on that part of the city wall which overlooked the passes of the mountains. Bohemund, by means of a spy, who had embraced the Christian religion, and to whom he had given his own name at baptism, kept up a daily communication with this captain, and made him the most magnificent promises of reward if he would deliver up his post to the Crusaders. Whether the proposal was first made by Bohemund or by the Armenian, is uncertain, but that a good understanding soon existed between them is undoubted; and a night was fixed for the execution of the project. Bohemund communicated the scheme to Godfrey and the Count of Toulouse, with the stipulation that, if the city were won, he, as the soul of the enterprise, should enjoy the dignity of Prince of Antioch. The other leaders hesitated: ambition and jealousy prompted them to refuse their aid in furthering the views of the intriguer. More mature consideration decided them to acquiesce, and seven hundred of the bravest knights were chosen for the expedition, the real object of which, for fear of spies, was kept a profound secret from the rest of the army.

Everything favoured the treacherous project of the Armenian captain, who, on his solitary watch-tower, received due intimation of the approach of the Crusaders. The night was dark and stormy: not a star was visible above; and the wind howled so furiously as to overpower all other sounds. The rain fell in torrents, and the watchers on the towers adjoining to that of Phirouz could not hear the tramp of the armed knights for the wind, nor see them for the obscurity of the night and the dismalness of the weather. When within bow-shot of the walls, Bohemund sent forward an interpreter to confer with the Armenian. The latter urged them to make haste and seize the favourable interval, as armed men, with lighted torches, patrolled the battlements every half-hour, and at that instant they had just passed. The chiefs were instantly at the foot of the wall. Phirouz let down a rope; Bohemund attached to it a ladder of hides, which was then raised by the Armenian, and held while the knights mounted. A momentary fear came over the spirits of the adventurers, and every one hesitated; at last Bohemund, encouraged by Phirouz from above, ascended a few steps on the ladder, and was followed by Godfrey, Count Robert of Flanders, and a number of other knights. As they advanced, others pressed forward, until their weight became too great for the ladder, which, breaking, precipitated about a dozen of them to the ground, where they fell one upon the other, making a great clatter with their heavy coats of mail. For a moment they thought all was lost; but the wind made so loud a howling, as it swept in fierce gusts through the mountain gorges, and the Orontes, swollen by the rain, rushed so noisily along, that the guards heard nothing. The ladder was easily repaired, and the knights ascended, two at a time, and reached the platform in safety. When sixty of them had thus ascended, the torch of the coming patrol was seen to gleam at the angle of the wall. Hiding themselves behind a buttress, they awaited his coming in breathless silence. As soon as he arrived at arm's length, he was suddenly seized; and before he could open his lips to raise an alarm, the silence of death closed them up for ever. They next descended rapidly the spiral staircase of the tower, and, opening the portal, admitted the whole of their companions. Raymond of Toulouse, who, cognizant of the whole plan, had been left behind with the main body of the army, heard at this instant the signal horn, which announced that an entry had been effected, and advancing with his legions, the town was attacked from within and from without.

Imagination cannot conceive a scene more dreadful than that presented by the devoted city of Antioch on that night of horror. The Crusaders fought with a blind fury, which fanaticism and suffering alike incited. Men, women, and children were indiscriminately slaughtered, till the streets ran in gore. Darkness increased the destruction; for, when the morning dawned the Crusaders found themselves with their swords at the breasts of their fellow-soldiers, whom they had mistaken to be foes. The Turkish commander fled, first to the citadel, and, that becoming insecure, to the mountains, whither he was pursued and slain, and his gory head brought back to Antioch as a trophy. At daylight the massacre ceased, and the Crusaders gave themselves up to plunder.

Popular Delusions.ANGLING

Go, take thine angle, and with practised line,Light as the gossamer, the current sweep;And if thou failest in the calm, still deep,In the rough eddy may a prize be thine.Say thou'rt unlucky where the sunbeams shine;Beneath the shadow where the waters creepPerchance the monarch of the brook shall leap—For Fate is ever better than Design.Still persevere; the giddiest breeze that blowsFor thee may blow with fame and fortune rife.Be prosperous; and what reck if it aroseOut of some pebble with the stream at strife,Or that the light wind dallied with the boughs:Thou art successful—such is human life.Doubleday.MARIANA

Mariana in the moated grange.—Measure for Measure

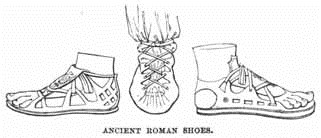

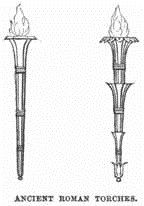

RISE OF POETRY AMONG THE ROMANS

The Romans, in the infancy of their state, were entirely rude and unpolished. They came from shepherds; they were increased from the refuse of the nations around them; and their manners agreed with their original. As they lived wholly on tilling their ground at home, or on plunder from their neighbours, war was their business, and agriculture the chief art they followed. Long after this, when they had spread their conquests over a great part of Italy, and began to make a considerable figure in the world—even their great men retained a roughness, which they raised into a virtue, by calling it Roman spirit; and which might often much better have been called Roman barbarity. It seems to me, that there was more of austerity than justice, and more of insolence than courage, in some of their most celebrated actions. However that be, this is certain, that they were at first a nation of soldiers and husbandmen: roughness was long an applauded character among them; and a sort of rusticity reigned, even in their senate-house.

