полная версия

полная версияTales of Old Japan

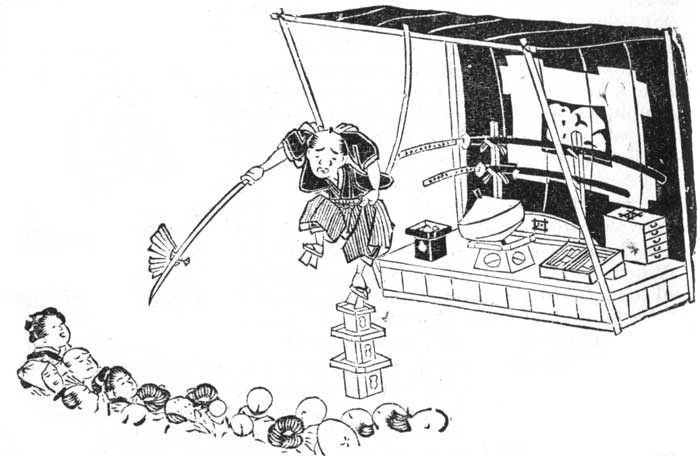

TRICKS OF SWORDSMANSHIP AT ASAKUSA.

Now Banzayémon, after he had killed Sanza on the Mound of the Yoshiwara, did not dare to show his face again in the house of Chôbei, the Father of the Otokodaté; for he knew that the two men, Tôken Gombei and Shirobei "the loose Colt," would not only bear an evil report of him, but would even kill him if he fell into their hands, so great had been their indignation at his cowardly Conduct; so he entered a company of mountebanks, and earned his living by showing tricks of swordsmanship, and selling tooth-powder at the Okuyama, at Asakusa.29 One day, as he was going towards Asakusa to ply his trade, he caught sight of a blind beggar, in whom, in spite of his poverty-stricken and altered appearance, he recognized the son of his enemy. Rightly he judged that, in spite of the boy's apparently helpless condition, the discovery boded no weal for him; so mounting to the upper storey of a tea-house hard by, he watched to see who should come to Kosanza's assistance. Nor had he to wait long, for presently he saw a second beggar come up and speak words of encouragement and kindness to the blind youth; and looking attentively, he saw that the new-comer was Umanosuké. Having thus discovered who was on his track, he went home and sought means of killing the two beggars; so he lay in wait and traced them to the poor hut where they dwelt, and one night, when he knew Umanosuké to be absent, he crept in. Kosanza, being blind, thought that the footsteps were those of Umanosuké, and jumped up to welcome him; but he, in his heartless cruelty, which not even the boy's piteous state could move, slew Kosanza as he helplessly stretched out his hands to feel for his friend. The deed was yet unfinished when Umanosuké returned, and, hearing a scuffle inside the hut, drew the sword which was hidden in his staff and rushed in; but Banzayémon, profiting by the darkness, eluded him and fled from the hut. Umanosuké followed swiftly after him; but just as he was on the point of catching him, Banzayémon, making a sweep backwards with his drawn sword, wounded Umanosuké in the thigh, so that he stumbled and fell, and the murderer, swift of foot, made good his escape. The wounded youth tried to pursue him again, but being compelled by the pain of his wound to desist, returned home and found his blind companion lying dead, weltering in his own blood. Cursing his unhappy fate, he called in the beggars of the fraternity to which he belonged, and between them they buried Kosanza, and he himself being too poor to procure a surgeon's aid, or to buy healing medicaments for his wound, became a cripple.

It was at this time that Shirai Gompachi, who was living under the protection of Chôbei, the Father of the Otokodaté, was in love with Komurasaki, the beautiful courtesan who lived at the sign of the Three Sea-shores, in the Yoshiwara. He had long exhausted the scanty supplies which he possessed, and was now in the habit of feeding his purse by murder and robbery, that he might have means to pursue his wild and extravagant life. One night, when he was out on his cutthroat business, his fellows, who had long suspected that he was after no good, sent one of their number, named Seibei, to watch him. Gompachi, little dreaming that any one was following him, swaggered along the street until he fell in with a wardsman, whom he cut down and robbed; but the booty proving small, he waited for a second chance, and, seeing a light moving in the distance, hid himself in the shadow of a large tub for catching rain-water till the bearer of the lantern should come up. When the man drew near, Gompachi saw that he was dressed as a traveller, and wore a long dirk; so he sprung out from his lurking-place and made to kill him; but the traveller nimbly jumped on one side, and proved no mean adversary, for he drew his dirk and fought stoutly for his life. However, he was no match for so skilful a swordsman as Gompachi, who, after a sharp struggle, dispatched him, and carried off his purse, which contained two hundred riyos. Overjoyed at having found so rich a prize, Gompachi was making off for the Yoshiwara, when Seibei, who, horror-stricken, had seen both murders, came up and began to upbraid him for his wickedness. But Gompachi was so smooth-spoken and so well liked by his comrades, that he easily persuaded Seibei to hush the matter up, and accompany him to the Yoshiwara for a little diversion. As they were talking by the way, Seibei said to Gompachi—

