полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

Dr. Coues found this species a very common winter resident in Arizona, arriving at Fort Whipple about October 10, soon becoming very abundant, and continuing so until the second week in April. Stragglers were seen until May 10.

Dr. Woodhouse also observed numbers of the western Snowbird on the San Francisco Mountains, in the month of October, where they were very abundant. Many specimens were obtained in Sitka by Mr. Bischoff. None have so far been recorded from the Aleutian Islands.

Dr. Kennerly frequently saw these birds near the Pueblo of Zuñi in New Mexico; in the months of October and November they were very abundant among the cedars to the westward of that settlement as far as the Little Colorado. Dr. Heermann also met with them near Fort Yuma in December, having previously noticed them during the fall, migrating in large flocks.

Mr. Aiken frequently found this species throughout the winter in Colorado. It was very common during March and the first of April. By May only a few straggling females were seen, and then they all disappeared.

The nests of this species have a general resemblance in structure to those of the common hyemalis. They are well constructed and remarkably symmetrical, made externally of mosses and other coarse materials, within which is very nicely woven an inner nest of fine, bent stems of grasses, lined with hair. The eggs, four or five in number, resemble those of the hyemalis, but are lighter. They have a ground-color of greenish-white, marked about the larger end with fine dots of reddish-brown. Their measurement is .75 by .60 of an inch.

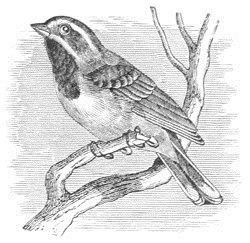

Junco caniceps, BairdRED-BACKED SNOWBIRDStruthus caniceps, Woodhouse, Pr. A. N. Sc. Phila. VI, Dec. 1852, 202 (New Mexico and Texas).—Ib. Sitgreaves’s Report Zuñi & Colorado, 1853, 83, pl. iii. Junco caniceps, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 468, pl. lxxii, f. 1.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 201.

Sp. Char. Bill yellowish; black at the tip. Above ashy (of the same shade before and behind); the head and neck all round of this color, which extends (paling a little) along the sides, leaving the middle of the belly and crissum quite abruptly white. Lores conspicuously but not very abruptly darker. Interscapular region abruptly reddish chestnut-brown, which does not extend on the wings, and makes a triangular patch. Two outer tail-feathers entirely white; third with a long white terminal stripe on the inner web. Young streaked with blackish above and below, except along middle of belly and behind. Length, 6.00; wing, 3.23; tail, 3.04.

Hab. Rocky Mountains; from Black Hills to San Francisco Mountains, Arizona. Wahsatch and Uintah Mountains (Ridgway).

This species is similar to the common J. hyemalis in color, though paler; the tint of the under parts and sides is not quite so dark, and is less abruptly defined against the white. The conspicuous chestnut patch on the back and the dusky lores will distinguish them. The edge of the outer web of the third tail-feather is brown, not white. It differs from oregonus and cinereus in having no chestnut on the wings, especially the tertials, and from the former in the extension of the ash of the neck along the sides and much lighter head.

Young birds are streaked above and below as in other species; they may be distinguished from those of cinereus by the rufous being confined to the interscapular region, the same as in the adult.

The type skin of Junco dorsalis of Dr. Henry (see foot-note to synoptical table, p. 580) differs mainly in having the whole upper mandible entirely black, as in J. cinereus; and, as in the latter, the jugulum is pale ash, fading gradually into the white of the abdomen, instead of deep ash abruptly defined. It is very probably, as suggested by Mr. Ridgway, a hybrid with J. cinereus.

Habits. This species was first discovered and described by Dr. Woodhouse from specimens obtained by him among the San Francisco Mountains in Arizona. When procured, it was feeding in company with the Junco oregonus and various species of Parus. Its habits appeared to be very similar to those of the western Snowbird, as well as to those of the common J. hyemalis.

Dr. Coues states that he found this bird a not very common winter resident at Fort Whipple, where its times of arrival and departure, as well as its general habits, were identical with those of J. oregonus, with which it very freely associated. From this we may naturally infer that in New Mexico and Arizona it appears only as a winter visitant, and that in summer it goes elsewhere to breed. Its summer resorts, as well as our knowledge of its breeding-habits, nest, and eggs, remain to be determined, or are only imperfectly known. It evidently retires to the highlands and to mountain regions to breed, and probably has a much more extended habitat than that of which we now have any knowledge. Upon this problem Mr. Ridgway’s observations have already shed some valuable and suggestive light. He met with this bird only among the pine woods of the Wahsatch Mountains, where, however, it was a very common bird, and where it was also breeding. Its manners and notes were scarcely different from those of J. oregonus. It is, however, a shyer bird than the latter, and its song, which is only a simple trill, is rather louder than that of either the hyemalis or the oregonus.

Dr. Coues writes me that both “the Gray-head and the Oregon Snowbirds are common species about Fort Whipple in winter, arriving about the middle of October, and remaining in numbers until early in April, when they thin off, although some may usually be observed during the month, and even a part of the next. Oregonus far outnumbers caniceps. So far as I could see, their habits are precisely the same as those of the eastern Snowbird. During snow-storms they used to come familiarly about our quarters, and I once captured several of both species, enticing them into a tent in which some barley had been strewn, and having the flap fixed so that it could be pulled down with a string in a moment. They always associated together, and once, on firing into a flock, I picked up a number of each kind, and one Junco hyemalis. The latter can only be considered a straggler in this region, although I secured three specimens one winter.”

This species was very rare in Colorado, according to Mr. Aiken, in the winter of 1871-72, but became common in March, and a few remained up to the 3d of May. No females of this species were observed by him.

Mr. J. A. Allen mentions first meeting with this species at an elevation of seven thousand feet, and from that height it was common, on the slopes of Mount Lincoln, to the extreme limit of the timber line.

Genus POOSPIZA, CabanisPoospiza, Cabanis, Wiegmann’s Archiv, 1847, I, 349. (Type, Emberiza nigro-rufa, D’Orb., or Pipilo personata, Sw.)

Poospiza bilineata.

Gen. Char. Bill slender, conical, both outlines gently curved. Under jaw with the edges considerably inflected; not so high as the upper. Tarsi elongated, slender; considerably longer than the middle toe. Toes short, weak; the outer decidedly longer than the inner, but not reaching to the base of the middle claw. Hind toe about equal to the middle without its claw. All the claws compressed and moderately curved. Wings rather long, reaching about over the basal fourth of the exposed portion of the rather long tail. Tertiaries and secondaries about equal, and not much shorter than the lengthened primaries; the second to fifth about equal and longest; the first considerably shorter, and longer than the seventh. Tail long, slightly emarginate, graduated; the outer feather abruptly shorter than the others. Feathers broad, linear, and rather obliquely truncate at the ends, with the corners rounded.

Color. Uniform above, without streaks. Beneath white, with or without a black throat. Black and white stripes on the head.

We are by no means sure that the two North American specimens here indicated really belong to the genus Poospiza, but we know no better position for them. They may be distinguished as follows:—

Common Characters. Lores and beneath the eye black, a white orbital ring, white spot above the lore (in bilineata continued back in a superciliary stripe); a white maxillary stripe. Lateral tail-feathers, with outer web, and terminal border of inner, hoary or pure white.

A. Throat black in adult; sides not streaked.

A continuous white superciliary stripe1. P. bilineata. Black patch of throat covering jugulum, with a convex outline behind. Crown and back without streaks, concolored. Wing-coverts without white bands; lesser coverts ash. Wing, 2.75; tail, 2.85; bill, from nostril, .37; tarsus, .65.

No white superciliary stripe2. P. mystacalis. Black patch of throat not extending on jugulum; its posterior outline truncated. Crown and back with distinct black streaks. Back scapulars and rump rufous in contrast with the ash of head and neck. Wing-coverts with two narrow, sharply defined white bands; lesser coverts black. Wing, 2.80; tail, 3.30; bill, .40; tarsus, .80. Hab. Mexico.

B. Throat white; sides streaked.

3. P. belli. No white superciliary stripe. A dusky spot in middle of the breast. Upper parts ashy, concolored, with indistinct streaks on the back. Wings somewhat more brownish, the coverts with two indistinct light (not white) bands.

α. Wing, 2.50; tail, 2.50; bill, .31; tarsus, .74. Dorsal streaks obsolete. Hab. California … var. belli.

β. Wing, 3.20; tail, 3.20; bill, .35; tarsus, .76. Dorsal streaks distinct. Hab. Middle Province of United States. … var. nevadensis.

