полная версия

полная версияThe Illustrated London Reading Book

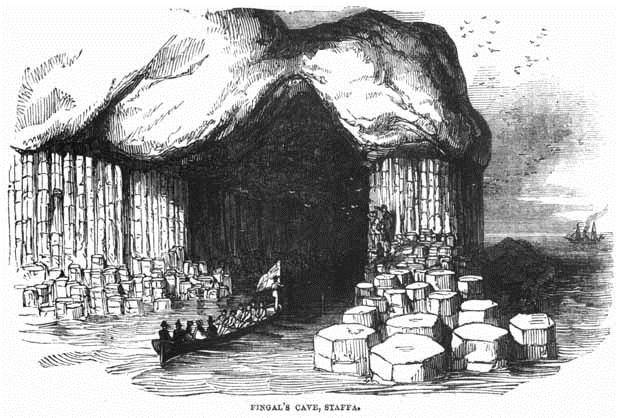

The complete stillness of the scene, except the low plashing of the waves; the fitful gleams of light thrown first on the walls and ceiling, as the men moved to and fro along the side of the stupendous cave; the appearance of the varied roof, where different stalactites or petrifactions are visible; the vastness and perfect art or semblance of art of the whole, altogether formed a scene the most sublime, grand, and impressive ever witnessed.

The Cathedral of Iona sank into insignificance before this great temple of nature, reared, as if in mockery of the temples of man, by the Almighty Power who laid the beams of his chambers on the waters, and who walketh upon the wings of the wind. Macculloch says that it is with the morning sun only that the great face of Staffa can be seen in perfection; as the general surface is undulating and uneven, large masses of light or shadow are thus produced. We can believe, also, that the interior of the cave, with its broken pillars and variety of tints, and with the green sea rolling over a dark red or violet-coloured rock, must be seen to more advantage in the full light of day. Yet we question whether we could have been more deeply sensible of the beauty and grandeur of the scene than we were under the unusual circumstances we have described. The boatmen sang a Gaelic joram or boat-song in the cave, striking their oars very violently in time with the music, which resounded finely through the vault, and was echoed back by roof and pillar. One of them, also, fired a gun, with the view of producing a still stronger effect of the same kind. When we had fairly satisfied ourselves with contemplating the cave, we all entered the boat and sailed round by the Clamshell Cave (where the basaltic columns are bent like the ribs of a ship), and the Rock of the Bouchaille, or the herdsman, formed of small columns, as regular and as interesting as the larger productions. We all clambered to the top of the rock, which affords grazing for sheep and cattle, and is said to yield a rent of £20 per annum to the proprietor. Nothing but the wide surface of the ocean was visible from our mountain eminence, and after a few minutes' survey we descended, returned to the boat, and after regaining the steam-vessel, took our farewell look of Staffa, and steered on for Tobermory.

Highland Note-Book.

ON CHEERFULNESS

I have always preferred cheerfulness to mirth. The latter I consider as an act, the former as a habit of the mind. Mirth is short and transient, cheerfulness fixed and permanent. Those are often raised into the greatest transports of mirth, who are subject to the greatest depressions of melancholy: on the contrary, cheerfulness, though it does not give the mind such an exquisite gladness, prevents us from falling into any depths of sorrow. Mirth is like a flash of lightning, that breaks through a gloom of clouds, and glitters for a moment; cheerfulness keeps up a kind of daylight in the mind, and fills it with a steady and perpetual serenity.

Men of austere principles look upon mirth as too wanton and dissolute for a state of probation, and as filled with a certain triumph and insolence of heart that is inconsistent with a life which is every moment obnoxious to the greatest dangers. Writers of this complexion have observed, that the sacred Person who was the great pattern of perfection, was never seen to laugh.

Cheerfulness of mind is not liable to any of these exceptions; it is of a serious and composed nature; it does not throw the mind into a condition improper for the present state of humanity, and is very conspicuous in the characters of those who are looked upon as the greatest philosophers among the heathen, as well as among those who have been deservedly esteemed as saints and holy men among Christians.

If we consider cheerfulness in three lights, with regard to ourselves, to those we converse with, and the great Author of our being, it will not a little recommend itself on each of these accounts. The man who is possessed of this excellent frame of mind, is not only easy in his thoughts, but a perfect master of all the powers and faculties of the soul; his imagination is always clear, and his judgment undisturbed; his temper is even and unruffled, whether in action or solitude. He comes with a relish to all those goods which nature has provided for him, tastes all the pleasures of the creation which are poured about him, and does not feel the full weight of those accidental evils which may befall him.