"I bought a new dirk the other day, but I have not had an opportunity to try it yet. You have had so much experience in swords that you ought to be a good judge. Pray look at this dirk, and tell me whether you think it good for anything."

"We'll soon see what sort of metal it is made of," answered Gompachi. "We'll just try it on the first beggar we come across."

At first Seibei was horrified by this cruel proposal, but by degrees he yielded to his companion's persuasions; and so they went on their way until Seibei spied out a crippled beggar lying asleep on the bank outside the Yoshiwara. The sound of their footsteps aroused the beggar, who seeing a Samurai and a wardsman pointing at him, and evidently speaking about him, thought that their consultation could bode him no good. So he pretended to be still asleep, watching them carefully all the while; and when Seibei went up to him, brandishing his dirk, the beggar, avoiding the blow, seized Seibei's arm, and twisting it round, flung him into the ditch below. Gompachi, seeing his companion's discomfiture, attacked the beggar, who, drawing a sword from his staff, made such lightning-swift passes that, crippled though he was, and unable to move his legs freely, Gompachi could not overpower him; and although Seibei crawled out of the ditch and came to his assistance, the beggar, nothing daunted, dealt his blows about him to such good purpose that he wounded Seibei in the temple and arm. Then Gompachi, reflecting that after all he had no quarrel with the beggar, and that he had better attend to Seibei's wounds than go on fighting to no purpose, drew Seibei away, leaving the beggar, who was too lame to follow them, in peace. When he examined Seibei's wounds, he found that they were so severe that they must give up their night's frolic and go home. So they went back to the house of Chôbei, the Father of the Otokodaté, and Seibei, afraid to show himself with his sword-cuts, feigned sickness, and went to bed. On the following morning Chôbei, happening to need his apprentice Seibei's services, sent for him, and was told that he was sick; so he went to the room, where he lay abed, and, to his astonishment, saw the cut upon his temple. At first the wounded man refused to answer any questions as to how he had been hurt; but at last, on being pressed by Chôbei, he told the whole story of what had taken place the night before. When Chôbei heard the tale, be guessed that the valiant beggar must be some noble Samurai in disguise, who, having a wrong to avenge, was biding his time to meet with his enemy; and wishing to help so brave a man, he went in the evening, with his two faithful apprentices, Tôken Gombei and Shirobei "the loose Colt," to the bank outside the Yoshiwara to seek out the beggar. The latter, not one whit frightened by the adventure of the previous night, had taken his place as usual, and was lying on the bank, when Chôbei came up to him, and said—

"Sir, I am Chôbei, the chief of the Otokodaté, at your service. I have learnt with deep regret that two of my men insulted and attacked you last night. However, happily, even Gompachi, famous swordsman though he be, was no match for you, and had to beat a retreat before you. I know, therefore, that you must be a noble Samurai, who by some ill chance have become a cripple and a beggar. Now, therefore, I pray you tell me all your story; for, humble wardsman as I am, I may be able to assist you, if you will condescend to allow me."

The cripple at first tried to shun Chôbei's questions; but at last, touched by the honesty and kindness of his speech, he replied—

"Sir, my name is Takagi Umanosuké, and I am a native of Yamato;" and then he went on to narrate all the misfortunes which the wickedness of Banzayémon had brought about.

"This is indeed a strange story," said Chôbei who had listened with indignation. "This Banzayémon, before I knew the blackness of his heart, was once under my protection. But after he murdered Sanza, hard by here, he was pursued by these two apprentices of mine, and since that day he has been no more to my house."

When he had introduced the two apprentices to Umanosuké, Chôbei pulled forth a suit of silk clothes befitting a gentleman, and having made the crippled youth lay aside his beggar's raiment, led him to a bath, and had his hair dressed. Then he bade Tôken Gombei lodge him and take charge of him, and, having sent for a famous physician, caused Umanosuké to undergo careful treatment for the wound in his thigh. In the course of two months the pain had almost disappeared, so that he could stand easily; and when, after another month, he could walk about a little, Chôbei removed him to his own house, pretending to his wife and apprentices that he was one of his own relations who had come on a visit to him.