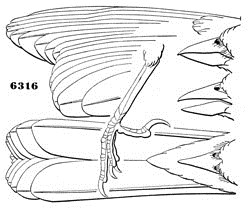

Poospiza bilineata, SclaterBLACK-THROATED SPARROWEmberiza bilineata, Cassin, Pr. A. N. Sc. Ph. V, Oct. 1850, 104, pl. iii, Texas.—Ib. Illust. I, v, 1854, 150, pl. xxiii. Poospiza bilineata, Sclater, Pr. Zoöl. Soc. 1857, 7.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 470.—Ib. Mex. Bound. II, Birds, 15.—Heerm. X, c. 14.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 203.

Poospiza bilineata.

6316

Sp. Char. Above uniform unspotted ashy-gray, tinged with light brown; purer and more plumbeous anteriorly, and on sides of head and neck. Under parts white, tinged with plumbeous on the sides, and with yellowish-brown about the thighs. A sharply defined superciliary and maxillary stripe of pure white, as also the lower eyelid, the former margined internally with black. Loral region black, passing insensibly into dark slate on the ears. Chin and throat between the white maxillary stripes black, ending on the upper part of the breast in a rounded outline. Tail black, the lateral feathers edged externally and tipped on inner web with white. Bill blue. Length, 5.40; wing, 2.75; tail, 2.90. Sexes alike.

Hab. Middle Province of United States north to 40°, between Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada. (As far west as Janos and the Mohave villages.) Matamoras (rare at San Antonio; Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 488).

This species in external form is very similar to P. belli, and will probably fall in the same genus. The cutting edges of the bill are much inflexed. The first quill is shorter than the sixth. The tail is a good deal rounded; the feathers broad.

The white maxillary stripe does not come quite to the base of the under jaw, which there is black. There is a hoary tinge on the forehead. The white superciliary stripes almost meet on the forehead.

In the immature bird the throat is white with a dusky clouding along each side; the upper part of the breast streaked with brown.

Habits. The Black-throated Sparrow, generically associated with Bell’s Finch, has several well-marked distinctive peculiarities in habits. Their eggs are also totally unlike those of the present species, being much more like those of the Peucæa and of Leucosticte griseinucha, and, like them, white and unspotted.

This species was first described by Mr. Cassin from specimens obtained in Western Texas by John W. Audubon, and its habitat was at first supposed to be restricted to the valleys of the Rio Grande and the Gila, but more recent explorations show it to have a much wider distribution. It is found from Western Texas through part of Mexico, New Mexico, the Indian Territory, and Arizona, to Southern California, and towards the north throughout the region of the Great Basin to an extent not yet fully determined. In portions at least of this territory it is migratory, and only resident in the summer months.

Mr. Dresser found this Sparrow very abundant during July and August in the mesquite thickets in the town of Matamoras. In December it was equally common at Eagle Pass, but at San Antonio it was quite a rare bird. He only observed it on two or three occasions at a rancho on the Medina River, and late in June a nest and four eggs were obtained. Between Laredo and Matamoras, after crossing the Nueces, he found these birds very numerous, and near Laredo met with several nests, some containing young and some eggs nearly hatched. One taken on the 20th of July contained three fresh eggs, probably indicating a second laying. This nest was in a low bush, carefully concealed. It was composed of straws and lined with fine roots. The eggs, when fresh, were nearly white, with a delicate bluish tinge. On his journey down the river he found many nests, all empty or containing young. Some of these were partially lined with cotton. Though not wild, the birds were so restless that he found it difficult to shoot them. Dr. Woodhouse obtained one specimen on the Rio Pedro, in Texas.