If we consider him in relation to the persons whom he converses with, it naturally produces love and good-will towards him. A cheerful mind is not only disposed to be affable and obliging, but raises the same good-humour in those who come within its influence. A man finds himself pleased, he does not know why, with the cheerfulness of his companion: it is like a sudden sunshine, that awakens a secret delight in the mind, without her attending to it. The heart rejoices of its own accord, and naturally flows out into friendship and benevolence towards the person who has so kindly an effect upon it.

When I consider this cheerful state of mind in its third relation, I cannot but look upon it as a constant, habitual gratitude to the great Author of nature.

There are but two things which, in my opinion, can reasonably deprive us of this cheerfulness of heart. The first of these is the sense of guilt. A man who lives in a state of vice and impenitence, can have no title to that evenness and tranquillity of mind which is the health of the soul, and the natural effect of virtue and innocence. Cheerfulness in an ill man deserves a harder name than language can furnish us with, and is many degrees beyond what we commonly call folly or madness.

Atheism, by which I mean a disbelief of a Supreme Being, and consequently of a future state, under whatsoever title it shelters itself, may likewise very reasonably deprive a man of this cheerfulness of temper. There is something so particularly gloomy and offensive to human nature in the prospect of non-existence, that I cannot but wonder, with many excellent writers, how it is possible for a man to outlive the expectation of it. For my own part, I think the being of a God is so little to be doubted, that it is almost the only truth we are sure of, and such a truth as we meet with in every object, in every occurrence, and in every thought. If we look into the characters of this tribe of infidels, we generally find they are made up of pride, spleen, and cavil: it is indeed no wonder that men who are uneasy to themselves, should be so to the rest of the world; and how is it possible for a man to be otherwise than uneasy in himself, who is in danger every moment of losing his entire existence and dropping into nothing?

The vicious man and Atheist have therefore no pretence to cheerfulness, and would act very unreasonably should they endeavour after it. It is impossible for any one to live in good-humour and enjoy his present existence, who is apprehensive either of torment or of annihilation—of being miserable or of not being at all.

After having mentioned these two great principles, which are destructive of cheerfulness in their own nature, as well as in right reason, I cannot think of any other that ought to banish this happy temper from a virtuous mind. Pain and sickness, shame and reproach, poverty and old age; nay, death itself, considering the shortness of their duration and the advantage we may reap from them, do not deserve the name of evils. A good mind may bear up under them with fortitude, with indolence, and with cheerfulness of heart. The tossing of a tempest does not discompose him, which he is sure will bring him to a joyful harbour.

A man who uses his best endeavours to live according to the dictates of virtue and right reason, has two perpetual sources of cheerfulness, in the consideration of his own nature and of that Being on whom he has a dependence. If he looks into himself, he cannot but rejoice in that existence which is so lately bestowed upon him, and which, after millions of ages, will be still new and still in its beginning. How many self-congratulations naturally arise in the mind when it reflects on this its entrance into eternity, when it takes a view of those improvable faculties which in a few years, and even at its first setting out, have made so considerable a progress, and which will be still receiving an increase of perfection, and consequently an increase of happiness! The consciousness of such a being spreads a perpetual diffusion of joy through the soul of a virtuous man, and makes him look upon himself every moment as more happy than he knows how to conceive.

The second source of cheerfulness to a good mind is its consideration of that Being on whom we have our dependence, and in whom, though we behold Him as yet but in the first faint discoveries of his perfections, we see every thing that we can imagine as great, glorious, and amiable. We find ourselves every where upheld by his goodness and surrounded with an immensity of love and mercy. In short, we depend upon a Being whose power qualifies Him to make us happy by an infinity of means, whose goodness and truth engage Him to make those happy who desire it of Him, and whose unchangeableness will secure us in this happiness to all eternity.

Such considerations, which every one should perpetually cherish in his thoughts, will banish from us all that secret heaviness of heart which unthinking men are subject to when they lie under no real affliction, all that anguish which we may feel from any evil that actually oppresses us, to which I may likewise add those little cracklings of mirth and folly, that are apter to betray virtue than support it; and establish in us such an even and cheerful temper, as makes us pleasing to ourselves, to those with whom we converse, and to Him whom we are made to please.