After a while, when Umanosuké had become quite cured, he went one day to worship at a famous temple, and on his way home after dark he was overtaken by a shower of rain, and took shelter under the eaves of a house, in a part of the city called Yanagiwara, waiting for the sky to clear. Now it happened that this same night Gompachi had gone out on one of his bloody expeditions, to which his poverty and his love for Komurasaki drove him in spite of himself, and, seeing a Samurai standing in the gloom, he sprang upon him before he had recognized Umanosuké, whom he knew as a friend of his patron Chôbei. Umanosuké drew and defended himself, and soon contrived to slash Gompachi on the forehead; so that the latter, seeing himself overmatched, fled under the cover of the night. Umanosuké, fearing to hurt his recently healed wound, did not give chase, and went quietly back to Chôbei's house. When Gompachi returned home, he hatched a story to deceive Chôbei as to the cause of the wound on his forehead. Chôbei, however, having overheard Umanosuké reproving Gompachi for his wickedness, soon became aware of the truth; and not caring to keep a robber and murderer near him, gave Gompachi a present of money, and bade him return to his house no more.

And now Chôbei, seeing that Umanosuké had recovered his strength, divided his apprentices into bands, to hunt out Banzayémon, in order that the vendetta might be accomplished. It soon was reported to him that Banzayémon was earning his living among the mountebanks of Asakusa; so Chôbei communicated this intelligence to Umanosuké, who made his preparations accordingly; and on the following morning the two went to Asakusa, where Banzayémon was astonishing a crowd of country boors by exhibiting tricks with his sword.

Then Umanosuké, striding through the gaping rabble, shouted out—

"False, murderous coward, your day has come! I, Umanosuké, the son of Umanojô, have come to demand vengeance for the death of three innocent men who have perished by your treachery. If you are a man, defend yourself. This day shall your soul see hell!"

With these words he rushed furiously upon Banzayémon, who, seeing escape to be impossible, stood upon his guard. But his coward's heart quailed before the avenger, and he soon lay bleeding at his enemy's feet.

But who shall say how Umanosuké thanked Chôbei for his assistance; or how, when he had returned to his own country, he treasured up his gratitude in his heart, looking upon Chôbei as more than a second father?

Thus did Chôbei use his power to punish the wicked, and to reward the good—giving of his abundance to the poor, and succouring the unfortunate, so that his name was honoured far and near. It remains only to record the tragical manner of his death.

We have already told how my lord Midzuno Jiurozayémon, the chief of the associated nobles, had been foiled in his attempts to bring shame upon Chôbei, the Father of the Otokodaté; and how, on the contrary, the latter, by his ready wit, never failed to make the proud noble's weapons recoil upon him. The failure of these attempts rankled in the breast of Jiurozayémon, who hated Chôbei with an intense hatred, and sought to be revenged upon him. One day he sent a retainer to Chôbei's house with a message to the effect that on the following day my lord Jiurozayémon would be glad to see Chôbei at his house, and to offer him a cup of wine, in return for the cold macaroni with which his lordship had been feasted some time since. Chôbei immediately suspected that in sending this friendly summons the cunning noble was hiding a dagger in a smile; however, he knew that if he stayed away out of fear he would be branded as a coward, and made a laughing-stock for fools to jeer at. Not caring that Jiurozayémon should succeed in his desire to put him to shame, he sent for his favourite apprentice, Tôken Gombei, and said to him—

"I have been invited to a drinking-bout by Midzuno Jiurozayémon. I know full well that this is but a stratagem to requite me for having fooled him, and maybe his hatred will go the length of killing me. However, I shall go and take my chance; and if I detect any sign of foul play, I'll try to serve the world by ridding it of a tyrant, who passes his life in oppressing the helpless farmers and wardsmen. Now as, even if I succeed in killing him in his own house, my life must pay forfeit for the deed, do you come to-morrow night with a burying-tub,30 and fetch my corpse from this Jiurozayémon's house."

Tôken Gombei, when he heard the "Father" speak thus, was horrified, and tried to dissuade him from obeying the invitation. But Chôbei's mind was fixed, and, without heeding Gombei's remonstrances, he proceeded to give instructions as to the disposal of his property after his death, and to settle all his earthly affairs.

On the following day, towards noon, he made ready to go to Jiurozayémon's house, bidding one of his apprentices precede him with a complimentary present.31 Jiurozayémon, who was waiting with impatience for Chôbei to come, so soon as he heard of his arrival ordered his retainers to usher him into his presence; and Chôbei, having bade his apprentices without fail to come and fetch him that night, went into the house.