In Mexico this Sparrow was found by Lieutenant Couch to be numerous in parts of Tamaulipas, Nueva Leon, Coahuila, and other States on the Rio Grande, immediately south and west of the limits of the territory of the United States. It was first seen at Santa Rosalio, and specimens obtained, though none were noticed at Brownsville, only twenty miles east, during a month’s residence. At Charco Escondido, forty miles farther in the interior, it was very plentiful, and although it was early in March, had already reared a brood of young, one specimen appearing to be a young bird only a few weeks old. Its favorite home appeared to be the scattered mesquite, on the plains east of the Sierra Madre. During the warm hours of the day it does not seek the shade, but may always be found chirping and hopping from one bush to another. South of Cadoreita the birds disappeared, but after a month’s loss of their company he again met with them among some flowering Leguminosa, between Pesquieria and Rinconada. He thus found it several times entirely absent from districts of considerable extent, but always reappearing again throughout his journey. The usual note of this bird, at the season in which he met with it, was a simple chirp; but on one occasion, having halted during a norther in Tamaulipas, he heard a “gay little black-throated fellow,” regardless of the bitter wind, from the top of a yellow mimosa then in bloom, give utterance to a strain of sprightly and sweet notes, that would compare favorably with those of many more famed songsters.

Dr. Coues found this Sparrow very abundant in the southern and western portions of Arizona, though rare at Fort Whipple, where the locality was unsuited to it, as it seemed to prefer open plains, grassy or covered with sagebrush.

Mr. J. H. Clarke, who met with these birds in Tamaulipas, Texas, and New Mexico, speaks of them as abundant and widely distributed. He found them on the lower Rio Grande, but more abundantly in the interior, seeming to prefer the stunted and sparse vegetation of the sand-hills and dry plains to the cottonwood groves and willow thickets of the river valleys, where they were never seen. They would be very inconspicuous did not the male occasionally perch himself on some topmost branch and pour forth a continuous strain of music. In the more barren regions they were the almost exclusive representatives of the feathered tribes.

Dr. Heermann first remarked this Finch near Tucson, in Arizona, where he found it associated with other Sparrows in large flocks. They were flying from bush to bush, alighting on the ground to pick up grass-seeds and insects. They were quite numerous, and he traced them as far into Texas as the Dead Man’s Hole, between El Paso and San Antonio.

Dr. Cooper found a few of these birds on the treeless and waterless mountains that border the Colorado Valley, in pairs or in small companies, hopping along the ground, under the scanty shrubbery. In crossing the Providence Range, in May, Dr. Cooper found their nest, containing white eggs.

Both species of Poospiza, the belli and the bilineata, according to Mr. Ridgway, are entirely peculiar in their manners, habits, and notes. Both, he states, are birds characteristic of the arid artemisia plains of the Great Basin, and, with the Eremophila cornuta, are often the only birds met with on those desert wastes. The two species, he adds, are quite unlike in their habits and manners. They each have about the same extent of habitat, and even often frequent the same locality. While the P. bilineata is partial to dry sandy situations, inhabiting generally the arid mesa extending from the river valleys back to the mountains, the P. belli is almost confined to the more thrifty growth of the artemisia, as found in the damper valley portions. The P. belli is a resident species, and even through the severest winters is found in abundance. The P. bilineata is exclusively a summer bird, one of the latest to come from the South, and much the more shy of the two; its manners also are quite different.

Both birds have one common characteristic, which renders them worthy of especial remark. This is the peculiar delivery and accent, and the strange sad tone of their spring song, which, though unassuming and simple, is indeed strange in the effect it produces. This song, so plaintive and mournful, harmonizes with the dull monotony of the desert landscape.

Mr. Ridgway states that the P. bilineata is not so abundant as the other species, and is more retiring in its habits. It principally frequents the desert tracts and sandy wastes, on which are found only the most stunted forms of sage-brush. Its song, though quite simple, is exceedingly fine, its modulation being somewhat like wut´-wut´-ze-e-e-e-e-e, the first two syllables being uttered in a rich metallic tone, while the final trill is in a lower key, and of the most liquid and tremulous character imaginable. This simple chant is repeated every few seconds, the singer being perched upon a bush. He adds that this bird arrives on the Truckee Reservation about the 13th of May. The nest is built in sage-bushes, and the eggs are found from the 7th to the 21st of June. The nests are usually about one foot from the ground, or thereabouts.

The eggs vary in size from .70 by .55 of an inch to .75 by .60. They are of a rounded-oval shape, and of a pure white with a slight tinge of blue, somewhat resembling the eggs of the Bachman Finch.

Poospiza belli, SclaterBELL’S SPARROWEmberiza belli, Cassin, Pr. A. N. Sc. Phila. V, Oct. 1850, 104, pl. iv (San Diego, Cal.). Poospiza belli, Sclater, Pr. Zoöl. Soc. 1857, 7.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 470.—Heerm. X, s. p. 46. Zonotrichia belli, Elliot, Illust. Birds N. Am. I, pl. xiv.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 204.

