полная версия

полная версияThe Illustrated London Reading Book

Various

The Illustrated London Reading Book

INTRODUCTION

To read and speak with elegance and ease,Are arts polite that never fail to please;Yet in those arts how very few excel!Ten thousand men may read—not one read well.Though all mankind are speakers in a sense,How few can soar to heights of eloquence!The sweet melodious singer trills her lays,And listening crowds go frantic in her praise;But he who reads or speaks with feeling true,Charms and delights, instructs, and moves us too.Browne.To deprive Instruction of the terrors with which the young but too often regard it, and strew flowers upon the pathways that lead to Knowledge, is to confer a benefit upon all who are interested in the cause of Education, either as Teachers or Pupils. The design of the following pages is not merely to present to the youthful reader some of the masterpieces of English literature in prose and verse, arranged and selected in such a manner as to please as well as instruct, but to render them more agreeable to the eye and the imagination by Pictorial Representations, in illustration of the subjects. It is hoped that this design has not been altogether unsuccessful, and that the ILLUSTRATED LONDON READING BOOK will recommend itself both to old and young by the appropriateness of the selections, their progressive arrangement, the fidelity of their Illustrations, and the very moderate price at which it is offered to the public.

It has not been thought necessary to prefix to the present Volume any instructions in the art of Elocution, or to direct the accent or intonation of the student by the abundant use of italics or of large capitals. The principal, if not the only secrets of good reading are, to speak slowly, to articulate distinctly, to pause judiciously, and to feel the subject so as, if possible, "to make all that passed in the mind of the Author to be felt by the Auditor," Good oral example upon these points is far better for the young Student than the most elaborate written system.

A series of Educational Works, in other departments of study, similarly illustrated, and at a price equally small, is in preparation. Among the earliest to be issued, may be enumerated a Sequel and Companion to the ILLUSTRATED LONDON READING BOOK, designed for a more advanced class of Students, and consisting of extracts from English Classical Authors, from the earliest periods of English Literature to the present day, with a copious Introductory Chapter upon the arts of Elocution and Composition. The latter will include examples of Style chosen from the beauties of the best Authors, and will also point out by similar examples the Faults to be avoided by all who desire to become, not simply good Readers and Speakers, but elegant Writers of their native language.

Amongst the other works of which the series will be composed, may be mentioned, profusely Illustrated Volumes upon Geographical, Astronomical, Mathematical, and General Science, as well as works essential to the proper training of the youthful mind.

January, 1850.

THE SCHOOLBOY'S PILGRIMAGE

Nothing could be more easy and agreeable than my condition when I was first summoned to set out on the road to learning, and it was not without letting fall a few ominous tears that I took the first step. Several companions of my own age accompanied me in the outset, and we travelled pleasantly together a good part of the way.

We had no sooner entered upon our path, than we were accosted by three diminutive strangers. These we presently discovered to be the advance-guard of a Lilliputian army, which was seen advancing towards us in battle array. Their forms were singularly grotesque: some were striding across the path, others standing with their arms a-kimbo; some hanging down their heads, others quite erect; some standing on one leg, others on two; and one, strange to say, on three; another had his arms crossed, and one was remarkably crooked; some were very slender, and others as broad as they were long. But, notwithstanding this diversity of figure, when they were all marshalled in line of battle, they had a very orderly and regular appearance. Feeling disconcerted by their numbers, we were presently for sounding a retreat; but, being urged forward by our guide, we soon mastered the three who led the van, and this gave us spirit to encounter the main army, who were conquered to a man before we left the field. We had scarcely taken breath after this victory, when, to our no small dismay, we descried a strong reinforcement of the enemy, stationed on the opposite side. These were exactly equal in number to the former army, but vastly superior in size and stature; they were, in fact, a race of giants, though of the same species with the others, and were capitally accoutred for the onset. Their appearance discouraged us greatly at first, but we found their strength was not proportioned to their size; and, having acquired much skill and courage by the late engagement, we soon succeeded in subduing them, and passed off the field in triumph. After this we were perpetually engaged with small bands of the enemy, no longer extended in line of battle, but in small detachments of two, three, and four in company. We had some tough work here, and now and then they were too many for us. Having annoyed us thus for a time, they began to form themselves into close columns, six or eight abreast; but we had now attained so much address, that we no longer found them formidable.