No sooner had he reached the room next to that in which Jiurozayémon was sitting than he saw that his suspicions of treachery were well founded; for two men with drawn swords rushed upon him, and tried to cut him down. Deftly avoiding their blows, however, he tripped up the one, and kicking the other in the ribs, sent him reeling and breathless against the wall; then, as calmly as if nothing had happened he presented himself before Jiurozayémon, who, peeping through a chink in the sliding-doors, had watched his retainers' failure.

"Welcome, welcome, Master Chôbei," said he. "I always had heard that you were a man of mettle, and I wanted to see what stuff you were made of; so I bade my retainers put your courage to the test. That was a masterly throw of yours. Well, you must excuse this churlish reception: come and sit down by me."

"Pray do not mention it, my lord," said Chôbei, smiling rather scornfully. "I know that my poor skill is not to be measured with that of a noble Samurai; and if these two good gentlemen had the worst of it just now, it was mere luck—that's all."

So, after the usual compliments had been exchanged, Chôbei sat down by Jiurozayémon, and the attendants brought in wine and condiments. Before they began to drink, however, Jiurozayémon said—

"You must be tired and exhausted with your walk this hot day, Master Chôbei. I thought that perhaps a bath might refresh you, so I ordered my men to get it ready for you. Would you not like to bathe and make yourself comfortable?"

Chôbei suspected that this was a trick to strip him, and take him unawares when he should have laid aside his dirk. However, he answered cheerfully—

"Your lordship is very good. I shall be glad to avail myself of your kind offer. Pray excuse me for a few moments."

So he went to the bath-room, and, leaving his clothes outside, he got into the bath, with the full conviction that it would be the place of his death. Yet he never trembled nor quailed, determined that, if he needs must die, no man should say he had been a coward. Then Jiurozayémon, calling to his attendants, said—

"Quick! lock the door of the bath-room! We hold him fast now. If he gets out, more than one life will pay the price of his. He's a match for any six of you in fair fight. Lock the door, I say, and light up the fire under the bath;32 and we'll boil him to death, and be rid of him. Quick, men, quick!"

So they locked the door, and fed the fire until the water hissed and bubbled within; and Chôbei, in his agony, tried to burst open the door, but Jiurozayémon ordered his men to thrust their spears through the partition wall and dispatch him. Two of the spears Chôbei clutched and broke short off; but at last he was struck by a mortal blow under the ribs, and died a brave man by the hands of cowards.

THE DEATH OF CHÔBEI OF BANDZUIN.

That evening Tôken Gombei, who, to the astonishment of Chôbei's wife, had bought a burying-tub, came, with seven other apprentices, to fetch the Father of the Otokodaté from Jiurozayémon's house; and when the retainers saw them, they mocked at them, and said—

"What, have you come to fetch your drunken master home in a litter?"

"Nay," answered Gombei, "but we have brought a coffin for his dead body, as he bade us."

When the retainers heard this, they marvelled at the courage of Chôbei, who had thus wittingly come to meet his fate. So Chôbei's corpse was placed in the burying-tub, and handed over to his apprentices, who swore to avenge his death. Far and wide, the poor and friendless mourned for this good man. His son Chômatsu inherited his property; and his wife remained a faithful widow until her dying day, praying that she might sit with him in paradise upon the cup of the same lotus-flower.

Many a time did the apprentices of Chôbei meet together to avenge him; but Jiurozayémon eluded all their efforts, until, having been imprisoned by the Government in the temple called Kanyeiji, at Uyéno, as is related in the story of "Kazuma's Revenge," he was placed beyond the reach of their hatred.

So lived and so died Chôbei of Bandzuin, the Father of the Otokodaté of Yedo.

NOTE ON ASAKUSA

Translated from a native book called the "Yedo Hanjôki," or Guide to the prosperous City of Yedo, and other sources.

