полная версия

полная версияThe Illustrated London Reading Book

Burns, in his "Lament of Mary, Queen of Scots," touchingly expresses the weary feelings that must have existed in the breast of the Royal captive:—

"Oh, soon to me may summer sunsNae mair light up the morn!Nae mair to me the autumn windsWave o'er the yellow corn!And in the narrow house of death,Let winter round me rave;And the next flowers that deck the spring,Bloom on my peaceful grave."TUBULAR RAILWAY BRIDGES

In the year 1850, a vast line of railway was completed from Chester to Holyhead, for the conveyance of the Royal mails, of goods and passengers, and of her Majesty's troops and artillery, between London and Dublin—Holyhead being the most desirable point at which to effect this communication with Ireland. Upon this railway are two stupendous bridges, which are the most perfect examples of engineering skill ever executed in England, or in any other country.

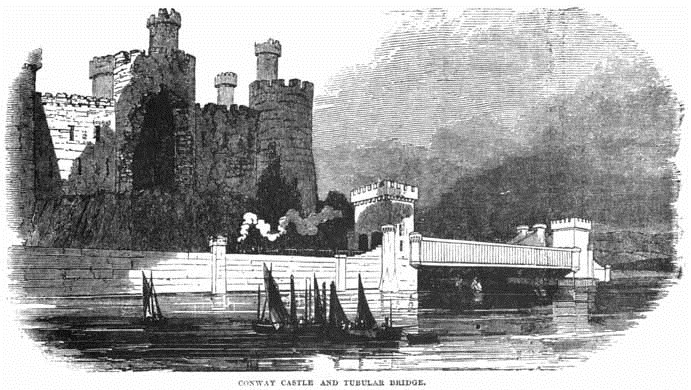

The first of these bridges carries the railway across the river Conway, close to the ancient castle built by Edward I. in order to bridle his new subjects, the Welsh.

The Conway bridge consists of a tube, or long, huge chest, the ends of which rest upon stone piers, built to correspond with the architecture of the old castle. The tube is made of wrought-iron plates, varying in thickness from a quarter of an inch to one inch, riveted together, and strengthened by irons in the form of the letter T; and, to give additional strength to the whole, a series of cells is formed at the bottom and top of the tube, between an inner ceiling and floor and the exterior plates; the iron plates which form the cells being riveted and held in their places by angle irons. The space between the sides of the tube is 14 feet; and the height of the whole, inclusive of the cells, is 22 feet 3-1/2 inches at the ends, and 25 feet 6 inches at the centre. The total length of the tube is 412 feet. One end of the tube is fixed to the masonry of the pier; but the other is so arranged as to allow for the expansion of the metal by changes of the temperature of the atmosphere, and it therefore, rests upon eleven rollers of iron, running upon a bed-plate; and, that the whole weight of the tube may not be carried by these rollers, six girders are carried over the tube, and riveted to the upper parts of its sides, which rest upon twelve balls of gun-metal running in grooves, which are fixed to iron beams let into the masonry.

The second of these vast railway bridges crosses the Menai Straits, which separate Caernarvon from the island of Anglesey. It is constructed a good hundred feet above high-water level, to enable large vessels to sail beneath it; and in building it, neither scaffolding nor centering was used.

The abutments on either side of the Straits are huge piles of masonry. That on the Anglesey side is 143 feet high, and 173 feet long. The wing walls of both terminate in splendid pedestals, and on each are two colossal lions, of Egyptian design; each being 25 feet long, 12 feet high though crouched, 9 feet abaft the body, and each paw 2 feet 1 inches. Each weighs 30 tons. The towers for supporting the tube are of a like magnitude with the entire work. The great Britannia Tower, in the centre of the Straits, is 62 feet by 52 feet at its base; its total height from the bottom, 230 feet; it contains 148,625 cubic feet of limestone, and 144,625 of sandstone; it weighs 20,000 tons; and there are 387 tons of cast iron built into it in the shape of beams and girders. It sustains the four ends of the four long iron tubes which span the Straits from shore to shore. The total quantity of stone contained in the bridge is 1,500,000 cubic feet. The side towers stand at a clear distance of 460 feet from the great central tower; and, again, the abutments stand at a distance from the side towers of 230 feet, giving the entire bridge a total length of 1849 feet, correspond ing with the date of the year of its construction. The side or land towers are each 62 feet by 52 feet at the base, and 190 feet high; they contain 210 tons of cast iron.

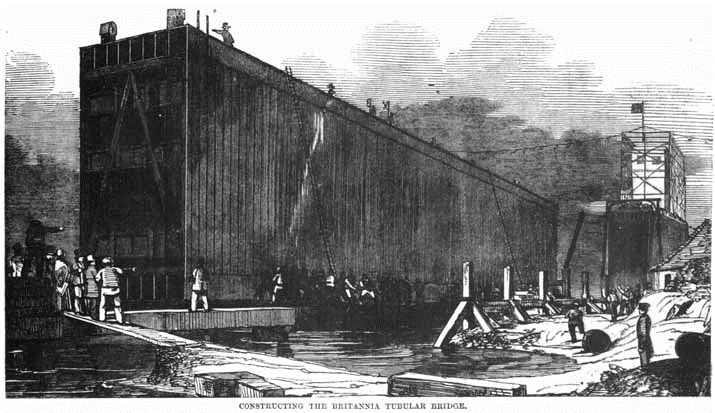

The length of the great tube is exactly 470 feet, being 12 feet longer than the clear space between the towers, and the greatest span ever yet attempted. The greatest height of the tube is in the centre—30 feet, and diminishing towards the end to 22 feet. Each tube consists of sides, top and bottom, all formed of long, narrow wrought-iron plates, varying in length from 12 feet downward. These plates are of the same manufacture as those for making boilers, varying in thickness from three-eighths to three-fourths of an inch. Some of them weigh nearly 7 cwt., and are amongst the largest it is possible to roll with any existing machinery. The connexion between top, bottom, and sides is made much more substantial by triangular pieces of thick plate, riveted in across the corners, to enable the tube to resist the cross or twisting strain to which it will be exposed from the heavy and long-continued gales of wind that, sweeping up the Channel, will assail it in its lofty and unprotected position. The rivets, of which there are 2,000,000—each tube containing 327,000—are more than an inch in diameter. They are placed in rows, and were put in the holes red hot, and beaten with heavy hammers. In cooling, they contracted strongly, and drew the plates together so powerfully that it required a force of from 1 to 6 tons to each rivet, to cause the plates to slide over each other. The weight of wrought iron in the great tube is 1600 tons.

Each of these vast bridge tubes was constructed on the shore, then floated to the base of the piers, or bridge towers, and raised to its proper elevation by hydraulic machinery, the largest in the world, and the most powerful ever constructed. For the Britannia Bridge, this consisted of two vast presses, one of which has power equal to that of 30,000 men, and it lifted the largest tube six feet in half an hour.

The Britannia tubes being in two lines, are passages for the up and down trains across the Straits. Each of the tubes has been compared to the Burlington Arcade, in Piccadilly; and the labour of placing this tube upon the piers has been assimilated to that of raising the Arcade upon the summit of the spire of St. James's Church, if surrounded with water.

Each line of tube is 1513 feet in length; far surpassing in size any piece of wrought-iron work ever before put together; and its weight is 5000 tons, being nearly equal to that of two 120-gun ships, having on board, ready for sea, guns, provisions, and crew. The plate-iron covering of the tubes is not thicker than the hide of an elephant, and scarcely thicker than the bark of an oak-tree; whilst one of the large tubes, if placed on its end in St. Paul's churchyard, would reach 107 feet higher than the cross of the cathedral.

THE MARINERS OF ENGLAND

Ye mariners of England!Who guard our native seas,Whose flag has braved a thousand yearsThe battle and the breeze,Your glorious standard launch again,To match another foe,And sweep through the deepWhile the stormy tempests blow;While the battle rages long and loud,And the stormy tempests blow.The spirits of your fathersShall start from every wave!For the deck it was their field of fame,And Ocean was their grave;Where Blake and mighty Nelson fell,Your manly hearts shall glow,As ye sweep through the deep,While the stormy tempests blow;While the battle rages long and loud,And the stormy tempests blow.Britannia needs no bulwarks,No towers along the steep;Her march is o'er the mountain waves,Her home is on the deep:With thunders from her native oak,She quells the floods below,As they roar on the shore,When the stormy tempests blow;When the battle rages long and loud,And the stormy tempests blow.The meteor-flag of EnglandShall yet terrific burn,Till danger's troubled night depart,And the star of peace return.Then, then, ye ocean-warriors!Our song and feast shall flowTo the fame of your name,When the storm has ceased to blow;When the fiery fight is heard no more,And the storm has ceased to blow.Campbell.KAFFIR LETTER-CARRIER

"I knew" (says the pleasing writer of "Letters from Sierra Leone") "that the long-looked-for vessel had at length furled her sails and dropped anchor in the bay. She was from England, and I waited, expecting every minute to feast my eyes upon at least one letter; but I remembered how unreasonable it was to suppose that any person would come up with letters to this lonely place at so late an hour, and that it behoved me to exercise the grace of patience until next day. However, between ten and eleven o'clock, a loud shouting and knocking aroused the household, and the door was opened to a trusty Kroo messenger, who, although one of a tribe who would visit any of its members in their own country with death, who could 'savey white man's book,' seemed to comprehend something of our feelings at receiving letters, as I overheard him exclaim, with evident glee, 'Ah! massa! here de right book come at last.' Every thing, whether a brown-paper parcel, a newspaper, an official despatch, a private letter or note is here denominated a 'book,' and this man understood well that newspapers are never received so gladly amongst 'books' from England as letters." The Kaffir, in the Engraving, was sketched from one employed to convey letters in the South African settlements; he carries his document in a split at the end of a cane.

It is a singular sight in India to see the catamarans which put off from some parts of the coast, as soon as ships come in sight, either to bear on board or to convey from thence letters or messages. These frail vessels are composed of thin cocoa-tree logs, lashed together, and big enough to carry one, or, at most, two persons. In one of these a small sail is fixed, and the navigator steers with a little paddle; the float itself is almost entirely sunk in the water, so that the effect is very singular—a sail sweeping along the surface with a man behind it, and apparently nothing to support them. Those which have no sails are consequently invisible and the men have the appearance of treading the water and performing evolutions with a racket. In very rough weather the men lash themselves to their little rafts but in ordinary seas they seem, though frequently washed off, to regard such accidents as mere trifles, being naked all but a wax cloth cap in which they keep any letters they may have to convey to ships in the roads, and swimming like fish. Their only danger is from sharks, which are said to abound. These cannot hurt them while on their floats; but woe be to them if they catch them while separated from that defence. Yet, even then, the case is not quite hopeless, since the shark can only attack them from below; and a rapid dive, if not in very deep water, will sometimes save them.

THE SEASONS

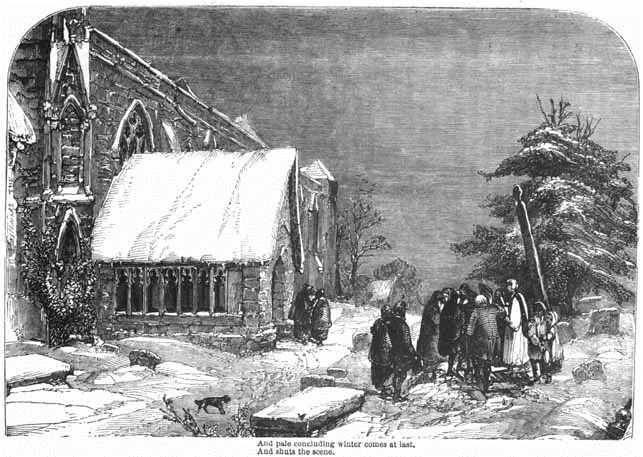

WINTERSee, Winter comes to rule the varied year,Sullen and sad, with all his rising train—Vapours, and clouds, and storms. Be these my theme,These—that exalt the soul to solemn thoughtAnd heavenly musing. Welcome, kindred glooms;Congenial horrors, hail: with frequent foot,Pleased have I, in my cheerful morn of life,When nursed by careless solitude I lived,And sung of nature with unceasing joy;Pleased have I wander'd through your rough domain,Trod the pure virgin snows, myself as pure;Heard the winds roar, and the big torrent burst,Or seen the deep-fermenting tempest brew'dIn the grim evening sky.Nature! great parent! whose unceasing handRolls round the seasons of the changeful year,How mighty, how majestic are thy works!With what a pleasing dread they swell the soul,That sees astonish'd, and astonish'd sings!Ye, too, ye winds! that now begin to blowWith boisterous sweep, I raise my voice to you.Where are your stores, ye powerful beings, say,Where your aerial magazines reservedTo swell the brooding terrors of the storm?In what far distant region of the sky,Hush'd in deep silence, sleep ye when 'tis calm?'Tis done; dread Winter spreads his latest glooms,And reigns tremendous o'er the conquer'd year.How dead the vegetable kingdom lies!How dumb the tuneful! Horror wide extendsHis desolate domain. Behold, fond man!See here thy pictured life! Pass some few yearsThy flowering spring, thy summer's ardent strength,And sober autumn fading into age,The pale concluding winter comes at lastThe shuts the scene. Ah! whither now are fledThose dreams of greatness? those unsolid hopesOf happiness? those longings after fame?Those restless cares? those busy bustling days?Those gay-spent festive nights? those veering thoughts,Lost between good and ill, that shared thy life?All now are vanish'd; virtue sole survives,Immortal, never-failing friend of man—His guide to happiness on high.Thomson.

ON MUSIC

There are few who have not felt the charms of music, and acknowledged its expressions to he intelligible to the heart. It is a language of delightful sensations, that is far more eloquent than words: it breathes to the ear the clearest intimations; but how it was learned, to what origin we owe it, or what is the meaning of some of its most affecting strains, we know not.

We feel plainly that music touches and gently agitates the agreeable and sublime passions; that it wraps us in melancholy, and elevates us to joy; that it dissolves and inflames; that it melts us into tenderness, and rouses into rage: but its strokes are so fine and delicate, that, like a tragedy, even the passions that are wounded please; its sorrows are charming, and its rage heroic and delightful. As people feel the particular passions with different degrees of force, their taste of harmony must proportionably vary. Music, then, is a language directed to the passions; but the rudest passions put on a new nature, and become pleasing in harmony: let me add, also, that it awakens some passions which we perceive not in ordinary life. Particularly the most elevated sensation of music arises from a confused perception of ideal or visionary beauty and rapture, which is sufficiently perceivable to fire the imagination, but not clear enough to become an object of knowledge. This shadowy beauty the mind attempts, with a languishing curiosity, to collect into a distinct object of view and comprehension; but it sinks and escapes, like the dissolving ideas of a delightful dream, that are neither within the reach of the memory, nor yet totally fled. The noblest charm of music, then, though real and affecting, seems too confused and fluid to be collected into a distinct idea.

Harmony is always understood by the crowd, and almost always mistaken by musicians. The present Italian taste for music is exactly correspondent to the taste for tragi-comedy, that about a century ago gained ground upon the stage. The musicians of the present day are charmed at the union they form between the grave and the fantastic, and at the surprising transitions they make between extremes, while every hearer who has the least remainder of the taste of nature left, is shocked at the strange jargon. If the same taste should prevail in painting, we must soon expect to see the woman's head, a horse's body, and a fish's tail, united by soft gradations, greatly admired at our public exhibitions. Musical gentlemen should take particular care to preserve in its full vigour and sensibility their original natural taste, which alone feels and discovers the true beauty of music.

If Milton, Shakspeare, or Dryden had been born with the same genius and inspiration for music as for poetry, and had passed through the practical part without corrupting the natural taste, or blending with it any prepossession in favour of sleights and dexterities of hand, then would their notes be tuned to passions and to sentiments as natural and expressive as the tones and modulations of the voice in discourse. The music and the thought would not make different expressions; the hearers would only think impetuously; and the effect of the music would be to give the ideas a tumultuous violence and divine impulse upon the mind. Any person conversant with the classic poets, sees instantly that the passionate power of music I speak of, was perfectly understood and practised by the ancients—that the Muses of the Greeks always sung, and their song was the echo of the subject, which swelled their poetry into enthusiasm and rapture. An inquiry into the nature and merits of the ancient music, and a comparison thereof with modern composition, by a person of poetic genius and an admirer of harmony, who is free from the shackles of practice, and the prejudices of the mode, aided by the countenance of a few men of rank, of elevated and true taste, would probably lay the present half-Gothic mode of music in ruins, like those towers of whose little laboured ornaments it is an exact picture, and restore the Grecian taste of passionate harmony once more to the delight and wonder of mankind. But as from the disposition of things, and the force of fashion, we cannot hope in our time to rescue the sacred lyre, and see it put into the hands of men of genius, I can only recall you to your own natural feeling of harmony and observe to you, that its emotions are not found in the laboured, fantastic, and surprising compositions that form the modern style of music: but you meet them in some few pieces that are the growth of wild unvitiated taste; you discover them in the swelling sounds that wrap us in imaginary grandeur; in those plaintive notes that make us in love with woe; in the tones that utter the lover's sighs, and fluctuate the breast with gentle pain; in the noble strokes that coil up the courage and fury of the soul, or that lull it in confused visions of joy; in short, in those affecting strains that find their way to the inmost recesses of the heart,