After continuing this route for a considerable way, the face of the country suddenly changed, and we began to enter upon a vast succession of snowy plains, where we were each furnished with a certain light weapon, peculiar to the country, which we flourished continually, and with which we made many light strokes, and some desperate ones. The waters hereabouts were dark and brackish, and the snowy surface of the plain was often defaced by them. Probably, we were now on the borders of the Black Sea. These plains we travelled across and across for many a day.

Upon quitting this district, the country became far more dreary: it appeared nothing but a dry and sterile region, the soil being remarkably hard and slatey. Here we saw many curious figures, and we soon found that the inhabitants of this desert were mere ciphers. Sometimes they appeared in vast numbers, but only to be again suddenly diminished.

Our road, after this, wound through a rugged and hilly country, which was divided into nine principal parts or districts, each under a different governor; and these again were reduced into endless subdivisions. Some of them we were obliged to decline. It was not a little puzzling to perceive the intricate ramifications of the paths in these parts. Here the natives spoke several dialects, which rendered our intercourse with them very perplexing. However, it must be confessed that every step we set in this country was less fatiguing and more interesting. Our course at first lay all up hill; but when we had proceeded to a certain height, the distant country, which is most richly variegated, opened freely to our view.

I do not mean at present to describe that country, or the different stages by which we advance through its scenery. Suffice it to say, that the journey, though always arduous, has become more and more pleasant every stage; and though, after years of travel and labour, we are still very far from the Temple of Learning, yet we have found on the way more than enough to make us thankful to the kindness of the friends who first set us on the path, and to induce us to go forward courageously and rejoicingly to the end of the journey.

JANE TAYLOR.PEKIN

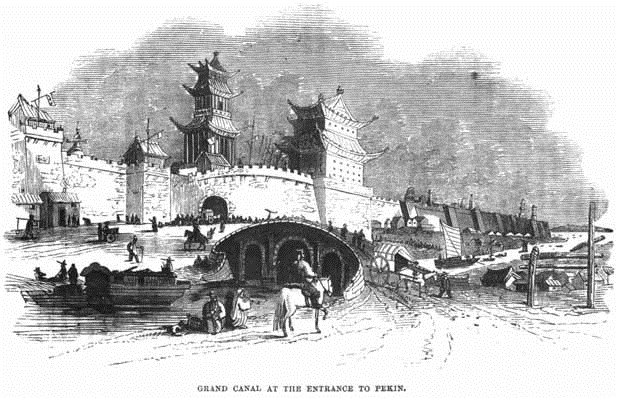

Pekin, or Peking, a word which in Chinese means "Northern Capital," has been the chief city of China ever since the Tartars were expelled, and is the residence of the Emperor. The tract of country on which it stands is sandy and barren; but the Grand Canal is well adapted for the purpose of feeding its vast population with the produce of more fertile provinces and districts. A very large portion of the centre of the part of Pekin called the Northern City is occupied by the Emperor with his palaces and gardens, which are of the most beautiful description, and, surrounded by their own wall, form what is called the "Prohibited City."

The Grand Canal, which runs about five hundred miles, without allowing for windings, across the kingdom of China, is not only the means by which subsistence is brought to the inhabitants of the imperial city, but is of great value in conveying the tribute, a large portion of the revenue being paid in kind. Dr. Davis mentions having observed on it a large junk decorated with a yellow umbrella, and found on enquiry that it had the honour of bearing the "Dragon robes," as the Emperor's garments are called. These are forwarded annually, and are the peculiar tribute of the silk districts. The banks of the Grand Canal are, in many parts through which it flows, strongly faced with stone, a precaution very necessary to prevent the danger of inundations, from which some parts of this country are constantly suffering. The Yellow River so very frequently overflows its banks, and brings so much peril and calamity to the people, that it has been called "China's Sorrow;" and the European trade at Canton has been very heavily taxed for the damage occasioned by it.

The Grand Canal and the Yellow River, in one part of the country, run within four or five miles of each other, for about fifty miles; and at length they join or cross each other, and then run in a contrary direction. A great deal of ceremony is used by the crews of the vessels when they reach this point, and, amongst other customs, they stock themselves abundantly with live cocks, destined to be sacrificed on crossing the river. These birds annoy and trouble the passengers so much by their incessant crowing on the top of the boats, that they are not much pitied when the time for their death arrives. The boatmen collect money for their purchase from the passengers, by sending red paper petitions called pin, begging for aid to provide them with these and other needful supplies. The difficulties which the Chinese must have struggled against, with their defective science, in this junction of the canal and the river, are incalculable; and it is impossible to deny them the praise they deserve for so great an exercise of perseverance and industry.

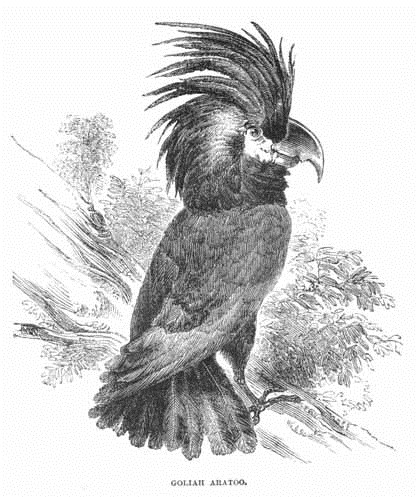

THE GOLIAH ARATOO

The splendid family of parrots includes about one hundred and sixty species, and, though peculiar to the warmer regions of the world, they are better known in England than any other foreign bird. From the beauty of their plumage, the great docility of their manners, and the singular faculty they possess of imitating the human voice, they are general favourites, both in the drawingroom of the wealthy and the cottage of humble life.

The various species differ in size, as well as in appearance and colour. Some (as the macaws) are larger than the domestic fowl, and some of the parakeets are not larger than a blackbird or even a sparrow.

The interesting bird of which our Engraving gives a representation was recently brought alive to this country by the captain of a South-seaman (the Alert), who obtained it from a Chinese vessel from the Island of Papua, to whom the captain of the Alert rendered valuable assistance when in a state of distress. In size this bird is one of the largest of the parrot tribe, being superior to the great red Mexican Macaw. The whole plumage is black, glossed with a greenish grey; the head is ornamented with a large crest of long pendulous feathers, which it erects at pleasure, when the bird has a most noble appearance; the orbits of the eyes and cheeks are of a deep rose-colour; the bill is of great size, and will crack the hardest fruit stones; but when the kernel is detached, the bird does not crush and swallow it in large fragments, but scrapes it with the lower mandible to the finest pulp, thus differing from other parrots in the mode of taking food. In the form of its tongue it differs also from other birds of the kind. A French naturalist read a memoir on this organ before the Academy of Sciences at Paris, in which he aptly compared it, in its uses, to the trunk of an elephant. In its manners it is gentle and familiar, and when approached raises a cry which may be compared to a hoarse croaking. In its gait it resembles the rook, and walks much better than most of the climbing family.

From the general conformation of the parrots, as well as the arrangement and strength of their toes, they climb very easily, assisting themselves greatly with their hooked bill, but walk rather awkwardly on the ground, from the shortness and wide separation of their legs. The bill of the parrot is moveable in both mandibles, the upper being joined to the skull by a membrane which acts like a hinge; while in other birds the upper beak forms part of the skull. By this curious contrivance they can open their bills widely, which the hooked form of the beak would not otherwise allow them to do. The structure of the wings varies greatly in the different species: in general they are short, and as their bodies are bulky, they cannot consequently rise to any great height without difficulty; but when once they gain a certain distance they fly easily, and some of them with rapidity. The number of feathers in the tail is always twelve, and these, both in length and form, are very varied in the different species, some being arrow or spear-shaped, others straight and square.

In eating, parrots make great use of the feet, which they employ like hands, holding the food firmly with the claws of one, while they support themselves on the other. From the hooked shape of their bills, they find it more convenient to turn their food in an outward direction, instead of, like monkeys and other animals, turning it towards their mouths.

The whole tribe are fond of water, washing and bathing themselves many times during the day in streams and marshy places; and having shaken the water from their plumage, seem greatly to enjoy spreading their beautiful wings to dry in the sun.