Addison.STONY CROSS

This is the place where King William Rufus was accidentally shot by Sir Walter Tyrrel. There has been much controversy on the details of this catastrophe; but the following conclusions, given in the "Pictorial History of England," appear to be just:—"That the King was shot by an arrow in the New Forest; that his body was abandoned and then hastily interred, are facts perfectly well authenticated; but some doubts may be entertained as to the precise circumstances attending his death, notwithstanding their being minutely related by writers who were living at the time, or who flourished in the course of the following century. Sir Walter Tyrrel afterwards swore, in France, that he did not shoot the arrow; but he was, probably, anxious to relieve himself from the odium of killing a King, even by accident. It is quite possible, indeed, that the event did not arise from chance, and that Tyrrel had no part in it. The remorseless ambition of Henry might have had recourse to murder, or the avenging shaft might have been sped by the desperate hand of some Englishman, tempted by a favourable opportunity and the traditions of the place. But the most charitable construction is, that the party were intoxicated with the wine they had drunk at Malwood-Keep, and that, in the confusion consequent on drunkenness, the King was hit by a random arrow."

In that part of the Forest near Stony Cross, at a short distance from Castle Malwood, formerly stood an oak, which tradition affirmed was the tree against which the arrow glanced that caused the death of Rufus. Charles II. directed the tree to be encircled by a paling: it has disappeared; but the spot whereon the tree grew is marked by a triangular stone, about five feet high, erected by Lord Delaware, upwards of a century ago. The stone has since been faced with an iron casting of the following inscription upon the three sides:—

"Here stood the oak-tree on which an arrow, shot by Sir Walter Tyrrel at a stag, glanced and struck King William II., surnamed Rufus, on the breast; of which stroke he instantly died, on the 2nd of August, 1100.

"King William II., surnamed Rufus, being slain, as before related, was laid in a cart belonging to one Purkess, and drawn from hence to Winchester, and buried in the cathedral church of that city.

" That where an event so memorable had happened might not hereafter be unknown, this stone was set up by John Lord Delaware, who had seen the tree growing in this place, anno 1745."

Stony Cross is a favourite spot for pic-nic parties in the summer. It lies seven miles from Ringwood, on a wide slope among the woods. From the road above, splendid views over the country present themselves.

GELERT

The spearman heard the bugle sound,And cheerily smiled the morn;And many a brach, and many a hound,Attend Llewellyn's horn.And still he blew a louder blast,And gave a louder cheer:"Come, Gelert! why art thou the lastLlewellyn's horn to hear?"Oh, where does faithful Gelert roam—The flower of all his race!So true, so brave—a lamb at home,A lion in the chase?"That day Llewellyn little lovedThe chase of hart or hare;And scant and small the booty proved,For Gelert was not there.Unpleased Llewellyn homeward hied,When, near the portal-seat,His truant Gelert he espied,Bounding his lord to greet.But when he gained the castle-door,Aghast the chieftain stood;The hound was smear'd with gouts of gore—His lips and fangs ran blood!Llewellyn gazed with wild surprise,Unused such looks to meet;His favourite check'd his joyful guise,And crouch'd and lick'd his feet.Onward in haste Llewellyn pass'd(And on went Gelert too),And still where'er his eyes were cast,Fresh blood-gouts shock'd his view!O'erturn'd his infant's bed he found,The blood-stain'd cover rent,And all around the walls and groundWith recent blood besprent.He call'd his child—no voice replied;He search'd—with terror wild;Blood! blood! he found on every side,But nowhere found the child!"Hell-hound! by thee my child's devour'd!"The frantic father cried,And to the hilt his vengeful swordHe plunged in Gelert's side!His suppliant, as to earth he fell,No pity could impart;But still his Gelert's dying yellPass'd heavy o'er his heart.Aroused by Gelert's dying yell,Some slumberer waken'd nigh:What words the parent's joy can tell,To hear his infant cry!Conceal'd beneath a mangled heap,His hurried search had miss'd:All glowing from his rosy sleep,His cherub boy he kiss'd!Nor scratch had he, nor harm, nor dread;But the same couch beneathLay a great wolf, all torn and dead—Tremendous still in death!Ah! what was then Llewellyn's pain,For now the truth was clear;The gallant hound the wolf had slainTo save Llewellyn's heir.Vain, vain was all Llewellyn's woe—"Best of thy kind, adieu!The frantic deed which laid thee low,This heart shall ever rue!"And now a gallant tomb they raise,With costly sculpture deck'd;And marbles, storied with his praise,Poor Gelert's bones protect.Here never could the spearman pass,Or forester, unmoved;Here oft the tear-besprinkled grassLlewellyn's sorrow proved.And here he hung his horn and spear;And oft, as evening fell,In fancy's piercing sounds would hearPoor Gelert's dying yell.W. Spencer.