Untwisting all the chains that tieThe hidden soul of harmony.Milton.Usher.THE AFFLICTED POOR

Say ye—oppress'd by some fantastic woes,Some jarring nerve that baffles your repose,Who press the downy couch while slaves advanceWith timid eye to read the distant glance;Who with sad pray'rs the weary doctor tease,To name the nameless, ever new disease;Who with mock patience dire complaint endure,Which real pain, and that alone, can cure:How would ye bear in real pain to lie,Despised, neglected, left alone to die?How would ye bear to draw your latest breath,Where all that's wretched paves the way for death?Such is that room which one rude beam divides,And naked rafters form the sloping sides;Where the vile bands that bind the thatch are seen,And lath and mud are all that lie between,Save one dull pane that coarsely patch'd gives wayTo the rude tempest, yet excludes the day:There, on a matted flock with dust o'erspread,The drooping wretch reclines his languid head!For him no hand the cordial cup supplies,Nor wipes the tear which stagnates in his eyes;No friends, with soft discourse, his pangs beguile.Nor promise hope till sickness wears a smile.Crabbe.

MIDNIGHT THOUGHTS

Thou, who didst put to flightPrimeval silence, when the morning stars,Exulting, shouted o'er the rising ball:O Thou! whose word from solid darkness struckThat spark, the sun, strike wisdom from my soul;My soul which flies to thee, her trust her treasure,As misers to their gold, while others rest:Through this opaque of nature and of soul,This double night, transmit one pitying ray,To lighten and to cheer. Oh, lead my mind,(A mind that fain would wander from its woe,)Lead it through various scenes of life and death,And from each scene the noblest truths inspire.Nor less inspire my conduct, than my song;Teach my best reason, reason; my best willTeach rectitude; and fix my firm resolveWisdom to wed, and pay her long arrear;Nor let the phial of thy vengeance, pour'dOn this devoted head, be pour'd in vain.The bell strikes One. We take no note of timeBut from its loss; to give it then a tongueIs wise in man. As if an angel spoke,I feel the solemn sound. If heard aright,It is the knell of my departed hours.Where are they? with the years beyond the flood!It is the signal that demands dispatch:How much is to be done! My hopes and fearsStart up alarm'd, and o'er life's narrow vergeLook down—on what? A fathomless abyss!A dread eternity! How surely mine!And can eternity belong to me,Poor pensioner on the bounties of an hour?How poor, how rich, how abject, how august,How complicate, how wonderful is man!How passing wonder He who made him such!Who center'd in our make such strange extremes—From different natures, marvellously mix'd:Connexion exquisite! of distant worldsDistinguish'd link in being's endless chain!Midway from nothing to the Deity;A beam ethereal—sullied and absorpt!Though sullied and dishonour'd, still divine!Dim miniature of greatness absolute!An heir of glory! a frail child of dust!Helpless immortal! insect infinite!A worm! a god! I tremble at myself,And in myself am lost. At home a stranger.Thought wanders up and down, surprised, aghast,And wondering at her own. How reason reels!Oh, what a miracle to man is man!Triumphantly distress'd! what joy! what dreadAlternately transported and alarm'd!What can preserve my life, or what destroy?An angel's arm can't snatch me from the grave;Legions of angels can't confine me there.'Tis past conjecture; all things rise in proof.While o'er my limbs sleep's soft dominion spread,What though my soul fantastic measures trodO'er fairy fields, or mourn'd along the gloomOf pathless woods, or down the craggy steepHurl'd headlong, swam with pain the mantled pool,Or scaled the cliff, or danced on hollow windsWith antic shapes, wild natives of the brain!Her ceaseless flight, though devious, speaks her natureOf subtler essence than the trodden clod:Active, aerial, towering, unconfined,Unfetter'd with her gross companion's fall.Even silent night proclaims my soul immortal:Even silent night proclaims eternal day!For human weal Heaven husbands all events;Dull sleep instructs, nor sport vain dreams in vain.Young.