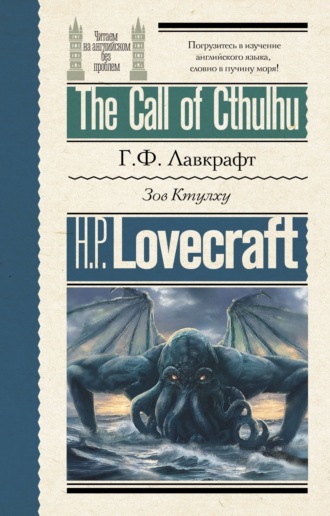

The Call of Cthulhu / Зов Ктулху

Полная версия

The Call of Cthulhu / Зов Ктулху

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 1926

Добавлена:

Серия «Читаем на английском без проблем»

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу