полная версия

полная версияThe Illustrated London Reading Book

THE ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH

Marvellous indeed have been the productions of modern scientific investigations, but none surpass the wonder-working Electro-magnetic Telegraphic Machine; and when Shakspeare, in the exercise of his unbounded imagination, made Puck, in obedience to Oberon's order to him—

"Be here againEre the leviathan can swim a league."reply—

"I'll put a girdle round the earthIn forty minutes"–how little did our immortal Bard think that this light fanciful offer of a "fairy" to "the King of the Fairies" would, in the nineteenth century, not only be substantially realised, but surpassed as follows:—

The electric telegraph would convey intelligence more than twenty-eight thousand times round the earth, while Puck, at his vaunted speed, was crawling round it only ONCE!

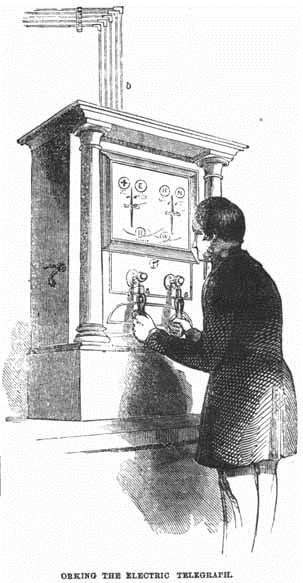

On every instrument there is a dial, on which are inscribed the names of the six or eight stations with which it usually communicates. When much business is to be transacted, a boy is necessary for each of these instruments; generally, however, one lad can, without practical difficulty, manage about three; but, as the whole of them are ready for work by night as well as by day, they are incessantly attended, in watches of eight hours each, by these satellite boys by day and by men at night.

As fast as the various messages for delivery, flying one after another from the ground-floor up the chimney, reach the level of the instruments, they are brought by the superintendent to the particular one by which they are to be communicated; and its boy, with the quickness characteristic of his age, then instantly sets to work.

His first process is by means of the electric current to sound a little bell, which simultaneously alarms all the stations on his line; and although the attention of the sentinel at each is thus attracted, yet it almost instantly evaporates from all excepting from that to the name of which he causes the electric needle to point, by which signal the clerk at that station instantly knows that the forthcoming question is addressed to him; and accordingly, by a corresponding signal, he announces to the London boy that he is ready to receive it. By means of a brass handle fixed to the dial, which the boy grasps in each hand, he now begins rapidly to spell off his information by certain twists of his wrists, each of which imparts to the needles on his dial, as well as to those on the dial of his distant correspondent, a convulsive movement designating the particular letter of the telegraphic alphabet required. By this arrangement he is enabled to transmit an ordinary-sized word in three seconds, or about twenty per minute. In the case of any accident to the wire of one of his needles, he can, by a different alphabet, transmit his message by a series of movements of the single needle, at the reduced rate of about eight or nine words per minute.

While a boy at one instrument is thus occupied in transmitting to—say Liverpool, a message, written by its London author in ink which is scarcely dry, another boy at the adjoining instrument is, by the reverse of the process, attentively reading the quivering movements of the needles of his dial, which, by a sort of St. Vitus's dance, are rapidly spelling to him a message, viâ the wires of the South Western Railway, say from Gosport, which word by word he repeats aloud to an assistant, who, seated by his side, writes it down (he receives it about as fast as his attendant can conveniently write it); on a sheet of; paper, which, as soon as the message is concluded, descends to the "booking-office." When inscribed in due form, it is without delay despatched to its destination, by messenger, cab, or express, according to order.

Sir F. B. Head.THE RAINBOW

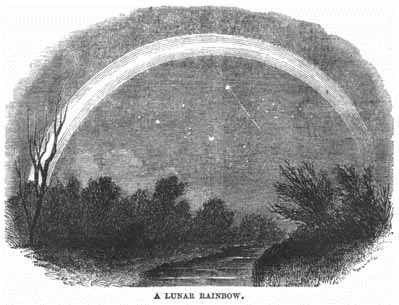

How glorious is thy girdle castO'er mountain, tower, and town,Or mirror'd in the ocean vast—A thousand fathoms down!As fresh in yon horizon dark,As young thy beauties seem,As when the eagle from the arkFirst sported in thy beam.For faithful to its sacred page,Heaven still rebuilds thy span,Nor let the type grow pale with age,That first spoke peace to man.Campbell.