Asakusa is the most bustling place in all Yedo. It is famous for the Temple Sensôji, on the hill of Kinriu, or the Golden Dragon, which from morning till night is thronged with visitors, rich and poor, old and young, flocking in sleeve to sleeve. The origin of the temple was as follows:—In the days of the Emperor Suiko, who reigned in the thirteenth century A.D., a certain noble, named Hashi no Nakatomo, fell into disgrace and left the Court; and having become a Rônin, or masterless man, he took up his abode on the Golden Dragon Hill, with two retainers, being brothers, named Hinokuma Hamanari and Hinokuma Takénari. These three men being reduced to great straits, and without means of earning their living, became fishermen. Now it happened that on the 6th day of the 3rd month of the 36th year of the reign of the Emperor Suiko (A.D. 1241), they went down in the morning to the Asakusa River to ply their trade; and having cast their nets took no fish, but at every throw they pulled up a figure of the Buddhist god Kwannon, which they threw into the river again. They sculled their boat away to another spot, but the same luck followed them, and nothing came to their nets save the figure of Kwannon. Struck by the miracle, they carried home the image, and, after fervent prayer, built a temple on the Golden Dragon Hill, in which they enshrined it. The temple thus founded was enriched by the benefactions of wealthy and pious persons, whose care raised its buildings to the dignity of the first temple in Yedo. Tradition says that the figure of Kwannon which was fished up in the net was one inch and eight-tenths in height.

The main hall of the temple is sixty feet square, and is adorned with much curious workmanship of gilding and of silvering, so that no place can be more excellently beautiful. There are two gates in front of it. The first is called the Gate of the Spirits of the Wind and of the Thunder, and is adorned with figures of those two gods. The Wind-god, whose likeness is that of a devil, carries the wind-bag; and the Thunder-god, who is also shaped like a devil, carries a drum and a drumstick.33 The second gate is called the Gate of the gods Niô, or the Two Princes, whose colossal statues, painted red, and hideous to look upon, stand on either side of it. Between the gates is an approach four hundred yards in length, which is occupied by the stalls of hucksters, who sell toys and trifles for women and children, and by foul and loathsome beggars. Passing through the gate of the gods Niô, the main hall of the temple strikes the eye. Countless niches and shrines of the gods stand outside it, and an old woman earns her livelihood at a tank filled with water, to which the votaries of the gods come and wash themselves that they may pray with clean hands. Inside are the images of the gods, lanterns, incense-burners, candlesticks, a huge moneybox, into which the offerings of the pious are thrown, and votive tablets34 representing the famous gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines, of old. Behind the chief building is a broad space called the okuyama, where young and pretty waitresses, well dressed and painted, invite the weary pilgrims and holiday-makers to refresh themselves with tea and sweetmeats. Here, too, are all sorts of sights to be seen, such as wild beasts, performing monkeys, automata, conjurers, wooden and paper figures, which take the place of the waxworks of the West, acrobats, and jesters for the amusement of women and children. Altogether it is a lively and a joyous scene; there is not its equal in the city.

At Asakusa, as indeed all over Yedo, are to be found fortunetellers, who prey upon the folly of the superstitious. With a treatise on physiognomy laid on a desk before them, they call out to this man that he has an ill-omened forehead, and to that man that the space between his nose and his lips is unlucky. Their tongues wag like flowing water until the passers-by are attracted to their stalls. If the seer finds a customer, he closes his eyes, and, lifting the divining-sticks reverently to his forehead, mutters incantations between his teeth. Then, suddenly parting the sticks in two bundles, he prophesies good or evil, according to the number in each. With a magnifying-glass he examines his dupe's face and the palms of his hands. By the fashion of his clothes and his general manner the prophet sees whether he is a countryman or from the city. "I am afraid, sir," says he, "you have not been altogether fortunate in life, but I foresee that great luck awaits you in two or three months;" or, like a clumsy doctor who makes his diagnosis according to his patient's fancies, if he sees his customer frowning and anxious, he adds, "Alas! in seven or eight months you must beware of great misfortune. But I cannot tell you all about it for a slight fee:" with a long sigh he lays down the divining-sticks on the desk, and the frightened boor pays a further fee to hear the sum of the misfortune which threatens him, until, with three feet of bamboo slips and three inches of tongue, the clever rascal has made the poor fool turn his purse inside out.

The class of diviners called Ichiko profess to give tidings of the dead, or of those who have gone to distant countries. The Ichiko exactly corresponds to the spirit medium of the West. The trade is followed by women, of from fifteen or sixteen to some fifty years of age, who walk about the streets, carrying on their backs a divining-box about a foot square; they have no shop or stall, but wander about, and are invited into their customers' houses. The ceremony of divination is very simple. A porcelain bowl filled with water is placed upon a tray, and the customer, having written the name of the person with whom he wishes to hold communion on a long slip of paper, rolls it into a spill, which he dips into the water, and thrice sprinkles the Ichiko, or medium. She, resting her elbow upon her divining-box, and leaning her head upon her hand, mutters prayers and incantations until she has summoned the soul of the dead or absent person, which takes possession of her, and answers questions through her mouth. The prophecies which the Ichiko utters during her trance are held in high esteem by the superstitious and vulgar.