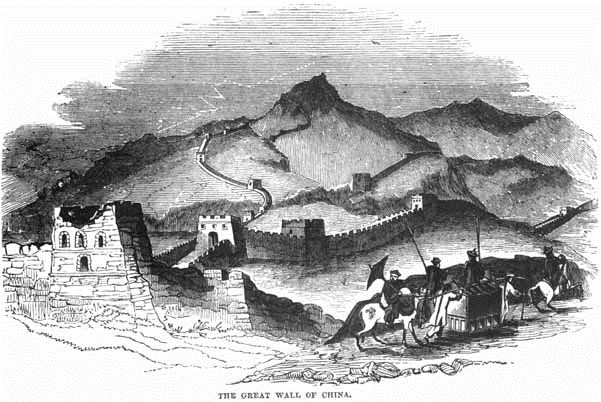

THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA

The important feature which the Great Wall makes in the map of China, entitles this vast barrier to be considered in a geographical point of view, as it bounds the whole north of China along the frontiers of three provinces. It was built by the first universal Monarch of China, and finished about 205 years before Christ: the period of its completion is an historical fact, as authentic as any of those which the annals of ancient kingdoms have transmitted to posterity. It was built to defend the Chinese Empire from the incursions of the Tartars, and is calculated to be 1500 miles in length. The rapidity with which this work was completed is as astonishing as the wall itself, for it is said to have been done in five years, by many millions of labourers, the Emperor pressing three men out of every ten, in his dominions, for its execution. For about the distance of 200 leagues, it is generally built of stone and brick, with strong square towers, sufficiently near for mutual defence, and having besides, at every important pass, a formidable and well-built fortress. In many places, in this line and extent, the wall is double, and even triple; but from the province of Can-sih to its eastern extremity, it is nothing but a terrace of earth, of which the towers on it are also constructed. The Great Wall, which has now, even in its best parts, numerous breaches, is made of two walls of brick and masonry, not above a foot and a half in thickness, and generally many feet apart; the interval between them is filled up with earth, making the whole appear like solid masonry and brickwork. For six or seven feet from the earth, these are built of large square stones; the rest is of blue brick, the mortar used in which is of excellent quality. The wall itself averages about 20 feet in height, 25 feet in thickness at the base, which diminishes to 15 feet at the platform, where there is a parapet wall; the top is gained by stairs and inclined planes. The towers are generally about 40 feet square at the base, diminishing to 30 feet a the top, and are, including battlements, 37 feet in height. At some spots the towers consist of two stories, and are thus much higher. The wall is in many places carried over the tops of the highest and most rugged rocks; and one of these elevated regions is 5000 feet above the level of the sea.

Near each of the gates is a village or town; and at one of the principal gates, which opens on the road towards India, is situated Sinning-fu, a city of large extent and population. Here the wall is said to be sufficiently broad at the top to admit six horsemen abreast, who might without inconvenience ride a race. The esplanade on its top is much frequented by the inhabitants, and the stairs which give ascent are very broad and convenient.

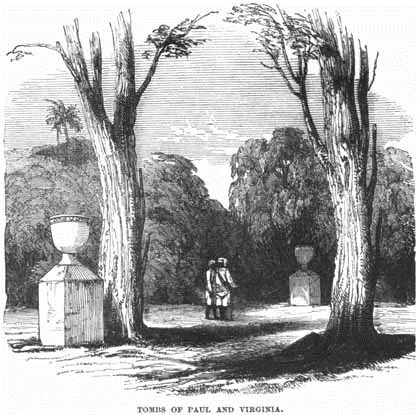

THE TOMBS OF PAUL AND VIRGINIA

This delicious retreat in the island of Mauritius has no claims to the celebrity it has attained. It is not the burial-place of Paul and Virginia; and the author of "Recollections of the Mauritius" thus endeavours to dispel the illusion connected with the spot:—