The moon sometimes exhibits the extraordinary phenomenon of an iris or rainbow, by the refraction of her rays in drops of rain during the night-time. This appearance is said to occur only at the time of full moon, and to be indicative of stormy and rainy weather. One is described in the Philosophical Transactions as having been seen in 1810, during a thick rain; but, subsequent to that time, the same person gives an account of one which perhaps was the most extraordinary of which we have any record. It became visible about nine o'clock, and continued, though with very different degrees of brilliancy, until past two. At first, though a strongly marked bow, it was without colour, but afterwards became extremely vivid, the red, green, and purple being the most strongly marked. About twelve it was the most splendid in appearance. The wind was very high at the time, and a drizzling rain falling occasionally.

HOPE

LIGHTHOUSES

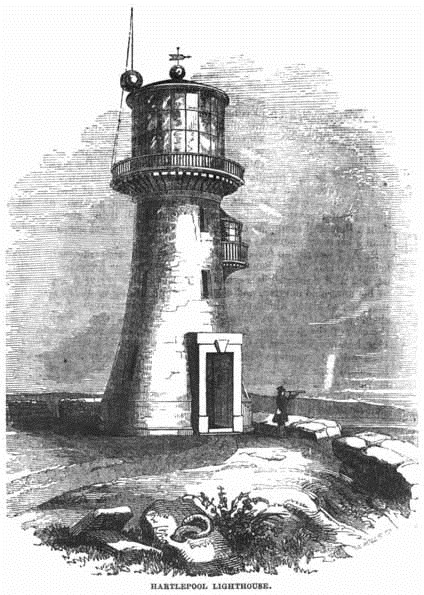

Hartlepool Lighthouse is a handsome structure of white freestone—the building itself being fifty feet in height; but, owing to the additional height of the cliff, the light is exhibited at an elevation of nearly eighty-five feet above high-water mark. On the eastern side of the building is placed a balcony, supporting a lantern, from which a small red light is exhibited, to indicate that state of the tide which will admit of the entrance of ships into the harbour; the corresponding signal in the daytime being a red ball hoisted to the top of the flag-staff. The lighthouse is furnished with an anemometer and tidal gauge; and its appointments are altogether of the most complete description. It is chiefly, however, with regard to the system adopted in the lighting arrangements that novelty presents itself.

The main object, in the instance of a light placed as a beacon to warn mariners of their proximity to a dangerous coast, is to obtain the greatest possible intensity and amount of penetrating power. A naked or simple light is therefore seldom, if ever employed; but whether it proceed from the combustion of oil or gas, it is equally necessary that it should be combined with some arrangement of optical apparatus, in order that the rays emitted may be collected, and projected in such a direction as to render them available to the object in view; and in all cases a highly-polished metal surface is employed as a reflector.

In the Hartlepool Lighthouse the illuminative medium is gas. The optical apparatus embraces three-fourths of the circumference of the circle which encloses the light, and the whole of the rays emanating from that part of the light opposed to the optical arrangement are reflected or refracted (as the case may be), so that they are projected from the lighthouse in such a direction as to be visible from the surface of the ocean.

INTEGRITY

Can anything (says Plato) be more delightful than the hearing or the speaking of truth? For this reason it is that there is no conversation so agreeable that of a man of integrity, who hears without any intention to betray, and speaks without any intention to deceive. As an advocate was pleading the cause of his client in Rome, before one of the praetors, he could only produce a single witness in a point where the law required the testimony of two persons; upon which the advocate insisted on the integrity of the person whom he had produced, but the praetor told him that where the law required two witnesses he would not accept of one, though it were Cato himself. Such a speech, from a person who sat at the head of a court of justice, while Cato was still living, shows us, more than a thousand examples, the high reputation this great man had gained among his contemporaries on account of his sincerity.

2. As I was sitting (says an ancient writer) with some senators of Bruges, before the gate of the Senate-House, a certain beggar presented himself to us, and with sighs and tears, and many lamentable gestures, expressed to us his miserable poverty, and asked our alms, telling us at the same time, that he had about him a private maim and a secret mischief, which very shame restrained him from discovering to the eyes of men. We all pitying the case of the poor man, gave him each of us something, and departed. One, however, amongst us took an opportunity to send his servant after him, with orders to inquire of him what that private infirmity might be which he found such cause to be ashamed of, and was so loth to discover. The servant overtook him, and delivered his commission: and after having diligently viewed his face, breast, arms, legs, and finding all his limbs in apparent soundness, "Why, friend," said he, "I see nothing whereof you have any such reason to complain." "Alas! sir," said the beggar, "the disease which afflicts me is far different from what you conceive, and is such as you cannot discern; yet it is an evil which hath crept over my whole body: it has passed through my very veins and marrow in such a manner that there is no member of my body that is able to work for my daily bread. This disease is by some called idleness, and by others sloth." The servant, hearing this singular apology, left him in great anger, and returned to his master with the above account; but before the company could send again to make further inquiry after him, the beggar had very prudently withdrawn himself.