THE PARROT

A DOMESTIC ANECDOTEThe deep affections of the breast,That Heaven to living things imparts,Are not exclusively possess'dBy human hearts.A parrot, from the Spanish Main,Full young, and early-caged, came o'er,With bright wings, to the bleak domainOf Mulla's shore.To spicy groves, where he had wonHis plumage of resplendent hue—His native fruits, and skies, and sun—He bade adieu.For these he changed the smoke of turf,A heathery land and misty sky;And turn'd on rocks and raging surfHis golden eye.But, petted, in our climate cold,He lived and chatter'd many a day;Until, with age, from green and goldHis wings grew grey.At last, when blind and seeming dumb,He scolded, laugh'd, and spoke no more,A Spanish stranger chanced to comeTo Mulla's shore.He hail'd the bird in Spanish speech,The bird in Spanish speech replied:Flapt round his cage with joyous screech—Dropt down and died.CAMPBELL.THE STARLING

'Tis true, said I, correcting the proposition—the Bastile is not an evil to be despised; but strip it of its towers, fill the fosse, unbarricade the doors, call it simply a confinement, and suppose it is some tyrant of a distemper, and not a man which holds you in it, the evil vanishes, and you bear the other half without complaint. I was interrupted in the heyday of this soliloquy, with a voice which I took to be of a child, which complained "It could not get out." I looked up and down the passage, and seeing neither man, woman, or child, I went out without further attention. In my return back through the passage, I heard the same words repeated twice over; and looking up, I saw it was a starling, hung in a little cage; "I can't get out, I can't get out," said the starling. I stood looking at the bird; and to every person who came through the passage, it ran fluttering to the side towards which they approached it with the same lamentation of its captivity. "I can't get out," said the starling. "Then I will let you out," said I, "cost what it will;" so I turned about the cage to get at the door—it was twisted and double twisted so fast with wire there was no getting it open without pulling the cage to pieces; I took both hands to it. The bird flew to the place where I was attempting his deliverance, and thrusting his head through the trellis, pressed his breast against it, as if impatient. "I fear, poor creature," said I, "I cannot set thee at liberty." "No," said the starling; "I can't get out, I can't get out," said the starling.

I vow, I never had my affections more tenderly awakened; nor do I remember an incident in my life, where the dissipated spirits to which my reason had been a bubble were so suddenly called home. Mechanical as the notes were, yet so true in tune to nature were they chaunted, that in one moment they overthrew all my systematic reasonings upon the Bastile, and I heavily walked up-stairs unsaying every word I had said in going down them.

Sterne.THE CAR OF JUGGERNAUT

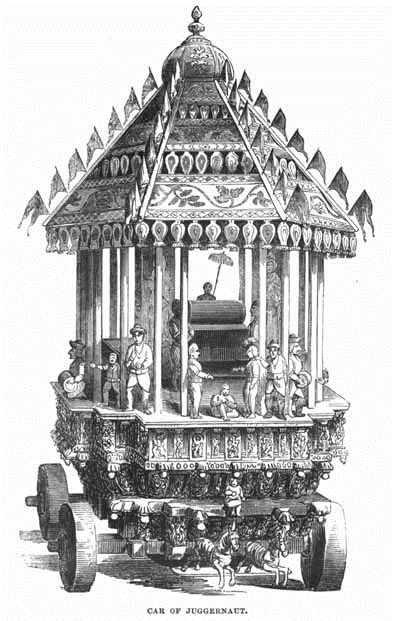

Juggernaut is the principal idol worshipped by the Hindoos, and to his temple, which is at Pooree, are attached no less than four thousand priests and servants; of these one set are called Pundahs. In the autumn of the year they start on a journey through India, preaching in every town and village the advantages of a pilgrimage to Juggernaut, after which they conduct to Pooree large bodies of pilgrims for the Rath Justra, or Car Festival, which takes place in May or June. This is the principal festival, and the number of devotees varies from about 80,000 to 150,000. No European, Mussulman, or low cast Hindoo is admitted into the temple; we can therefore only speak from report of what goes on inside. Mr. Acland, in his manners and customs of India, gives us the following amusing account of this celebrated idol:—