In a nation originally of such a temper as this, taken up almost always in extending their territories, very often in settling the balance of power among themselves, and not unfrequently in both these at the same time, it was long before the politer arts made any appearance; and very long before they took root or flourished to any degree. Poetry was the first that did so; but such a poetry as one might expect among a warlike, busied, unpolished people.

Not to enquire about the songs of triumph mentioned even in Romulus's time, there was certainly something of poetry among them in the next reign, under Numa; a Prince who pretended to converse with the Muses as well as with Egeria, and who might possibly himself have made the verses which the Salian priests sang in his time. Pythagoras, either in the same reign, or if you please some time after, gave the Romans a tincture of poetry as well as of philosophy; for Cicero assures us that the Pythagoreans made great use of poetry and music; and probably they, like our old Druids, delivered most of their precepts in verse. Indeed, the chief employment of poetry in that and the following ages, among the Romans, was of a religious kind. Their very prayers, and perhaps their whole liturgy, was poetical. They had also a sort of prophetic or sacred writers, who seem to have written generally in verse; and were so numerous that there were above two thousand of their volumes remaining even to Augustus's time. They had a kind of plays too, in these early times, derived from what they had seen of the Tuscan actors when sent for to Rome to expiate a plague that raged in the city. These seem to have been either like our dumb-shows, or else a kind of extempore farces—a thing to this day a good deal in use all over Italy and in Tuscany. In a more particular manner, add to these that extempore kind of jesting dialogues begun at their harvest and vintage feasts, and carried on so rudely and abusively afterwards as to occasion a very severe law to restrain their licentiousness; and those lovers of poetry and good eating, who seem to have attended the tables of the richer sort, much like the old provincial poets, or our own British bards, and sang there to some instrument of music the achievements of their ancestors, and the noble deeds of those who had gone before them, to inflame others to follow their great examples.

The names of almost all these poets sleep in peace with all their works; and, if we may take the word of the other Roman writers of a better age, it is no great loss to us. One of their best poets represents them as very obscure and very contemptible; one of their best historians avoids quoting them as too barbarous for politer ears; and one of their most judicious emperors ordered the greatest part of their writings to be burnt, that the world might be troubled with them no longer.

All these poets, therefore, may very well be dropped in the account, there being nothing remaining of their works, and probably no merit to be found in them if they had remained. And so we may date the beginning of the Roman poetry from Livius Andronicus, the first of their poets of whom anything does remain to us; and from whom the Romans themselves seem to have dated the beginning of their poetry, even in the Augustan age.

The first kind of poetry that was followed with any success among the Romans, was that for the stage. They were a very religious people; and stage plays in those times made no inconsiderable part in their public devotions; it is hence, perhaps, that the greatest number of their oldest poets, of whom we have any remains, and, indeed, almost all of them, are dramatic poets.

Spence.CHARACTER OF JULIUS CAESAR

Caesar was endowed with every great and noble quality that could exalt human nature, and give a man the ascendant in society. Formed to excel in peace as well as war; provident in council; fearless in action, and executing what he had resolved with an amazing celerity; generous beyond measure to his friends; placable to his enemies; and for parts, learning, and eloquence, scarce inferior to any man. His orations were admired for two qualities, which are seldom found together, strength and elegance: Cicero ranks him among the greatest orators that Rome ever bred; and Quintilian says, that he spoke with the same force with which he fought; and if he had devoted himself to the bar, would have been the only man capable of rivalling Cicero. Nor was he a master only of the politer arts; but conversant also with the most abstruse and critical parts of learning; and, among other works which he published, addressed two books to Cicero on the analogy of language, or the art of speaking and writing correctly. He was a most liberal patron of wit and learning, wheresoever they were found; and out of his love of those talents, would readily pardon those who had employed them against himself; rightly judging, that by making such men his friends, he should draw praises from the same fountain from which he had been aspersed. His capital passions were ambition and love of pleasure, which he indulged in their turns to the greatest excess; yet the first was always predominant—to which he could easily sacrifice all the charms of the second, and draw pleasure even from toils and dangers, when they ministered to his glory. For he thought Tyranny, as Cicero says, the greatest of goddesses; and had frequently in his mouth a verse of Euripides, which expressed the image of his soul, that if right and justice were ever to be violated, they were to be violated for the sake of reigning. This was the chief end and purpose of his life—the scheme that he had formed from his early youth; so that, as Cato truly declared of him, he came with sobriety and meditation to the subversion of the republic. He used to say, that there were two things necessary to acquire and to support power—soldiers and money; which yet depended mutually upon each other: with money, therefore, he provided soldiers, and with soldiers extorted money, and was, of all men, the most rapacious in plundering both friends and foes; sparing neither prince, nor state, nor temple, nor even private persons who were known to possess any share of treasure. His great abilities would necessarily have made him one of the first citizens of Rome; but, disdaining the condition of a subject, he could never rest till he made himself a Monarch. In acting this last part, his usual prudence seemed to fail him; as if the height to which he was mounted had turned his head and made him giddy; for, by a vain ostentation of his power, he destroyed the stability of it; and, as men shorten life by living too fast, so by an intemperance of reigning he brought his reign to a violent end.