3. Action, we are assured, keeps the soul in constant health; but idleness corrupts and rusts the mind; for a man of great abilities may by negligence and idleness become so mean and despicable as to be an incumbrance to society and a burthen to himself. When the Roman historians described an extraordinary man, it generally entered into his character, as an essential, that he was incredibili industriâ, diligentiâ singulari—of incredible industry, of singular diligence and application. And Cato, in Sallust, informs the Senate, that it was not so much the arms as the industry of their ancestors, which advanced the grandeur of Rome, and made her mistress of the world.

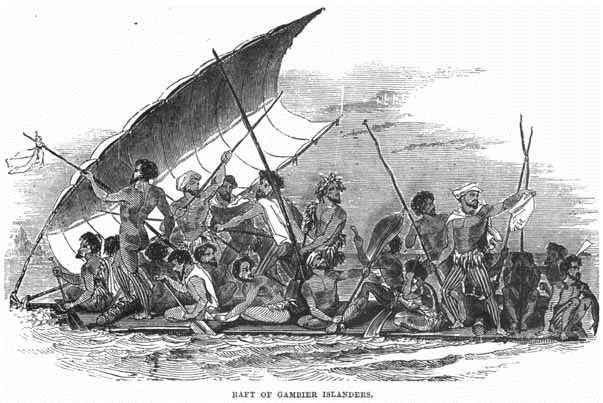

Dr. Dodd.RAFT OF GAMBIER ISLANDERS

The group in the Pacific Ocean called the Gambier Islands are but thinly inhabited, but possess a good harbour. Captain Beechey, in his "Narrative of a Voyage to the Pacific and Behring's Straits," tells us that several of the islands, especially the largest, have a fertile appearance. The Captain gives an interesting account of his interview with some of the natives, who approached the ship in rafts, carrying from sixteen to twenty men each, as represented in the Engraving.

"We were much pleased," says the Captain, "with the manner of lowering their matting sail, diverging on different courses, and working their paddles, in the use of which they had great power, and were well skilled, plying them together, or, to use a nautical phrase, 'keeping stroke.' They had no other weapons but long poles, and were quite naked, with the exception of a banana leaf cut into strips, and tied about their loins; and one or two persons wore white turbans." They timidly approached both the ship and the barge, but would upset any small boats within their reach; not, however, from any malicious intention, but from thoughtlessness and inquisitiveness. Captain Beechey approached them in the gig, and gave them several presents, for which they, in return, threw him some bundles of paste, tied up in large leaves, which was the common food of the natives. They tempted the Captain and his crew with cocoa-nuts and roots, and invited their approach by performing ludicrous dances; but, as soon as the visitors were within reach, all was confusion. A scuffle ensued, and on a gun being fired over their heads, all but four instantly plunged into the sea. The inhabitants of these islands are stated to be well-made, with upright and graceful figures. Tattooing seems to be very commonly practised, and some of the patterns are described as being very elegant.

CHRISTIAN FREEDOM

"He is the freeman whom the truth makes free,"Who first of all the bands of Satan breaks;Who breaks the bands of sin, and for his soul,In spite of fools, consulteth seriously;In spite of fashion, perseveres in good;In spite of wealth or poverty, upright;Who does as reason, not as fancy bids;Who hears Temptation sing, and yet turns notAside; sees Sin bedeck her flowery bed,And yet will not go up; feels at his heartThe sword unsheathed, yet will not sell the truth;Who, having power, has not the will to hurt;Who feels ashamed to be, or have a slave,Whom nought makes blush but sin, fears nought but God;Who, finally, in strong integrityOf soul, 'midst want, or riches, or disgraceUplifted, calmly sat, and heard the wavesOf stormy Folly breaking at his feet,Nor shrill with praise, nor hoarse with foal reproach,And both despised sincerely; seeking thisAlone, the approbation of his God,Which still with conscience witness'd to his peace.This, this is freedom, such as Angels use,And kindred to the liberty of God!Pollock.THE POLAR REGIONS