"Juggernaut represents the ninth incarnation of Vishnoo, a Hindoo deity, and consists of a mere block of sacred wood, in the centre of which is said to be concealed a fragment of the original idol, which was fashioned by Vishnoo himself. The features and all the external parts are formed of a mixture of mud and cow-dung, painted. Every morning the idol undergoes his ablutions; but, as the paint would not stand the washing, the priests adopt a very ingenious plan—they hold a mirror in front of the image and wash his reflection. Every evening he is put to bed; but, as the idol is very unwieldy, they place the bedstead in front of him, and on that they lay a small image. Offerings are made to him by pilgrims and others, of rice, money, jewels, elephants, &c., the Rajah of Knoudah and the priests being his joint treasurers. On the day of the festival, three cars, between fifty and sixty feet in height, are brought to the gate of the temple; the idols are then taken out by the priests, Juggernaut having golden arms and diamond eyes for that one day, and by means of pulleys are hauled up and placed in their respective carriages: to these enormous ropes are attached, and the assembled thousands with loud shouts proceed to drag the idols to Juggernaut's country-house, a small temple about a mile distant. This occupies several days, and the idols are then brought back to their regular stations. The Hindoos believe that every person who aids in dragging the cars receives pardon for all his past sins; but the fact that people throw themselves under the wheels of the cars, appears to have been an European conjecture, arising from the numerous deaths that occur from accidents at the time the immense cars are in progress."

These cars have an imposing air, from their great size and loftiness: the wheels are six feet in diameter; but every part of the ornament is of the meanest and most paltry description, save only the covering of striped and spangled broad-cloth, the splendid and gorgeous effect of which makes up in a great measure for other deficiencies.

During the period the pilgrims remain at Pooree they are not allowed to eat anything but what has been offered to the idol, and that they have to buy at a high price from the priests.

CYPRUS

Cyprus, an island in the Levant, is said to have taken its name from the number of shrubs of that name with which it once abounded. From this tall shrub, the cypress, its ancient inhabitants made an oil of a very delicious flavour, which was an article of great importance in their commerce, and is still in great repute among Eastern nations. It once, too, abounded with forests of olive trees; and immense cisterns are still to be seen, which have been erected for the purpose of preserving the oil which the olive yielded.

Near the centre of the island stands Nicotia, the capital, and the residence of the governor, who now occupies one of the palaces of its ancient sovereigns. The palaces are remarkable for the beauty of their architecture, but are abandoned by their Turkish masters to the destructive hand of time. The church of St. Sophia, in this place, is built in the Gothic style, and is said to have been erected by the Emperor Justinian. Here the Christian Kings of Cyprus were formerly crowned; but it is now converted into a mosque.

The island was formerly divided into nine kingdoms, and was famous for its superb edifices, its elegant temples, and its riches, but can now boast of nothing but its ruins, which will tell to distant times the greatness from which it has fallen.

The southern coast of this island is exposed to the hot winds from all directions. During a squall from the north-east, the temperature has been described as so scorching, that the skin instantly peeled from the lips, a tendency to sneeze was excited, accompanied with great pain in the eyes, and chapping of the hands and face. The heats are sometimes so excessive, that persons going out without an umbrella are liable to suffer from coup de soleil, or sun-stroke; and the inhabitants, especially of the lower class, in order to guard against it, wrap up their heads in a large turban, over which in their journeys they plait a thick shawl many times folded. They seldom, however, venture out of their houses during mid-day, and all journeys, even those of caravans, are performed in the night. Rains are also rare in the summer season, and long droughts banish vegetation, and attract numberless columns of locusts, which destroy the plants and fruits.

The soil, though very fertile, is rarely cultivated, the Greeks being so oppressed by their Turkish masters that they dare not cultivate the rich plains which surround them, as the produce would be taken from them; and their whole object is to collect together during the year as much grain as is barely sufficient to pay their tax to the Governor, the omission of which is often punished by torture or even by death.

The carob, or St. John's bread-tree, is plentiful; and the long thick pods which it produces are exported in considerable quantities to Syria and Egypt. The succulent pulp which the pod contains is sometimes employed in those countries instead of sugar and honey, and is often used in preserving other fruits. The vine grows here perhaps in greater perfection than in any other part of the world, and the wine of the island is celebrated all over the Levant.

THE RATTLESNAKE