Sp. Char. Upper parts generally, with sides of head and neck, uniform bluish-ash, tinged with yellowish-gray on the crown and back, and with a few very obsolete dusky streaks on the interscapular region. Beneath pure white, tinged with yellowish-brown on the sides and under the tail. Eyelids, short streak from the bill to above the eye, and small median spot at the base of culmen, white. A stripe on the sides of the throat and spot on the upper part of the breast, with a few streaks on the sides, with the loral space and region round the eyes, plumbeous-black. Tail-feathers black; the outer edged with white. Wing-feathers all broadly edged with brownish-yellow; the elbow-joint tinged with yellowish-green. Bill and feet blue. Length, 5.70; wing, 2.80; tail, 2.90. (Largest specimen, 6,338 ♂, Cosumnes River).

Hab. Southern California.

The colors are softer and more blended in the autumn; the young are obsoletely streaked on the breast.

Habits. Bell’s Finch has apparently a more restricted distribution than the Black-throated species, and is resident wherever found. It has been met with at Posa Creek, Cal., by Dr. Heermann, at Fort Thorn by Dr. T. C. Henry, and along the Colorado River by Drs. Kennerly and Möllhausen. It has likewise been found in Southern California, as far north as Sacramento Valley, and in the valley of the Gila.

Dr. Cooper states that all the extensive thickets throughout the southern half of California are the favorite resorts of this bird. There they apparently live upon small seeds and insects, indifferent as to water, or depending upon what they obtain from dews or fogs. They reside all the year in the same localities, and were also numerous on the island of San Nicolas, eighty miles from the mainland. In spring the males utter, as Dr. Cooper says, a low monotonous ditty, from the top of some favorite shrub, answering each other from long distances. Their nest he found about three feet from the ground, composed of grasses and slender weeds, lined with hair and other substances. The eggs, four in number, he describes as pale greenish, thickly sprinkled over with reddish-brown dots. At San Diego he found the young hatched out by May 18, but thinks they are sometimes earlier. It is also a common bird in the chaparral of Santa Clara Valley, and also, according to Dr. Heermann, along the Cosumnes River.

In Arizona, according to Dr. Coues, it is rather uncommon about Fort Whipple, owing to the unsuitable nature of the locality, but is abundant among the sage-brush of the Gila Valley, where it keeps much on the ground, and where its movements are very much like those of a Pipilo.

Drs. Kennerly and Möllhausen met with these Sparrows on the Little Colorado River, in California, December 15. They were found during that month along the banks of the river wherever the weeds and bushes were thick. It was never observed very far from the water, and its food, at that season, seemed to consist of the seeds of various kinds of weeds. Its motions were quick, and, when started up, its flight was short, rapid, and near the earth.

Dr. Heermann states that in the fall of 1851 he found this species in the mountains bordering the Cosumnes River, and afterwards on the broad tract of arid land between Kerr River and the Tejon Pass, and again on the desert between that and the Mohave River. He often found them wandering to a great distance from water. With only a few exceptions, these were the only birds inhabiting the desolate plains, where the artemisia is the almost exclusive vegetation. When undisturbed, it chants merrily from some bush-top, but, at the approach of danger, drops at once to the ground and disappears in the shrubbery or weeds. Its nest he found built in a bush, composed of twigs and grasses, and lined with hair. The eggs, four in number, he describes as of a light greenish-blue, marked with reddish-purple spots, differing in intensity of shade.

Poospiza belli, var. nevadensis, RidgwayARTEMISIA SPARROWPoospiza belli, var. nevadensis, Ridgway, Report on Birds of 40th Parallel.

Sp. Char. Resembling P. belli, but purer ashy above, with the dorsal streaks very distinct, instead of almost obsolete. Wing, 3.20 (instead of 2.50); tail, 3.20 (instead of 2.50); bill (from forehead), .35; tarsus, .76. (Type, No. 53,516 ♂, Western Humboldt Mountains, Nev., United States Geol. Expl. 40th Par.)

Young. Streaked above, the crown obsoletely, the back distinctly. Whole breast and sides with numerous short dusky streaks upon a white ground. Markings about the head indistinct, wing-bands more distinct than in the adult.