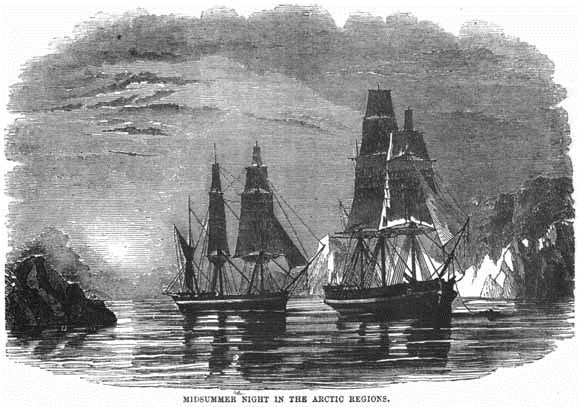

The adventurous spirit of Englishmen has caused them to fit out no less than sixty expeditions within the last three centuries and a half, with the sole object of discovering a north-west passage to India. Without attempting even to enumerate these baffled essays, we will at once carry our young readers to these dreary regions—dreary, merely because their capabilities are unsuited to the necessities which are obvious to all, yet performing their allotted office in the economy of the world, and manifesting the majesty and the glory of our great Creator.

Winter in the Arctic Circle is winter indeed: there is no sun to gladden with his beams the hearts of the voyagers; but all is wrapt in darkness, day and night, save when the moon chances to obtrude her faint rays, only to make visible the desolation of the scene. The approach of winter is strongly marked. Snow begins to fall in August, and the ground is covered to the depth of two or three feet before October. As the cold augments, the air bears its moisture in the form of a frozen fog, the icicles of which are so sharp as to be painful to the skin. The surface of the sea steams like a lime-kiln, caused by the water being still warmer than the superincumbent atmosphere. The mist at last clears, the water having become frozen, and darkness settles on the land. All is silence, broken only by the bark of the Arctic fox, or by the loud explosion of bursting rocks, as the frost penetrates their bosoms.

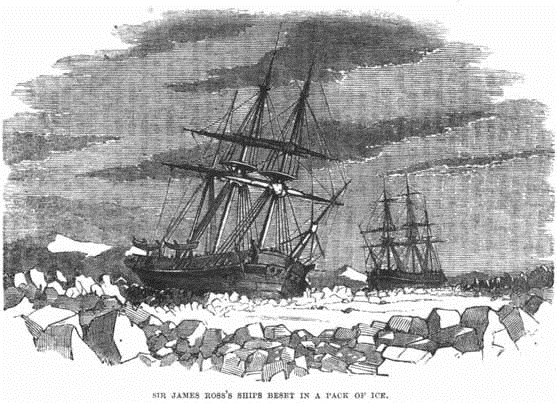

The crews of exploring vessels, which are frozen firmly in the ice in winter, spend almost the whole of their time in their ships, which in Sir James Ross's expedition (in 1848-49) were well warmed and ventilated. Where there has not been sufficient warmth, their provisions—even brandy—became so frozen as to require to be cut by a hatchet. The mercury in a barometer has frozen so that it might be beaten on an anvil.

As Sir James Ross went in search of Sir John Franklin, he adopted various methods of letting him know (if alive) of assistance being at hand. Provisions were deposited in several marked places; and on the excursions to make these deposits, they underwent terrible fatigue, as well as suffered severely from what is termed "snow blindness." But the greatest display of ingenuity was in capturing a number of white foxes, and fastening copper collars round their necks, on which was engraved a notice of the position of the ships and provisions. It was possible that these animals, which are known to travel very far in search of food, might be captured by the missing voyagers, who would thus be enabled to avail themselves of the assistance intended for them by their noble countrymen. The little foxes, in their desire to escape, sometimes tried to gnaw the bars of their traps; but the cold was so intense, that their tongues froze to the iron, and so their captors had to kill them, to release them from their misery, for they were never wantonly destroyed.

The great Painter of the Universe has not forgotten the embellishment of the Pole. One of the most beautiful phenomena in nature is the Aurora Borealis, or northern lights. It generally assumes the form of an arch, darting flashes of lilac, yellow, or white light towards the heights of heaven. Some travellers state that the aurora are accompanied by a crackling or hissing noise; but Captain Lyon, who listened for hours, says that this is not the case, and that it is merely that the imagination cannot picture these sudden bursts of light as unaccompanied by noise.