"After having allowed his imagination to depict the shades of Paul and Virginia hovering about the spot where their remains repose—after having pleased himself with the idea that he had seen those celebrated tombs, and given a sigh to the memory of those faithful lovers, separated in life, but in death united—after all this waste of sympathy, he learns at last that he has been under a delusion the whole time—that no Virginia was there interred—and that it is a matter of doubt whether there ever existed such a person as Paul! What a pleasing illusion is then dispelled! How many romantic dreams, inspired by the perusal of St. Pierre's tale, are doomed to vanish when the truth is ascertained! The fact is, that these tombs have been built to gratify the eager desire which the English have always evinced to behold such interesting mementoes. Formerly only one was erected; but the proprietor of the place, finding that all the English visitors, on being conducted to this, as the tomb of Virginia, always asked to see that of Paul also, determined on building a similar one, to which he gave that appellation. Many have been the visitors who have been gratified, consequently, by the conviction that they had looked on the actual burial-place of that unfortunate pair. These 'tombs' are scribbled over with the names of the various persons who have visited them, together with verses and pathetic ejaculations and sentimental remarks. St. Pierre's story of the lovers is very prettily written, and his description of the scenic beauties of the island are correct, although not even his pen can do full justice to them; but there is little truth in the tale. It is said that there was indeed a young lady sent from the Mauritius to France for education, during the time that Monsieur de la Bourdonnais was governor of the colony—that her name was Virginia, and that she was shipwrecked in the St. Geran. I heard something of a young man being attached to her, and dying of grief for her loss; but that part of the story is very doubtful. The 'Bay of the Tomb,' the 'Point of Endeavour,' the 'Isle of Amber,' and the 'Cape of Misfortune,' still bear the same names, and are pointed out as the memorable spots mentioned by St. Pierre."

THE MANGOUSTE

The Mangoustes, or Ichneumons, are natives of the hotter parts of the Old World, the species being respectively African and Indian. In their general form and habits they bear a great resemblance to the ferrets, being bold, active, and sanguinary, and unrelenting destroyers of birds, reptiles, and small animals, which they take by surprise, darting rapidly upon them. Beautiful, cleanly, and easily domesticated, they are often kept tame in the countries they naturally inhabit, for the purpose of clearing the houses of vermin, though the poultry-yard is not safe from their incursions.

The Egyptian mangouste is a native of North Africa, and was deified for its services by the ancient Egyptians. Snakes, lizards, birds, crocodiles newly hatched, and especially the eggs of crocodiles, constitute its food. It is a fierce and daring animal, and glides with sparkling eyes towards its prey, which it follows with snake-like progression; often it watches patiently for hours together, in one spot, waiting the appearance of a mouse, rat, or snake, from its lurking-place. In a state of domestication it is gentle and affectionate, and never wanders from the house or returns to an independent existence; but it makes itself familiar with every part of the premises, exploring every hole and corner, inquisitively peeping into boxes and vessels of all kinds, and watching every movement or operation.

The Indian mangouste is much less than the Egyptian, and of a beautiful freckled gray. It is not more remarkable for its graceful form and action, than for the display of its singular instinct for hunting for and stealing eggs, from which it takes the name of egg-breaker. Mr. Bennett, in his account of one of the mangoustes kept in the Tower, says, that on one occasion it killed no fewer than a dozen full-grown rats, which were loosened to it in a room sixteen feet square, in less than a minute and a half.

Another species of the mangouste, found in the island of Java, inhabiting the large teak forests, is greatly admired by the natives for its agility. It attacks and kills serpents with excessive boldness. It is very expert in burrowing in the ground, which process it employs ingeniously in the pursuit of rats. It possesses great natural sagacity, and, from the peculiarities of its character, it willingly seeks the protection of man. It is easily tamed, and in its domestic state is very docile and attached to its master, whom it follows like a dog; it is fond of caresses, and frequently places itself erect on its hind legs, regarding every thing that passes with great attention. It is of a very restless disposition, and always carries its food to the most retired place to consume it, and is very cleanly in its habits; but it is exclusively carnivorous and destructive to poultry, employing great artifice in surprising chickens.