We will now bid farewell to winter, for with returning summer comes the open sea, and the vessels leave their wintry bed. This, however, is attended with much difficulty and danger. Canals have to be cut in the ice, through which to lead the ships to a less obstructed ocean; and, after this had been done in Sir James Ross's case, the ships were hemmed in by a pack of ice, fifty miles in circumference, and were carried along, utterly helpless, at the rate of eight or ten miles daily, for upwards of 250 miles—the navigators fearing the adverse winds might drive them on the rocky coast of Baffin's Bay. At length the wind changed, and carried them clear of ice and icebergs (detached masses of ice, sometimes several hundred feet in height) to the open sea, and back to their native land.

With all its dreariness, we owe much to the ice-bound Pole; to it we are indebted for the cooling breeze and the howling tempest—the beneficent tempest, in spite of all its desolation and woe. Evil and good in nature are comparative: the same thing does what is called harm in one sense, but incalculable good in another. So the tempest, that causes the wreck, and makes widows of happy wives and orphans of joyous children, sets in motion air that would else be stagnant, and become the breath of pestilence and the grave.

THE CROWN JEWELS

All the Crown Jewels, or Regalia, used by the Sovereign on great state occasions, are kept in the Tower of London, where they have been for nearly two centuries. The first express mention made of the Regalia being kept in this palatial fortress, occurs in the reign of Henry III., previously to which they were deposited either in the Treasury of the Temple, or in some religious house dependent upon the Crown. Seldom, however, did the jewels remain in the Tower for any length of time, for they were repeatedly pledged to meet the exigences of the Sovereign. An inventory of the jewels in the Tower, made by order of James I., is of great length; although Henry III., during the Lincolnshire rebellion, in 1536, greatly reduced the value and number of the Royal store. In the reign of Charles II., a desperate attempt was made by Colonel Blood and his accomplices to possess themselves of the Royal Jewels.

The Regalia were originally kept in a small building on the south side of the White Tower; but, in the reign of Charles I., they were transferred to a strong chamber in the Martin Tower, afterwards called the Jewel Tower. Here they remained until the fire in 1840; when being threatened with destruction from the flames which were raging near them, they were carried away by the warders, and placed for safety in the house of the Governor. In 1841 they were removed to the new Jewel-House, which is much more commodious than the old vaulted chamber in which they were previously shown.

The QUEEN'S, or IMPERIAL CROWN was made for the coronation of her present Majesty. It is composed of a cap of purple velvet, enclosed by hoops of silver, richly dight with gems, in the form shown in our Illustration. The arches rise almost to a point instead of being depressed, are covered with pearls, and are surmounted by an orb of brilliants. Upon this is placed a Maltese or cross pattee of brilliants. Four crosses and four fleurs-de-lis surmount the circlet, all composed of diamonds, the front cross containing the "inestimable sapphire," of the purest and deepest azure, more than two inches long, and an inch broad; and, in the circlet beneath it, is a rock ruby, of enormous size and exquisite colour, said to have been worn by the Black Prince at the battle of Cressy, and by Henry V. at the battle of Agincourt. The circlet is enriched with diamonds, emeralds, sapphires, and rubies. This crown was altered from the one constructed expressly for the coronation of King George IV.: the superb diadem then weighed 5-1/2 lb., and was worn by the King on his return in procession from the Abbey to the Hall at Westminster.

The OLD IMPERIAL CROWN (St. Edward's) is the one whose form is so familiar to us from its frequent representation on the coin of the realm, the Royal arms, &c. It was made for the coronation of Charles II., to replace the one broken up and sold during the Civil Wars, which was said to have been worn by Edward the Confessor. It is of gold, and consists of two arches crossing at the top, and rising from a rim or circlet of gold, over a cap of crimson velvet, lined with white taffeta, and turned up with ermine. The base of the arches on each side is covered by a cross pattee; between the crosses are four fleurs-de-lis of gold, which rise out of the circle: the whole of these are splendidly enriched with pearls and precious stones. On the top, at the intersection of the arches, which are somewhat depressed, are a mound and cross of gold the latter richly jewelled, and adorned with three pearls, one on the top, and one pendent at each limb.

The PRINCE OF WALES'S CROWN is of pure gold, unadorned with jewels. On occasions of state, it is placed before the seat occupied by the Heir-Apparent to the throne in the House of Lords.